{{mi| {{expert needed|date=April 2016}} {{overly detailed|date=April 2016}} }}

Fort Ross | |

| |

| Location | Fort Ross State Historic Park, Sonoma County, California, USA |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Healdsburg, California |

| Coordinates | 38°30′51.44″N 123°14′33.75″W / 38.5142889°N 123.2427083°W |

| Built | 1812 |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000239 |

| CHISL No. | 5 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 [2] |

| Designated NHL | November 5, 1961 [3] |

| Designated CHISL | 1932 [1] |

Fort Ross ( Russian: Форт-Росс), originally Fortress Ross (Крѣпость Россъ, tr. Krepostʹ Ross), is a former Russian establishment on the west coast of North America in what is now Sonoma County, California, in the United States. It was the hub of the southernmost Russian settlements in North America from 1812 to 1864. It has been the subject of archaeological investigation and is a California Historical Landmark, a National Historic Landmark, and on the National Register of Historic Places. It is part of California's Fort Ross State Historic Park.

History

Beginning with Columbus in 1492, the Spanish presence in the Western hemisphere, (like most other European exploration and colonization) traveled west across the Atlantic Ocean, then around or across the Americas to reach the Pacific Ocean. The Russian expansion, however, moved east across Siberia and the northern Pacific. In the early nineteenth century, Spanish and Russian expansion met along the coast of Spanish Alta California, with Russia pushing south and Spain pushing north. By that time, British and American fur trade companies had also established a coastal presence, in the Pacific Northwest, and Mexico was soon to gain independence. Mexico ceded Alta California to the United States of America following the Mexican-American War (1848). The history of the Russian Fort Ross settlement began during Spanish rule and ended under Mexico.

Russian-American Company

| “ | This settlement [Ross] has been organized through the initiative of the Company. Its purpose is to establish a [Russian] settlement there or in some other place not occupied by Europeans, and to introduce agriculture there by planting hemp, flax and all manner of garden produce; they also wish to introduce livestock breeding in the outlying areas, both horses and cattle, hoping that the favorable climate, which is almost identical to the rest of California, and the friendly reception on the part of the indigenous people, will assist in its success. | ” |

| — From an 1813 report to Emperor Alexander from the Russian American Company Council, concerning trade with California and the establishment of Fort Ross [4] | ||

Russian personnel from the Alaskan colonies initially arrived in California aboard American ships. In 1803, American ship captains already involved in the sea otter maritime fur trade in California proposed several joint venture hunting expeditions to Alexander Andreyevich Baranov, on half shares using Russian supervisors and native Alaskan hunters to hunt fur seals and otters along the Alta and Baja Californian coast. Subsequent reports by the Russian hunting parties of uncolonized stretches of coast encouraged Baranov, the Chief Administrator of the Russian-American Company (RAC), to consider a settlement in California north of the limit of Spanish occupation in San Francisco. In 1806 the Russian Ambassador to Japan, and RAC director Nikolay Rezanov, undertook an exploratory trade mission to California to establish a formal means of procuring food supplies in exchange for Russian goods in San Francisco. While guests of the Spanish, Rezanov's captain, Lt. Khvostov, explored and charted the coast north of San Francisco Bay and found it completely unoccupied by other European powers. Upon his return to New Archangel, Rezanov recommended to Baranov, and Emperor Aleksandr I, that a settlement be established in California. [4]

Fort Ross was established by Commerce Counselor Ivan Kuskov of the Russian-American Company. [5] [6]: 83–84 In 1808 Baranov sent two ships, the Kad'yak and the Sv. Nikolai, on an expedition south to establish settlements for the RAC with instructions to bury "secret signs"(possession plaques). Kuskov, on the Kad'yak, was instructed to bury the plaques, with an appropriate possession ceremony, at Trinidad, Bodega Bay, and the north shore of San Francisco, indicating Russian claims to the land. After sailing into Bodega Bay in 1809 on the Kad'yak and returning to Novoarkhangelsk with beaver skins and 1,160 otter pelts, Baranov ordered Kuskov to return and establish an agricultural settlement in the area. After a failed attempt in 1811, Kuskov sailed the brig Chirikov back to Bodega Bay in March 1812, naming it the Gulf of Rumyantsev or Rumyantsev Bay (залив Румянцева, Zaliv Rumyantseva) in honor of the Russian Minister of Commerce Count Nikolai Petrovich Rumyantzev. [7] He also named the Russian River the Slav (Славянка, Slavyanka). On his return, Kuskov found American otter hunting ships and otter now scarce in Bodega Bay. After exploring the area they ended up selecting a place 15 miles (24 km) north that the native Kashaya Pomo people called Mad shui nui or Metini. Metini, the seasonal home of the native Kashaya Pomo people, had a modest anchorage and abundant natural resources and would become the Russian settlement of Fortress Ross.

