In 2014, a study was conducted regarding the determination of the depth and location of the Challenger Deep based on data collected previous to and during the 2010 sonar mapping of the Mariana Trench with a Kongsberg Maritime EM 122 multibeam echosounder system aboard USNS Sumner. This study by James. V. Gardner et al. of the Center for Coastal & Ocean Mapping-Joint Hydrographic Center (CCOM/JHC), Chase Ocean Engineering Laboratory of the University of New Hampshire splits the measurement attempt history into three main groups: early single-beam echo sounders (1950s–1970s), early multibeam echo sounders (1980s – 21st century), and modern (i.e., post-GPS, high-resolution) multibeam echo sounders. Taking uncertainties in depth measurements and position estimation into account the raw data of the 2010 bathymetry of the Challenger Deep vicinity consisting of 2,051,371 soundings from eight survey lines was analyzed. The study concludes that with the best of 2010 multibeam echosounder technologies after the analysis a depth uncertainty of ±25 m (82 ft) (95% confidence level) on 9 degrees of freedom and a positional uncertainty of ±20 to 25 m (66 to 82 ft) ( 2drms) remain and the location of the deepest depth recorded in the 2010 mapping is 10,984 m (36,037 ft) at 11°19′48″N 142°11′57″E / 11.329903°N 142.199305°E. The depth measurement uncertainty is a composite of measured uncertainties in the spatial variations in sound-speed through the water volume, the ray-tracing and bottom-detection algorithms of the multibeam system, the accuracies and calibration of the motion sensor and navigation systems, estimates of spherical spreading, attenuation throughout the water volume, and so forth. [1]

Both the RV Sonne expedition in 2016, and the RV Sally Ride expedition in 2019 expressed strong reservations concerning the depth corrections applied by the Gardner et al. study of 2014, and serious doubt concerning the accuracy of the deepest depth calculated by Gardner (in the western basin), of 10,984 m (36,037 ft) after analysis of their multibeam data on a 100 m (328 ft) grid. Dr. Hans van Haren, chief scientist on the RV Sally Ride cruise SR1916, indicated that Gardner's calculations were 69 m (226 ft) too deep due to the "sound velocity profiling by Gardner et al. (2014)." [2]

In 2018-2019 the deepest points of each ocean were mapped using a full‐ocean depth Kongsberg EM 124 multibeam echosounder abord DSSV Pressure Drop. In 2021 a data paper was published by Cassandra Bongiovanni, Heather A. Stewart and Alan J. Jamieson regarding the gathered data donated to GEBCO. The deepest depth recorded in the 2019 Challenger Deep sonar mapping was 10,924 m (35,840 ft) ±15 m (49 ft) at 11°22′08″N 142°35′13″E / 11.369°N 142.587°E in the eastern basin. This depth closely agrees with the deepest point (10,925 m (35,843 ft) ±12 m (39 ft)) determined by the Van Haren et al. sonar bathymetry. The geodetic position of the deepest depth according to the Van Haren et al. significantly differs (about 42 km (26 mi) to the west) with the 2021 paper. After post-processing the initial depth estimates by application of a full-ocean depth sound velocity profile Bongiovanni et al. report an (almost) as deep point at 11°19′52″N 142°12′18″E / 11.331°N 142.205°E in the western basin that geodetically differs about 350 m (1,150 ft) with the deepest point position determined by Van Haren et al. ( 11°19′57″N 142°12′07″E / 11.332417°N 142.20205°E in the western basin). After analysis of their multibeam data on a 75 m (246 ft) grid the Bongiovanni et al. 2021 paper states the technological accuracy does not currently exist on low-frequency ship-mounted sonars required to determine which location was truly the deepest, nor does it currently exist on deep-sea pressure sensors. [3]

