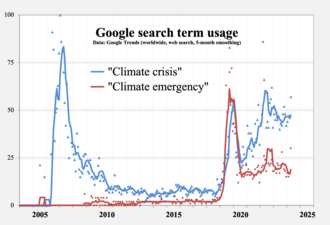

Climate crisis or climate emergency are prominent terms used to describe the threat posed by the impacts of global warming and climate change to humankind and the biosphere. Their history dates to 1980s, and a now-defunct group called Climate Crisis Coalition was founded in 2004, but these terms remained poorly known until the late 2010s, when "climate emergency" was declared the top word of 2019 by Oxford Dictionaries, who estimated that its usage rose by 10,796% over that year. [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] Examples of this shift include the "Climate Emergency Plan" presented by the Club of Rome in 2018, [7], UN Secretary General António Guterres invoking "climate crisis" in a September 2018 speech, [8] and over 1,000 jurisdictions in 19 countries making a climate emergency declaration by September of 2019. [9] In November 2019, World Scientists’ Warning of a Climate Emergency was published in the journal BioScience, where it was endorsed by over 11,000 scientists worldwide. It stated that "the climate crisis has arrived" and that an "immense increase of scale in endeavors to conserve our biosphere is needed to avoid untold suffering due to the climate crisis." [10] [11]

The term is used to describe the present situation and draw attention to the way it would continue to worsen without aggressive climate change mitigation. Those who have adopted the term crisis "believe it evokes the gravity of the threats the planet faces from continued greenhouse gas emissions and can help spur the kind of political willpower that has long been missing from climate advocacy". [2] They believe that, much as "global warming" drew out more emotional engagement and support for action than "climate change", [2] [12] [13] calling climate change a crisis could have an even stronger impact. [2]

Research has shown that what a phenomenon is called, or how it is framed, "has a tremendous effect on how audiences come to perceive that phenomenon" [14] and "can have a profound impact on the audience’s reaction". [8] The term climate crisis was found to invoke a strong emotional response in conveying a sense of urgency. [15] However, some caution that this response may be counter-productive, [16] and may cause a backlash effect due to perceptions of alarmist exaggeration. [14] [17]

The language of climate crisis and climate emergency is frequently conflated with a hypothetical societal collapse or human extinction caused by climate change. However, these outcomes remain unsupported by science and are rarely endorsed even by the scientists who have adopted the crisis terminology. [18] [19] [20]

Definitions

In the context of climate change, Pierre Mukheibir, Professor of Water Futures at the University of Technology Sydney, states that the term crisis is "a crucial or decisive point or situation that could lead to a tipping point," one involving an "unprecedented circumstance." [5] A dictionary definition states that "crisis" in this context means "a turning point or a condition of instability or danger," and implies that "action needs to be taken now or else the consequences will be disastrous." [21] Another definition differentiates the term from global warming and climate change and defines climate crisis as "the various negative effects that unmitigated climate change is causing or threatening to cause on our planet, especially where these effects have a direct impact on humanity." [17]

In November 2019, World Scientists’ Warning of a Climate Emergency argued that describing global warming as a climate emergency or climate crisis was appropriate, [22], as the sustained increases in livestock populations for meat production, tree cover loss, fossil fuel consumption, air transport, and CO2 emissions were concurrent with upward trends in climate impacts such as rising temperatures, global ice melt, and extreme weather, and these "profoundly troubling signs" in turn threaten indirect impacts such as large-scale migration and food insecurity. Its authors stated that an "immense increase of scale in endeavor" is needed to reverse these trends and conserve the biosphere, and this statement was co-signed by over 11,000 scientists. [10]

Tipping points in the climate system are often used as an additional evidence of climate crisis, [23], due to their potential for major and effectively irreversible impacts on the planet, as well as the risk of multiple tipping points getting triggered at current or near-future levels of warming. [24] [25] [26] In November 2019, prominent tipping points experts like Katherine Richardson Christensen, Will Steffen, Stefan Rahmstorf, Johan Rockström, Timothy Lenton and Hans Joachim Schellnhuber authored an article in Nature where they defined emergency as a product of risk and urgency, with urgency itself composed of reaction time divided by intervention time. They argued that since the only workable intervention is carbon neutrality, this means that the intervention time is at least 30 years (assuming the goal of global net zero by 2050), while the reaction time of some tipping points is either at zero already or is likely to be shorter than those 30 years. Consequently, they collectively stated that "we are in a state of planetary emergency", where the humanity might have already lost control of some tipping points, but urgent action to limit emissions and the resultant warming would still limit their damage and reduce the risk other tipping points being triggered in a cascade due to greater warming. [27]

