Central Park is an 843-acre (341 ha) urban park in Manhattan, New York City. It is roughly bounded by Fifth Avenue on the east, Central Park West (Eighth Avenue) on the west, Central Park South (59th Street) on the south, and Central Park North (110th Street) on the north.

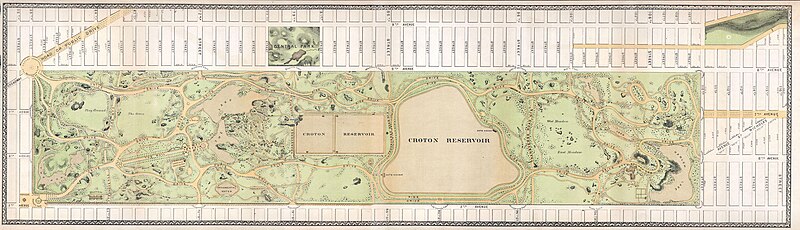

Central Park was established in 1857 on 778 acres (315 ha) of land acquired by the city. In 1858, landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted and architect/landscape designer Calvert Vaux won a design competition to improve and expand the park with a plan they titled the "Greensward Plan". Construction began the same year, and the park's first area was opened to the public in the winter of 1858. Construction north of the park continued during the American Civil War in the 1860s, and the park was expanded to its current size in 1873.

Initially, Central Park was so popular that it began to decline through overuse by the late 19th century. In the 1930s, New York City parks commissioner Robert Moses started a program to clean up Central Park. Another decline in the late 20th century spurred the creation of the Central Park Conservancy in 1980, which refurbished many parts of the park during the 1980s and 1990s.

Planning

Between 1821 and 1855, New York City nearly quadrupled in population. As the city expanded northward up Manhattan Island, people were drawn to the few existing open spaces, mainly cemeteries, to get away from the noise and chaotic life in the city. [1] [2] The Commissioners' Plan of 1811, the outline for Manhattan's modern street grid, included several smaller open spaces but not Central Park. [2] [3] As such, John Randel Jr. had surveyed the grounds for the construction of intersections within the modern-day park site. The only remaining surveying bolt from his survey is embedded in a rock located north of the present Dairy and the 65th Street Transverse, marking the location where West 65th Street would have intersected Sixth Avenue. [4] [5]

Possible sites

By the 1840s, members of the city's elite were publicly calling for the construction of a new large park in Manhattan. Proponents said that the park would serve three purposes: abetting good health, improving the behavior of the "disorderly classes", and showcasing the refinement of the city's elite. [1] At the time, Manhattan's seventeen squares comprised a combined 165 acres (67 ha) of land, the largest of which was the 10-acre (4.0 ha) Battery Park at Manhattan island's southern tip. [6] This constituted less than one percent of Manhattan's total area. [2]

The first plans for such a space were said to have originated from an anonymous wealthy individual who had returned from Europe and wrote letters about the importance of a green space in Manhattan. [7] New York Evening Post editor William Cullen Bryant wrote about the need for such a park in his 1844 editorial "A New Park". [2] [8] [9] [10] Andrew Jackson Downing, one of the first American landscape designers, also wrote letters in 1849 and 1850, extolling the benefits of constructing a large landscaped park similar to Paris's Bois de Boulogne or London's Hyde Park. [8] [10] [11] [12] The historian Charles A. Beard writes that there might have been another motive to create a large public park, in that it would raise surrounding property values. [7] [13] The plan gained enough support that both candidates in the 1850 New York City mayoral election, Fernando Wood and Ambrose Kingsland, supported the construction of a large park. [12]

One of the first sites considered for a large park was Jones's Wood, a 160-acre (65 ha) tract of land between 66th and 75th Streets on the Upper East Side. Bryant preferred this option because at the time, Jones's Wood was still relatively undeveloped. [12] [14]: 451 The area was occupied by multiple wealthy families who objected to the taking of their land, particularly the Joneses and Schermerhorns. [14]: 451 Residents of Manhattan's West Side also objected for a different reason: it would be too far away for them to reach, compared to a centrally located park. [15] Downing stated that he would prefer a park of at least 500 acres (200 ha) at any location from 39th Street to the Harlem River. [12] [14]: 452–453 [16] The New York State Legislature unanimously voted to acquire Jones's Wood in 1851. [17] [18] The decision was highly controversial, and newspapers continued to advocate for alternate sites for a large park, and the general public was not well-informed about the issue. [18] One popular suggestion was to enlarge the existing Battery Park, so as a compromise, New York City's aldermen voted for both the Battery Park and Jones's Wood bills. [15] [19] Following the passage of the 1851 bill to acquire Jones's Wood, the Schermerhorns and Joneses successfully obtained an injunction to block the acquisition, and the transaction was invalidated as unconstitutional. [20] [21]

A second possible site for a large public park was a 750-acre (300 ha) area labeled as "the Central Park", bounded by 59th and 106th Streets between Fifth and Eighth Avenues. [20] [22] [23] Central Park was proposed by Croton Aqueduct Board president Nicholas Dean, who chose the site because the Croton Aqueduct's 35-acre (14 ha), 150-million-US-gallon (570×106 L) collecting reservoir would be in the geographical center. [20] [22] Central Park was believed to be too rocky and marshy for development, but it was five times larger than Jones's Wood, and was closer to the West Side than Jones's Wood was. [20] The Schermerhorns and Lower Manhattan's merchants endorsed Central Park over Jones's Wood, and the Central Park plan gradually gained support from a variety of groups. [24]

Supporters of Jones's Wood continued to lobby for their site. Some Manhattanites organized a petition against the new location, which gained thousands of signatures. [25] Jones's Wood advocates used increasingly misleading tactics to force the city to purchase Jones's Wood. [26] [27] In July 1853, the New York State Legislature passed the Central Park Act, authorizing the purchase of the present-day site of Central Park. [17] [26] In the same session, state senator James Beekman proposed legislation that would allow the city to convene a commission to study Jones's Wood. After the bill was passed, Beekman changed the bill's language so that the city was required to purchase the land. [26] [27] However, Beekman's legislation was nullified in July 1854 after objections from the Schermerhorns and Joneses. [17] [26]

Land acquisition

The Central Park Act authorized a board of five commissioners to start purchasing land for a park, as well as create a Central Park Fund to raise money. [14]: 458 [28] [29] The board of land commissioners was convened in November 1853, [29] [30] and they started conducting property assessments on more than 34,000 lots in and near Central Park. [31] The Central Park Fund, a stock issue, was intended to provide the necessary funding to begin work on the park. [30] [32]

Around this time, there were proposals to reduce Central Park's area by half due to concerns about the declining economy, which had started in January 1854 and would culminate in the Panic of 1857. Mayor Jacob Aaron Westervelt proposed truncating the southern boundary (from 59th to 72nd Streets), as he was concerned about overspending and the state's regulatory overreach in its decision to designate such a large area. There were several competing proposals to curtail the park, but no decision was made until March 1855, when the city's board of councilmen voted 14-to-3 to trim both the lower thirteen blocks (from 59th to 72nd Streets) and four hundred feet from each side of Central Park. [33] [34] [35] Shortly afterward, Westervelt's successor Fernando Wood vetoed the measure. [33] [35] The Central Park land commissioners had completed their assessments by July 1855, and the New York Supreme Court confirmed this work the following February. [35] [30]

When Central Park was approved in 1853, the site was occupied by free blacks, Native Americans, and Irish and German immigrants who had purchased land, raised livestock, built churches and cemeteries, and lived there as a community since 1825. [36] [37] The community was referred to in pejorative terms, and the residents were often described as "wretched" and "debased". [38] [39] Central Park's proponents had gained support for their position by stating that the project would remove what they deemed as shanty towns and their denizens. [40] [27] The surrounding area was filled with such varied land uses as mental asylums, bone disposal plants, and country estates. [41] Before the construction of the park could start, the area had to be cleared of its inhabitants. [42] [43] The Central Park land commission's report was released in October 1855, [31] [44] and clearing began shortly thereafter. [45] Most of the Central Park site's residents lived in small villages, such as Pigtown [46] [47] or Seneca Village; [48] or in the school and convent at Mount St. Vincent's Academy. [49] Approximately 1,600 residents were evicted under eminent domain from 1855 to 1857. Seneca Village and parts of the other communities were razed to make room for the park. [48] [50] [51]

