This article relies largely or entirely on a

single source. (February 2024) |

| Part of the Politics series |

| Electoral systems |

|---|

|

|

|

Descending Solid Coalitions (DSC) is a ranked-choice voting system. It is designed to preserve the advantages of instant-runoff voting, while satisfying monotonicity. [1] It was developed by voting theorist Douglas Woodall as an improvement on (and replacement for) the use of the alternative vote.

A minor variant, Descending Acquiescing Coalitions (DAC), counts ballots slightly differently. [1]

Procedure

A solid coalition consists of all voters who prefer every member of a set of candidates to every non-member.

DSC assigns every coalition (i.e. set) of candidates a score equal to their total number of supporters. Coalitions are ranked by their number of supporters (in descending order).

At each counting step, all candidates who are not supported by the coalition are eliminated, unless doing so would eliminate all candidates. When only one candidate remains, that candidate is elected. [1]

DAC differs in defining a supporter as a voter who ranks every member of the coalition higher than or equal to every non-member. When neither equal-ranked nor truncated ballots are permitted, the methods are identical. [1] If truncated ballots are allowed, unranked candidates are treated as equally ranked below every ranked candidate.

Properties

DAC satisfies majority, monotonicity, participation, plurality, later-no-help, and independence of clones. [1] DSC satisfies the above properties apart from later-no-help, replacing it with later-no-harm.

It fails the Condorcet criterion, independence of irrelevant alternatives, independence of Smith-dominated alternatives, and the honest favorite criterion.

Comparison to instant-runoff

DAC was intended to serve as a practical alternative to instant-runoff voting, preserving most of the positive attributes of IRV while mitigating many of its downsides. (In this respect, it is similar to approval voting, which is often argued to be a "strict improvement" with few or no downsides compared to plurality.)

DAC maintains the most commonly-cited advantages of IRV, namely independence of clones, later-no-harm, and the mutual majority criterion. [1] However, DAC also satisfies both monotonicity and participation, meaning a candidate cannot lose an election just because they have "too many supporters." [1]

Example

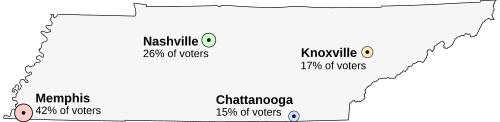

Suppose that Tennessee is holding an election on the location of its capital. The population is concentrated around four major cities. All voters want the capital to be as close to them as possible. The options are:

- Memphis, the largest city, but far from the others (42% of voters)

- Nashville, near the center of the state (26% of voters)

- Chattanooga, somewhat east (15% of voters)

- Knoxville, far to the northeast (17% of voters)

The preferences of each region's voters are:

| 42% of voters Far-West |

26% of voters Center |

15% of voters Center-East |

17% of voters Far-East |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

The possible coalitions have the following strengths:

- 58 {N, C, K}

- 42 {M}

- 42 {M, N}

- 42 {M, N, C}

- 32 {C, K}

- 26 {N, C}

- 26 {N}

- 17 {K}

- 15 {C}

Counting steps:

- {N, C, K} has the largest coalition, so Memphis is eliminated (as it is not included).

- The next-strongest set is {M}, which would eliminate all candidates, so it is ignored.

- The next-strongest set is {M, N}, which would eliminate candidates {C, K}.

All candidates other than Nashville have been eliminated, leaving N the winner.

DSC tends to select more moderate alternatives than IRV (Nashville, instead of Knoxville) because it considers all the coalitions that might support a candidate, instead of only considering the highest-ranked candidate who has not been eliminated.

Notice that while half of the votes held Memphis to be the worst alternative, Memphis supporters' votes remained useful in securing their second choice, Nashville. If the Memphis voters had not listed any preferences after Memphis, Chattanooga would be the winner.