In a 2021 update to the World Scientists' Warning to Humanity, [11] scientists reported that evidence of nearing or crossed tipping points of critical elements of the Earth system is accumulating, that 1990 jurisdictions have formally recognized a state of climate emergency, that frequent and accessible updates on the climate crisis or climate emergency are needed, that COVID-19 " green recovery" has been insufficient and that root-cause system changes above politics are required. [28] A 2022 update – in the form of a study document available on the Web and reported on by several text-based online news media – concluded that "We are now at ' code red' on planet Earth", warning citizens and world leaders to take necessary actions with information about tracked "recent climate-related disasters, assess[ed] planetary vital signs, and [...] [few broadly outlined] policy recommendations". [29] [30] And in September 2021, more than 200 scholarly medical journals published a call for emergency action to deal with the "environmental crisis", by which they defined global warming in excess of 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) and the destruction of ecosystems through other human activities. [31]

Use of the term

Political

Former U.S. Vice President Al Gore has used crisis terminology since the 1980s, with the term being formalized by the Climate Crisis Coalition (formed in 2004). [2]

A 1990 report from the American University International Law Review includes selected materials that repeatedly use the term "crisis". [3] Included in that report, "The Cairo Compact: Toward a Concerted World-Wide Response to the Climate Crisis" (December 21, 1989) states that "All nations... will have to cooperate on an unprecedented scale. They will have to make difficult commitments without delay to address this crisis." [3]

In September 2018, UN Secretary General António Guterres had first used the term "climate crisis" alongside other emphatic language during his address at the Climate Action Summit. [8] Guterres continued to use strong language to refer to climate change afterwards, describing the status quo policy on climate change as "suicide" in a 2019 interview. [33]. When the first part of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report was published in August 2021, he referred to it as "code red for humanity", while noting that "If we combine forces now, we can avert climate catastrophe." In February 2022, he had described the second part of the report as "an atlas of human suffering". [34] When the third report was published, he had described it as "a file of shame, cataloguing the empty pledges that put us firmly on track towards an unliveable world." [35]

In late 2018, the United States House of Representatives established the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis, a term that a journalist wrote in The Atlantic is "a reminder of how much energy politics have changed in the last decade". [36] The original House climate committee (formed in 2007) had been called the Select Committee on Energy Independence and Global Warming, [2] and was abolished when Republicans regained control of the House in 2011. [4] During the 2020 Democratic Party presidential primaries, multiple candidates have referred to "climate chaos" or "climate ruin". [37] Following the election of Joe Biden, there has been pressure on him to officially declare a climate emergency from activist groups like League of Conservation Voters and progressive lawmakers, including Senators Jeff Merkley, Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren and Sheldon Whitehouse. This would have unlocked emergency powers and funding, but there were concerns that these instruments are not appropriate for dealing with climate change. [38] As of 2023, President Biden has not made an official declaration.

In July 2019, small island states at the 5th Pacific Islands Development Forum signed The Nadi Bay Declaration on the Climate Change Crisis in the Pacific. It welcomed the then-upcoming Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C and called for global action to meet its goals, such as for coal mining to be phased out in a decade, with an immediate end to new coal projects. It also condemned the use of carryover carbon credits, which was widely considered to be an attack on the policies of Morrison government of Australia. [39] [40] In a September 2020 presentation to the United Nations, Fiji Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama described the present situation as an "environmental armageddon". [41]

In March 2019, the opposition UK Labour Party had formally declared national "environment and climate emergency" [42]; this was followed by a Parliament vote where the majority of all MPs had also voted to declare a climate emergency. [43] This made the UK the first country to make a climate emergency declaration, and they were soon followed by others. By September 2019, over 1,000 jurisdictions in 19 countries have made a climate emergency declaration. [9] By 2021, this has increased to 1,990. [11]

In June 2019, Pope Francis had officially declared climate emergency. He said that climate change threatens the future of the human family and that action must be taken to protect future generations and the world's poorest who will suffer the most from humanity's actions. [44]

Media

English-language

Call It a Climate Crisis—

and Cover It Like One

The words that reporters and anchors use matter. What they call something shapes how millions see it—and influences how nations act. And today, we need to act boldly and quickly. With scientists warning of global catastrophe unless we slash emissions by 2030, the stakes have never been higher, and the role of news media never more critical.

We are urging you to call the dangerous overheating of our planet, and the lack of action to stop it, what it is—a crisis––and to cover it like one.

