| Franco-Provençal | |

|---|---|

| Arpitan | |

| patous, gagaer, arpəttan | |

| Pronunciation | [paˈto]; [ɡaˈɡæx]; [axpetan] |

| Native to | Italy, France and Switzerland |

| Region | Aosta Valley, Piedmont, Franche-Comté, Savoie, Bresse, Bugey, Dombes, Beaujolais, Dauphiné, Lyonnais, Forez, Romandie |

Native speakers | 157,000 (2013)

[1] 80,000 in France, 70,000 in Italy and 7,000 in Switzerland [2] |

Early forms | |

| Dialects | |

| Latin | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

frp |

| Glottolog |

fran1269 Francoprovencalic

fran1260 Arpitan |

| ELP | Francoprovençal |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAA-j

[5] |

Map of the Franco-Provençal language area:

| |

Franco-Provençal is classified as Definitely Endangered by the UNESCO

Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

Franco-Provençal (also Francoprovençal, Patois or Arpitan) [2] is a language within the Gallo-Romance family, originally spoken in east-central France, western Switzerland and northwestern Italy.

Franco-Provençal has several distinct dialects and is separate from but closely related to neighbouring Romance dialects (the langues d'oïl and the langues d'oc, in France, as well as Rhaeto-Romance in Switzerland and Italy). [a]

Even with all its distinct dialects counted together, the number of Franco-Provençal speakers has been declining significantly and steadily. [6] According to UNESCO, Franco-Provençal was already in 1995 a "potentially endangered language" in Italy and an " endangered language" in Switzerland and France. Ethnologue classifies it as "nearly extinct". [2]

The designation Franco-Provençal (Franco-Provençal: francoprovençâl; French: francoprovençal; Italian: francoprovenzale) dates to the 19th century. In the late 20th century, it was proposed that the language be referred to under the neologism Arpitan (Franco-Provençal: arpetan; Italian: arpitano), and its areal as Arpitania. [7] The use of both neologisms remains very limited, with most academics using the traditional form (often written without the hyphen: Francoprovençal), while language speakers refer to it almost exclusively as patois or under the names of its distinct dialects (Savoyard, Lyonnais, Gaga in Saint-Étienne, etc.). [8]

Formerly spoken throughout the Duchy of Savoy, Franco-Provençal is nowadays (as of 2016) spoken mainly in the Aosta Valley as a native language by all age ranges. [9] All remaining areas of the Franco-Provençal language region show practice limited to higher age ranges, except for Evolène and other rural areas of French-speaking Switzerland. It was also historically spoken in the Alpine valleys around Turin and in two isolated towns ( Faeto and Celle di San Vito) in Apulia. [10]

In France, it is one of the three Gallo-Romance language families of the country (alongside the langues d'oïl and the langues d'oc). Though it is a regional language of France, its use in the country is marginal. Still, organizations are attempting to preserve it through cultural events, education, scholarly research, and publishing.

Classification

Although the name Franco-Provençal suggests it is a bridge dialect between French and the Provençal dialect of Occitan, it is a separate Gallo-Romance language that transitions into the Oïl languages Morvandiau and Franc-Comtois to the northwest, into Romansh to the east, into the Gallo-Italic Piemontese to the southeast, and finally into the Vivaro-Alpine dialect of Occitan to the southwest.

The philological classification for Franco-Provençal published by the Linguasphere Observatory (Dalby, 1999/2000, p. 402) follows:

A philological classification for Franco-Provençal published by Ruhlen (1987, pp. 325–326) is as follows:

History

Franco-Provençal emerged as a Gallo-Romance variety of Latin. The linguistic region comprises east-central France, western portions of Switzerland, and the Aosta Valley of Italy with the adjacent alpine valleys of the Piedmont. This area covers territories once occupied by pre-Roman Celts, including the Allobroges, Sequani, Helvetii, Ceutrones, and Salassi. By the fifth century, the region was controlled by the Burgundians. Federico Krutwig has also suggested a Basque substrate in the toponyms of the easternmost Valdôtain dialect. [11]