Central Park's supporters also promoted their scheme with the claim that building the park would cost a relatively cheap $1.7 million. [52] However, this failed to take into account the cost of landscaping, and land acquisition alone ended costing almost three times as much. [53] [29] [31] Over $5 million was to be paid to 561 separate landowners who owned property in the park itself, while surrounding property owners were subject to another $1.7 million in tax assessments. [35] The twelve-block tract between 106th and 110th Streets at the park's northern end, which was added later, [54] cost an additional $1.18 million. [30] When the land had been fully purchased, the total cost of the land was $7.39 million, more than the price that the United States paid for Alaska a few years afterward. [30] [55] [56]

Property owners objected that they would be receiving too little money, because the land commission was offering an average of $700 per lot while some of the landowners wanted $800 per lot. [31] [51] Furthermore, the city had auctioned off 800 lots within the Central Park site in 1852, and many of the buyers filed complaints after Central Park's creation was announced. [31] In the end, very few land assessments were revised after the fact, and most of the landowners made substantial profits from the purchase of Central Park's land, except for those who bought land at the 1852 city auction. [57] The land assessments worked to landowners' benefit, as the value of the surrounding land started rising significantly in the mid-1860s. [58] The completion of Central Park immediately increased the surrounding area's real estate prices, in some cases by up to 700 percent between 1858 and 1870. [13] [57] It also resulted in the creation of the current system of zoning in Upper Manhattan. [59]

Design

Park commissioners and Egbert Viele's plan

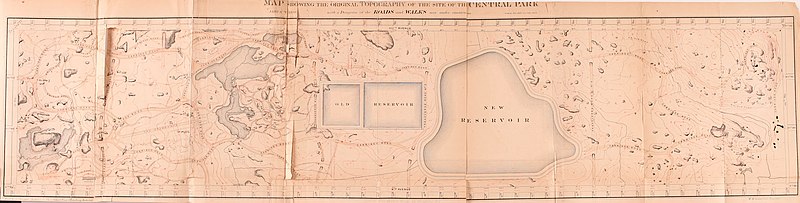

In June 1856, Fernando Wood appointed a "consulting board" of seven people, headed by author Washington Irving. The consulting board was organized purportedly to inspire public confidence in the proposed park. [62] [39] Wood hired military engineer Egbert Ludovicus Viele as the chief engineer of the park, tasking Viele with doing a topographical survey of the site. [43] [63] [61] [64] A team of four surveyors and twelve other laborers were assigned to survey the land. They found that the future park site had more than 150,000 plants, as well as a thick covering of brush and undergrowth, particularly in the site's northern section. [65] Viele released the results of his survey in the "First Annual Report on the Improvement of the Central Park", dated January 1, 1857, in which he named 43 plant species on the park site. The same year, Charles Rawolle and Ignatz Anton Pilát published a competing survey where they outlined 280 plant species. [66]

On April 17, 1857, the state legislature passed a bill to authorize the appointment of a bipartisan group of eleven park commissioners, who exclusively controlled the planning and construction process. [67]: PDF pp. 8–12 [68]: 474 [69] This was ostensibly done to prevent Wood from controlling the construction of Central Park. [68]: 474 [66] From the outset, the commissioners often conflicted over even minor details due to partisan disagreements. While the president James E. Cooley and three other members were Democrats, the remaining seven members were Republicans. [62] In September 1857, the commission created positions for nine "officers of the commission", each of which was assigned to a separate task. [67]: PDF pp. 22–24 Among these officers was Frederick Law Olmsted, superintendent of Central Park, who was hired because of his lack of ties to political forces in either party. [70] [71] [72]

Viele is credited with creating the first formal proposal for Central Park. Though Viele was officially hired in 1857, he had started conducting unofficial surveys in 1853, as soon as the park's plans were announced, in anticipation of the adoption of his plans for the park. [39] [43] [45] Viele's plans revolved around the natural topography of the land and incorporated the Croton reservoir in the center of the park site. It also included a cricket ground in the southwest corner, a parade ground on the east side near the current Metropolitan Museum of Art, and various lakes and streams at the sites of existing swamps. The plan was to cost $1.5 million, less than what was originally budgeted for the park. [61] However, because Viele had been appointed by Wood (whom the commissioners disliked), the commissioners disregarded his plan and retained him only to complete the topographical surveys. [73] [74] The topographical surveys were completed by late 1857. [65]

Landscape contest

The Central Park commission started a landscape design contest in April 1857, shortly after Olmsted had been hired as park superintendent. [74] [75] [76] [77] There were four overarching ideals that affected the possible designs: simplicity, variety, naturalism, and civic pride. [73] Thirty-three firms or organizations filed official plans, though written copies exist of only three plans. Most of the applicants were Americans and more than half were city residents. [76] [78] Many of these plans were little more than a drawing or general concept. [78]

The applications were required to contain extremely detailed specifications, as mandated by the board. In particular, the final plans were required to include at least four east-west transverse roads through the park, a parade ground of 20 to 40 acres (8.1 to 16.2 ha), and at least three playgrounds of between 3 and 10 acres (1.2 and 4.0 ha). [67]: PDF pp. 29–30 [76] [78] [75] Other specifications included a site for exhibitions or concerts; a site for a grand fountain and "prospect tower"; a flower garden of 2 to 3 acres (0.81 to 1.21 ha); and a lake that could double as an ice skating ground during the winters. The total cost of implementing the design could not exceed $1.5 million, which was the budget approved by the New York state legislature. [67]: PDF p. 30 Under the terms of the contest, one winner and three runners-up would be selected in May 1858. [67]: PDF p. 30 [75] [79]

Greensward Plan

Park superintendent Olmsted worked with Calvert Vaux, a friend of Downing's, to create the "Greensward Plan". Olmsted and Vaux's plan was confirmed as the winner by a seven-to-four vote—mostly along party lines, as six Republicans and one Democrat had voted for the Greensward Plan. [80] [79] [81] The three runners-up were given a monetary award and featured in a city exhibit. [82] [79] [note 1] In voting for the designs, the park commissioners considered each plan's aesthetic effect, as well as the expertise of the people who proposed them. There was a minor controversy over Olmsted and Vaux's close ties to the park's Republican commissioners, as well as the fact that the Greensward Plan was the last to be submitted. [79]

The Greensward Plan distinguished itself from many of the other designs, which effectively integrated Central Park with the surrounding city, by including four sunken roadways, which introduced clear separations between park and crosstown traffic. [75] [83] [84] The plan eschewed symmetry, instead opting for a more picturesque design that "resemble[d] a charming bit of rural landscape". [85] [86] This was reinforced by the inclusion of a variety of plants and trees. [87] The Greensward Plan was also affected by the pastoral ideals of landscaped cemeteries such as Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts and Green-Wood in Brooklyn. [83] [88] According to Olmsted, the park was "of great importance as the first real Park made in this country—a democratic development of the highest significance...", a view probably inspired by his various trips to Europe during 1850. [89] [85] [note 2] In order to satisfy the commissioners' requirements for the park, Olmsted and Vaux had to include some design features that clashed with the Greensward Plan's pastoral ideal, such as the preexisting Arsenal and the never-built garden around the present-day Conservatory Water. These features would be located on low ground, hiding them from observers at street level. [90]

The Greensward Plan outlined several landscape features and watercourses to be created in Central Park. [92] Part of the former DeVoor's Mill Stream would become the Pond, located near the park's southeast corner at Grand Army Plaza. [92] [93] The Sawkill Creek, located on the west side of Central Park near the American Museum of Natural History, would be converted into the Lake. [94] On the northwestern shore of the Lake would be two spartan features, the Cave and the Rustic Arch. [87] The opposite shore would contain the Mall, with its doubled allées of elms culminating at Bethesda Terrace and Fountain, with a composed view beyond of lake and woodland. [95] [83] [94] A flat space in the southwestern section of the park would accommodate the parade ground, now the Sheep Meadow. [60] The northern section of Central Park would host the Pool, the Loch, and Harlem Meer, adapted from a single watercourse called Montayne's Rivulet. [96] [97] Above the old Croton storage reservoir, a new Upper Reservoir would be built. [98] The radically naturalistic park design taught Americans a new sensibility in park environments and urban planning. [99] [100]