Public Citizen open letter

June 6, 2019

[45]

Following a September 2018 usage of "climate crisis" by U.N. secretary general António Guterres, [8], Public Citizen reported that in 2018, less than 10% of articles in top-50 U.S. newspapers used the terms "crisis" or "emergency". [46] In 2019, it was also estimated that only 3.5% of national television news segments referred to climate change as a crisis or emergency in 2018. [47] (50 of 1400). Public Citizen reported a tripling in the number of mentions (150) in just the first four months of 2019. [46]

On May 17, 2019 The Guardian formally updated its style guide to favor "climate emergency, crisis or breakdown" and "global heating". [48] [49] Editor-in-Chief Katharine Viner explained, "We want to ensure that we are being scientifically precise, while also communicating clearly with readers on this very important issue. The phrase ‘climate change’, for example, sounds rather passive and gentle when what scientists are talking about is a catastrophe for humanity." [50] The Guardian became a lead partner in Covering Climate Now, an initiative of news organizations founded in 2019 by the Columbia Journalism Review and The Nation to address the need for stronger climate coverage. [51] [52] In May 2019, Al Gore's Climate Reality Project (2011–) promoted an open petition asking news organizations to use "climate crisis" in place of "climate change" or "global warming", [2] saying "it’s time to abandon both terms in culture". [53] Likewise, the Sierra Club, the Sunrise Movement, Greenpeace, and other environmental and progressive organizations joined in a June 6, 2019 Public Citizen letter to news organizations, [46] urging them to call climate change and human inaction "what it is–a crisis–and to cover it like one". [45]

Conversely, in June 2019 the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation updated its language guide to read "Climate crisis and climate emergency are OK in some cases as synonyms for 'climate change'. But they're not always the best choice... For example, 'climate crisis' could carry a whiff of advocacy in certain political coverage". [54] The update prompted journalism professor Sean Holman to say that "journalists are being torn by two competing values right now. The first is our job to tell the truth. We are, over and above anything else, society's professional truth-seekers and truth-tellers. But the second value that we think is important is appearing unbiased, because if we appear unbiased then people will believe that we are telling the truth. I think what's happened here is that large swaths of society, including entire political parties and governments as well as voters, don't believe in the truth. And so by telling the truth, to those individuals we appear to be biased." [54] Likewise, The New York Times did not adopt the phrases "climate emergency" or "climate crisis" and in June 2019, 70 climate activists were arrested for demonstrating outside its offices. This demonstration had, among the other pressure campaigns, swayed the City Council to make New York City the largest urban locaity to formally adopt a climate emergency declaration. [55]

In November 2019, the Oxford Dictionaries included "climate crisis" on its short list for word of the year 2019, the designation designed to recognize terms that "reflect the ethos, mood, or preoccupations of the passing year" and that should have "lasting potential as a term of cultural significance". [56] The same month, Indian English-language daily Hindustan Times had formally adopted the term because "climate change" "does not correctly reflect the enormity of the existential threat". [57]

Other languages

In June 2019, Spanish news agency EFE announced its preferred phrase crisis climática (climate crisis), with Grist journalist Kate Yoder remarking that "these terms were popping up everywhere", adding that "climate crisis" is "having a moment". [46] Similarly, Warsaw newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza uses the term "climate crisis" instead of "climate change", an editor-in-chief of its Gazeta na zielono (newspaper in green) section describing climate change as one of the most important topics the paper has ever covered. [58]

In 2021, Helsinki newspaper Helsingin Sanomat created a free variable font called "Climate Crisis" having eight different weights that correlate with Arctic sea ice decline, visualizing how ice melt has changed over the decades. [59] The newspaper's art director posited that the font both evokes the aesthetics of environmentalism and inherently constitutes a data visualization graphic. [59]

We cannot solve a crisis without treating it as a crisis. Nor can we treat something like a crisis unless we understand the emergency.

Greta Thunberg, December 10, 2020 [60]

Effectiveness

Before the widespread adoption of the crisis rhetoric in 2019, multiple sources have described the struggle of communicating the gravity of the issue effectively, and of incorporating it into policy analysis. [61] [62] [63] [64] In the early 2010s, some scholars have suggested that, absent a radical change in perspective, political action on dealing with the future impacts of climate change is hindered by the perceived value of today's actions to prevent tomorrow's impacts being equivalent to zero. [65] [66] In 2018, Esquire chronicled the history of scientific frustration with their warnings being treated akin to sensational entertainment by the media, [67] while an earlier article from The Atlantic described that the conflation of warnings into a generalized picture of an apocalypse was acting as a hindrance to effective action. [68]

