| Babini Group (Raggruppamento Babini/Brigata Corazzata Speciale) | |

|---|---|

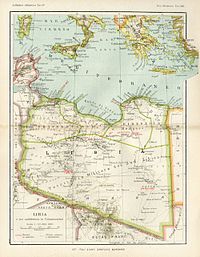

M13/40 tanks on the streets of

Tripoli, March 1941 | |

| Active | 1940–1941 |

| Country | Italy |

| Branch | Army |

| Type | Armoured brigade |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | General Valentino Babini |

The Babini Group ( Italian: Raggruppamento Babini, also known as the Special Armoured Brigade Brigata Corazzata Speciale) was an ad hoc armoured unit. The group was formed by the Italian Royal Army (Regio Esercito Italia) in Italian North Africa (Libya) at the start of the Western Desert Campaign of the Second World War. The group was formed in Libya, to be part of an armoured division assembled from tanks in the colony and from units sent from Italy. The new division was incomplete when the British began Operation Compass in December but the Babini Group fought in defence of the area between Mechili and Derna in late January.

On 23 January, the group managed to inflict tank losses during a counter-attack on the 11th Hussars and force a delay in the Australian advance on Derna. The group then formed a rearguard for the 10th Army as it retreated from Derna and Mechili round the Jebel Akhdar towards the port of Benghazi. The Babini Group was destroyed south of the port at the Battle of Beda Fomm (6–7 February), when the Litoranea Balbo (Via Balbia) was cut by Combeforce. The Italians failed to concentrate their remaining tanks at the head of the column before Combeforce was reinforced and were defeated in detail, with possibly only nine tanks escaping to the south.

Background

32nd Tank Infantry Regiment

The 32nd Tank Infantry Regiment was formed on 1 December 1938 and on 1 February 1939 became part of the 132nd Armored Division "Ariete", the second armoured division of the Royal Italian Army ( Regio Esercito). After the Italian declaration of war on 11 June 1940, the 32nd Tank Infantry Regiment moved with the Ariete Division from Veneto to the border with France, as part of the Army of the Po (Armata del Po), ready to exploit a breakthrough but the war ended so quickly that the division did not participate. [1] On 28 July 1939, the I and II Tank Battalion "M"s received 96 Fiat M11/39 tanks to replace their Fiat 3000s. The inadequacies of the M11/39 tanks led to a decision on 26 October 1939, to replace them with M13/40 tanks and the first batch, built by Ansaldo at Genoa in October 1940, were used to equip the III Tank Battalion "M" with 37 new M13/40s. [2]

Libyan Tank Command

In 1940, the Italian army had three armoured divisions in Europe, which were needed for the occupation of Albania and the invasion of Greece. The I Tank Battalion "M" (Major Victor Ceva) and the II Tank Battalion "M" (Major Eugenio Campanile) landed their M11/39 tanks in Libya on 8 July 1940 and transferred from the 32nd Tank Infantry Regiment to the command of the 4th Tank Infantry Regiment. The two battalions had an establishment of 600 men, 72 tanks, 56 vehicles, 37 motorcycles and 76 trailers. The medium tanks reinforced the three hundred and twenty-four L3/35 tankettes already in Libya. [2]

On 29 August 1940 the commander of the Northern Africa High Command Marshal Rodolfo Graziani ordered, on advice of General Valentino Babini, that the Libyan Tank Command ( Italian: Comando Carri Armati Della Libia), entrusted to General Valentino Babini, be constituted under his direct control. All tanks in Italian Libya were to come under the new arrangements laid down in Graziani's order N. 1/210045.