The Greensward Plan also contained some architectural features. At the southern end of the park there would be a dairy house, a "Children's Mountain", a carousel, and baseball grounds. [87] Several historic structures, such as the Arsenal and a fort called Blockhouse No. 1, were incorporated into the plan. [98] In addition, 36 bridges would be interspersed through the park, each with unique designs ranging from rugged rock spans to Neo-Gothic cast iron. [91] Many of the buildings and bridges would be designed by Vaux. [101]

Following the publication of the original plan, there was considerable debate about what features should be included or excluded, even among its supporters. A week after the winning design was announced, Charles Russell and Andrew Haswell Green proposed three modifications, including the reduction of the parade ground. [102] After the board endorsed these changes to the Greensward Plan, Robert Dillon and August Belmont proposed an additional thirteen changes; these were mostly rejected, except for a proposal for segregated pedestrian, motor, and horse paths. [102] [103] Viele was then fired, and Olmsted was appointed as architect in chief, with Vaux as his assistant. [102] [104]

Construction

Multiple people were involved in creating the final design of Central Park. While Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux were the primary designers, they were assisted by Andrew Green, as well as architect Jacob Wrey Mould, master gardener Ignaz Anton Pilat, and engineer George E. Waring, Jr.. [101] [105] Olmsted was responsible for the overall plan, while Vaux designed some of the finer details. Mould, who frequently worked with Vaux, designed the Central Park Esplanade and the Tavern on the Green restaurant building. [106] Pilat was the chief landscape architect for Central Park, and was primarily responsible with the import and placement of plants within the park. [106] [107] A "corps" of construction engineers and foremen were tasked with the measuring and constructing architectural features such as paths, roads, and buildings. The corps was managed by superintending engineer William H. Grant, a former Erie Canal assistant surveyor who was hired to fill the position of Egbert Viele. [108] [109] Waring was one of the engineers working under Grant's leadership, and was in charge of land drainage. [110] [111]

Central Park was difficult to construct because of the generally rocky and swampy landscape. [112] Around 5 million cubic feet (140,000 m3) of soil and rocks had to be transported out of the park, and more gunpowder was used to clear the area than was used at the Battle of Gettysburg during the American Civil War. [113] More than 18,500 cubic yards (14,100 m3) of topsoil were transported from Long Island and New Jersey, because the original soil was neither fertile nor sufficiently substantial to sustain the flora specified in the Greensward Plan. [112] [113] Over four million trees, shrubs, and plants representing approximately 1,500 species were planted or imported to the park. [113] To provide the park's flora, Pilat managed two plant nurseries within the park boundaries: one near the Arsenal, as well as the present site of Conservatory Garden. [114] Modern steam-powered equipment and custom tree-moving machines augmented the work of unskilled laborers. [113] In total, over 20,000 individuals helped construct Central Park. [113]

1856-1858: hiring and preparatory work

Labor force

In late August 1857, workers began building fences, clearing vegetation, draining the land, and leveling uneven terrain. [67]: PDF pp. 31–35 [65] Twenty-six gangs of 15 to 20 laborers worked on removing existing plants and small boulders. Much of the existing vegetation was covered with poison ivy, and though the workers took precautions to avoid it, one gang of laborers working near 79th Street became infected with disease and stopped working. [65] Viele was allowed to hire up to 650 workers, [115] but by the following month, chief engineer Viele reported that the project employed nearly 700 workers. [67]: PDF pp. 31–35 That November, two thousand laborers organized protests in Tompkins Square Park, City Hall Park, and outside of Olmsted's offices, demanding to be hired. [116] [115] The Central Park commissioners subsequently passed a resolution to hire 1,500 to 2,000 unemployed men to work at Central Park. [117] [65]

Within the board of commissioners, there were disputes about how the workers should be employed. The Democratic minority wanted to contract the work out to private unions, as had been done with similar projects in the past, though the Republican majority found this to be inefficient. Meanwhile, the Republicans wanted to try the new method of day labor, hiring men directly without any contracts and paying them by the day. Olmsted supported the Republican proposal, and in August 1858, the commissioners gave him permission to hire day laborers on a trial basis. [118] This resulted in the hiring of the engineering "corps" that would build Central Park. [108]

The corps was somewhat successful in reforming the labor force of Central Park, but the corps still maintained a "managerial hierarchy" that sometimes led to bureaucratic delays. [108] Many of the laborers were Irish immigrants or first-or-second generation Irish Americans, though there were some Germans and Italians as well. [119] Because of the discrimination at the time, there were no black or female laborers. [120] [121] Since three-fourths of Central Park's construction budget would be spent on labor, several stringent policies were enacted to ensure that laborers were properly accounted for, such as twice-daily attendance roll calls and anti- bribery rules. [119] Throughout the course of the project, hundreds of workers were fired for "inefficiency" or for rule violations. [122] The workers were underpaid: they were promised a daily wage of $1.25 for ten hours' work when they were hired in August 1857, [121] but by the end of 1857, were only being paid $1 per day. [123] As a result, workers would often take jobs at other construction projects to supplement their salary. [122] A pattern of worker hiring was established by mid-1858. More workers would be hired from May to August, and were paid at higher rates, while workers would be fired from October to December, and those who stayed on were paid less. [121] It was only in the 1870s that the workers' daily wages would be raised to $2. [124] [125]

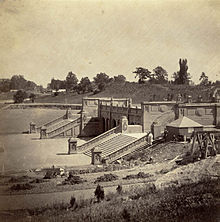

For several months, park commissioners faced delays and resistance from the New York City common council while attempting to gain funding. Furthermore, no one was willing to purchase the Central Park commission's bond issues that were supposed to pay for the park's construction. [68]: 477 [115] A dispute over appropriations temporarily halted work in September 1857, but by November, another 2,000 workers had been hired. [65] A dedicated work force and funding stream was not secured until June 1858. [68]: 477 The Upper Reservoir was the only part of the park that the commissioners were not responsible for constructing; instead, the Reservoir would be built by the Croton Aqueduct board. Work on the Reservoir started in April 1858. [126]

Regulations

Olmsted believed that many New Yorkers were "ignorant of a park, properly so-called", and had to be "trained" in the differences between Central Park and other city parks. Likewise, Vaux also wanted to distinguish Central Park from other public spaces, which he said had been ceded to "sharpers and rowdies". [127] By 1858, Olmsted hired several dozen mounted police officers, which were referred to as "keepers". [112] [125] [128] There were two classes: park keepers and gate keepers. [129]: 20–21 (PDF pp. 19–20) The mounted police were viewed favorably by park patrons, and were later incorporated into a permanent patrol. [112]

The regulations themselves were sometimes strict as a result of lobbying from religious and other organizations. [125] [130] For instance, an 1865 bill placed restrictions on fire apparatus, hearses, fire-lighting, and walking off paths. [131] Other prohibited actions included games of chance, speech-making, large congregations such as picnics, or picking flowers or other parts of plants, [125] [132] [133] as well as using "indecent language" and selling merchandise without licenses. [134] [133] To discourage park patrons from speeding, the designers incorporated extensive curves in the proposed park drives, [134] [135] though speed limits and vehicle bans were also enacted. [134] Despite the growth of sports teams in the city during the 1860s, the Central Park commissioners even refused to build facilities for sports clubs, for fear that it would "deface" or "injure" the ambiance of the park. [136] These rules applied to individuals of all social classes, and in 1859, the first year that these regulations were enforced, 228 arrests were made out of more than 2 million visitors that year. [128] However, these regulations were effective, as crime within Central Park remained generally low in contrast to the rest of the city, and the effect eventually spread to the park's borders as well. [137] By 1866, there were nearly eight million visits to the park and only 110 arrests. [138]

1858-1860: initial section

The first major work in Central Park involved grading the driveways and draining the land in the park's southern section. [139] [140] The land draining occurred during mid-1858, when George Waring directed 400 laborers to excavate trenches and line them with clay "drain tiles", as well as build large silt basins to collect the sediment that had been drained from the swamps. [110] [111] Four other division engineers led blasting, grading, and trenching, and in many cases, flattened or smoothed the existing topography to create features such as the Central Park Mall and Sheep Meadow. [110] "Rock gangs" were given the duty of blasting rock features, [140] [141] and because of extreme precautions taken to minimize collateral damage, only five laborers out of 20,000 died during the entire construction process. [141] The Central Park construction project also employed artisans such as stonecutters and blacksmiths, which made up about a fifth of the total workforce. [142]