In 2021 a study by Samuel F. Greenaway, Kathryn D. Sullivan, Samuel H. Umfress, Alice B. Beittel and Karl D. Wagner was published presenting a revised estimate of the maximum depth of the Challenger Deep based on a series of submersible dives conducted in June 2020. These depth estimates are derived from acoustic echo sounding profiles referenced to in-situ direct pressure measurements and corrected for observed oceanographic properties of the water-column, atmospheric pressure, gravity and gravity-gradient anomalies, and water-level effects. The study concludes according to their calculations the deepest observed seafloor depth was 10,935 m (35,876 ft) ±6 m (20 ft) below mean sea level at a 95% condidence level at 11°22.3′N 142°35.3′E / 11.3717°N 142.5883°E in the eastern basin. For this estimate, the error term is dominated by the uncertainty of the employed pressure sensor, but Greenaway et al. show that the gravity correction is also substantial. The Greenaway et al. study compares its results with other recent acoustic and pressure-based measurements for the Challenger Deep and concluds the deepest depth in the western basin is very nearly as deep as the eastern basin. The disagreement between the maximum depth estimates and their geodetic positions between post-2000 published dephts however exceed the accompanying margins of uncertainty, raising questions ragarding the measurements or the reported uncertainties. [4]

Another 2021 paper by Scott Loranger, David Barclay and Michael Buckingham, besides an implosion shock wave based depth estimate, also treatises the differences between various maximum depth estimates and their geodetic positions. [5]

Direct measurements

The 2010 maximal sonar mapping depths reported by Gardner et.al. in 2014 have not been confirmed by subsequent direct descent (pressure gauge/manometer) measurements at full-ocean depth.

[6]

Expeditions have reported direct measured maximal depths in a narrow range.

For the western basin deepest depths were reported as 10,913 m (35,804 ft) by

Trieste in 1960 and 10,923 m (35,837 ft) ±4 m (13 ft) by

DSV Limiting Factor in June 2020.

For the central basin the greatest reported depth is 10,915 m (35,810 ft) ±4 m (13 ft) by

DSV Limiting Factor in June 2020.

For the eastern basin deepest depths were reported as 10,911 m (35,797 ft) by ROV

Kaikō in 1995, 10,902 m (35,768 ft) by

ROV Nereus in 2009, 10,908 m (35,787 ft) by

Deepsea Challenger in 2012, 10,929 m (35,856 ft) by

benthic lander "Leggo" in May 2019, and 10,925 m (35,843 ft) ±4 m (13 ft) by

DSV Limiting Factor in May 2019.

The exact location and the depth of the very deepest spot remain topics of interest to the oceanographic research community. No one has claimed that a measurement of any maximal depth of the Challenger Deep (either by direct CTD pressure measurements or by ensonification) defines either the absolute deepest depth or the geophysical location of the deepest point in the Challenger Deep. Such a claim will require a survey of all three basins by both echosounders and pressure gauges, such that all depths are measured by one set of equipment and use the same correction calculations. Even then, there will remain uncertainty (error bars) of one or two standard deviations in both location and depth. Technology will improve, but uncertainty will continue to drive efforts to fully describe the Challenger Deep.

Descents

Crewed descents

1960 – Trieste

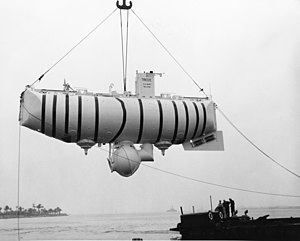

On 23 January 1960, the Swiss-designed Trieste, originally built in Italy and acquired by the U.S. Navy, supported by the USS Wandank (ATF 204) and escorted by the USS Lewis (DE 535), descended to the ocean floor in the trench manned by Jacques Piccard (who co-designed the submersible along with his father, Auguste Piccard) and USN Lieutenant Don Walsh. Their crew compartment was inside a spherical pressure vessel – measuring 2.16 metres in diameter suspended beneath a buoyancy tank 18.4 metres in length [7] – which was a heavy-duty replacement (of the Italian original) built by Krupp Steel Works of Essen, Germany. The steel walls were 12.7 cm thick and designed to withstand pressure of up to 1250 kilograms per square centimetre (1210 atm; 123 MPa). [7] Their descent took almost five hours and the two men spent barely twenty minutes on the ocean floor before undertaking the three-hour-and-fifteen-minute ascent. Their early departure from the ocean floor was due to their concern over a crack in the outer window caused by the temperature differences during their descent. [8]