- Libyan Tank Command, General Valentino Babini

[3]

[4]

[5]

- 1st Tank Group (

Italian: 1° Raggruppamento Carristi), Colonel Pietro Aresca (4th Tank Infantry Regiment), destined to operate with the

XXIII Corps

- Command of the 4th Tank Infantry Regiment

- I Tank Battalion "M" ( M11/39 tanks)

- XXI Tank Battalion "L" ( L3/35 tankettes)

- LXII Tank Battalion "L" (L3/35 tankettes)

- LXIII Tank Battalion "L" (L3/35 tankettes)

- 2nd Tank Group (

Italian: 2° Raggruppamento Carristi), Colonel Antonio Trivioli, destined to operate with the Libyan Divisions Group

- II Tank Battalion "M" (minus one company; M11/39 tanks)

- IX Tank Battalion "L" (L3/35 tankettes)

- XX Tank Battalion "L" (L3/35 tankettes)

- LXI Tank Battalion "L" (L3/35 tankettes)

- Mixed Tank Battalion, destined to operate with the

Maletti Group

- 1x Medium company (from the II Tank Battalion "M")

- 1x Light company (from the LX Tank Battalion "L")

- LX Tank Battalion "L" (minus one company; L3/35 tankettes), destined to operate with the XXI Corps

- 1st Tank Group (

Italian: 1° Raggruppamento Carristi), Colonel Pietro Aresca (4th Tank Infantry Regiment), destined to operate with the

XXIII Corps

When Operation Compass began on 9 December 1940, the IX Tank Battalion "L" was still with the 2nd Libyan Division, the II Tank Battalion "M" was with the Maletti Group and the LXIII and XX Tank Battalion "L"s were in reserve with the XXI Corps HQ east of the Frontier Wire in Egypt. [6]

The III Tank Battalion "M" (Lieutenant-Colonel Carlo Ghioldi) from the 32nd Tank Infantry Regiment, equipped with thirty-seven M13/40 tanks in two companies, arrived in Benghazi in late September and joined the 417 vehicles of various types in the Libyan Tank Command to begin training. In November, the III Tank Battalion "M" was sent to Mechili and on 9 December, Operation Compass began to push back the 10th Army from Sidi Barrani, 62 mi (100 km) inside Egypt. The III Tank Battalion "M" was sent forward to Sollum and the Halfaya Pass. [2] On 22 January, the VI Tank Battalion "M" arrived at Benghazi, with thirty-seven M13/40s and another thirty-six M13/40s for the XXI Tank Battalion "L", which was waiting at Benghazi to convert to the new vehicle, having lost its L3/35 tankettes in the fall of Tobruk. Neither battalion had time to acclimatise or train but were sent to reinforce the Bignami Group (Raggruppamento Bignani Colonel Riccardo Bignami) near Solluch. [2]

Prelude

Maletti Group

The Maletti Group (Raggruppamento Maletti General Pietro Maletti) was formed at Derna the same day as the main motorised unit of the 10th Army and the first Italian combined arms unit in North Africa. The group comprised the LX Tank Battalion "L", the remaining M11/39 company from the II Tank Battalion "M", seven Libyan motorised infantry battalions, motorised artillery and supply units. [4] [5] After the invasion of Egypt in September 1940, the 10th Army began to prepare an advance to Mersa Matruh for 16 December but was forestalled by Operation Compass. Only the IX Tank Battalion "L", the II Tank Battalion "M" with M11/39s, with the Maletti Group at Nibeiwa camp and the LXIII and XX Tank Battalion "L"s were still in Egypt. [7] The camp at Nibeiwa was a rectangle about 1.6 km × 2.4 km (1 mi × 1.5 mi), with a bank and an anti-tank ditch. A minefield had been laid but at the north-west corner, there was a gap for delivery lorries and a British night reconnaissance found the entrance. [8]