The present name of Fort Ross [8] appears first on a French chart published in 1842 by Eugene Duflot de Mofras, who visited California in 1840. [9] The name of the fort is said to derive from the Russian word rus or ros, the same root as the word "Russia" (Pоссия, Rossiya) [10] and not from Scottish " Ross". According to William Bright, "Ross" is a poetic name for a Russian in the Russian language. [11]

Fort Ross was established as an agricultural base from which the northern settlements could be supplied with food and carry on trade with Alta California. [4] Yet during its initial ten years of operations the post "provided the company with nothing but heavy expenses for its maintenance." [12] Fort Ross itself was the hub of a number of smaller Russian settlements comprising what was called "Fortress Ross" on official documents and charts produced by the Company itself. [13] Colony Ross referred to the entire area where Russians had settled. [13] These settlements constituted the southernmost Russian colony in North America and were spread over an area stretching from Point Arena to Tomales Bay. [9] The colony included a port at Bodega Bay called Port Rumyantsev (порт Румянцев), a sealing station on the Farallon Islands 18 miles (29 km) out to sea from San Francisco, and by 1830 three small farming communities called "ranchos" (Ранчо): Chernykh (Ранчо Егора Черных, Rancho Egora Chernykh) near present-day Graton, Khlebnikov (Ранчо Василия Хлебникова, Rancho Vasiliya Khlebnikova) a mile north of the present day town of Bodega in the Salmon Creek valley, and Kostromitinov (Ранчо Петра Костромитинова, Rancho Petra Kostromitinova) [9] on the Russian River.

Local enterprise

In addition to farming and manufacturing, the Company carried on its fur-trading business at Fort Ross, but by 1817, after 20 years of intense hunting by Spanish, American and British ships - followed by Russian efforts - had practically eliminated sea otter in the area. [14]

Fort Ross was the site of California's first windmills and shipbuilding. Russian scientists associated with the colony were among the first to record California's cultural and natural history. [15] The Russian managers introduced many European innovations such as glass windows, stoves, and all-wood housing into Alta California. Together with the surrounding settlement, Fort Ross was home to Russians (during the 19th and early 20th century Russian subjects included Poles, Finns, Ukrainians, Estonians, and numerous other nationalities and ethnic groups of the Russian Empire [16]), as well as North Pacific Natives, Aleuts, Kashaya ( Pomo), and Creoles. The native populations of the Sonoma and Napa County regions were affected by smallpox, measles and other European diseases, one instance that can be traced to the settlement of Fort Ross. However, the first vaccination in California history was carried out by the crew of the Kutuzov, a Russian-American Company vessel arriving from Callao, Peru which brought vaccine to Monterey in August,1821. The Kutuzov's surgeon vaccinated 54 persons. Another instance of disease prevention was when a visiting Hudson's Bay Company hunting party was refused entry to the Colony in 1833, when it was feared that a malaria epidemic which had devastated the Central Valley was carried by its members.

An 1841 inventory for Mr. Sutter describes the settlement surrounding the fort: "thirty-five planked dwellings with glazed windows, a floor and a ceiling; each had a garden. There were eight sheds, eight bathhouses and ten kitchens."

By 1841 the settlement's agricultural importance had increased considerably, though the local population of fur-bearing marine mammals had been long depleted by international over-hunting, the hostilities between British Canada and Russian America made Fort Ross one of the most important Russian strongholds in America

20th century

State Route 1 once bisected Fort Ross. It entered from the northeast where the Kuskov House once stood, and exited through the main gate to the southwest. The road was eventually diverted, and the parts of the fort that had been demolished for the road were rebuilt. The old roadway can still be seen going from the main gate to the northwest; the rest (within the fort and extending northeast) has been removed.