The work included constructing carriage drives and pedestrian and bridle paths, [139] [140] These paths were graded in 1858 and paved afterward. [141] The transverse roadways were harder to construct, as they were to run below the rest of the park, but engineer J. H. Pieper devised several designs for bridges and retaining walls for each roadway. [143] In addition, several gardeners under Pilat's leadership were hired to curate and maintain different "sectors" of the park. [144] There were sometimes conflicts between the engineers, who wanted to construct the park to its original specifications without spending too much, and the gardeners, who felt it was solely their job to beautify the park, and without regard to expense. [107]

By November 1858, several miles of paths and the Mall were nearly complete, [139] [140] and the number of workers had grown to 2,600. [140] The Lake in Central Park's southwestern section was among the first features to be completed, [140] [145] partially due to the fact that it was being filled from eater that was drained from the adjacent Ramble. [110] It opened to the public as an ice skating ground that December. [145] The Ramble, the second section of the park to be completed, formally opened in June 1859. [141] [146]: 10 (PDF p. 11) The number of workers peaked at 3,600 in September of that year. [65] The same year, the New York State Legislature authorized the purchase of an additional 65 acres (260,000 m2) at the northern end of Central Park, from 106th to 110th Streets. [146]: 23 (PDF p. 25) [145] Some of the land in the park's southern section was reserved for the future construction of the Central Park Zoo and a botanical garden at what is now Conservatory Water. [147]

The southern section of Central Park below 79th Street was mostly completed by 1860, [147] and the Croton Aqueduct board also started filling in the Reservoir around this time. [126] Because park commissioner John Butterworth was dissatisfied with the slow pace of construction of the 79th Street transverse—which passed under Vista Rock, Central Park's highest point—he ordered a railroad contractor to dig the transverse. [143] At the end of that year, the Central Park commission reported that the 66th and 79th Street transverses were both completed, as well as several bridges, and that the Pond had also been filled. [148]: 5, 7 (PDF pp. 6, 8) The builders had incurred large expenses the previous year, due to the high quality of the paths and roads being constructed, but costs went down after Olmsted purchased several machines to break stone. [143] However, there were other expensive features, including the ornately designed spans Vaux had designed for Central Park. [149] In June 1860, the park commissioners reported that $4 million had been spent on the construction to date. [150] As a result of the sharply rising costs of construction, the commissioners eliminated or downsized several features in the Greensward Plan. [151]

Meanwhile, supporters of the failed Jones's Wood proposal made a final attempt to block the plans for Central Park. In 1860, they called for an investigation into the park's operations based on what they described as "malfeasance". [152] [103] Based on the Jones's Wood supporters' claims that the Central Park commission was mismanaging its costs, the New York State Senate commissioned the Swiss engineer Julius Kellersberger to write a report on the park. [153] Kellersberger's report, submitted in 1861, stated that the commission's management of the park was a "triumphant success". [152] [103]

While the investigation was ongoing, Olmsted became increasingly frustrated with the board's lack of willingness to let him administer the park independently. [154] Olmsted had a "mercurial" personality, [106] and on several occasions, he clashed with the park commissioners, notably with chief commissioner Green. In late 1859, Green arranged for Olmsted to take a three-month "working vacation" in Europe. [155] [151] Upon his return, Olmsted felt that he had been "persecuted" by Green, and in January 1861, he submitted the first of what would become five resignations. [154] [156] Because there was no funding and no suitable person to fill the chief architect's position, the commission was loath to fire Olmsted. [154] Olmsted attempted to resign in April 1861, [156] and was allowed to do so in June, when new funding was secured. [154] Green was appointed to Olmsted's position. [54] [154] Vaux would also resign by early 1863 because of what he saw as pressure from Green. [157]

1861-1865: American Civil War

When the American Civil War started in 1861. the park commissioners decided to continue building Central Park, since significant parts of the park had already been built. [158] As superintendent of the park, Green accelerated construction, despite having little experience in architecture. [54] He implemented a style of micromanagement, keeping records of the smallest transactions in an effort to reduce costs. [155] [159] This, combined with low wages, led laborers to strike for higher pay several times, including in 1862 and in 1867. [120] [159] Green also finalized the negotiations to purchase the northernmost 65 acres of the park, which was later converted into a "rugged" woodland and the Harlem Meer lake. [54] [160]

By the end of 1861, the Central Park commissioners reported that several additional bridges had been completed, and a system of water pipes had been finished and connected to the Croton Aqueduct system. [161]: 11 (PDF p. 13) [162] Bethesda Terrace was also mostly completed and sewers were being laid. An additional 2 miles (3.2 km) of carriage drives had opened, bringing the total length of open carriage ways to 7 miles (11 km); this encompassed most of the roads below 102nd Street. [161]: 12–13 (PDF pp. 14–16) [162] The park south of 72nd Street had been completed, except for various fences. [161]: 16 (PDF p. 19) The remaining carriage drives below 102nd Street were finished in 1862, though that year's expenditures decreased greatly compared to the previous year. [163]: 10 (PDF p. 11) That year also saw the start of construction on the Pool, and the completion of Conservatory Water. [163]: 14 (PDF p. 16) Additionally, 60 acres (24 ha) were set aside for the construction of a future "zoological and botanical garden", later the Central Park Zoo. [163]: 15 (PDF p. 17) [164] The Upper Reservoir was also completed in 1862. [165]

The park's commissioners assigned a name to each of the original 18 gates in 1862, representing the broad diversity of New York City's trades. [166] [167] Olmsted and Vaux opposed Richard Morris Hunt's proposal to construct ornate, European-style entrances in Central Park, since they believed the park should be available to everyone, [166] [168] [167] though they did agree to build a low stone wall around the park. [168] The builders encountered issues while attempting to construct the park's boundary wall. By 1863, there were several gaps in the wall because the surrounding streets had not been graded, which precluded the construction of a wall of consistent height. [169]: 15–16 (PDF pp. 17–18) Construction of other features was progressing steadily, and the following year, Central Park's commissioners reported that 9 miles (14 km) of carriage drives had been finished, Bethesda Terrace was essentially completed, and the Harlem Meer was being excavated. Work in the northeast section of the park was complicated by a need to preserve the historic McGowan's Pass. [170]: 7–8 (PDF pp. 9–10)

Only two major structures besides the Bethesda Terrace were completed during the Civil War: the Music Stand and the Casino restaurant, both demolished. [171] Another proposed building, a "flower house" designed by Vaux, was never built. [171] An act of the state legislature in 1864 allowed the commission to take over Manhattan Square, a plot on the western side of Central Park now occupied by the American Museum of Natural History. [170]: 13 (PDF p. 16) Another act of the legislature, a museum at the Arsenal, was never fulfilled. [172]

During this period Central Park started to gain popularity. [158] The park was already seeing 2.5 million visitors per year in 1860, and this number would more than triple over the next ten years. [173] Park patronage grew steadily and by 1864, there were 2.3 million pedestrians, 100,000 horses, and 468,000 vehicles entering Central Park in a single year. [174] About four hundred animals had been collected for the proposed zoo by 1864. [164] Despite the park's growing popularity, the park commissioners were loath to allow such events as military practices and picnics. [175] The committee instituted a ban on military parades in the Parade Ground in 1865, [175] [176] and created a strict licensing system to limit the number of refreshment shops. [177] Due to objections from religious organizations, [177] [178] boat rentals, music, and beer sales were banned on Sundays, the busiest day of the week. [177]

1866-1869: substantial progress

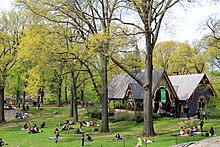

Olmsted and Vaux were re-hired to their positions in mid-1865, by which time they were jointly working on Prospect Park in Brooklyn. [179] Several structures were erected in Central Park, including the Children's District, the original Ballplayers House, and the Dairy in the southern part of Central Park. Belvedere Castle, Harlem Meer, and structures on Conservatory Water and the Lake also commenced construction. [171] [180]

Harlem Meer and the adjacent Loch, in the park's northeastern corner, were completed by 1867. In the same region, the grounds of College of Mount Saint Vincent had been improved. [181]: 10 (PDF p. 9) The following year, workers mainly proceeded on constructing Belvedere Castle, completing the Terrace's iron ceiling, and building rustic shelters and the perimeter wall. [182]: 7 (PDF p. 6)