Trieste dove at/near 11°18.5′N 142°15.5′E / 11.3083°N 142.2583°E, bottoming at 10,911 metres (35,797 ft) ±7 m (23 ft) into the Challenger Deep's western basin, as measured by an onboard manometer. [9] Another source states the measured depth at the bottom was measured with a manometer at 10,913 m (35,804 ft) ±5 m (16 ft). [10] [11] Navigation of the support ships was by celestial and LORAN-C with an accuracy of 460 metres (1,510 ft) or less. [12] Fisher noted that the Trieste's reported depth "agrees well with the sonic sounding." [13]

2012 – Deepsea Challenger

On 26 March 2012 (local time), Canadian film director James Cameron made a solo manned descent in the DSV Deepsea Challenger to the bottom of the Challenger Deep. [14] [15] [16] [17] At approximately 05:15 ChST on 26 March (19:15 UTC on 25 March), the descent began. [18] At 07:52 ChST (21:52 UTC), Deepsea Challenger arrived at the bottom. The descent lasted 2 hours and 36 minutes and the recorded depth was 10,908 metres (35,787 ft) when Deepsea Challenger touched down. [19] Cameron had planned to spend about six hours near the ocean floor exploring but decided to start the ascent to the surface after only 2 hours and 34 minutes. [20] The time on the bottom was shortened because a hydraulic fluid leak in the lines controlling the manipulator arm obscured the visibility out the only viewing port. It also caused the loss of the submersible's starboard thrusters. [21] At around 12:00 ChST (02:00 UTC on 26 March), the Deepsea Challenger website says the sub resurfaced after a 90-minute ascent, [22] although Paul Allen's tweets indicate the ascent took only about 67 minutes. [23] During a post-dive press conference Cameron said: "I landed on a very soft, almost gelatinous flat plain. Once I got my bearings, I drove across it for quite a distance ... and finally worked my way up the slope." The whole time, Cameron said, he didn't see any fish, or any living creatures more than an inch (2.54 cm) long: "The only free swimmers I saw were small amphipods" – shrimplike bottom-feeders. [24]

2019 – Five Deeps Expedition / DSV Limiting Factor

The Five Deeps Expedition objective was to thoroughly map and visit the deepest points of all five of the world's oceans by the end of September 2019. [25] On 28 April 2019, explorer Victor Vescovo descended to the "Eastern Pool" of the Challenger Deep in the Deep-Submergence Vehicle DSV Limiting Factor (a Triton 36000/2 model submersible). [26] [27] Between 28 April and 4 May 2019, the Limiting Factor completed four dives to the bottom of Challenger Deep. The fourth dive descended to the slightly less deep "Central Pool" of the Challenger Deep (crew: Patrick Lahey, Pilot; John Ramsay, Sub Designer). The Five Deeps Expedition estimated maximum depths of 10,927 m (35,850 ft) ±8 m (26 ft) and 10,928 m (35,853 ft) ±10.5 m (34 ft) at ( 11°22′09″N 142°35′20″E / 11.3693°N 142.5889°E) by direct CTD pressure measurements and a survey of the operating area by the support ship, the Deep Submersible Support Vessel DSSV Pressure Drop, with a Kongsberg SIMRAD EM124 multibeam echosounder system. The CTD measured pressure at 10,928 m (35,853 ft) of seawater depth was 1,126.79 bar (112.679 MPa; 16,342.7 psi). [28] [29] Due to a technical problem the (unmanned) ultra-deep-sea lander Skaff used by the Five Deeps Expedition stayed on the bottom for two and half days before it was salvaged by the Limiting Factor (crew: Patrick Lahey, Pilot; Jonathan Struwe, DNV GL Specialist) from an estimated depth of 10,927 m (35,850 ft). [30] [29] The gathered data was published with the caveat that it was subject to further analysis and could possibly be revised in the future. The data will be donated to the GEBCO Seabed 2030 initiative. [31] [27] [32] [33] [34] Later in 2019, following a review of bathymetric data, and multiple sensor recordings taken by the DSV Limiting Factor and the ultra-deep-sea landers Closp, Flere and Skaff, the Five Deeps Expedition revised the maximum depth to 10,925 m (35,843 ft) ±4 m (13 ft). [35]