The Fort Ross Chapel collapsed in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake but much of the original structural woodwork remained and it was re-erected in 1916, but retained the appearance of the American ranch-period modifications when it was used as a stable. [17] Several other restorations ensued, but none incorporated the information in Voznesensky's 1841 water-colour which portray the chapel with copper-clad cupola and tower, and red-metal roof. [17] "The Fort Ross Chapel was found eligible for designation as a National Historic Landmark in 1969, architecturally significant as a rare U.S. example of a log church constructed on a Russian quadrilateral plan. An accidental fire destroyed the chapel on October 5, 1970. This loss of the original workmanship and materials of the chapel led to withdrawal of the Chapel's Landmark designation in 1971. A complete reconstruction of the chapel was undertaken in 1973 and the Fort Ross settlement, as a whole, retains its National Historic Landmark designation." [18] The current chapel was built during the intensive restoration activity that followed, but retains the American ranch period appearance.

A few months later the roof of the Rotchev House was damaged by fire.

The Russian cemetery containing at least 270 burials [ citation needed]on an adjacent ridge has been cleared and the gravesites identified by archaeological excavations during 1990-1992. A large orchard, including several original trees planted by the Russians, is located inland on Fort Ross Road in Sonoma County. [19]

Fort Ross is now a part of Fort Ross State Historic Park, open to the public. [20]

Windmills at Fort Ross

Much archaeological research has been done at Fort Ross, more recently in search of the windmills. The historical record states there were at least three windmills, possibly four, although the fourth may have been a watermill or a man or animal powered mill. [21] The windmills have gained much attention because various accounts of their exact locations are sometimes inconsistent and vague. There was, in fact, one windmill located not far from the northern end of the blockade, which was most likely used to grind wheat and barley flour. [21] Based on the descriptions given by people who visited Fort Ross, it has been concluded that the main windmill, located outside the blockade, was the traditional style Russian stolbovki. [21] The root word "stolb" means thick vertical pole.

At the time, the only mills in California, which was under Spanish/Mexican rule, were either water or animal powered. [22] What made the Russian mills significant is that they were the first windmills in California. The Russian stolbovki needed a very large center post which was sunk into the ground and supported the transverse pole. The transverse pole was rotated by the wings of the mill that faced the wind current. [22] Archaeologists are searching for the remains of this center post, which would have left a significant indentation in the ground.

In October 2012 a modern interpretation of one of Fort Ross' windmills was erected and placed near the parking lot and visitors center of the State Historic Park. The windmill was built completely by hand, using the same methods that were presumed to have been used in the days of the Russian American settlement. Its pieces were constructed in Russia and shipped to California, where it was fully assembled and now stands as the only working Russian windmill of this style. It has been pointed out, however, that this is a replica of a 19th or early 20th century Vologda Province windmill, and only bears a slight resemblance to the windmill recorded at Fort Ross in 1841 by Ilya Voznesensky. In Voznesensky's painting the roof is hipped rather than peaked, and there is no roofed exterior porch on the upper left-hand side. The supporting cribbing is covered in the 1841 rendition, and the proportions are noticeably different. The placement near the parking lot at Fort Ross also conflicts with archeologists' views of the actual site of the windmill as portrayed by Voznesensky.

Colonial administrators

Fort Ross colony had five administrators:

- Ivan A. Kuskov, 1812–1821

- Karl J. von Schmidt, 1821–1824

- Pavel I. Shelikhov, 1824–1830

- Petr S. Kostromitinov, 1830–1838

- Aleksander G. Rotchev, 1838–1841

Derived place names

Along with its status as a National Historic Landmark, the fort itself and the surrounding area are part of Fort Ross State Historic Park. Fort Ross also designates the small rural community that exists between the towns of Cazadero, Jenner, and Gualala, with the Fort Ross Elementary School at its center. [13]

Milestones

16th and 17th centuries

- 1542–1543: Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo visits San Diego, Farallon Islands, Cape Mendocino, Cape Blanco.

- 1579–1639: Russian frontiersmen penetrate eastward to Siberia and the Pacific.

- 1602: S. Viscaino explores to the Columbia River region, naming the Farallon Islands, Point Reyes and the Rio Sebastian (present-day Russian River).

18th century

- 1728: Vitus Bering and Alexei Chirikov explore Bering Strait.

- 1741–1742: Bering and Chirikov claim Russian America (Alaska) for Russia.

- 1769: Gaspar de Portola traveling overland discovers San Francisco Bay.

- 1775: Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra anchors in outer Bodega Bay, trades with the local Indians.

- 1784: Russians Grigoriy Shelikhov and his wife Nataliya establish a base on Kodiak Island.

- 1799: Russian American Company (with manager Aleksandr Baranov) establishes Novo Arkhangelsk (New Archangel, now Sitka, Alaska).

19th century

- 1806: Count Nikolai Rezanov, Imperial Ambassador to Japan and director of the Russian American Company, visits the Presidio of San Francisco.