A 2013 study (N=224, mostly college freshmen) surveyed participants' responses after they had read different simulated written articles. [14] The study concluded that "climate crisis was most likely to create backlash effects of disbelief and reduced perceptions of concern, most likely due to perceptions of exaggeration", and suggested that other terms ("climatic disruption" and "global warming") should instead be used, particularly when communicating with skeptical audiences. [14] On the other hand, an early 2019 neuroscientific study (N=120, divided equally among Republicans, Democrats and independents) [69] by an advertising consulting agency involved electroencephalography (EEG) and galvanic skin response (GSR) measurements. [15] The study, measuring responses to the terms "climate crisis", "environmental destruction", "environmental collapse", "weather destabilization", "global warming" and "climate change", found that Democrats had a 60% greater emotional response to "climate crisis" than to "climate change", with the corresponding response among Republicans tripling. [69] "Climate crisis" is said to have "performed well in terms of responses across the political spectrum and elicited the greatest emotional response among independents". [69] The study concluded that the term "climate crisis" elicited stronger emotional responses than "neutral" and "worn out" terms like "global warming" and "climate change", thereby encouraging a sense of urgency—though not so strong a response as to cause cognitive dissonance that would cause people to generate counterarguments. [15] However, the CEO of the company conducting the study noted generally that visceral intensity can backfire, specifying that another term with an even stronger response, "environmental destruction", "is likely seen as alarmist, perhaps even implying blame, which can lead to counterarguing and pushback." [69]

In September 2019, Bloomberg News journalist Emma Vickers posited that crisis terminology—though the issue was one, literally, of semantics—may be "showing results", citing a 2019 poll by The Washington Post and the Kaiser Family Foundation saying that 38% of U.S. adults termed climate change "a crisis" while an equal number called it "a major problem but not a crisis". [4] Five years earlier, U.S. adults considering it a crisis numbered only 23%. [70] Conversely, use of crisis terminology in various non-binding climate emergency declarations has not been effective (as of September 2019) in making governments "shift into action". [5]

Concerns about crisis terminology

Some commentators have written that "emergency framing" may have several disadvantages. [16] Specifically, such framing may implicitly prioritize climate change over other important social issues, thereby encouraging competition among activists rather than cooperation and sidelining dissent within the climate change movement itself. [16] It may suggest a need for solutions by government, which provides less reliable long-term commitment than does popular mobilization, and which may be perceived as being "imposed on a reluctant population". [16] Finally, it may be counterproductive by causing disbelief (absent immediate dramatic effects), disempowerment (in the face of a problem that seems overwhelming), and withdrawal—rather than providing practical action over the long term. [16]

Along similar lines, Australian climate communication researcher David Holmes has commented on the phenomenon of "crisis fatigue", in which urgency to respond to threats loses its appeal over time. [6] Holmes said there is a "limited semantic budget" for such language, cautioning that it can lose audiences if time passes without meaningful policies addressing the emergency. [6]

Others have written that, whether "appeals to fear generate a sustained and constructive engagement" is clearly a highly complex issue but that the answer is "usually not", with psychologists noting that humans' responses to danger (fight, flight, or freeze) can be maladaptive. [71] Agreeing that fear is a "paralyzing emotion", Sander van der Linden, director of the Cambridge Social Decision-Making Lab, favors "climate crisis" over other terms because it conveys a sense of both urgency and optimism, and not a sense of doom because "people know that crises can be avoided and that they can be resolved". [8]

Climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe warned in early 2019 that crisis framing is only "effective for those already concerned about climate change, but complacent regarding solutions". [17] She added that it "is not yet effective" for those who perceive climate activists "to be alarmist Chicken Littles", positing that "it would further reinforce their pre-conceived—and incorrect—notions". [17]

In June 2019, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation updated its language guide to read that the term climate crisis "could carry a whiff of advocacy in certain political coverage". [54]

Two German journalists have respectively warned that "crisis" may be wrongly understood to suggest that climate change is "inherently episodic"—crises being "either solved or they pass"—or as a temporary state before a return to normalcy that is in fact not possible. [72]

Related terminology

Research has shown that what a phenomenon is called, or how it is framed, "has a tremendous effect on how audiences come to perceive that phenomenon" [14] and "can have a profound impact on the audience’s reaction". [8] Climate change and its actual and hypothetical effects are sometimes described in terms other than climate crisis. (Following dates aren't necessarily the first use of such terms.)