2020 – Ring of Fire Expedition / DSV Limiting Factor

Caladan Oceanic's "Ring of Fire" expedition in the Pacific included six crewed descents and twenty-five lander deployments into all three basins of the Challenger Deep all piloted by Victor Vescovo and further topographical and marine life survey of the entire Challenger Deep. [36] The expedition craft used are the Deep Submersible Support Vessel DSSV Pressure Drop, Deep-Submergence Vehicle DSV Limiting Factor and the ultra-deep-sea landers Closp, Flere and Skaff. During the first crewed dive on 7 June 2020 Victor Vescovo and former US astronaut (and former NOAA Administrator) Kathryn D. Sullivan descended to the "Eastern Pool" of the Challenger Deep in the Deep-Submergence Vehicle Limiting Factor. [37] [38]

On 12 June 2020 Victor Vescovo and mountaineer and explorer Vanessa O'Brien descended to the "Eastern Pool" of the Challenger Deep spending three hours mapping the bottom. O’Brien said her dive scanned about a mile of desolate bottom terrain, finding that the surface is not flat, as once was thought, but sloping, and by about 18 ft (5.5 m), subject to verification, of course. [39] [40] [41] [42] On 14 June 2020 Victor Vescovo and John Rost descended to the "Eastern Pool" of the Challenger Deep in the Deep-Submergence Vehicle Limiting Factor spending four hours at depth and transiting the bottom for nearly 2 miles. [43] On 20 June 2020 Victor Vescovo and Kelly Walsh descended to the "Western Pool" of the Challenger Deep in the Deep-Submergence Vehicle Limiting Factor spending four hours at the bottom. They reached a maximum depth of 10,923 m (35,837 ft). Kelly Walsh is the son of the Trieste’s captain Don Walsh who descended there in 1960 with Jacques Piccard. [44] [45] On 21 June 2020 Victor Vescovo and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution researcher Ying-Tsong Lin descended to the "Central Pool" of the Challenger Deep in the Deep-Submergence Vehicle Limiting Factor. They reached a maximum depth of 10,915 m (35,810 ft) ±4 m (13 ft). [46] [47] [48] On 26 June 2020 Victor Vescovo and Jim Wigginton descended to the "Eastern Pool" of the Challenger Deep in the Deep-Submergence Vehicle Limiting Factor. [49]

- ^ "So, How Deep Is the Mariana Trench?" (PDF). Center for Coastal & Ocean Mapping-Joint Hydrographic Center (CCOM/JHC), Chase Ocean Engineering Laboratory of the University of New Hampshire. 5 March 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

-

^ Cite error: The named reference

hansvanharen.nlwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Bongiovanni, Cassandra; Stewart, Heather A.; Jamieson, Alan J. (2021-05-05). "High‐resolution multibeam sonar bathymetry of the deepest place in each ocean". Geoscience Data Journal. Royal Meteorological Society. doi: 10.1002/gdj3.122.

- ^ Greenaway, Samuel F.; Sullivan, Kathryn D.; Beittel, Alice B.; Wagner, Karl D.; Umfress, Samuel H. (2021-10-21). "Revised depth of the Challenger Deep from submersible transects; including a general method for precise, pressure-derived depths in the ocean". Oceanographic Research Papers. 178. NOAA, Potomac Institute: 103644. Bibcode: 2021DSRI..17803644G. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2021.103644.

- ^ Loranger, Scott; Berclay, David; Buckingham, Michael (2021-04-19). "Implosion in the Challenger Deep: Echo Sounding with the Shock Wave". Oceanography. 34 (2). The Oceanography Society. doi: 10.5670/oceanog.2021.201. Retrieved 2021-11-04.

- ^ "So, How Deep Is the Mariana Trench?" (PDF). Center for Coastal & Ocean Mapping-Joint Hydrographic Center (CCOM/JHC), Chase Ocean Engineering Laboratory of the University of New Hampshire. 5 March 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ^ a b Kwek, Glenda (13 April 2011). "Descent to Challenger Deep". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

-

^

"Archived copy". Archived from

the original on 14 April 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

{{ cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title ( link) - ^ Piccard, J. "Seven Miles Deep," G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1961, p. 242

-

^ Cite error: The named reference

Bathymetric mapping of the world’s deepest seafloor, Challenger Deepwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Press Release, Office of Naval Research (1 February 1960). "Research Vessels: Submersibles – Trieste". United States Navy. Archived from the original on 18 April 2002. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