Franco-Provençal is first attested in manuscripts from the 12th century, possibly diverging from the langues d'oïl as early as the eighth–ninth centuries (Bec, 1971). However, Franco-Provençal is consistently typified by a strict, myopic comparison to French, and so is characterized as "conservative". Thus, commentators such as Désormaux consider "medieval" the terms for many nouns and verbs, including pâta "rag", bayâ "to give", moussâ "to lie down", all of which are conservative only relative to French. As an example, Désormaux, writing on this point in the foreword of his Savoyard dialect dictionary, states:

The antiquated character of the Savoyard patois is striking. One can note it not only in phonetics and morphology, but also in the vocabulary, where one finds numerous words and directions that clearly disappeared from French. [12]

Franco-Provençal failed to garner the cultural prestige of its three more widely spoken neighbors: French, Occitan, and Italian. Communities where speakers lived were generally isolated from each other because of the mountains. In addition, the internal boundaries of the entire speech area were divided by wars and religious conflicts.

France, Switzerland, the Franche-Comté (part of the Spanish Monarchy), and the duchy, later kingdom, ruled by the House of Savoy politically divided the region. The strongest possibility for any dialect of Franco-Provençal to establish itself as a major language died when an edict, dated 6 January 1539, was confirmed in the parliament of the Duchy of Savoy on 4 March 1540 (the duchy was partially occupied by France since 1538). The edict explicitly replaced Latin (and by implication, any other language) with French as the language of law and the courts (Grillet, 1807, p. 65).

The name Franco-Provençal (franco-provenzale) is due to Graziadio Isaia Ascoli (1878), chosen because the dialect group was seen as intermediate between French and Provençal. Franco-Provençal dialects were widely spoken in their speech areas until the 20th century. As French political power expanded and the "single-national-language" doctrine was spread through French-only education, Franco-Provençal speakers abandoned their language, which had numerous spoken variations and no standard orthography, in favor of the culturally prestigious French.

Origin of the name

Franco-Provençal is an extremely fragmented language, with scores of highly peculiar local variations that never merged over time. The range of dialect diversity is far greater than that found in the langue d'oïl and Occitan regions. Comprehension of one dialect by speakers of another is often difficult. Nowhere is it spoken in a "pure form" and there is not a "standard reference language" that the modern generic label used to identify the language may indicate. This explains why speakers use local terms to name it, such as Bressan, Forèzien, or Valdôtain, or simply patouès ("patois"). Only in recent years have speakers who are not specialists in linguistics become conscious of the language's collective identity.

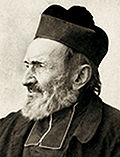

The language region was first recognized in the 19th century during advances in research into the nature and structure of human speech. Graziadio Isaia Ascoli (1829–1907), a pioneering linguist, analyzed the unique phonetic and structural characteristics of numerous spoken dialects. In an article written about 1873 and published later, he offered a solution to existing disagreements about dialect frontiers and proposed a new linguistic region. He placed it between the langues d'oïl group of languages (Franco) and the langues d'oc group (Provençal) and gave Franco-Provençal its name.

Ascoli (1878, p. 61) described the language in these terms in his defining essay on the subject:

Chiamo franco-provenzale un tipo idiomatico, il quale insieme riunisce, con alcuni caratteri specifici, più altri caratteri, che parte son comuni al francese, parte lo sono al provenzale, e non proviene già da una confluenza di elementi diversi, ma bensì attesta sua propria indipendenza istorica, non guari dissimili da quella per cui fra di loro si distinguono gli altri principali tipi neo-latini.

I call Franco-Provençal a type of language that brings together, along with some characteristics which are its own, characteristics partly in common with French, and partly in common with Provençal, and are not caused by a late confluence of diverse elements, but on the contrary, attests to its own historical independence, little different from those by which the principal neo-Latin [Romance] languages distinguish themselves from one another.

Although the name Franco-Provençal appears misleading, it continues to be used in most scholarly journals for the sake of continuity. Suppression of the hyphen between the two parts of the language name in French (francoprovençal) was generally adopted following a conference at the University of Neuchâtel in 1969; [13] however, most English-language journals continue to use the traditional spelling.

The name Romand has been in use regionally in Switzerland at least since 1494, when notaries in Fribourg were directed to write their minutes in both German and Rommant. It continues to appear in the names of many Swiss cultural organizations today. The term "Romand" is also used by some professional linguists who feel that the compound word "Franco-Provençal" is "inappropriate". [14]

A proposal in the 1960s to call the language Burgundian (French: "burgondien") did not take hold, mainly because of the potential for confusion with an Oïl language known as Burgundian, which is spoken in a neighbouring area, known in English as Burgundy ( French: Bourgogne). Other areas also had historical or political claims to such names, especially (Meune, 2007).