- "climate catastrophe" (used with reference to a 2019 David Attenborough documentary, [73] the 2019–20 Australian bushfire season, [74] and the 2022 Pakistan floods [75])

- "threats that impact the earth" (World Wildlife Fund, 2012—) [76]

- "climate breakdown" (climate scientist Peter Kalmus, 2018) [77]

- "climate chaos" (The New York Times article title, 2019; [78] U.S. Democratic candidates, 2019; [37] and an Ad Age marketing team, 2019) [8]

- "climate ruin" (U.S. Democratic candidates, 2019) [37]

- "global heating" ( Richard A. Betts, Met Office U.K., 2018) [79]

- "climate emergency" ( 11,000 scientists' warning letter [10] in BioScience, [80] [81] and in The Guardian, [4] [48] both 2019),

- "ecological breakdown", "ecological crisis" and "ecological emergency" (all set forth by climate activist Greta Thunberg, 2019) [82]

- "global meltdown", "Scorched Earth", "The Great Collapse", and "Earthshattering" (an Ad Age marketing team, 2019) [8]

- "climate disaster"(The Guardian, 2019) [83]

- "climate calamity" (Los Angeles Times, 2022) [84]

- "climate havoc" (The New York Times, 2022) [85]

- "climate pollution", "carbon pollution" (Grist, 2022) [86]

In addition to "climate crisis", various other terms have been investigated for their effects on audiences, including "global warming", "climate change", and "climatic disruption", [14] as well as "environmental destruction", "weather destabilization", and "environmental collapse". [15] Some of these terms may not fully represent the scientific consensus.

See also

- Climate emergency declaration

- Climate communication

- Environmental communication

- Climate justice

- Green New Deal

- Media coverage of climate change

- Public opinion on global warming

- The Climate Mobilization

- World War Zero

- World Scientists' Warning to Humanity

- Extinction Rebellion

- School Strike for Climate

References

-

^ Rosenblad, Kajsa (December 18, 2017).

"Review: An Inconvenient Sequel". Medium (Communication Science news and articles). Netherlands.

Archived from the original on March 29, 2019.

... climate change, a term that Gore renamed to climate crisis

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sobczyk, Nick (July 10, 2019). "How climate change got labeled a 'crisis'". E & E News (Energy & Environmental News). Archived from the original on October 13, 2019.

- ^ a b c Center for International Environmental Law. (1990). "Selected International Legal Materials on Global Warming and Climate Change". American University International Law Review. 5 (2): 515. Archived from the original on June 23, 2020. Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Vickers, Emma (September 17, 2019). "When Is Change a 'Crisis'? Why Climate Terms Matter". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on September 20, 2019.

- ^ a b c Mukheibir, Pierre; Mallam, Patricia (September 30, 2019). "Climate crisis – what's it good for?". The Fifth Estate. Australia. Archived from the original on October 1, 2019.

- ^ a b c Bedi, Gitanjali (January 3, 2020). "Is it time to rethink our language on climate change?". Monash Lens. Monash University (Melbourne, Australia). Archived from the original on January 31, 2020.

- ^ "The Club of Rome Climate Emergency Plan". The Club of Rome. Archived from the original on December 8, 2019. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Rigby, Sara (January 3, 2020). "Climate change: should we change the terminology?". BBC Science Focus. Archived from the original on January 3, 2020.

- ^ a b Gilding, Paul (September 17, 2019). "Why I welcome a climate emergency". Nature.

- ^ a b c Ripple, William J.; Wolf, Christopher; Newsome, Thomas M.; Barnard, Phoebe; Moomaw, William R. (January 1, 2020). "World Scientists' Warning of a Climate Emergency". BioScience. 70 (1): 8–12. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biz088. ISSN 0006-3568. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c Ripple, William J.; Wolf, Christopher; Newsome, Thomas M.; Gregg, Jillian W.; et al. (July 28, 2021). "World Scientists' Warning of a Climate Emergency 2021". BioScience. 71 (9): biab079. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biab079. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ^ Samenow, Jason (January 29, 2018). "Debunking the claim 'they' changed 'global warming' to 'climate change' because warming stopped". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 29, 2019.

- ^ Maibach, Edward; Leiserowitz, Anthony; Feinberg, Geoff; Rosenthal, Seth; Smith, Nicholas; Anderson, Ashley; Roser-Renouf, Connie (May 2014). "What's in a Name? Global Warming versus Climate Change". Yale Project on Climate Change, Center for Climate Change Communication. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.10123.49448. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f "Words That (Don't) Matter: An Exploratory Study of Four Climate Change Names in Environmental Discourse / Investigating the Best Term for Global Warming". naaee.org. North American Association for Environmental Education. 2013. Archived from the original on November 11, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Yoder, Kate (April 29, 2019). "Why your brain doesn't register the words 'climate change'". Grist. Archived from the original on July 24, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Hodder, Patrick; Martin, Brian (September 5, 2009). "Climate Crisis? The Politics of Emergency Framing" (PDF). Economic and Political Weekly. 44 (36): 53, 55–60. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 10, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Dean, Signe (May 25, 2019). "ScienceAlert Editor: Yes, It's Time to Update Our Climate Change Language". Science Alert. Archived from the original on July 31, 2019.