The British attacked the rear of the camp from the north-west at 5:00 a.m. on 9 December, with infantry and Matilda infantry tanks leading and Bren carriers on the flanks, all firing on the move. About twenty of the Maletti Group M11/39s outside the camp, were destroyed in the first rush. By 10:40 a.m., the camp had been overrun and 2,000 Italian and Libyan prisoners captured, along with a large quantity of supplies and water, for a British loss of 56 men. [9] After the battle an Australian war correspondent, Alan Moorehead, visited Nibeiwa and saw tanks inside the camp facing in all directions and light tank wrecks at the west wall where the Maletti Group had made its last stand. [10] In his history of the 32nd Tank Infantry Regiment, Maurizio Parri wrote that a company of II Tank Battalion "M" M11/39s had tried to counter-attack the British Matildas but the crews misunderstood flag signals which caused delays and the attack failed. [2] Maletti was wounded while rallying his men, then retreated to his tent with a machine-gun where he was killed. [10]

Babini Group

In early November, the V Tank Battalion "M" (Lieutenant-Colonel Emilio Iezzi), arrived at Benghazi with thirty-seven M13/40s in two companies and on 25 November, Graziani ordered the establishment at Marsa Lucch of the Special Armoured Brigade/Babini Group (Brigata Corazzata Speciale/Raggruppamento Babini) to be commanded by General Valentino Babini, with the III Tank Battalion "M" (less detachment) and the V Tank Battalion "M", combined with the L3/35s of the 4th Tank Infantry Regiment. The medium tank crews were inexperienced and lacked training, many of the officers having only recently come from very short courses at training schools. The Tank Battalion "L"s remained with the infantry divisions in Egypt, despite this interrupting training with the new M13/40s, which was complicated by the M13s coming from the first production batch with many mechanical defects. Only three of the III Tank Battalion "M" tanks had radios, which made the other crews reliant on flag signals limited to halt, forward, backwards, right, left, slow down and speed up. [2]

The Babini Group had an infantry regiment comprising three " Bersaglieri" battalions, a motorcycle battalion, an artillery regiment, two anti-tank gun companies, an engineer company and supply units. [11] On 11 December the under-trained III Tank Battalion "M" and the LI Tank Battalion "L" in L3/35 tankettes, was made available to the 10th Army. Next day, two companies of the III Battalion were sent to Sollum, several tanks to Sidi Aziz and the rest to Halfaya, before the battalion was ordered to retreat west of Gazala to cover the rear of Tobruk. The 1st Tank Company (Lieutenant Elio Castanello) was detached to reinforce Bardia and the drive from Sidi Aziz exposed many technical failings in the M13/40s, including defective fuel pumps, inconsistent fuel consumption between tanks, engine wear and brittle armour. [a] In December, Comando Supremo (supreme command of the Italian armed forces) in Rome, reinforced the Babini Group with the V Tank Battalion "M" of the 132nd Armored Division "Ariete" to join the III Tank Battalion "M". [11] The V Tank Battalion "M" was sent Derna to join the Babini Group on 16 January 1941 but a lack of tank transporters meant that the M13/40 had to drive on their tracks, which caused many breakdowns and on 19 December, Comando Supremo arranged to rush every available M13/40 to Tripoli. [2]

Operations

Derna–Mechili

The area east of the Jebel Akhdar mountains around Derna, was garrisoned by XX Corps (Lieutenant-General Annibale Bergonzoli) with the 60th Infantry Division "Sabratha" and the Babini Group, which had already lost some of its tanks in Tobruk. The III Medium Battalion and the V Medium Battalion had an establishment of 55 M13/40 tanks each, which should have amounted to at least 120 M13s in the group but 82 had recently been landed at Benghazi. [12] The new tanks needed ten days to be made battle-worthy and a three-day journey to reach Mechili but in the crisis, tanks were rushed forward, driving on their tracks due to a lack of tank transporters, which reduced the serviceability of the vehicles. A defensive position was established by the 60th Infantry Division "Sabratha" on a line from Derna along Wadi Derna, with the Babini Group concentrating at El Ghezze Scebib, south of Mechili and Giovanni Berta and Chaulan, to guard the flank and rear of the infantry. [13]