By 1867, Central Park accommodated nearly 3 million pedestrians, 85,000 horses, and 1.38 million vehicles annually. [158] The park had activities for New Yorkers of all social classes. [183] [184] Most of the earlier visitors were wealthy: though only 5% of city residents were rich enough to afford carriages, more than half of the park's visitors arrived via carriage. [185] [186] Because most of the carriage-riders arrived mainly during the late afternoons. [185] one of the main attractions in the park's early years was the introduction of the "Carriage Parade", a daily display of horse-drawn carriages that traversed the park. [158] [187] [188] [189] Horseback riders, who comprised a smaller proportion of park visitors, were also generally wealthy. [190] A smaller middle class visited the park for activities such as walking, picnicking, or rowing. [184] The working-class was mostly unable to come to Central Park in the park's early years because it was too far from the working-class enclaves of Lower Manhattan, which could be an hour away in each direction. [186] [191]

There were other activities where both the middle and upper classes were able to participate. For instance, the weekend concerts hosted in the Mall drew tens of thousands of visitors. [184] Ice skating, once popularized in ponds downtown that had long since been filled, was one of the only activities that men and women could do separately. [192] It brought 75,000 to 100,000 visitors on an average winter day, about 30,000 more than during the rest of the year. [193] By the mid-1860s, there were separate skating ponds for women and the wealthy, and artificial rinks later supplanted skating on the ponds. [193] [192] However, for the most part, the early design of the park encouraged exercise and "individual recreation" over team sports and games. It was only in the late 1860s that the Central Park commissioners allowed well-behaved elementary school students to play sports in Central Park on a limited basis. [136]

1870-1876: completion

The Tammany Hall political machine, which was the largest political force in New York at the time, was in control of Central Park for a brief period beginning in 1870. [194] [132] On April 20 of that year, William M. Tweed, the leader of Tammany Hall, introduced a new charter that abolished the old 11-member commission and replaced it with a five-man commission composed of Green and four other Tammany-connected figures. [194] [195] [132] The Tammany commission had a much broader scope than its predecessor, providing many opportunities for corruption. The board mostly ignored Olmsted and Vaux's advice, leading both to resign from the project again in November 1870. [194] [196] [127]

The Tammany commission built pedestrian crosswalks, straightened paths, relocated trees to other parks, and destroyed or pruned vegetation, all of which were contrary to the "natural" character envisioned by Olmsted and Vaux. [197] [124] However, they also completed several features that were already under construction, such as the Carousel, Dairy, and Terrace, as well as maintained heavily-used carriage drives that had been worn down. [58] After Tweed's embezzlement was publicly revealed in 1871, leading to his imprisonment, the Central Park commission appointed new members. [124] [196] [197] Olmsted and Vaux were also reinstated as park superintendents by late 1871 or early 1872, [196] [127] though their partnership was dissolved by the end of 1872. [198] By then, Green had been appointed as New York City Comptroller, [124] [197] and he ordered a sweeping audit of all bills incurred by the Tammany commission. [199]

One of the areas that remained relatively underdeveloped was the western side of Central Park, though some large structures would be erected in the park's remaining empty plots. [200] By 1872, Manhattan Square had been reserved for the Museum of Natural History. [200] [201] A corresponding area on the East Side, originally intended as a playground, became the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1870. [200] [201] [172] Many other non-natural "encroachments" in Central Park were also proposed during this time, including some proposed by the Tammany commission. [124] These proposals, none of which were successful, included a steeplechase course, a streetcar system, houses of worship, and a miniature model of North America. [201] Smaller "encroachments" included the dozens of sculptures and memorials in Central Park, which were not part of the Greensward Plan, but nevertheless included to placate wealthy donors when appreciation of art increased in the late 19th century. [202] [203] [204] Vaux and Mould had proposed 26 statues in the Terrace in 1862, but they were eliminated because these were too expensive, and the angel in the Bethesda Fountain was the only statue included in the original park design. [204]

In the final years of Central Park's construction, Vaux and Mould designed several structures for Central Park. The Tavern on the Green and Ladies' Meadow were designed by Mould in 1870-1871, followed by the administrative offices on the 86th Street transverse in 1872, and the boathouse on the Lake in 1873. [205] The Bethesda Fountain, under construction since the early 1860s, was officially completed in 1873. [206] By that time, Tammany Hall had regained power and reorganized the Central Park board of commissioners. [197] [199] The commissioners' terms were limited to five years, [199] and in 1874, the number of commissioners was reduced to four. [68]: 474 [197] [199] The leadership of Tammany Hall would not permit Olmsted to supervise the park's force of horseback "keepers", which Olmsted believed was causing a decline in decorum within Central Park. This drove Olmsted to submit another resignation in September 1873, before withdrawing it based on the recommendation of the commission's president, a close friend. [207] [208] The park was officially completed by 1876, [207] and Andrew Green was ousted as the New York City comptroller that year. [208] Olmsted was ousted as superintendent during a vacation in December 1877. [208] [198]

Late 19th and early 20th centuries: First decline

Late 19th century: easement of rules

Upscale districts grew on both sides of Central Park following its completion, though development was stifled somewhat by the Panic of 1873. [209] The Upper East Side gradually grew in population [209] [210] and the portion of Fifth Avenue abutting lower Central Park became known as "Millionaires' Row" by the 1890s, due to the concentration of wealthy families in the area. [209] [211] The Upper West Side took longer to redevelop, and lower-class shanties and row houses coexisted with luxury apartment buildings. [209] Development increased in the 1870s due to the proximity of elevated railway stations. Row houses and luxury buildings came to predominate the Upper West Side, and some were later included in the Central Park West Historic District. [209] [212] Though most of the city's rich formerly lived in mansions, they moved into apartments close to Central Park during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Skyscrapers soon lined Central Park's perimeter, and the park's own success undermined its rural character. [213]

The park's patronage increasingly came to include the middle and working class. Strict regulations, such as those against public gatherings, were gradually eased. [186] [130] Though certain sports such as lacrosse, tennis, American football, and roller skating were allowed, the commissioners were still reluctant to repeal the "keep-off-the-grass" rules. [214] In addition, several amusement rides and refreshment concessions were opened to satisfy visitor demand. By the early 1870s, Central Park offered among other things, boat, carriage, and wheelchair rides; goat cart, donkey, and pony rides; a carousel; a photo booth; and four refreshment stands. [215]

These changes came at a cost: because of the heightened visitor count, neglect from the Tammany administration, and budget cuts demanded by taxpayers, the maintenance expense for Central Park had reached a nadir by 1879. [132] [216] Olmsted blamed three major groups for the park's decline: politicians who interfered with the original plans, real estate owners who took advantage of Central Park's proximity to suggest improvements, and park workers who abdicated their duties. However, Central Park was generally expensive to maintain, so the reduction of the budget was a major factor in the park's subsequent decline. [217] Olmsted also complained that the working and middle class visitors were not as respectful of the park regulations, performing such transgressions as breaking flowers, playing on the grass, or illicit sexual behavior. [218] The homeless people and prostitutes within Central Park were generally less numerous and less aggressive than those elsewhere in the city, though they were the most prone to arrest by the park's police. [219]

Central Park's commission became increasingly fractured and politicized in the 1880s, due to the term limits placed on the commissioners' offices and the varying demands of interested parties. [220] Political disagreements meant that park workers continued to be underpaid through at least the early 20th century, and their wages would not be increased to $5 per day until 1919. [221] At the same time, landowners did not face much difficulty being appointed to the commission: even Egbert Viele. whose initial proposal for Central Park had been rejected, became a commissioner. [220] The late 19th century saw the appointment of landscape architect Samuel Parsons to the position of parks superintendent. [202] Parsons, a onetime apprentice of Calvert Vaux, [222] [202] helped restore the nurseries of Central Park in 1886. [223] Parsons closely followed Olmsted's original vision for the park, restoring Central Park's trees while blocking the placement of several large statues in the park. [222] [224] A coalition of uptown residents and landowners pressured the commission to finish the northern part of Central Park. [225] [226] Under Parsons's leadership, two circles (now Duke Ellington and Frederick Douglass Circles) were constructed at the northern corners of the park. [227] [228]