- 1806–1813: American ships bring Russians and Alaska Natives on 12 California fur hunts.

- 1808–1811: Ivan Kuskov lands in Bodega Bay (Port Rumiantsev), builds structures and hunts in the region.

- 1812, March 15: Ivan Kuskov with 25 Russians and 80 Native Alaskans arrives at Port Rumiantsev and proceeds north to establish Fortress Ross.

- 1812, September 11: The Fortress is dedicated on the name-day of Emperor Aleksandr I

- 1816: Russian exploring expedition led by Captain Otto von Kotzebue visits California with naturalists Adelbert von Chamisso, Johann Friedrich von Eschscholtz, and artist Louis Choris.

- 1817: Russian Chief Administrator Captain Leonty Gagemeister conducts treaty with local tribal chiefs for possession of property near Fortress Ross. First such treaty conducted with native peoples in California.

- 1818: The Rumiantsev, first of four ships built at Fortress Ross. The Buldakov, Volga and Kiakhta follow, as well as several longboats.

- 1821: Russian Imperial decree gives Native Alaskans and Creoles civil rights protected by law

- 1836: Fr. Veniaminov (St. Innocent) visits Fort Ross, conducts services, and carries out census.

- 1841: Rotchev sells Fort Ross and accompanying land to John Sutter.

20th and 21st centuries

- 1903: California Landmarks League purchases the 2.5-acre (1 ha) fort property from George W. Call for $3000.

- 1906: The fort is deeded to what becomes the California State Parks Commission.

- 1906, April 18: California's major historical earthquake causes considerable damage to the buildings of the fort compound.

- 1916: Fort Ross is partially restored.

- 1970: Fires at Fort Ross destroy the chapel and damage the roof of the Rotchev House.

- 1971: Fort Ross is once again only partially restored.

- 1974: Restored Fort Ross officially reopened. [23]

- 2010: The Rotchev House is opened as a house museum

- 2010: Memorandum of Agreement signed in San Francisco between the State of California and Renova Group, a Russian entrepreneurial company, whereby the Russian company undertakes to fund the continuing upkeep and operation of Fort Ross.

- 2012, March 15: Bodega Bay (Port Rumiantsev) celebrates its 200th anniversary as the main port of Russian California.

- 2012, April: The Russian River at Jenner celebrates its 200th anniversary of being named Slavyanka by Ivan Kuskov

- 2012, August: an American delegation attends Tot'ma, Russia's 875th anniversary and 200th anniversary of Fort Ross' founding by Ivan Kuskov, a Tot'ma native.

- 2012: Fort Ross State Historic Park celebrated is 200 year bicentennial of the Russian settlement in a historic two-day event that was attended by over 6,500 people.

- 2012, September: The Kashaya expedition to Russia. An unofficial delegation from California was hosted in Russia marking the Kashaya's first ever trip to Russia. [24]

- 2012, October: A working interpretation of the original windmill was built and dedicated at the park.

Buildings

|

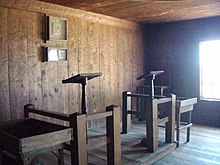

Kuskov House, located in the mid-eastern area of the fort, was the residence of Ivan Kuskov and the other managers up to Alexander Rotchev. | ||

|

Rotchev House, located in the northwest area of the fort, was where Alexander Rotchev, the last manager of Fort Ross, lived with his family. Built circa 1836, it is the only remaining original building. | ||

|

Officials' Quarters, located in the mid-western area of the fort near the gate. | ||

| |||

| |||

California State Landmark

On June 1, 1932, Fort Ross was designated "California Historical Landmark #5".

Climate

The National Weather Service has maintained a cooperative weather station at Fort Ross for many years.[ citation needed] Based on those observations, Fort Ross has cool, damp weather most of the year. Fog and low overcast is common throughout the year. There are occasional warm days in the summer, which also tend to be relatively dry except for drizzle from heavy fogs or passing showers. According to the Köppen climate classification system, Fort Ross has a warm-summer Mediterranean climate (Csb).

In January, average temperatures range from 57.0 °F (13.9 °C) to 41.5 °F (5.3 °C). In July, average temperatures range from 66.3 °F (19.1 °C) to 47.8 °F (8.8 °C). September is actually the warmest month with average temperatures ranging from 68.1 °F (20.1 °C) to 48.7 °F (9.3 °C). There are an average of only 0.2 days with highs of 90 °F (32 °C) or higher and 5.8 days with lows of 32 °F (0 °C) or lower. The record high temperature was 97 °F (36 °C) on September 3, 1950. The record low temperature was 20 °F (−7 °C) on December 8, 1972.

