| Part of a series on |

| Calligraphy |

|---|

|

| Part of a

series on Islam in China |

|---|

|

|

|

Sini (from Arabic: ٱلْخَطُ ٱلصِّينِيُّ, Al-khaṭ as-ṣīnī, lit. 'The Chinese script') is a calligraphic style used in China for the Arabic script. While Sini Script can refer to any type of Arabic Calligraphy influenced by Chinese Calligraphy, it exists on a spectrum in which the amount of Chinese influence increases as it is found further East. [1] [2] While Sini script resembles thuluth script, it adapts itself to local styles in Chinese Mosques. [3] [4] Although Sini script exists on a broad spectrum, the most well-known form of Sini script, standardized during the Ming Dynasty, is characterized by its “round, flowing” Arabic letters featuring the “tapered” style more commonly found in Chinese calligraphy. [5] It is also characterized by its thick horizontal and fine vertical strokes, a result that is achieved by using a brush rather than a qalam, which is the traditional writing pen for Islamic calligraphy. [4]

One Sini calligrapher is Hajji Noor Deen Mi Guangjiang (b. 1963). [6] [1]

Script Styles

Mosque Inscriptions

In Chinese mosques, Sini calligraphy is found on a variety of different surfaces including walls, boards and tablets made from stone or wood, and pillars made of concrete or stone, particularly near the mihrab or prayer niche. [1] The wooden boards containing Sini calligraphy found at the entrance of the prayer hall often contain a “ tasmiya” or invocation. [5] Sini calligraphy may be inscribed both horizontally or vertically depending on the surface. [1]

The vertical form of Sini Calligraphy, often found hanging on both sides of a doorway or on pillars, is influenced by the vertical style of Chinese calligraphy, particularly found in yinglian or duilian, the calligraphic artform of rhyming couplets. [1] A particularly distinct form of vertical Sini calligraphy can be achieved by following the Chinese tradition which contains the calligraphy within a box or square form and tilting it on its axis to form diamond-shaped calligraphy. [4] Examples of diamond-shaped Sini calligraphy can be found at the Great Mosque of Xi’an on columns flanking the prayer hall.

Objects

Sini script is also found on various objects produced for both local use and to be exported to the Muslim world. The David Collection in Copenhagen includes examples of bronze objects including a double-handed vessel with Chinese imagery dating to the seventeenth century and a bronze incense burner made during the reign of Ming emperor Zhengde, both inscribed with Sini calligraphy. [7] [8]

Manuscripts

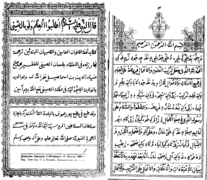

Among Islamic manuscripts in China, Sini script can be found in many Qur’ans produced in China throughout the Ming and Qing dynasties. Examples include a Qur’an from China dated to 1013/1605 in the Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art (QUR992) and a Qur’an from China dated to the 16th-18th century in the Tareq Rajab Museum (TSR-MS-11). [9] In these standardized 30-volume Qur’ans, most pages contain five to seven lines of script while the opening pages generally contain three lines. The script itself is generally large and wide-spaced. Although these Qur’ans may contain a variety of different scripts, the most frequently used script is derived from muhaqqaq. [9]

Specific calligraphic features separating Chinese Qur’anic script from its prototype may be noted. Certain letters from the Arabic alphabet are extended. For example, the tails of letters ra, za, waw as well as the terminals nun and sad rendered below the baseline extend further horizontally. Additionally, the initial of ba, particularly on the bismillah, tends to extend vertically yet in a curved manner. The terminal mim is rendered unconventionally, with either its tail hanging vertically rather than in parallel structure with the “sublinear” tails of other letters, or having a “curvilinear” form. In general, Chinese Qur’anic script contains more curlicues and sharper letter angles.

More decorative Sini calligraphy can be seen on the roundels exhibited on the double pages which precede each juz or section of the Qur’an. Depending on the Qur’an, the calligraphy may be more “Sinified” than others, containing more Chinese stylistic elements which may reduce its legibility to those unfamiliar to it. [9]

Historical Background

Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368)

Many Muslims migrated to China during the Mongol Chinggisid conquests which began the Yuan Era. During this era, the majority of the Muslim migrants consisted of soldiers employed by the Mongol rulers or craftspeople who were forced to relocate to China. [9] Further into the Yuan Era, in an attempt to prevent Chinese subjects from holding positions of power, Mongol rulers appointed intermediary government officials called semu guan many of whom were Muslims from West and Central Asia (52). [10] This began a “golden period” in China for Muslims, who began to acquire great prestige and wealth. [9]