Some contemporary speakers and writers prefer the name Arpitan because it underscores the independence of the language and does not imply a union to any other established linguistic group. "Arpitan" is derived from an indigenous word meaning "alpine" ("mountain highlands"). [15] It was popularized in the 1980s by Mouvement Harpitanya, a political organization in the Aosta Valley. [16] In the 1990s, the term lost its particular political context. [17] The Aliance Culturèla Arpitana (Arpitan Cultural Alliance) is advancing the cause for the name "Arpitan" through the Internet, publishing efforts, and other activities. The organization was founded in 2004 by Stéphanie Lathion and Alban Lavy in Lausanne, Switzerland, and is now based in Fribourg. [18] In 2010 SIL adopted the name "Arpitan" as the primary name of the language in ISO 639-3, with "Francoprovençal" as an additional name form. [19]

Native speakers call this language patouès (patois) or nosta moda ("our way [of speaking]"). Some Savoyard speakers call their language sarde. This is a colloquial term used because their ancestors were subjects of the Kingdom of Sardinia ruled by the House of Savoy until Savoie and Haute-Savoie were annexed by France in 1860. The language is called gaga in France's Forez region and appears in the titles of dictionaries and other regional publications. Gaga (and the adjective gagasse) comes from a local name for the residents of Saint-Étienne, popularized by Auguste Callet's story "La légende des Gagats" published in 1866.

Geographic distribution

The historical linguistic domain of the Franco-Provençal language [20] are:

Italy

- Aosta Valley (place name in Valdôtain patois: Val d'Outa; in Italian: Valle d'Aosta; in French: Vallée d'Aoste); excepting the Walser-speaking valley, the villages of Gressoney-Saint-Jean, Gressoney-La-Trinité and Issime ( Lys valley).

- the alpine heights of the Metropolitan City of Turin in the Piedmont basin which includes the following 43 communities: Ala di Stura, Alpette, Balme, Cantoira (Cantoire), Carema (Carême), Castagnole Piemonte, Ceres, Ceresole Reale (Cérisoles), Chialamberto (Chalambert), Chianocco (Chanoux), Coassolo Torinese, Coazze (Couasse), Condove (Condoue), Corio (Corio), Frassinetto (Frasinei), Germagnano (Saint-Germain), Giaglione (Jaillons), Giaveno, Gravere (Gravière), Groscavallo (Groscaval), Ingria, Lanzo Torinese (Lans), Lemie, Locana, Mattie, Meana di Susa (Méan), Mezzenile (Mesnil), Monastero di Lanzo (Moutier), Noasca, Novalesa (Novalaise), Pessinetto, Pont-Canavese, Ribordone (Ribardon), Ronco Canavese (Ronc), Rubiana (Rubiane), Sparone (Esparon), Susa (Suse), Traves, Usseglio (Ussel), Valgioie (Valjoie), Valprato Soana (Valpré), Venaus (Vénaux), Viù (Vieu). Note: The southernmost valleys of Piedmont speak Occitan.

- two enclaves in the Province of Foggia, Apulia region in the southern Apennine Mountains: the villages of Faeto and Celle di San Vito. [21]

France

- the major part of Rhône-Alpes and Franche-Comté regions, which includes the following départements: Jura (southern two-thirds), Doubs (southern third), Haute-Savoie, Savoie, Isère (except the southern edge which traditionally spoke occitan), Rhône, Drôme (extreme north), Ardèche (extreme north), Loire, Ain, and Saône-et-Loire (southern edge).

Switzerland

- most of the officially French-speaking Romandie (Suisse-Romande) part of the country, including the following cantons: Geneva (Genève/Genf), Vaud, the lower part of Valais (Wallis), Fribourg (Freiburg), and Neuchâtel. Note: the remaining parts of Romandie, namely Jura, and the northern valleys of the canton Bern linguistically belong to the langues d'oïl.