On 22 January, the British advanced towards Derna with the 19th Australian Brigade and sent another Australian brigade to reinforce the 4th Armoured Brigade, 7th Armoured Division, south of the Jebel Akhdar, for an advance on Mechili. [13] Next day, the 10th Army commander, General Giuseppe Tellera ordered a counter-attack against the British as they approached Mechili, to avoid an envelopment of XX Corps from the south but communication within the Babini Group was slow, only the tanks of senior commanders having wireless sets. Next day, 10–15 M13/40s of the Babini Group attacked the 7th Hussars of the 4th Armoured Brigade, which was heading west to cut the Derna–Mechili track north of Mechili. The Italians fired on the move, hit several tanks and pursued as the British swiftly retired, calling for help from the 2nd Royal Tank Regiment (2nd RTR) as they did, which ignored the signals through complacency. By 11:00 a.m., the British had lost several light tanks and a cruiser tank, one cruiser had a jammed gun and the third was retiring at speed, after needing fifty rounds to knock out two M13s. Eventually the 2nd RTR was alerted, caught the Italian tanks while sky-lined on a ridge and knocked out seven tanks by 11:30 a.m., the British losing of the cruiser and six light tanks. [14] [15]

Tellera intended to use the Babini Group to harass the British southern flank to cover a withdrawal from Mechili but Graziani ordered him to wait on events. By the evening, a report had arrived from Babini that the group was down from 50 to 60 tanks and that their performance had been disappointing, along with alarmist tales of 150 British tanks advancing round the southern flank. Graziani ordered Tellera to disengage the Babini Group by next morning. Some tanks had been held back at Benghazi and work had begun on a defensive position at Sirte, 440 mi (710 km) to the south. [16] In the north, on 25 January, the 2/11th Australian Battalion engaged the 60th Infantry Division "Sabratha" and the 10th Bersaglieri Regiment of the Babini Group at Derna airfield, making slow progress against determined resistance. Italian bombers and fighters flew sorties against the 2/11th Australian Battalion, as it attacked the airfield and high ground at Siret el Chreiba. The 10th Bersaglieriswept the flat ground with field artillery and machine-guns, stopping the Australian advance 3,000 yd (1.7 mi; 2.7 km) short of the objective. [17]

On 26 January, Graziani ordered Tellera to continue the defence of Derna and to use the Babini Group to stop an advance westwards from Mechili–Derna. Tellera requested more tanks but this was refused, until the defences of Derna began to collapse the next day. During the day, the 2/4th Australian Battalion, in the Derna– Giovanni Berta area, attacked and cut the Derna–Mechili road, a company crossing Wadi Derna during the night. On the northern edge of the wadi, a bold counter-attack, with artillery support, was made across open ground by the 10th Bersaglieri of the Babini Group, which with reports in the morning that the group was attacking round the southern flank, deterred the Australians from continuing the advance on Derna; forty Bersaglieri were killed and 56 captured. [18] The 4th Armoured Brigade was ordered to encircle Mechili and cut the western and north-western exits, while the 7th Armoured Brigade cut the road from Mechili to Slonta but the Babini Group had retreated from Mechili during the night. [19]

During 27 January, Australian attempts to attack were met by massed artillery-fire, against which the Australian artillery were rationed to ten rounds per-gun-per-day; the 2/4th Australian Battalion repulsed another battalion-strength counter-attack. [20] A column of Bren carriers of the 6th Australian Cavalry Regiment was sent south to reconnoitre the area where the Italian tanks had been reported and was ambushed by a party of the Babini Group with concealed anti-tank guns and machine guns; four Australians were killed and three taken prisoner. The 11th Hussars found a gap at Chaulan south of Wadi Derna, which threatened the Babini Group and the defenders in Derna with encirclement and Bergonzoli ordered a retirement. The Italians disengaged on the night of 28/29 January before the garrison could be trapped and Babini Group rearguards cratered roads, planted mines and booby-traps and managed to conduct several skilful ambushes, which slowed the British pursuit. [21]