-

^ Cite error: The named reference

WG3_Chapter3was invoked but never defined (see the help page). -

^ Cite error: The named reference

NatureWG1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). -

^ Cite error: The named reference

Ghastlywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "What does climate crisis mean? / Where does climate crisis come from?". dictionary.com. December 2019. Archived from the original on December 21, 2019.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (November 5, 2019). "Climate crisis: 11,000 scientists warn of 'untold suffering'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on January 14, 2020.

- ^ Marshall, Michael (September 20, 2020). "The tipping points at the heart of the climate crisis". The Guardian.

- ^ Armstrong McKay, David; Abrams, Jesse; Winkelmann, Ricarda; Sakschewski, Boris; Loriani, Sina; Fetzer, Ingo; Cornell, Sarah; Rockström, Johan; Staal, Arie; Lenton, Timothy (September 9, 2022). "Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points". Science. 377 (6611): eabn7950. doi: 10.1126/science.abn7950. hdl: 10871/131584. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 36074831. S2CID 252161375.

- ^ Baker, Harry (September 15, 2022). "Climate "points of no return" may be much closer than we thought". livescience.com. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ Armstrong McKay, David (September 9, 2022). "Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points – paper explainer". climatetippingpoints.info. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ Lenton, Timothy M.; Rockström, Johan; Gaffney, Owen; Rahmstorf, Stefan; Richardson, Katherine; Steffen, Will; Schellnhuber, Hans Joachim (2019). "Climate tipping points — too risky to bet against". Nature. 575 (7784): 592–595. Bibcode: 2019Natur.575..592L. doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-03595-0. hdl: 10871/40141. PMID 31776487. S2CID 208330359.

- ^ "Critical measures of global heating reaching tipping point, study finds". The Guardian. July 27, 2021. Archived from the original on August 22, 2021.

- ^ "Climate warnings highlight the urgent need for action ahead of COP27". New Scientist. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ^ Ripple, William J; Wolf, Christopher; Gregg, Jillian W; Levin, Kelly; Rockström, Johan; Newsome, Thomas M; Betts, Matthew G; Huq, Saleemul; Law, Beverly E; Kemp, Luke; Kalmus, Peter; Lenton, Timothy M (October 26, 2022). "World Scientists' Warning of a Climate Emergency 2022". BioScience. 72 (12): 1149–1155. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biac083.

- ^ Atwoli, Lukoye; Baqui, Abdullah H; Benfield, Thomas; Bosurgi, Raffaella; Godlee, Fiona; Hancocks, Stephen; Horton, Richard; Laybourn-Langton, Laurie; Monteiro, Carlos Augusto; Norman, Ian; Patrick, Kirsten; Praities, Nigel; Olde Rikkert, Marcel G M; Rubin, Eric J; Sahni, Peush; Smith, Richard; Talley, Nicholas J; Turale, Sue; Vázquez, Damián (September 5, 2021). "Call for emergency action to limit global temperature increases, restore biodiversity, and protect health". BMJ. 374: n1734. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1734. PMC 8414196. PMID 34483099.

- ^ "United States House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis / About". climatecrisis.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. 2019. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Crediting Shawna Faison and House Creative Services.

- ^ Pyper, Julia (June 7, 2019). "UN Chief Guterres: The Status Quo on Climate Policy 'Is a Suicide'". greentechmedia.com. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ "IPCC adaptation report 'a damning indictment of failed global leadership on climate'". UN News. February 28, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ "Secretary-General Warns of Climate Emergency, Calling Intergovernmental Panel's Report 'a File of Shame', While Saying Leaders 'Are Lying', Fuelling Flames". UN News. April 4, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ Meyer, Robinson (December 28, 2018). "Democrats Establish a New House 'Climate Crisis' Committee". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on July 25, 2019.

- ^ a b c Kormann, Carolyn (July 11, 2019). "The Case for Declaring a National Climate Emergency". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on October 6, 2019.

- ^ Smith-Schoenwalder, Cecelia (November 3, 2022). "Why the Biden Administration's Motivation for a Climate Change Emergency Declaration Has Waned". US News. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ "Pacific Island States Declare Climate Crisis". 350.org. Archived from the original on September 22, 2019. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ "Australian climate change policies face growing criticism from Pacific leaders". ABC News. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ Anna, Cara (September 27, 2020). "Leaders to UN: If virus doesn't kill us, climate change will". AP NEWS. Associated Press.

