| Mimiviridae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Tupanvirus | |

|

Virus classification

| |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Varidnaviria |

| Kingdom: | Bamfordvirae |

| Phylum: | Nucleocytoviricota |

| Class: | Megaviricetes |

| Order: | Imitervirales |

| Family: | Mimiviridae |

| Subfamilies and genera | |

| |

Mimiviridae is a family of viruses. Amoeba and other protists serve as natural hosts. The family is divided in up to 4 subfamilies. [1] [2] [3] [4] Viruses in this family belong to the nucleocytoplasmic large DNA virus clade (NCLDV), also referred to as giant viruses.

Mimiviridae is the sole recognized member of order Imitervirales. Phycodnaviridae and Pandoraviridae of Algavirales are sister groups of Mimiviridae in many phylogenetic analyses. [5]

History

The first member of this family, Mimivirus, was discovered in 2003, [6] and the first complete genome sequence was published in 2004. [7] However, the mimivirus Cafeteria roenbergensis virus [8] was isolated and partially characterized in 1995, [9] although the host was misidentified at the time, and the virus was designated BV-PW1. [8]

Taxonomy

Group: dsDNA

- Family: Mimiviridae

Family Mimiviridae is currently divided into three subfamilies. [2] [3] [10]

- One subfamily (genus

Mimivirus, proposed names: Megavirinae or Megamimivirinae) is divided into three "lineages":

- A — Mimivirus group: includes Acanthamoeba polyphaga Mimivirus, Hirudovirus, Mamavirus, Kroon virus, Lentille virus, Terra2, Niemeyer virus, Samba virus. [11] [12]

- B — Moumouvirus group: includes Moumouvirus, Saudi moumouvirus, Moumouvirus goulette, Monve virus (aka Moumouvirus monve), and Ochan virus. [13] [11] [14] [12]

- C — Courdo11 virus group: includes Mont1, [11] Courdo7, Courdo11, Megavirus chilensis, LBA111, Powai lake megavirus and Terra1. [15] [16]

- The majority of Mimiviridae appear to belong to this subfamily (Mimiviruses). [10]

- It is sometimes also referred to as Mimiviridae group I. [17]

- The second subfamily ( Cafeteriavirus or Mimiviridae group II) includes the Cafeteria roenbergensis virus (CroV). [8]

- The Klosneuvirinae have been proposed as a third subfamily and are divided into four "lineages": Klosneuvirus, Indivirus, Catovirus and Hokovirus. [3] They seem to be closely related to the Mimivirus subfamily rather than the Cafeteriavirus subfamily (and so might be summarized in Mimivirus group I as well). [3] The first isolate from this group is Bodo saltans virus infecting the kinetoplastid Bodo saltans. [18]

- Tupanvirus strains have been discussed to comprise a sister group of mimiviruses. [4]

Furthermore, it has been proposed either to extend Mimiviridae by an additional tentative group III (subfamily Mesomimivirinae) or to classify this group as a sister family Mesomimiviridae instead, [19] comprising legacy OLPG (Organic Lake Phycodna Group). This extension (or sister family) may consist of the following:

- Phaeocystis globosa virus (PgV, represented by PgV-16T strain) and Phaeocystis pouchetii virus (PpV, e. g. PpV 01)

- "Organic Lake Phycodnavirus" 1 and 2 (OLV1, OLV2, hosts of Organic Lake virophage)

- "Yellowstone Lake Mimivirus" [12] [20] aka "Yellowstone Lake Phycodnavirus" 4 ( YSLGV4)

- Chrysochromulina ericina virus (CeV, e. g. CeV 01)

- Aureococcus anophagefferens virus ( [21] AaV)

- Pyramimonas orientalis virus (PoV)

- Tetraselmis virus (TetV-1) [22]

This group seems to be closely related to Mimiviridae rather than to Phycodnaviridae and therefore is sometimes referred to as a further subfamily candidate Mesomimivirinae. Sometimes the extended family Mimiviridae is referred to as Megaviridae although this has not been recognized by ICTV; alternatively the extended group may be referred to just as Mimiviridae. [3] [23] [24] [25] [26] [17]

With recognition of new order Imitervirales by the ICTV in March 2020 there is no longer need to extend the Mimiviridae family to comprise a group of viruses of the observed high diversity. Instead, the extension (or at least its main clade) may be referred to as a sister family Mesomimiviridae. [19]

Although only a couple of members of this order have been described in detail it seems likely there are many more awaiting description and assignment [27] [28] Unassigned members include Aureococcus anophagefferens virus (AaV), CpV-BQ2 and Terra2.[ citation needed]