Beda Fomm

5 February

At Benghazi and Beda Fomm, the Babini Group had almost a hundred M13/40 tanks. [12] During the retreat from Benghazi, commanded by Lieutenant-General Annibale Bergonzoli (commander of XXIII Corps) the first convoy reached the area of Beda Fomm, ran into a minefield planted across the road and was engaged by the artillery, anti-tank guns and armoured cars of Combeforce, whose ambush threw the column into confusion. Part of the 10th Bersaglieri tried to advance down the road and others on the flanks. (Combeforce had reached Antelat during the morning and by 12:30 p.m. had observers overlooking the Via Balbia west of Beda Fomm and Sidi Saleh, about 30 mi (48 km) south-west of Antelat and 20 mi (32 km) north of Ajedabia, the rest of the force following on south of the Jebel Akhdar.) [22] The attack of the Bersaglieri had little effect, being unsupported by artillery, most of which was with the rearguard to the north. The vanguard of the Italian retreat had no tanks, few front-line infantry which were prevented by the ambush from manoeuvring and to fight where they stood. [23] [22]

Italian rear-area personnel and civilians tried to escape by driving west off the road into the sand dunes and bogged down. Lorries carrying petrol caught fire and lit the dusk, illuminating targets for the British gunners and giving the tanks en route a mark to drive on. The British artillery was not needed and the crews took about 800 prisoners. [24] Tellera, commanding the rearguard, had to retain part of the Babini Group, rather than send all of it south to reinforce Bergonzoli for the attempts to break through the British blocking position and continue the retreat to Agedabia. The fort at Sceleidima had been garrisoned by the Bignami Group of the 10th Bersaglieri, to block the route towards the north end of the Italian column on the Via Balbia and Tellera detached another thirty tanks from the Babini Group as reinforcement. The breakthrough attempts to the south could not be fully reinforced and the Italians could not expect to be undisturbed by British attacks along the convoy or the Australian advance down the Via Balbia, towards the tail of the column. When the rest of the Babini Group arrived at Beda Fomm, only improvised artillery and infantry groups could support it and without reconnaissance its personnel had little idea of British dispositions. [25]

6 February

The retirement of the 4th Armoured Brigade into laager, led Bergonzoli to believe that the force would concentrate in defence of the roadblock and during the night, he organised an attack down the Via Balbia, to pin down the defenders. A flanking move by the Babini Group eastwards through the desert, just west of a feature known as the Pimple, was intended to get behind Combeforce. On the morning of 6 February, the Babini Group had 16 officers and 2,300 men, twenty-four M13s in the V Tank Battalion "M", twelve of the III Tank Battalion "M" at the rear, twenty-four guns, eighteen anti-tank guns, 320 assorted lorries and other small vehicles. [2] At 8:30 a.m. the Babini Group advanced without artillery support and with no knowledge of the situation beyond the first ridge to the east. [26]

The 7th Support Group, which was left with only the 1st King's Royal Rifle Corps (1st KRRC) and some artillery, was held up at Sceleidima by minefields covered by artillery and the Bignami Group. [27] At dawn on 6 February, the Australians continued their attacks on Benghazi from the north and the British continued to attack at Sceleidima, where Bignami was ordered to retire at 10:00 a.m., keep the British off the rear of the column and send the Babini Group detachment south to reinforce the break-out attempt. [26] [28] On the Via Balbia, the first wave of ten M13s from the Babini Group, advanced slowly at 8:30 a.m. and were surprised when turrets of the British cruisers appeared over a ridge 600 yd (549 m) away. Eight M13s were knocked out and then the British tanks disappeared below the ridge. The British tanks re-appeared over the ridge near the white mosque and the Pimple to knock out another seven M13s. Italian artillery opened fire on the mosque and every operational tank the Babini Group had left advanced towards the Pimple and the mosque. [2]