- ^ Gabbatiss, Josh (March 28, 2019). "Labour declares national 'environment and climate emergency'". The Independent. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ "UK Parliament declares climate change emergency". BBC News. May 1, 2019. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- ^ "Pope on climate crisis: Time is running out, decisive action needed - Vatican News". vaticannews.va. June 14, 2019. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ a b "Letter to Major Networks: Call it a Climate Crisis – and Cover it Like One". citizen.org. Public Citizen. June 6, 2019. Archived from the original on October 17, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Yoder, Kate (June 17, 2019). "Is it time to retire 'climate change' for 'climate crisis'?". Grist. Archived from the original on June 29, 2019.

-

^

"Call it a Climate Crisis". ActionNetwork.org. Archived from the original on May 17, 2019. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

{{ cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown ( link) Earliest Wayback Machine archive is May 17, 2019. - ^ a b Hickman, Leo (May 17, 2019). "The Guardian's editor has just issued this new guidance to all staff on language to use when writing about climate change and the environment..." Journalist Leo Hickman on Twitter. Archived from the original on November 15, 2019. Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (May 17, 2019). "Why The Guardian is changing the language it uses about the environment". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (May 17, 2019). "Why The Guardian is changing the language it uses about the environment / From now, house style guide recommends terms such as 'climate crisis' and 'global heating'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 6, 2019.

- ^ Guardian staff (April 12, 2021). "The climate emergency is here. The media needs to act like it". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021.

- ^ Hertsgaard 2019.

- ^ "Why Do We Call It the Climate Crisis?". climaterealityproject.org. The Climate Reality Project. May 1, 2019. Archived from the original on September 24, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Treat climate change like the crisis it is, says journalism professor". Interviewed by Gillian Findlay. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. July 5, 2019. Archived from the original on July 7, 2019. • Archive of CBC quote in Osoyoos Times.

- ^ Barnard, Anne (July 5, 2019). "A 'Climate Emergency' Was Declared in New York City. Will That Change Anything?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 11, 2019.

- ^ Zhou, Naaman (November 20, 2019). "Oxford Dictionaries declares 'climate emergency' the word of 2019". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 21, 2019. "Climate emergency" was named word of the year.

- ^ "Recognising the climate crisis". Hindustan Times. November 24, 2019. Archived from the original on November 25, 2019.

- ^ "Do European media take climate change seriously enough?". European Journalism Observatory (ejo.ch). Switzerland. February 18, 2020. Archived from the original on February 27, 2020.

- ^ a b Smith, Lilly (February 16, 2021). "This chilling font visualizes Arctic ice melt". Fast Company. Archived from the original on February 23, 2021.

- ^ Common Dreams (December 11, 2020). "Greta Thunberg Warns Humanity 'Still Speeding in Wrong Direction' on Climate". Ecowatch.com. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021.

- ^ Swyngedouw, Erik (May 24, 2010). "Apocalypse Forever?". Theory, Culture & Society. 27 (2–3): 213–232. doi: 10.1177/0263276409358728. S2CID 145576402.

- ^ Feinberg, Matthew; Willer, Robb (December 9, 2010). "Apocalypse Soon?". Psychological Science. 22 (1): 34–38. doi: 10.1177/0956797610391911. PMID 21148457. S2CID 39153081.

- ^ Swyngedouw, Erik (March 2013). "Apocalypse Now! Fear and Doomsday Pleasures". Capitalism Nature Socialism. 24 (1): 9–18. doi: 10.1080/10455752.2012.759252. S2CID 143450923.

- ^ Kopits, Elizabeth; Marten, Alex; Wolverton, Ann (December 9, 2013). "Incorporating 'catastrophic' climate change into policy analysis". Climate Policy. 14 (5): 637–664. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2014.864947. S2CID 154835016.

- ^ Methmann, Chris; Rothe, Delf (August 15, 2012). "Politics for the day after tomorrow: The logic of apocalypse in global climate politics". Security Dialogue. 43 (4): 323–344. doi: 10.1177/0967010612450746. S2CID 144721387.

- ^ Stoekl, Allan (2013). ""After the Sublime," after the Apocalypse: Two Versions of Sustainability in Light of Climate Change". Diacritics. 41 (3): 40–57. doi: 10.1353/dia.2013.0013. S2CID 144766054.

- ^ Richardson, John H. (July 20, 2018). "When the End of Human Civilization Is Your Day Job". Esquire.

- ^ Gross, Matthew Barrett; Gilles, Mel (April 23, 2012). "How Apocalyptic Thinking Prevents Us from Taking Political Action". The Atlantic.

- ^ a b c d Berardelli, Jeff (May 16, 2019). "Does the term "climate change" need a makeover? Some think so — here's why". CBS News. Archived from the original on November 8, 2019.

- ^ Guskin, Emily; Clement, Scott; Achenbach, Joel (December 9, 2019). "Americans broadly accept climate science, but many are fuzzy on the details". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 9, 2019.