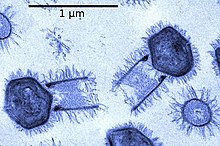

Structure

[18] Viruses in Mimiviridae have icosahedral and round geometries, with between T=972 and T=1141, or T=1200 symmetry. The diameter is around 400 nm, with a length of 125 nm. Genomes are linear and non-segmented, around 1200kb in length. The genome has 911 open reading frames. [1]

| Genus | Structure | Symmetry | Genomic arrangement | Genomic segmentation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mimivirus | Icosahedral | T=972-1141 or T=1200 (H=19 +/- 1, K=19 +/- 1) | Linear | Monopartite |

| Klosneuvirus | Icosahedral | |||

| Cafeteriavirus | Icosahedral | T=499 | Linear | Monopartite |

| Tupanvirus | Tailed |

Life cycle

Replication follows the DNA strand displacement model. DNA-templated transcription is the method of transcription. Amoeba serve as the natural host. [1]

| Genus | Host details | Tissue tropism | Entry details | Release details | Replication site | Assembly site | Transmission |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mimivirus | Amoeba | None | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Passive diffusion |

| Klosneuvirus | microzooplankton | None | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Cytoplasm | Passive diffusion |

| Cafeteriavirus | microzooplankton | None | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Cytoplasm | Passive diffusion |

Molecular biology

Three putative DNA base excision repair enzymes were characterized from Mimivirus. [29] The base excision repair (BER) pathway was experimentally reconstituted using the purified recombinant proteins uracil-DNA glycosylase (mvUDG), AP endonuclease (mvAPE), and DNA polymerase X protein (mvPolX). [29] When reconstituted in vitro mvUDG, mvAPE and mvPolX function cohesively to repair uracil-containing DNA predominantly by long patch base excision repair, and thus these processes likely participate in the BER pathway early in the Mimivirus life cycle. [29]

Clinical

Mimiviruses have been associated with pneumonia but their significance is currently unknown. [30] The only virus of this family isolated from a human to date is LBA 111. [31] At the Pasteur Institute of Iran (Tehran), researchers identified mimivirus DNA in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and sputum samples of a child patient, utilizing real-time PCR (2018). Analysis reported 99% homology of LBA111, lineage C of the Megavirus chilensis. [32] With only a few reported cases previous to this finding, the legitimacy of the mimivirus as an emerging infectious disease in humans remains controversial. [33] [34]

Mimivirus has also been implicated in rheumatoid arthritis. [35]

See also

References

- ^ a b c "Viral Zone". ExPASy. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ a b ICTV. "Virus Taxonomy: 2014 Release". Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Schulz, Frederik; Yutin, Natalya; Ivanova, Natalia N.; Ortega, Davi R.; Lee, Tae Kwon; Vierheilig, Julia; Daims, Holger; Horn, Matthias; Wagner, Michael (7 April 2017). "Giant viruses with an expanded complement of translation system components" (PDF). Science. 356 (6333): 82–85. Bibcode: 2017Sci...356...82S. doi: 10.1126/science.aal4657. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 28386012. S2CID 206655792., UCPMS ID: 1889607, PDF

- ^ a b Abrahão, Jônatas; Silva, Lorena; Silva, Ludmila Santos; Khalil, Jacques Yaacoub Bou; Rodrigues, Rodrigo; Arantes, Thalita; Assis, Felipe; Boratto, Paulo; Andrade, Miguel; Kroon, Erna Geessien; Ribeiro, Bergmann; Bergier, Ivan; Seligmann, Herve; Ghigo, Eric; Colson, Philippe; Levasseur, Anthony; Kroemer, Guido; Raoult, Didier; Scola, Bernard La (27 February 2018). "Tailed giant Tupanvirus possesses the most complete translational apparatus of the known virosphere". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 749. Bibcode: 2018NatCo...9..749A. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03168-1. PMC 5829246. PMID 29487281. Fig. 4 and §Discussion: "Considering that tupanviruses comprise a sister group to amoebal mimiviruses…"

- ^ Bäckström D, Yutin N, Jørgensen SL, Dharamshi J, Homa F, Zaremba-Niedwiedzka K, Spang A, Wolf YI, Koonin EV, Ettema TJ (2019). "Virus genomes from deep sea sediments expand the ocean megavirome and support independent origins of viral gigantism". mBio. 10 (2): e02497-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02497-18. PMC 6401483. PMID 30837339. PDF

- ^ Suzan-Monti, M; La Scola, B; Raoult, D (2006). "Genomic and evolutionary aspects of Mimivirus". Virus Res. 117 (1): 145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2005.07.011. PMID 16181700.