At 10:30 a.m. another big Italian convoy arrived from the north, escorted by M13s which forced back the British. [29] The escorting tanks of the Babini Group kept the light tanks at a distance but they were still able to inflict damage and sow confusion. [30] The weather turned to rain as more Italian columns arrived near the Pimple and were engaged by the British tanks, wherever there were no Italian tanks to stop them. By noon, forty Italian M13s had been knocked out and only about fifty were left. At 1:00 p.m., the V Tank Battalion "M" engaged British tanks and then the III Tank Battalion "M" arrived and joined in. Three British tanks were knocked out and the British retired, leaving behind several prisoners. The III Battalion then repulsed another attack by twelve British tanks on the 10th Army column between Beda Fomm and the sea. After being ambushed by twenty British Cruiser tanks, all but four of the M13/40s of the VI Tank Battalion "M" were knocked out, only 24 days after arriving in Libya. [2]

The Italian rearguard arrived in the afternoon and the concentration of tanks and artillery enabled the Italians to recapture the Pimple, open the road south and continue the outflanking move to the east. [31] The XXI Tank Battalion "M" arrived late, found itself obstructed by a mine field and was unable attack as more British tanks arrived as night fell and intercepted the column as several Italian vehicles and thirty tanks got past the Pimple. [2] Bergonzoli abandoned attempts to hook round the eastern flank and sent the last of the Babini Group west through the dunes, just as the British tanks had to rearm. [32] Several British tanks pursued the Italians, firing into the convoy, setting vehicles alight, forcing drivers to abandon their vehicles or leave the road for the dunes to the west, where they dodged British artillery-fire and attacks by light tanks, which took 350 prisoners. [33]

7 February

The Babini Group had only about thirty tanks left and Bergonzoli planned to us them to force a passage through Combeforce at dawn, before the British could attack the flanks and rear of the column. [34] The Babini Group was supported by artillery-fire, as soon as it became light enough to see movement by the British anti-tank guns portée. British infantry stayed under cover as they were overrun by the M13s, which concentrated their fire on the British anti-tank guns and British artillery fired on the infantry positions as the Babini Group passed through. After the tanks had moved on, the British infantry resumed fire on Italian infantry following the tanks, to pin them down. [35]

The M13s knocked out all but one anti-tank gun and kept going; the last anti-gun was driven to a flank and fired as the last M13s advanced and knocked out the last tank. On the road, the Italians could hear British tank engines on the flanks, to the rear; in the north the British surrounded another Italian group, just before the 10th Army surrendered. The Beda Fomm area had become a 15 mi (24 km) line of destroyed and abandoned lorries, about a hundred guns, one hundred knocked out or captured tanks and 25,000 prisoners, including Tellera (found mortally wounded in one of the M13s), Bergonzoli and the 10th Army staff. [35] The Babini Group lost more than a hundred and one M13s of which 39, mainly from the XXI Tank Battalion "M", were undamaged. [2]

Aftermath

Analysis

On 15 February, a British analysis found that the Italians had been unable to mass their tanks sufficiently and they had attacked the British piecemeal, which was believed to be because the tanks had been spread through the Italian columns. Prisoners had said that the lack of wireless prevented a tactical reorganisation in the confusion. The VI and XXI Medium battalions in M13s were considered to have shown inferior gunnery while on the move, unlike the III and V Tank Battalion "M"s at Mechili in January; the newer battalions had recently received M13s and possibly were inadequately trained on them. Tests on captured M13s found that armour-piercing shells fired by a 25-pounder field gun at 800 yd (732 m) went straight through the tank; when fired with an instantaneous fuze the shell made a large hole in the armour of one side and with a short-delay fuze shells exploded inside the tank. At 500 yd (457 m) a Boys anti-tank rifle dented the armour. Examination of wrecked tanks showed that a hit on the crew compartment almost always killed all the occupants, although the reason for this was not apparent. [36]