Average annual precipitation is 37.64 inches (956 mm), falling on an average of 81 days each year. The wettest year was 1983 with 71.27 inches (1.810 m) and the driest year was 1976 with 17.98 inches (457 mm). The wettest month on record was February 1998 with 21.68 inches (551 mm). The most rainfall in 24 hours was 5.70 inches (145 mm) on January 14, 1956. Snow rarely falls at Fort Ross; the record snowfall was 0.4-inch (10 mm) on December 30, 1987. [26]

| Climate data for Fort Ross | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 83 (28) |

79 (26) |

78 (26) |

86 (30) |

94 (34) |

88 (31) |

88 (31) |

87 (31) |

97 (36) |

97 (36) |

80 (27) |

76 (24) |

97 (36) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 56.8 (13.8) |

58.3 (14.6) |

59.2 (15.1) |

60.9 (16.1) |

62.9 (17.2) |

65.7 (18.7) |

66.5 (19.2) |

67.1 (19.5) |

68 (20) |

66.1 (18.9) |

61.5 (16.4) |

57.5 (14.2) |

62.6 (17.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 41.7 (5.4) |

42.4 (5.8) |

42.3 (5.7) |

42.6 (5.9) |

44.6 (7.0) |

47 (8) |

48 (9) |

48.9 (9.4) |

49 (9) |

47.3 (8.5) |

44.6 (7.0) |

41.7 (5.4) |

45 (7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 22 (−6) |

25 (−4) |

26 (−3) |

26 (−3) |

30 (−1) |

34 (1) |

35 (2) |

30 (−1) |

34 (1) |

30 (−1) |

27 (−3) |

20 (−7) |

20 (−7) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 8.48 (215) |

6.81 (173) |

5.38 (137) |

2.72 (69) |

1.39 (35) |

0.58 (15) |

0.08 (2.0) |

0.15 (3.8) |

0.63 (16) |

2.39 (61) |

5.17 (131) |

6.83 (173) |

40.62 (1,032) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

| Average precipitation days | 13 | 12 | 11 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 12 | 79 |

| Source: [27] | |||||||||||||

Popular culture

Fort Ross serves as the backdrop in the short story " Facts Relating to the Arrest of Dr. Kalugin," part of Kage Baker's series of science fiction stories concerning " The Company."

In Adrienne Jones's historical novel, Another Place, Another Spring, set in 19th century Russia, a young countess and her maid, sentenced to live in exile in Siberia get help to escape to Fort Ross in California.

See also

| Part of a series on |

|

European colonization of the Americas |

|---|

|

|

|

Notes

- ^ "Fort Ross". Office of Historic Preservation, California State Parks. Retrieved 2012-10-15.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- ^ "Fort Ross". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2007-11-14. Retrieved 2008-06-17.

- ^ a b c The Russian American Colonies

- ^ The Destiny of Russian America

- ^ Khlebnikov, K.T., 1973, Baranov, Chief Manager of the Russian Colonies in America, Kingston: The Limestone Press, ISBN 0919642500

- ^ Hubert Howe Bancroft; Alfred Bates; Ivan Petroff; William Nemos (1887). History of Alaska: 1730-1885. San Francisco, California: A. L. Bancroft & company. p. 482. Retrieved Jan 10, 2010.

- ^ Thompson, R. A. (1896). The Russian Settlement in California Known as Fort Ross, Founded 1812...Abandoned 1841: Why They Came and Why They Left. Santa Rosa, California: Sonoma Democrat Publishing Company. p. 3. ISBN 0-559-89342-6. Retrieved Jan 9, 2010.

- ^ a b c Historical Atlas of California

- ^ Thompson, Robert A. (1896). The Russian settlement in California known as Fort Ross, founded 1812, abandoned 1841: why the Russians came and why they left. Western Americana, frontier history of the trans-Mississippi West, 1550-1900. Vol. 5369. Sonoma Democrat Publishing Company. p. 5.

- ^ Bright, William; Erwin G. Gudde (1998). 1500 California Place Names: Their Origin and Meaning. University of California Press. p. 57. ISBN 0-520-21271-1.

- ^ Tikhmenev, P. A. A History of the Russia-American Company. ed. Richard A. Pierce and Alton S. Donnelly. Seattle: University of Washington Press. 1978, p. 141.