By the 1890s, cars were becoming commonplace, bringing pollution with them, and Central Park was increasingly used for recreation rather than respite. [229] [228] Maintenance had decreased to the point where the 86th Street transverse handled most crosstown traffic because the other transverse roads had been so poorly maintained. Drainage was a particularly acute problem because the drainage pipes had degraded, and because of concerns about malaria, some ponds were filled in with asphalt and concrete. [228] In addition, the carriage roads were widened, and three new entrances were created in the park's southwestern corner. [228] A race track in Central Park, approved in 1892 over Olmsted's strong objections, was only repealed after large public backlash to the act. [230] [229] Other proposals included covering over the Upper Reservoir, proposed in 1903. [231]

Early 20th century

The entire organization of the Central Park commission was reorganized with the unification of New York City's boroughs in 1898. The commission now included three members: one each from the Bronx; Brooklyn or Queens; and Manhattan or Staten Island. [232] After the opening of the New York City Subway in 1904, which allowed New Yorkers to travel to Coney Island beaches or Broadway theaters for five cents, and Central Park was no longer the predominant attraction in New York City. [233] Recreational uses were slow to come to the park, especially since by 1914, only nine percent of the parkland was devoted to sports uses. [234] Still, the two museums, the zoo, concerts, and exhibitions in Central Park drew millions of visitors each year. [235]

Parsons was removed in May 1911 following a lengthy dispute over whether an expense to resoil the park was unnecessary. [224] [236] A succession of Tammany-affiliated Democratic mayors were indifferent toward Central Park, [237] though mayor Jimmy Walker frequented the Casino as a nighttime party destination. [238]

Several park advocacy groups were formed in the early 20th century. The citywide Parks and Playground Association, as well as a consortium of multiple Central Park civic groups operating under the Parks Conservation Association, were formed in the 1900s and 1910s to preserve the park's character. [239] The associations advocated against such changes as the construction of a library, [240] a sports stadium, [241] a cultural center, [242] and an underground parking lot in Central Park. [243] A third group. the Central Park Association, was created in 1926. [239] The Central Park Association and the Parks and Playgrounds Association were merged into the Park Association of New York City two years later. [244] Since then, at least seven different organizations have been formed with the aim of improving Central Park. [239]

The Heckscher Playground opened near the southern end of Central Park in 1926, and quickly became popular with poor immigrant families. [245] [246] At the opening of his namesake playground, philanthropist August Heckscher announced that he would start a program to raise $3 million for Central Park improvements. [246] The following year, mayor Walker commissioned Herman W. Merkel, a landscape designer to create a plan to improve Central Park. [237] Merkel's plans would combat vandalism and plant destruction, as well as rehabilitate paths and add eight new playgrounds, at a cost of $1 million. [247] [248]: 6–7 (PDF pp. 5–6) Some $140,000 had already been allocated to improvements by late 1927, [248]: 6 (PDF p. 5) and the New York City Board of Estimate appropriated another $871,000 in January 1928. [249] One of the suggested modifications, underground irrigation pipes, was installed soon after Merkel's report was submitted. [237] [250] The other improvements outlined in the report, such as fences to mitigate plant destruction, were postponed due to the Great Depression. [251]

-

Lower end of mall in 1901

-

Skating in Central Park, a movie by Frank S. Armitage, American Mutoscope and Biograph, 1900. Collection of EYE Film Institute Netherlands.

-

Brooklyn Museum collection: "Early Spring Afternoon – Central Park" (1911) by Willard Leroy Metcalf

Mid-20th century

1930s: Moses rehabilitation

In 1934, Republican Fiorello La Guardia was elected mayor of New York City, and he unified the five park-related departments then in existence. Newly appointed city parks commissioner Robert Moses was given the task of cleaning up the park, and he summarily fired many of the Tammany-era staff. [252] At the time, the lawns were filled with weeds and dust patches, while many trees were dying or already dead. Monuments were vandalized, equipment and walkways were broken, and ironwork was rusted. [252] [253]: 334 Moses biographer Robert Caro later said, "The once beautiful Mall looked like a scene of a wild party the morning after. Benches lay on their backs, their legs jabbing at the sky..." [253]: 334

During the following year, the city's parks department replanted lawns and flowers, replaced dead trees and bushes, sandblasted walls, repaired roads and bridges, and restored statues. [254] [255] [256] The park menagerie and Arsenal was transformed into the modern Central Park Zoo, and a rat extermination program was instituted there. [255] [256] Another dramatic change was Moses's removal of the " Hoover valley" shantytown at the north end of Turtle Pond, which became the 30-acre (12 ha) Great Lawn. [254] [256] The western part of the Pond at the park's southeast corner became an ice skating rink called Wollman Rink, [255] roads were improved or widened, [253]: 984 and twenty-one playgrounds were added. [256] Moses also destroyed the greenhouses at the northeast corner of the park, which he deemed obsolete, [257] and built the Conservatory Garden on the site. [258] These projects were paid for using funds from the New Deal program, as well as donations from the public. [259]

To make way for the Tavern on the Green restaurant, Moses evicted the sheep from Sheep Meadow. [253]: 984 [260] [255] The sheep were moved to Prospect Park in Brooklyn and soon thereafter moved to a farm near Otisville, New York, in the Catskill Mountains. [261]

1940s and 1950s

The 1940s and 1950s saw additional renovations. These included a restoration of the Harlem Meer completed in 1943, [262] as well as a new boathouse completed in 1954. [263] [264] [265] Moses also started constructing several other recreational features in Central Park, such as playgrounds and ballfields. [266]

One of the more controversial projects proposed during this time was a 1956 dispute over a parking lot for Tavern in the Green. The controversy placed Moses, an urban planner known for displacing families for other large projects around the city, against a group of mothers who frequented a wooded hollow at the site of a parking lot. [266] [267] Despite opposition from the parents, Moses approved the destruction of part of the hollow. Demolition work commenced after Central Park was closed for the night, and was only halted after a threat of a lawsuit. [266] [268]

Late 20th century: "Events Era" and second decline

1960s: Moses's departure

Moses left his position in May 1960. No park commissioner since Moses had been able to exercise the same degree of power, nor did NYC Parks remain as stable a position in the aftermath of his departure, with eight commissioners holding the office in the twenty years following. [269] The city was experiencing economic and social changes, with some residents leaving the city and moving to the suburbs. [270] [271] Interest in the landscape of Central Park had long since declined, and the park was now mostly being used for recreation. [272] Several unrealized additions were proposed for Central Park in that decade, such as a public housing development, [273] a golf course, [274] and a "revolving world's fair". [275] One successful addition was a new playground, which was built in 1973 as part of the construction of the 63rd Street subway lines beneath the park's southern corner. [276] The surrounding area was then re-landscaped. [277]

The 1960s also marked the beginning of an "Events Era" in Central Park that reflected the widespread cultural and political trends of the period. [278] The Public Theater's annual Shakespeare in the Park festival was settled in the Delacorte Theater upon the Delacorte's completion in 1961, [279] and summer performances were instituted on the Sheep Meadow, and then on the Great Lawn by the New York Philharmonic Orchestra and the Metropolitan Opera. [280] During the late 1960s, the park became the venue for rallies and cultural events such as the "love-ins" and "be-ins" of the period. [281] [282] Additionally, in 1966, Mayor John Lindsay, an avid cyclist, initiated a weekend ban on automobiles in Central Park for the enjoyment of cyclists and public alike. [283] The same year, Lasker Rink opened in the northern part of the park; the facility served as an ice rink in winter and Central Park's only swimming pool in summer. [284]

1970s: Neglect and reorganization

Through the 1970s, the park became a venue for events of unprecedented scale, including rallies, demonstrations, festivals, and concerts. [281] However, managerial neglect was taking a toll on the park's condition, and the frequent festivals and concerts in Central Park were later identified as part of the cause for the park's subsequent deterioration. [285] "Years of poor management and inadequate maintenance had turned a masterpiece of landscape architecture into a virtual dustbowl by day and a danger zone by night", said Douglas Blonsky, a president of the Central Park Conservancy. [286] Vandalism, territorial use (which commandeered open space and excluded other uses), and illicit activities were taking place in the park. [270] In a 1973 report, Parks, Recreation and Cultural Affairs administrator Richard Clurman cited that the park suffered from severe erosion and tree decay, and that individual structures were being vandalized or neglected. He estimated that about $2 to $6 million would need to be spent over five years to restore the park. [287] In response, a tree management program was implemented in late 1974, [288] and a "director of preservation and restoration" and a "full-time manager" for the park were appointed. [289] The same year, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission voted to grant scenic-landmark status to the park. [290]