Present status

The Aosta Valley is the only region of the Franco-Provençal area where this language is still widely spoken as native by all age ranges of the population. Since 1948 several events have combined to stabilize the language ( Valdôtain dialect) in this region. The constitution of Italy was amended [22] to change the status of the former province to an autonomous region. This gives the Aosta Valley special powers to make its own decisions about certain matters. This resulted in growth in the region's economy and the population increased from 1951 to 1991, improving long-term prospects. Residents were encouraged to stay in the region and they worked to continue long-held traditions.

The language was explicitly protected by a 1991 Italian presidential decree [23] and a national law passed in 1999. [24] Further, a regional law [25] passed by the government in Aosta requires educators to promote knowledge of Franco-Provençal language and culture in the school curriculum. Several cultural groups, libraries, and theatre companies are fostering a sense of ethnic pride with their active use of the Valdôtain dialect as well (EUROPA, 2005).

Paradoxically, the same federal laws do not grant the language the same protection in the Province of Turin because there Franco-Provençal speakers make up less than 15% of the population. Lack of jobs has resulted in their migration from the Piedmont's alpine valleys, and contributed to the language's decline.

Switzerland does not recognize Romand (not be confused with Romansh) as one of its official languages. Speakers live in western cantons where Swiss French predominates; they converse in the dialects mainly as a second language. The use in agrarian daily life is rapidly disappearing. However, in a few isolated places the decline is considerably less steep. This is most notably the case for the Evolène dialect. [26]

Franco-Provençal has had a precipitous decline in France. The official language of the French Republic has been designated as French (article 2 of the Constitution of France). The French government officially recognizes Franco-Provençal as one of the " languages of France", [27] but its constitution bars it from ratifying the 1992 European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (ECRML) that would guarantee certain rights to Franco-Provencal. This language has almost no political support in France and it is associated with generally low social status. This situation affects most regional languages that comprise the linguistic wealth of France. Speakers of regional languages are aging and live in mostly rural areas.

Number of speakers

The Franco-Provençal dialect with the greatest population of active daily speakers is Valdôtain. Approximately 68,000 people speak the language in the Aosta Valley region of Italy, according to reports compiled after the 2003 census. [28] The alpine valleys of the adjacent province of Turin have an estimated 22,000 speakers. The Faetar and Cigliàje dialect is spoken by 1,400 speakers, who live in an isolated pocket of the province of Foggia in the southern Italian Apulia region (figures for Italy: EUROPA, 2005). Beginning in 1951, strong emigration from the town of Celle Di San Vito to Canada established the Cigliàje variety of this dialect in Brantford, Ontario. At its peak, the language was used daily by several hundred people. As of 2012 this community has dwindled to fewer than 50 daily speakers across three generations.

Contrary to official information reported by the European Commission, a poll by the Fondation Émile Chanoux in 2001 [29] revealed that only 15% of all Aosta Valley residents claimed Franco-Provençal as their mother tongue, a substantial reduction to the figures reported on the Italian census 20 years earlier (and used in the 2001 commission report). Some 55.77% of the residents said they know Franco-provençal and 50.53% said they know French, Franco-provençal and Italian. [30] This opened a discussion about the concept of mother tongue when concerning a dialect. The Aosta Valley was confirmed as the only area where Franco-provençal is actively spoken in the early 21st century. [31] A report published by Laval University in Quebec City, [32] which analyzed this data, reports that it is "probable" that the language will be "on the road to extinction" in this region in ten years. The 2009 edition of ethnologue.com [2] (Lewis, 2009) reports that there are 70,000 Franco-Provençal speakers in Italy. However, these figures are derived from the 1971 census.

In rural areas of the cantons of Valais and Fribourg in Switzerland, various dialects are spoken as a second language by about 7,000 residents (figures for Switzerland: Lewis, 2009). In the other cantons of Romandie where Franco-Provençal dialects used to be spoken, they are now all but extinct.

Until the mid-19th century, Franco-Provençal dialects were the most widely spoken language in their domain in France. Today, regional vernaculars are limited to a small number of speakers in secluded towns. A 2002 report by the INED (Institut national d'études démographiques) states that the language loss by generation was 90%, made up of: "the proportion of fathers who did not usually speak to their 5-year-old children in the language that their own father usually spoke in to them at the same age". This was a greater loss than undergone by any other language in France, a loss called "critical". The report estimated that fewer than 15,000 speakers in France were handing down some knowledge of Franco-Provençal to their children (figures for France: Héran, Filhon, & Deprez, 2002; figure 1, 1-C, p. 2).