- ^ Moser, Susan C.; Dilling, Lisa (December 2004). "Making Climate Hot / Communicating the Urgency and Challenge of Global Climate Change" (PDF). University of Colorado. pp. 37–38. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 10, 2017. Footnotes 33–37. Also published: December 2004, Environment, volume 46, no. 10, pp. 32–46 Archived May 18, 2020, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Reimer, Nick (September 19, 2019). "Climate Change or Climate Crisis – What's the right lingo?". Germany. Clean Energy Wire. Archived from the original on November 15, 2019.

- ^ "Climate Change: The Facts". Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC Australia). August 2019. Archived from the original on November 11, 2019.

- ^ Flanagan, Richard (January 3, 2020). "Australia Is Committing Climate Suicide". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 3, 2020.

- ^ Baloch, Shah Meer (August 28, 2022). "Pakistan declares floods a 'climate catastrophe' as death toll tops 1,000". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 28, 2022.

- ^ "Tackling Threats That Impact the Earth". World Wildlife Fund. 2019. Archived from the original on October 2, 2019.

- ^ Kalmus, Peter (August 29, 2018). "Stop saying "climate change" and start saying "climate breakdown."". @ClimateHuman on Twitter. Archived from the original on November 11, 2019.

- ^ Shannon, Noah Gallagher (April 10, 2019). "Climate Chaos Is Coming — and the Pinkertons Are Ready". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 5, 2019.

- ^ Watts, Jonathan (December 16, 2018). "Global warming should be called global heating, says key scientist". Grist. Archived from the original on August 24, 2019.

- ^ Ryan, Jackson (November 5, 2019). "'Climate emergency': Over 11,000 scientists sound thunderous warning / The dire words are a call to action". CNET. Archived from the original on November 11, 2019.

- ^ McGinn, Miyo (November 5, 2019). "11,000 scientists say that the 'climate emergency' is here". Grist. Archived from the original on December 14, 2019.

- ^ Picazo, Mario (May 13, 2019). "Should we reconsider the term 'climate change'?". The Weather Network (CA). Archived from the original on November 12, 2019. includes link to Thunberg's tweet: ● Thunberg, Greta (May 4, 2019). "It's 2019. Can we all now please stop saying "climate change" and instead call it what it is". twitter.com/GretaThunberg. Archived from the original on November 6, 2019. Retrieved November 11, 2019.

- ^ Goldrick, Geoff (December 19, 2019). "2019 has been a year of climate disaster. Yet still our leaders procrastinate". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 31, 2019.

- ^ Roth, Sammy (July 28, 2022). "August is coming. Prepare for climate calamity". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022.

- ^ Sengupta, Somini (September 27, 2022). "Who pays for climate havoc?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022.

- ^ Yoder, Kate (September 29, 2022). "'It makes climate change real': How carbon emissions got rebranded as 'pollution'". Grist. Archived from the original on September 29, 2022.

Cite error: A

list-defined reference named "FastCo_20211206" is not used in the content (see the

help page).

Cite error: A

list-defined reference named "PNAS_20220823" is not used in the content (see the

help page).

Further reading

- Bell, Alice R. (2021). Our Biggest Experiment: an epic history of the climate crisis (First ed.). Berkeley, California. ISBN 978-1-64009-433-8. OCLC 1236092035

- Feldman, Lauren; Hart, P. Sol (November 16, 2021). "Upping the ante? The effects of "emergency" and "crisis" framing in climate change news". Climatic Change. 169 (10): 10. Bibcode: 2021ClCh..169...10F. doi: 10.1007/s10584-021-03219-5. S2CID 244119978.

- Hall, Aaron (November 27, 2019). "Renaming Climate Change: Can a New Name Finally Make Us Take Action". Ad Age. Archived from the original on December 21, 2019. (advertising perspective by a "professional namer")

- Hertsgaard, Mark (August 28, 2019). "Covering Climate Now signs on over 170 news outlets". Columbia Journalism Review. Archived from the original on September 22, 2019.

- "Act now and avert a climate crisis (editorial)". Nature. September 15, 2019. Archived from the original on September 22, 2019. (Nature joining Covering Climate Now.)

- Visram, Talib (December 6, 2021). "The language of climate is evolving, from 'change' to 'catastrophe'". Fast Company. Archived from the original on December 6, 2021.

- Zillman, John W. (2009). "A History of Climate Activities". World Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on August 16, 2019. Vol. 58 (3).

External links

- Covering Climate Now (CCNow), a collaboration among news organizations "to produce more informed and urgent climate stories" ( archive)

- "Climate crisis", dictionary.com ( archive)