Only a few thousand men of the 10th Army and about nine medium tanks had escaped the disaster in Cyrenaica but the 5th Army had four divisions in Tripolitania and the Italians reinforced the Sirte, Tmed Hassan and Buerat strongholds from Italy, which brought the total of Italian soldiers in Tripolitania to about 150,000 men. [37] In 2001, David French wrote that the Italian forces in Libya experienced a "renaissance" during 1941, when the 101st Motorized Division "Trieste", 102nd Motorized Division "Trento", the 132nd Armored Division "Ariete" arrived with better equipment. Italian anti-tank units performed well during Operation Brevity, Operation Battleaxe and the Ariete Division defeated the 22nd Armoured Brigade at Bir el Gubi on 19 November, during Operation Crusader. [38] In 2003, Ian Walker described the loss of the Ragruppamento Maletti in the Attack on Nibeiwa, the first encounter of Operation Compass, as a disaster which cost the Italians the initiative. The Action at Mechili by the Babini Group on 24 January 1941, showed that Italian armoured forces had more potential than at first appeared, gaining an advantage in their first encounter with British tanks and then withdrawing before they were cut off and enabling the 60th Infantry Division "Sabratha" at Derna to retreat. At Beda Fomm the Babini Group came close to overrunning the British defences, despite the disorganisation caused by the British ambush and being exposed to defeat in detail. [39]

Commemoration

To commemorate the destruction of the V and III Tank Battalion "M"s, 8 February was chosen as Corpus Christi (the Feast of the Body of Christ) of the 32nd Tank Infantry Regiment. [2]

Order of battle

Babini Group, 18 November 1940. Data taken from Christie (1999) unless specified. [6]

Tanks

- I Tank Battalion "M" (M11/39)

- III Tank Battalion "M" (M13/40)

- XXI Tank Battalion "L" (L3)

- LX Tank Battalion "L" (L3)

Infantry

- 1 × Bersaglieri Motorcycle Battalion

Artillery

- 1 × Artillery Group ( Cannone da 75/27 modello 06 guns)

- 1 × Artillery Group (100/17 guns)

1st Libyan Armoured Division

- Babini Group

(Intended structure of the brigade when the division was formed)

Tanks

- I Tank Battalion "M" (M11)

- III Tank Battalion "M" (M13)

- XXI Tank Battalion "L" (L.3)

- LX Tank Battalion "L" (L.3)

Infantry

- 10th Bersaglieri Regiment

- XVI Bersaglieri Motorised Battalion

- XXXIV Bersaglieri Motorised Battalion

- XXXV Bersaglieri Motorcycle Battalion

Artillery

- 12th Artillery Regiment, from the

55th Infantry Division "Savona"

- I/12th Group (twelve × 75/27 guns)

- II/12th Group (twelve × 75/27 guns)

- III/12th Group (twelve × 100/17 guns)

See also

Notes

Footnotes

- ^ Walker 2003, p. 51.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Parri.

- ^ Maresciallo D'Italia Rodolfo Graziani. "N. 1/210045 di prot. Op. Comando carri armati della Libia". Comandante Superiore Forze Armate A.S. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ^ a b Christie 1999, pp. 32, 48.

- ^ a b Walker 2003, p. 61.

- ^ a b Christie 1999, pp. 91, 103.

- ^ Christie 1999, p. 57.

- ^ Playfair 1954, p. 266.

- ^ Playfair 1954, pp. 266–268.

- ^ a b Moorehead 2009, pp. 61–64.

- ^ a b Walker 2003, p. 63.

- ^ a b Walker 2003, pp. 63, 65.

- ^ a b Macksey 1972, pp. 121–123; Playfair 1954, p. 353.

- ^ Long 1952, p. 242.

- ^ Macksey 1972, p. 123.

- ^ Macksey 1972, p. 124.

- ^ Long 1952, pp. 242–245.

- ^ Macksey 1972, pp. 124–127.

- ^ Parri; Playfair 1954, p. 353.