In late 1974, Columbia University Professor E.S. Savas published a report, which concluded that the park needed one unpaid individual employed by NYC Parks to oversee its daily operations. It also recommended the establishment of a private, citizen-based board that would advise the overseeing individuals, as well as the creation of the Central Park Community Fund. [291] [292] The Fund was subsequently founded by Richard Gilder and George Soros that year, [293] [294] followed by the Central Park Task Force, an agency of NYC Parks, the following year. [294] In January 1975, a $4 million plan to renovate Wollman Rink at the park's southeastern corner was announced. [295] However, this plan was rejected by the NYC Parks officials as being "unimaginative". [296] By late 1975, the Central Park Task Force released a revised plan to renovate the Pond and Wollman Rink at the park's southwestern corner for $2.5 million. [296]

The Community Fund commissioned a study of the park's management, which was released in 1978. The study's conclusion was bi-linear; it called for establishment of a single position within the New York City Parks Department, responsible for overseeing both the planning and management of Central Park, as well as a board of guardians to provide citizen oversight. [270] [297] In 1979, Parks Commissioner Gordon Davis established the Office of Central Park Administrator and appointed Elizabeth Barlow, the executive director of the Central Park Task Force, to the position. [270] [298] [285] The Central Park Conservancy, a nonprofit organization with a citizen board, was founded the following year. [270] [299] [300] Mayor Ed Koch selected William Sperry Beinecke as the inaugural chair of the board of the Central Park Conservancy; Beinecke then was charged with selecting the board's roughly thirty private citizens. [301] [292] Meanwhile, the New York Zoological Society signed an agreement with the city to take over the Central Park Zoo, and real estate developer Donald Trump signed a similar agreement to take control of Wollman Rink. [302]

1970s to 2000s: restoration

Under the leadership of the Central Park Conservancy, the park's reclamation began with modest but highly significant first steps, addressing needs that could not be met within the existing structure and resources of the parks department. Interns were hired and a small restoration staff to reconstruct and repair unique rustic features, undertaking horticultural projects, and removing graffiti under the broken windows theory. [270] [303]

1980s–90s renovations

The first structure to be renovated was the Dairy, which was completely rehabilitated and reopened as the park's first visitor center in 1979. [304] The Sheep Meadow, which reopened the following year, was the first landscape to be restored. [305] By then, the Conservancy was engaged in design efforts and long-term restoration planning. [306] Some projects were already underway or complete. Bethesda Fountain, which had been dry for decades, was restored in 1981; [307] the USS Maine National Monument and the Bow Bridge had also already been restored. [308] At the end of 1981, Davis and Barlow announced a 10-year, $100 million "Central Park Management and Restoration Plan", under which all future renovations would proceed. [308]

The first project to be undertaken as part of the restoration plan was the renovation of Bethesda Terrace, which started in 1982-1983. [309] [310] The long-closed Belvedere Castle was renovated and reopened around this time, [309] [311]: 29 and the renovation won an award from the Landmarks Preservation Commission. [312] [313] The Central Park Zoo was then closed for renovation in 1983. [314] [285] The renovation of Central Park also entailed the examinations of thousands of plants, as well as the mapping and construction of new paths along heavily-trafficked grass routes. [285] In conjunction with this renovation, the Strawberry Fields memorial to the murdered musician John Lennon was also built in the western end of the park, [315] and the Dene Rustic Shelter was restored. [316] In an effort to reduce the maintenance effort for Central Park, certain large gatherings such as free concerts were banned within Central Park. [317]

On completion of the planning stage in 1985, the conservancy launched its first capital campaign, assuming increasing responsibility for funding the park's restoration, and full responsibility for designing, bidding, and supervising all capital projects in the park. [270] The Conservancy mapped out a 15-year restoration plan that sought to remain true to the original design. [318] Over the next several years, the campaign restored landmarks in the southern part of the park, such as Grand Army Plaza [319] and the police station at the 86th Street transverse, [320] while Conservatory Garden in the northern part of the park was restored to a design by Lynden B. Miller. [321] [322] [323] Trump renovated the Wollman Rink in 1987 after plans to renovate the rink were repeatedly delayed. [324] The following year, the Zoo reopened after a $35 million renovation. [325] By 1988, the Conservancy was raising $6 million in donations annually. [326] However, the Conservancy still faced obstacles, including opposition to projects such as the reconstruction of the Mall's bandshell and the erection of a North Meadow recreation center. [327]

Improvements to the northern end of the park began in 1989. [328] and the Ravine in the northern part of the park was completed by 1992. [311]: 33 The following year, the Conservancy announced a $51 million capital campaign. [329] This resulted in the restoration of bridle trails, [330] the Mall, [311]: 22 the Harlem Meer, [331] and the North Woods, [328] as well as the construction of the Dana Discovery Center on the Harlem Meer. [331] Afterward, the Conservancy embarked on its most ambitious landscape restoration: the overhaul of the 55 acres (22 hectares) near the Great Lawn and Turtle Pond. [332] The project was the centerpiece of the Conservancy's three-year Wonder of New York Campaign, which raised $71.5 million and also helped restore southern and western landscapes, as well as the North Meadow. [333] The Great Lawn project was completed in 1997. [334] In addition, the Upper Reservoir was decommissioned as a part of the city's water supply system in 1993, [335] and was renamed after former U.S. first lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis the next year. [336]

Citywide budget cuts in the early 1990s, however, resulted in attrition of the park's routine maintenance staff, and the conservancy began hiring staff to replace these workers. Management of the restored landscapes by the conservancy's "zone gardeners" proved so successful that core maintenance and operations staff were reorganized in 1996. The zone-based system of management was implemented throughout the park, which was divided into 49 zones. [270] [286] The Conservancy assumed much of the park's operations in early 1998. [337]

2000s renovations

Renovations continued through the first decade of the 21st century. Conservatory Water was restored over six months in 2000, and the restoration of the Pond began the same year. [338] A new fence around the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Reservoir was installed in 2004 under a capital project that replaced the old chain-link fence with a replica of the 8,000-foot long steel and cast-iron one that had enclosed the Reservoir in 1926. The new fence, along with removal of invasive trees and shrubs, restored the panoramic views of the park and Manhattan skyline. [339]

Another ambitious restoration effort began in 2004, when Conservancy staff and contractors worked together to refurbish the 15,876 Minton tiles that hang on the ceiling of the Bethesda Arcade. Originally designed by Calvert Vaux and Jacob Wrey Mould, the ceiling of the Arcade is lined by 15,876 elaborately patterned encaustic tiles. Salt and water infiltration from the roadway above had badly damaged the tiles, leaving their backing plates so corroded they had to be removed in the 1980s. [307] The tiles sat in storage for more than 20 years until the Conservancy embarked on a $7 million restoration effort to return the Minton tiles to their original luster in 2004. [340] The completed Bethesda Terrace Arcade was unveiled in March 2007.

The Ramble and Lake was then renovated by the Central Park Conservancy, in a project to enhance both its ecological [note 3] and scenic aspects. In 2007 the first phase of a restoration of the Lake and its shoreline plantings commenced. [341] During the same time, Bank Rock Bridge was recreated in carved oak with cast-iron panels and pine decking, its original materials, following Vaux's original design of 1859–60. [342] [343] The cascade, where the Gill empties into the lake, was reconstructed to approximate its dramatic original form. The island formerly in the lake, which gradually eroded below water level, was replanted with aqueous plants like Pickerel weed. [344] The first renovated sections were opened to visitors in April 2008 [345] and the project was complete by 2012. [311]: 56

The final feature to be restored was the East Meadow, which was rehabilitated in 2011. [346]

2010s to present

On October 23, 2012, hedge fund manager John A. Paulson announced a $100 million gift to the Central Park Conservancy, the largest ever monetary donation to New York City's park system. [347]

Since the 1960s, there has been a grassroots campaign to restore the park's loop drives to their original car-free state. Over the years, the number of car-free hours increased, though a full closure was resisted by the New York City Department of Transportation. Legislation was proposed in October 2014 to conduct a study to make the park car-free in summer 2015. [348] In 2015, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced the permanent closure of West and East Drives north of 72nd Street to vehicular traffic as it was proven that closing the roads did not adversely impact traffic. [349] Subsequently, in June 2018, the remaining drives south of 72nd Street were closed to vehicular traffic. [350] [351]

Several renovation projects continued through the park in the late 2010s. Belvedere Castle was closed in 2018 for an extensive renovation, reopening in June 2019. [352] [353] [354] Also in 2018, it was announced that Lasker Rink would be closed for a three-year, $150 million renovation. [355] Later in 2018, it was announced that the Delacorte Theater would also be closed from 2020 to 2022 for a $110 million rebuild. [356] The Central Park Conservancy later revealed that Lasker Rink's complete reconstruction would take place between 2021 and 2024. [357] [358] [359]

In March 2020, in response to the worldwide coronavirus pandemic, temporary field hospitals were set up within the park to treat overflow patients from area hospitals. [360] [361]

(Notes that don't really fit)

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ The second-place winner was Samuel Gustin, the park's gardener. This was followed by the plans of Michael Miller and Lachland McIntosh, both Central Park clerks, and Howard Daniels, a landscape gardener in the nearby area [79] [81]

- ^ He had visited several parks during these trips and was particularly impressed by Birkenhead Park and Derby Arboretum in England. [79]

- ^ "Its increasing significance as a wildlife habitat" was noted on the Conservancy's on-site information boards.