- ^ Raoult, D.; Audic, S; Robert, C; Abergel, C; Renesto, P; Ogata, H; La Scola, B; Suzan, M; Claverie, JM (2004). "The 1.2-Megabase Genome Sequence of Mimivirus". Science. 306 (5700): 1344–50. Bibcode: 2004Sci...306.1344R. doi: 10.1126/science.1101485. PMID 15486256. S2CID 84298461.

- ^ a b c Matthias G. Fischer; Michael J. Allen; William H. Wilson; Curtis A. Suttle (2010). "Giant virus with a remarkable complement of genes infects marine zooplankton". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (45): 19508–13. Bibcode: 2010PNAS..10719508F. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007615107. PMC 2984142. PMID 20974979.

- ^ D.R. Garza; C.A. Suttle (1995). "Large double-stranded DNA viruses which cause the lysis of a marine heterotrophic nanoflagellate (Bodo sp.) occur in natural marine viral communities". Aquatic Microbial Ecology. 9 (3): 203–210. doi: 10.3354/ame009203.

- ^ a b Colson P, Fournous G, Diene SM, Raoult D (2013). "Codon usage, amino acid usage, transfer RNA and amino-acyl-tRNA synthetases in Mimiviruses". Intervirology. 56 (6): 364–75. doi: 10.1159/000354557. PMID 24157883.

- ^ a b c Gaia M, Benamar S, Boughalmi M, Pagnier I, Croce O, Colson P, Raoult D, La Scola B (2014). "Zamilon, a novel virophage with Mimiviridae host specificity". PLOS ONE. 9 (4): e94923. Bibcode: 2014PLoSO...994923G. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094923. PMC 3991649. PMID 24747414.

- ^ a b c See also Abrahão & et al. 2018, fig. 4 on p. 5

- ^ Desnues C, La Scola B, Yutin N, Fournous G, Robert C, Azza S, Jardot P, Monteil S, Campocasso A, Koonin EV, Raoult D (October 2012). "Provirophages and transpovirons as the diverse mobilome of giant viruses". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 (44): 18078–83. Bibcode: 2012PNAS..10918078D. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208835109. PMC 3497776. PMID 23071316.

- ^ Yutin N, Wolf YI, Koonin EV (October 2014). "Origin of giant viruses from smaller DNA viruses not from a fourth domain of cellular life". Virology. 466–467: 38–52. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.06.032. PMC 4325995. PMID 25042053.

- ^ Gaia M, Pagnier I, Campocasso A, Fournous G, Raoult D, La Scola B (2013). "Broad spectrum of mimiviridae virophage allows its isolation using a mimivirus reporter". PLOS ONE. 8 (4): e61912. Bibcode: 2013PLoSO...861912G. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061912. PMC 3626643. PMID 23596530.

- ^ For LBA111 and Powai lake megavirus see also Abrahão & et al. 2018, fig. 4 on p. 5

- ^ a b Zhang W, Zhou J, Liu T, Yu Y, Pan Y, Yan S, Wang Y (October 2015). "Four novel algal virus genomes discovered from Yellowstone Lake metagenomes". Sci Rep. 5: 15131. Bibcode: 2015NatSR...515131Z. doi: 10.1038/srep15131. PMC 4602308. PMID 26459929.

- ^ a b Deeg, C.M.; Chow, E.C.T.; Suttle, C.A. (2018). "The kinetoplastid-infecting Bodo saltans virus (BsV), a window into the most abundant giant viruses in the sea". eLife. 7: e33014. doi: 10.7554/eLife.33014. PMC 5871332. PMID 29582753.

- ^ a b Jonathan Filée: Giant viruses and their mobile genetic elements: the molecular symbiosis hypothesis, in: Current Opinion in Virology, Volue 33, December 2018, pp. 81–88; bioRxiv 2018/04/11/299784

- ^ NCBI Complete genomes: Viruses, look for 'Yellowstone Lake'

- ^ Moniruzzaman, Mohammad; LeCleir, Gary R.; Brown, Christopher M.; Gobler, Christopher J.; Bidle, Kay D.; Wilson, William H.; Wilhelm, Steven W. (2014). "Genome of brown tide virus (AaV), the little giant of the Megaviridae, elucidates NCLDV genome expansion and host–virus coevolution". Virology. 466–467: 60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.06.031. PMID 25035289.