-

^ Cite error: The named reference

jproc.cawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Fisher, Trenches, The Earth Beneath the Sea, p. 416

-

^ Cite error: The named reference

NGS-20120325was invoked but never defined (see the help page). -

^ Cite error: The named reference

NYT-20120325was invoked but never defined (see the help page). -

^ Cite error: The named reference

MSNBC-20120325was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Prince, Rosa (25 March 2012). "James Cameron becomes first solo diver to visit Earth's deepest point". The Telegraph. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ^ National Geographic (25 March 2012). "James Cameron Begins Descent to Ocean's Deepest Point". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ National Geographic (25 March 2012). "James Cameron Now at Ocean's Deepest Point". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ National Geographic (26 March 2012). "Cameron's Historic Dive Cut Short by Leak; Few Signs of Life Seen". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ^ National Geographic (28 March 2012). "Cameron's Historic Dive Cut Short by Leak; Few Signs of Life Seen". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ^ deepseachallenge.com (25 March 2012). "We Just Did the Impossible". deepseachallenge.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

-

^ twitter.com/PaulGAllen (27 March 2012).

"Paul Allen Tweets from Challenger Deep". twitter.com/PaulGAllen. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

{{ cite web}}:|author=has generic name ( help) - ^ National Geographic (27 March 2012). "James Cameron on Earth's Deepest Spot: Desolate, Lunar-Like". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ^ "Home". fivedeeps.com. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ "Full Ocean Depth Submersible LIMITING FACTOR". fivedeeps.com. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ^ a b "Mariana Trench: Deepest-ever sub dive finds plastic bag". BBC News. 13 May 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ "Full Ocean Depth Submersible DNV-GL CERTIFICATION". fivedeeps.com. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- ^ a b "UNESCO Technical Papers in Marine Science 44, Algorithms for computation of fundamental properties of seawater". ioc-unesco.org. 1983. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "Dive to the ultimate abyss". dnvgl.com. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ "Deepest Submarine Dive in History, Five Deeps Expedition Conquers Challenger Deep" (PDF). fivedeeps.com. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ The Nippon Foundation-GEBCO Seabed 2030 Project

- ^ "Major partnership announced between The Nippon Foundation-GEBCO Seabed 2030 Project and The Five Deeps Expedition". gebco.net. 11 March 2019. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ "Science Landers Flere, Skaff & Closp". fivedeeps.com. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- ^ "The Five Deeps Expedition Overview". fivedeeps.com. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ "The Ring of Fire Expedition Overview". caladanoceanic.com. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ "Former astronaut becomes first person to visit both space and the deepest place in the ocean". collectspace.com. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ "Astronaut Kathy Sullivan is first woman to dive to Challenger Deep". cnn.com. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ "Explorer becomes the first woman to reach the highest and lowest points on the planet". metro.co.uk. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ "Second Woman to Make Challenger Deep Ocean Dive". jedennews.com. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ "Voyage to the Bottom of the Earth". forbes.com. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ "To the Bottom of the Sea: Interview with Vanessa O'Brien". Explorersweb. Retrieved 2020-06-25.

- ^ @VictorVescovo (June 15, 2020). "Yesterday we just completed the deepest, longest dive ever. Mission specialist John Rost and I explored the Eastern…" ( Tweet). Retrieved 21 June 2020 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Mariana Trench: Don Walsh's son repeats historic ocean dive". bbc.com. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ "From father to son; the next generation of ocean exploration.Kelly Walsh repeats father'shistoric dive, 60 years later, on Father's Day weekend" (PDF). caladanoceanic.com. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ^ "On our latest dive, @WHOI research scientist Dr. Ying-Tsong "Y.-T". Lin joined @VictorVescovo to become, not only the first person born in Taiwan to go to the bottom of the Mariana Trench, but also the first from the Asian continent to do so.work=@CaladanOceanic twitter.com". Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ "WHOI Researcher Dives to Challenger Deep". whoi.edu. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ^ "First Taiwanese Native Dives to Challenger Deep" (PDF). caladanoceanic.com. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ^ "Caladan Oceanic Revisits Challenger Deep in Month-Long Dive Series". tritonsubs.com. Retrieved 29 July 2020.