Linguistic structure

Note: The overview in this section follows Martin (2005), with all Franco-Provençal examples written in accordance with Orthographe de référence B (see "Orthography" section, below).

Typology and syntax

- Franco-Provençal is a synthetic language, as are Occitan and Italian. Most verbs have different endings for person, number, and tenses, making the use of the pronoun optional; thus, two grammatical functions are bound together. However, the second-person singular verb form regularly requires an appropriate pronoun for distinction.

- The standard word order for Franco-Provençal is subject–verb–object (SVO) form in a declarative sentence, for example: Vos côsâds anglès. ("You speak English."), except when the object is a pronoun, in which case the word order is subject–object–verb (SOV). verb–subject–object (VSO) form is standard word order for an interrogative sentence, for example: Côsâds-vos anglès ? ("Do you speak English?")

Morphology

Franco-Provençal has grammar similar to that of other Romance languages.

-

Articles have three forms: definite, indefinite, and partitive. Plural definite articles

agree in gender with the noun to which they refer, unlike French. Partitive articles are used with

mass nouns.

Articles precede women's given names during conversation: la Foëse (Françoise/Frances), la Mya (Marie), la Jeânna (Jeanne/Jane), la Peronne (Pierrette), la Mauriza (Mauricette/Maurisa), la Daude (Claude/Claudia), la Génie (Eugénie/Eugenia); however, articles never precede men's names: Fanfoué (François), Dian (Jean/John), Guste (Auguste), Zèbe (Eusèbe/Eusebius), Ouiss (Louis), Mile (Émile).Articles: Masculine Definite Feminine Definite Masculine Indefinite Feminine Indefinite Singular lo la on na Plural los les des / de des / de -

Nouns are

inflected by number and gender. Inflection by

grammatical number (singular and plural) is clearly distinguished in feminine nouns, but not masculine nouns, where pronunciation is generally identical for those words ending with a vowel.

To assist comprehension of written words, modern orthographers of the language have added an "s" to most plural nouns that is not reflected in speech. For example:

codo (masculine singular): [ˈkodo] [ˈkodu] [ˈkodə],codos (masculine plural): [ˈkodo] [ˈkodu] [ˈkodə] (in Italy, codo is occasionally used for both singular and plural).pôrta (feminine singular): [ˈpɔrtɑ] [ˈpurtɑ],pôrtas (feminine plural): [ˈpɔrte] [ˈpurte] [ˈpɔrtɛ] [ˈpurtɛ] [ˈpɔrtɑ] [ˈpurtɑ] (in Italy, pôrte is occasionally seen).

In general, inflection by grammatical gender (masculine and feminine) is the same as for French nouns; however, there are many exceptions. A few examples follow:

Franco-Provençal Occitan (Provençal) French Piedmontese Italian English la sal (fem.) la sau (fem.) le sel (masc.) la sal (fem.) il sale (masc.) the salt l'ôvra (fem.), la besogne (fem.) l'òbra (fem.), lo trabalh (masc.)

l'œuvre (fem.), la besogne (fem.), le travail (masc.), le labeur (masc.)

ël travaj (masc.) il lavoro (masc.) the work l'ongla (fem.) l'ongla (fem.) l'ongle (masc.) l'ongia (fem.) l'unghia (fem.) the fingernail l'ôlyo (masc.) l'òli (masc.) l'huile (fem.) l'euli (masc.) l'olio (masc.) the oil lo crotâl (masc.), lo vipèro (masc.) la vipèra (fem.) la vipère (fem.) la vipra (fem.) la vipera (fem.) the viper - Subject pronouns agree in person, number, gender, and case. Although the subject pronoun is usually retained in speech, Franco-Provençal – unlike French or English – is a partially pro-drop language ( null subject language), especially in the first-person singular. Masculine and feminine third-person singular pronouns are notable for the extremely wide variation in pronunciation from region to region. Impersonal subjects, such as weather and time, take the neuter pronoun "o" (and/or "el", a regional variant used before a word beginning with a vowel), which is analogous to "it" in English.