-

^ Schvarcz CR, Steward GF (May 2018).

"A giant virus infecting green algae encodes key fermentation genes". Virology. 518: 423–433.

doi:

10.1016/j.virol.2018.03.010.

PMID

29649682.

- "A new giant virus found in the waters of Oahu, Hawaii". ScienceDaily (Press release). 3 May 2018.

- ^ Koonin EV, Krupovic M, Yutin N (April 2015). "Evolution of double-stranded DNA viruses of eukaryotes: from bacteriophages to transposons to giant viruses". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1341 (1): 10–24, see Figure 3. Bibcode: 2015NYASA1341...10K. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12728. PMC 4405056. PMID 25727355.

- ^ Yutin N, Colson P, Raoult D, Koonin EV (April 2013). "Mimiviridae: clusters of orthologous genes, reconstruction of gene repertoire evolution and proposed expansion of the giant virus family". Virol. J. 10: 106. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-106. PMC 3620924. PMID 23557328.

- ^ Blog of Carolina Reyes, Kenneth Stedman: Are Phaeocystis globosa viruses (OLPG) and Organic Lake phycodnavirus a part of the Phycodnaviridae or Mimiviridae?, on ResearchGate, Jan. 8, 2016

- ^ Maruyama F, Ueki S (2016). "Evolution and Phylogeny of Large DNA Viruses, Mimiviridae and Phycodnaviridae Including Newly Characterized Heterosigma akashiwo Virus". Front Microbiol. 7: 1942. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01942. PMC 5127864. PMID 27965659.

- ^ Ghedin E, Claverie JM (August 2005). "Mimivirus relatives in the Sargasso sea". Virol. J. 2: 62. arXiv: q-bio/0504014. Bibcode: 2005q.bio.....4014G. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-2-62. PMC 1215527. PMID 16105173.

- ^ Monier A, Claverie JM, Ogata H (2008). "Taxonomic distribution of large DNA viruses in the sea". Genome Biol. 9 (7): R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-7-r106. PMC 2530865. PMID 18598358.

- ^ a b c Lad SB, Upadhyay M, Thorat P, Nair D, Moseley GW, Srivastava S, Pradeepkumar PI, Kondabagil K. Biochemical Reconstitution of the Mimiviral Base Excision Repair Pathway. J Mol Biol. 2023 Sep 1;435(17):168188. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2023.168188. Epub 2023 Jun 26. PMID: 37380013

- ^ Saadi H, Pagnier I, Colson P, Cherif JK, Beji M, Boughalmi M, Azza S, Armstrong N, Robert C, Fournous G, La Scola B, Raoult D (August 2013). "First isolation of Mimivirus in a patient with pneumonia". Clin. Infect. Dis. 57 (4): e127–34. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit354. PMID 23709652.

- ^ Yoosuf N, Pagnier I, Fournous G, Robert C, La Scola B, Raoult D, Colson P (April 2014). "Complete genome sequence of Courdo11 virus, a member of the family Mimiviridae". Virus Genes. 48 (2): 218–23. doi: 10.1007/s11262-013-1016-x. PMID 24293219. S2CID 12038772.

- ^ Sakhaee, Fatemeh; Vaziri, Farzam; Bahramali, Golnaz; Davar Siadat, Seyed; Fateh, Abolfazl (October 2020). "Pulmonary Infection Related to Mimivirus in Patient with Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 26 (10): 2524–2526. doi: 10.3201/eid2610.191613. PMC 7510730. PMID 32946733.

- ^ La Scola, Bernard; Marrie, Thomas J.; Auffray, Jean-Pierre; Raoult, Didier (March 2005). "Mimivirus in pneumonia patients". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (3): 449–452. doi: 10.3201/eid1103.040538. PMC 3298252. PMID 15757563.

- ^ Saadi, Hanene; Pagnier, Isabelle; Colson, Philippe; Kanoun Cherif, Jouda; Beji, Majed; Boughalmi, Mondher; Azza, Saïd; Armstrong, Nicholas; Robert, Catherine; Fournous, Ghislain; La Scola, Bernard (24 May 2013). "First isolation of Mimivirus in a patient with pneumonia". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 57 (4): e127–e134. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit354. PMID 23709652 – via Oxford Academic.

- ^ Shah, N.; Hulsmeier, A. J.; Hochhold, N.; Neidhart, M.; Gay, S.; Hennet, T. (2013). "Exposure to Mimivirus Collagen Promotes Arthritis". Journal of Virology. 88 (2): 838–45. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03141-13. PMC 3911627. PMID 24173233.