- ^ Long 1952, pp. 245–247, 250.

- ^ Long 1952, pp. 250–253, 255–256.

- ^ a b Macksey 1972, pp. 137, 139.

- ^ Playfair 1954, p. 358.

- ^ Macksey 1972, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Macksey 1972, pp. 142–143.

- ^ a b Playfair 1954, p. 359.

- ^ Macksey 1972, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Macksey 1972, p. 148.

- ^ Macksey 1972, pp. 145–148.

- ^ Playfair 1954, pp. 359–360.

- ^ Playfair 1954, pp. 359–361; Macksey 1972, p. 149.

- ^ Macksey 1972, p. 149.

- ^ Macksey 1972, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Macksey 1972, pp. 150–151.

- ^ a b Playfair 1954, p. 361.

- ^ Harding 1941.

- ^ Sadkovich 1991, p. 293.

- ^ French 2001, p. 219.

- ^ Walker 2003, pp. 65–66.

References

Books

- French, David (2001) [2000]. Raising Churchill's Army: The British Army and the War against Germany 1919–1945. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-924630-4.

- Long, Gavin (1952). To Benghazi (PDF). Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 314648263. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- Macksey, Major Kenneth (1972) [1971]. Beda Fomm: The Classic Victory. Ballantine's Illustrated History of the Violent Century. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-09748-4. OCLC 473687868.

- Moorehead, A (2009) [1944]. The Desert War: The Classic Trilogy on the North African Campaign 1940–43 (Aurum Press ed.). London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 978-1-84513-391-7.

- Playfair, Major-General I. S. O.; et al. (1954). Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East: The Early Successes Against Italy (to May 1941). History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. I. HMSO. OCLC 494123451.

- Walker, Ian W. (2003). Iron Hulls, Iron Hearts: Mussolini's Elite Armoured Divisions in North Africa. Marlborough: Crowood. ISBN 978-1-86126-646-0.

Journals

- Sadkovich, James. J. (1991). "Of Myths and Men: Rommel and the Italians in North Africa". The International History Review. XIII (2): 284–313. doi: 10.1080/07075332.1991.9640582. ISSN 0707-5332. JSTOR 40106368.

Theses

- Christie, H. R. (1999). Fallen Eagles: The Italian 10th Army in the Opening Campaign in the Western Desert, June 1940 – December 1940 (MA). Fort Leavenworth, KS: US Army Command and General Staff College. OCLC 465212715. A116763. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

Websites

- Harding, J. (BGS) (23 February 1941). "Cyrenaica Command Intelligence Summary No. 5 and XIII Corps Intelligence Summary No. 18 and Appendix E, H.Q. Cyrenaica Command Intelligence Summary No. 6 (23 Feb 41)". The National Archives. WO 169/1258. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- Parri, M. "Storia del 32° Rgt. Carri dalla Costituzione del Reggimento fino al termine del Secondo Conflitto Mondiale" [History of the 32nd Armoured Regiment from its Establishment until the end of the Second World War]. www.assocarri.it (in Italian). no date, no ISBN. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

Further reading

- Guglielmi, D. (December 2005). "Autocannoni e portees in Africa Settentrionale" [Armoured Cars and Portées in North Africa]. Storia Militare (in Italian). Parma, Italy: Albertelli Edizioni Speciali: 32–33. ISSN 1122-5289.

- Wavell, A. (26 June 1946). "Archibald Wavell's Despatch on Operations in the Western Desert From 7th December, 1940 to 7th February 1941" (PDF). Supplement to the London Gazette, Number 37628. Retrieved 31 October 2009.

External links

- Babini Group Order of Battle (in Italian)

- Diary of Colonel Emilio Iezzi, Commander, V Tank Battalion "M"

- The Mediterranean and Middle East, volume I, The Early Successes against Italy (to May 1941) Ch 19: Graziani is swept out of Cyrenaica, January–February 1941 (1954)

- Babini Group, An Organizational History