References

- ^ a b Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, pp. 23, 25.

- ^ a b c d Kinkead 1990, pp. 11–13.

- ^ Heckscher 2008, p. 9.

- ^ Todd, John Emerson (1982). Frederick Law Olmsted. Boston: Twayne Publishers: Twayne's World Leader Series. p. 73.

- ^ "Unearthing the City Grid That Would Have Been in Central Park". The New Yorker. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- ^ Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Heckscher 2008, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Van Buren, Alex; Travel + Leisure (January 27, 2016). "12 Secrets of New York's Central Park". Smithsonian. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- ^ a b Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, pp. 15, 29–30.

- ^ Downing, Andrew (1848). "A Talk about Public Parks and Gardens". Horticulturalist, and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste.

- ^ a b c d Kinkead 1990, pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b Beard, Charles A. (May 1926). "Some Aspects of Regional Planning". American Political Science Review. 20 (2): 273–283. doi: 10.2307/1945139. ISSN 0003-0554. JSTOR 1945139.

- ^ a b c d New York (State). Legislature. Assembly (1911). Documents of the Assembly of the State of New York. pp. 451–458. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- ^ a b Taylor 2009, p. 258.

- ^ Berman 2003, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Kinkead 1990, p. 16.

- ^ a b Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, pp. 21, 40.

- ^ Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b c d Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, p. 45.

- ^ Taylor 2009, p. 259.

- ^ a b Heckscher 2008, pp. 12, 14.

- ^ "First Annual Report". Board of Commissioners of Central Park. 1851.

- ^ Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, pp. 49–50.

- ^ "James W. Beekman Papers". Jones Woods Petitions. 1853.

- ^ a b c d Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, pp. 51–53.

- ^ a b c Taylor 2009, p. 260.

- ^ "The Central Park". The New York Times. September 19, 1853. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- ^ a b c Heckscher 2008, pp. 15–16.

- ^ a b c d e Kinkead 1990, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d e Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, pp. 81–83.

- ^ Annual Report of the Comptroller of the City of New York, of the Receipts and Expenditures of the Corporation, for the Year ... 1857. p. 38. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- ^ a b Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Taylor 2009, pp. 261–262.

- ^ a b c d Heckscher 2008, p. 17.

- ^ Williams, Keith (February 7, 2018). "Uncovering the Ruins of an Early Black Settlement in New York". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- ^ Blakinger, Keri (May 17, 2016). "A look at Seneca Village, the early black settlement obliterated by the creation of Central Park". New York Daily News. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- ^ Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, pp. 65–67.

- ^ a b c Kinkead 1990, p. 18.

- ^ Rossi, Peter H. (1989). Down and Out in America: The Origins of Homelessness. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-72828-5.

- ^ Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, p. 88.

- ^ Gilligan, Heather (February 23, 2017). "An entire Manhattan village owned by black people was destroyed to build Central Park". Timeline. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- ^ a b c Heckscher 2008, p. 18.

- ^ "The Central Park--The Assessment Completed". The New York Times. October 4, 1855. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 1, 2019.

- ^

a

b

"The Central Park; The Work to be Commenced Immediately". New York Herald. June 5, 1856. p. 1. Retrieved March 30, 2019 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Beach, Frederick Converse Beach; Rines, George Edwin, eds. (1903). "Central City – Central Park". The Encyclopedia Americana. 4. The Americana Company.

- ^ a b Martin, Douglas (January 31, 1997). "A Village Dies, A Park Is Born". The New York Times.

- ^ Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, pp. 89–90.

- ^ " Seneca Village". MAAP: Mapping the African American Past. Columbia University.

- ^ a b Berman 2003, p. 19.

- ^ Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, pp. 46–47.

- ^ "Taking the Land – 1850". CentralParkHistory.com. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Andrew H. Green and Central Park". The New York Times. October 10, 1897. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- ^ Reed, Henry Hope; McGee, Robert M.; Mipaas, Esther (1990). Bridges of Central Park. Greensward Foundation. ISBN 978-0-93131-106-2.

- ^ "Treaty with Russia for the Purchase of Alaska". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on March 29, 2015. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ a b Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, pp. 85–87.

- ^ a b Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, pp. 268–269.

- ^ Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, p. 88.

- ^ a b Kinkead 1990, p. 44.

- ^ a b c Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, pp. 100–101.

- ^ a b Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Berman 2003, p. 21.

-

^

"General Egbert E. Viele". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. April 23, 1902. p. 3. Retrieved March 30, 2019 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, pp. 161–162.

- ^ a b Kinkead 1990, pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b c d e f g "1858 Central Park Commissioners Annual Report" (PDF). New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. 1858. Retrieved January 13, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e First-thirtieth Annual Report ... 1896-1925 to the Legislature of the State of New York ... Annual Report. 1911. p. 474. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- ^ "THE CENTRAL PARK.; Report of the Commissioners of the Central Park in Reply to the Inquiries of the State Senate". The New York Times. March 13, 1860. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- ^ Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, p. 155.

- ^ Kinkead 1990, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Olmsted, F.L.; Beveridge, C.E.; Schuyler, D. (1983). The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted: Creating Central Park, 1857â€"1861. The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-8018-2751-8. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- ^ a b Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, pp. 102–103.

- ^ a b Heckscher 2008, p. 20.

- ^ a b c d Kinkead 1990, pp. 24–25.

- ^ a b c Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, pp. 111–112.

- ^ "The Design Competition". CentralParkHistory.com. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ a b c Heckscher 2008, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d e f Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, pp. 117–120.

- ^ "The Central Park Plans". The New York Times. April 30, 1858. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 1, 2019.

- ^ a b Heckscher 2008, pp. 23–24.

- ^ "THE CENTRAL PARK.; Exhibition of the Unsuccessful Plans for the Central Park". The New York Times. May 13, 1858. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 1, 2019.

- ^ a b c Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, pp. 130–135.

- ^ Heckscher 2008, p. 27.

- ^ a b Scobey, David (2002). Empire city : the making and meaning of the New York City landscape. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-59213-235-5. OCLC 48222693.

- ^ Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, pp. 239–240.

- ^ a b c Kinkead 1990, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Taylor 2009, p. 266.

- ^ Taylor 2009, pp. 267–268.

- ^ Heckscher 2008, p. 28.

- ^ a b Henry Hope Reed, Robert M. McGee and Esther Mipaas. The Bridges of Central Park. (Greensward Foundation) 1990.

- ^ a b Kinkead 1990, p. 35.

- ^ Dwyer, Jim (May 11, 2017). "Tracing the Waterways Beneath the Sidewalks of New York". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- ^ a b Kinkead 1990, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Taylor 2009, pp. 264–265.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (May 26, 2011). "Scenes From a Wild Youth - Streetscapes/Central Park". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- ^ Kinkead 1990, p. 48.

- ^ a b Kinkead 1990, p. 50.

- ^ Andrew, Menard (2010). "The Enlarged Freedom of Frederick Law Olmsted". New England Quarterly. 83 (3): 508–538. doi: 10.1162/TNEQ_a_00039. JSTOR 20752715. S2CID 57567923.

- ^ Moehring, Eugene P. (1985). "Frederick Law Olmsted and the Central Park 'Revolution'". Halcyon: A Journal of the Humanities. 7 (1): 59–75.

- ^ a b Kinkead 1990, p. 51.

- ^ a b c Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, pp. 140–143.

- ^ a b c Heckscher 2008, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Kinkead 1990, p. 27.