- ^ a b c Fort Ross and the Sonoma Coast

- ^ Suzanne Stewart; Adrian Praetzellis (November 2003). Archeological Research Issues for the Point Reyes National Seashore - Golden Gate National Recreation Area (PDF) (Report). Anthropological Studies Center, Sonoma State University. p. 335. Retrieved Jan 10, 2010.

- ^ Fort Ross Interpretive Association

- ^ Pierce

- ^ a b The American Interpretation of the Russian Colony at Fort Ross (1999)

- ^ http://www.nps.gov/nhl/DOE_dedesignations/Ross.htm

-

^

https://web.archive.org/web/20100713005230/http://www.fortrossinterpretive.org/orchard.php. Archived from

the original on July 13, 2010. Retrieved April 1, 2010.

{{ cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=( help) - ^ "Fort Ross State Historic Park Russian Colony". California State Parks. Retrieved 2011-12-09.

- ^ a b c Oleksy, Victoria (2001). Where Have All the Windmills Gone? An Archaeological Study of the Locations of the Windmills and Threshing Floors at Fort Ross, California. California: Saint Mary's College.

- ^ a b Farris, Glen (2000). The Russian Windmills of Fort Ross.

- ^ "The Navy of the Russian Empire", St. Petersburg, 1996, pg.207

- ^ http://www.pressdemocrat.com/article/20120907/ARTICLES/120909712?p=1&tc=pg

- ^ http://orthodoxwiki.org/Holy_Trinity_Chapel_%28Fort_Ross,_California%29

- ^ Weather Regional Climate Center website

- ^ "FT ROSS, CALIFORNIA (043191)". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

References

- Alekseev, A.I. (1990). The Destiny of Russian America 1741-1867. Fairbanks, Alaska: The Limestone Press. ISBN 0-919642-13-6.

- Dmytryshin, Basil; Crownhart-Vaughan, E.A.P.; Vaughan, Thomas (1989). The Russian American Colonies 1789-1867. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-87595-147-3.

- Hayes, Derek (2007). Historical Atlas of California. Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, Berkeley. ISBN 978-0-520-25258-5.

- Pierce, Richard (1984). The Russian-American Company: Correspondence of the Governors, Communications Sent:1818. Fairbanks, Alaska: The Limestone Press. ISBN 0-919642-02-0.

- Fort Ross Interpretive Association (2001). Fort Ross. Fort Ross, CA: Fort Ross Interpretive Association. ISBN 1-56540-355-X.

- Kalani, Lyn; Sweedler, Sarah (2004). Fort Ross and the Sonoma Coast. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-2896-0.

- Nordlander, David J. (1994). For God & Tsar: A Brief History of Russian America 1741–1867. Alaska Natural History Association, Anchorage, AK. ISBN 0-930931-15-7.

- Pierce, Richard (1990). Russian America: A Biographical Dictionary. Fairbanks, Alaska: The Limestone Press. ISBN 0-919642-45-4.

- Middleton, John (1999). Русская Америка 1799–1867: The American Interpretation of the Russian Colony at Fort Ross. Российская Академия Наук, Москва. ISBN 5-201-00533-0.

- Silliman, Stephen (2004). Lost Laborers in Colonial California, Native Americans and the Archaeology of Rancho Petaluma. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0-8165-2381-9.

- Hurtado, Albert (2006). John Sutter:a life on the North American frontier. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3772-X.

- Osborn, Sannie (1997). Death in the Daily Life of the Ross Colony: Mortuary Behavior in Frontier Russian America. A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, August 1997.

External links

- Renova Fort Ross Foundation

- Official Fort Ross Conservacy website

- Official Fort Ross Park docents website

- Official California State Parks website

- Fort Ross Interpretive Association Home Page

- Withdrawal of Fort Ross Chapel: National Historic Landmarks Program

Ross

Category:Colonial United States (Russian)

Category:Russian-American Company

Ross

Category:Archaeological sites in California

Category:Buildings and structures in Sonoma County, California

Ross

Category:Fur trade

Category:History of Sonoma County, California

Ross

Category:National Historic Landmarks in the San Francisco Bay Area

Category:National Register of Historic Places in Sonoma County, California

Category:Populated places established in 1812

Category:1812 establishments in Russia

Category:Former Russian colonies

Category:Russian Empire

Category:Military facilities in the San Francisco Bay Area

Category:Military history of California

Category:Russian-American history

Category:Russian-American culture in California

Category:Colonial architecture in California

Category:Articles containing video clips

Category:Populated coastal places in California