As a result, the semu guan became overseers of the commercial exchange of goods between Central and West Asia and China. [10] Some of the goods transferred during this era consisted of Qur’anic manuscripts from the late thirteenth century and fourteenth century which heavily followed the Ilkhanid tradition. These manuscripts became prototypes for Chinese Qur’anic manuscripts. Additionally, with their newfound wealth, Muslim officials became patrons of not only Chinese Qur’ans but of mosques upon which forms of Arabic calligraphy were inscribed. [9] As wealthy Muslims began to educate themselves in Chinese literature and calligraphy, they became pioneers of a new hybridized form of Islamic and Chinese art. [10]

Ming Dynasty (1368 to 1644) and Qing Dynasty (1644-1911)

During the Ming Dynasty, the number of Muslims migrating to China decreased. As a result, contact with Central and West Asia was reduced resulting in a restriction of new Safavid and Ottoman art styles. Simultaneously, Han authorities began the process of Sinicization through intermarriage and language policies. This process was intensified during the Qing Dynasty. Despite this attempt of assimilation and acculturation, Muslim communities were able to retain the traditional Islamic art styles, drawing off of Ilkhanid archetypes particularly of Qur’ans, while creating a new hybridized derivation of Arabic and Chinese calligraphy. [9]

Many mosques were destroyed during the Qing Dynasty resulting in the destruction of many sources of Sini Calligraphy. [3]

Legacy

In the 20th Century, as more Chinese-Muslim students began to study overseas, some began to view Sini Calligraphy as less “authentic” than its Arabic predecessors. [11] Despite this, certain twentieth and twenty-first century artists such as Hajji Noor Deen Mi Quangjiang have tried to perpetuate this art form. [6]

The Sini calligraphic tradition has continued among Xi’an Muslim Hui communities who have incorporated Sini into their daily lives. Some embrace the performative nature of Sini calligraphy by taking classes while others display Sini in local settings such as restaurants, local shops and stores, as well as in their own houses. [6] To some, Sini calligraphy is seen as a means of performing and accommodating multiple identities of the Xi’an Hui Muslims. [6]

Gallery

-

The names of Allah in Chinese Arabic Sini Script

-

Quran with Chinese translation recorded in both Arabic script of Xiao'erjing and Chinese scripts

-

Qur'anic Manuscript in Sini script

-

A book on law in Arabic, with a parallel Chinese translation in the Xiao'erjing Arabic script, published in Tashkent in 1899

-

Calligraphy on a plaque in the Great Mosque of Xi'an in Sini script

-

The Basmala in Sini script

-

Taḥmīd ("Praise be to God") in Arabic Ṣīnī-style calligraphy at the Great Mosque of Xi'an

See also

- Islamic calligraphy

- Chinese calligraphy

- Xiao'erjing: the use of Arabic script for writing Chinese language

External links

- Islamic Calligraphy in China, China Heritage Newsletter, Number 5 (March 2006)

- Hajji Noor Deen's Website, features Sini galleries

- Islamic Chinese Art ( Dru C. Gladney's photo album on Flickr.com)

- ^ a b c d e Stöcker-Parnian, Barbara (2013). Gharipour, Mohammad (ed.). Chapter Eight Calligraphy in Chinese Mosques: At the Intersection of Arabic and Chinese Calligraphy in "Calligraphy and Architecture in the Muslim World". Edinburgh University Press. p. 145.

- ^ Smith, G. Rex (1994). Roper, Geoffrey (ed.). "World survey of Islamic manuscripts". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 6 (2): 73.

- ^ a b Armijo, Jacequeline (2008). "Islam in China". Asian Islam in the 21st Century. Oxford University Press. p. 203.

- ^ a b c Ghoname, Hala (2015). Sini Calligraphy: The Preservation of Chinese Muslims' Cultural Heritage. LAP Lambert Academic Publishing. p. 31. ISBN 9783659776519.

- ^

a

b Garnuet, Anthony (March 2006).

"Islamic Calligraphy in China". China Heritage Newsletter. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

{{ cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status ( link) - ^ a b c d Wang, Jing (2019). Chapter 4: Writing in Palimpsests: Performative Acts and Tactics in Everyday Life of Chinese Muslims in "Emergent Religious Pluralisms". Palgrave Macmillan, Springer Nature Switzerland AG. pp. 91–92. ISBN 9783030138110.

- ^ "Gold-flecked bronze vessel". The David Collection. 2022. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- ^ "Incense burner, cast bronze". The David Collection. 2022. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fraser, Marcus. "Beyond the Taklamakan: The Origins and Stylistic Development of Qurʾan Manuscripts in China". Fruit of Knowledge, Wheel of Learning (Vol II): Essays in Honour of Professor Robert Hillenbrand. 2: 181–185 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c Lipman, Jonathan N. (January 1998). Familiar Strangers: A History of Muslims in Northwest China (1st ed.). University of Washington Press. p. 53. ISBN 9780295976440.

- ^ Chorbachi, Wasma'a K. (1999). Arabic Calligraphy in Twentieth-Century China, paper presented at a conference, ‘‘The Legacy of Islam in China: An International Symposium in Memory of Joseph F. Fletcher". Harvard University.