- Direct and indirect object pronouns also agree in person, number, gender, and case. However, unlike subject pronouns, third-person singular and plural have neuter forms, in addition to masculine and feminine forms.

- Possessive pronouns and possessive adjectives agree in person, number, gender, and case (masculine singular and plural forms are noteworthy because of their extremely wide variation in pronunciation from area to area).

- Relative pronouns have one invariable form.

- Adjectives agree in gender and number with the nouns they modify.

- Adverbs are invariable; that is, they are not inflected, unlike nouns, verbs, and adjectives.

-

Verbs form three grammatical conjugation classes, each of which are further split into two subclasses. Each

conjugation is different, formed by isolating the

verb stem and adding an ending determined by mood, tense, voice, and number. Verbs are inflected in four

moods:

indicative,

imperative,

subjunctive, and

conditional; and two impersonal moods:

infinitive and

participle, which includes verbal adjectives.

Verbs in Group 1a end in -ar (côsar, "to speak"; chantar, "to sing"); Group 1b end in -ier (mengier, "to eat"); Groups 2a & 2b end in -ir (finir, "to finish"; venir, "to come"), Group 3a end in -êr (dêvêr, "to owe"), and Group 3b end in -re (vendre, "to sell").

Auxiliary verbs are: avêr (to have) and étre (to be).

Phonology

The consonants and vowel sounds in Franco-Provençal:

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i iː | y | u | |

| Close-mid | e | ø | o oː | |

| Mid | ə | |||

| Open-mid | ɛ ɛː | œ | ɔ | |

| Open | a | ɑ ɑː | ||

- Phonetic realizations of / o/, can be frequently realized as [ ø, ɔ, as well as [ œ] in short form when preceding a / j/ or a / w/.

- The sounds / ø, œ/ are mostly phonemic in the dialects of Savoy, Val d'Aosta, and Lyon. [33] [34] [35]

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | ĩ | ũ |

| Mid | ɛ̃ | õ |

| Open | ɑ̃ |

Consonants

| Labial |

Dental/ Alveolar |

Post- alveolar |

Palatal |

Velar/ Uvular | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | voiceless | p | t | c | k | |

| voiced | b | d | ɟ | ɡ | ||

| Affricate | voiceless | ( t͡s) | ( t͡ʃ) | |||

| voiced | ( d͡z) | ( d͡ʒ) | ||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | ||

| voiced | v | z | ʒ | ( ʁ) | ||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ( ŋ) | ||

| Trill | r | |||||

| Lateral | l | ʎ | ||||

| Approximant | plain | j | ||||

| labial | ɥ | w | ||||

- Affricate sounds [ t͡ʃ] and [ d͡ʒ] are mainly present in Fribourg and Valais dialects (often written as chi and gi/ji, occurring before a vowel).

- In Arles, and in some dialects of Hauteville and Savoie, the /r/ phoneme is realized as [ ʁ].

- In the dialects of Savoie and Bresse, phonetic dental sounds [ θ] and [ ð] occur corresponding to palatal sounds / c/ and / ɟ/. These two sounds may also be realized in dialects of Valais, where they correspond to a succeeding / l/ after a voiceless or voiced stop (like cl, gl) they are then realized as [ θ], [ ð].

- A nasal sound [ ŋ] can occur when a nasal precedes a velar stop.

- Palatalizations of /s, k/ can be realized as [ ç, x~ χ in some Savoyard dialects.

- In rare dialects, a palatal lateral /ʎ/ can be realized as a voiced fricative [ ʝ].

- A glottal fricative [ h] occurs as a result of the softening of the allophones of [ ç, x~ χ in Savoie and French-speaking Switzerland.

- In the dialects of Valdôtien, Fribourg, Valais, Vaudois and in some dialects of Savoyard and Dauphinois, realizations of phonemes / c, ɟ/ often are heard as affricate sounds [ t͡s, d͡z. In the dialects of French-speaking Switzerland, Valle d'Aosta, and Neuchâtel, the two palatal stops are realized as the affricates, [ t͡ʃ, d͡ʒ. [36]

- The placement of stressed syllables in the spoken language is a primary characteristic of Franco-Provençal that distinguishes it from French and Occitan. Franco-Provençal words take stress on the last syllable, as in French, or on the penultimate syllable, unlike French.

- Franco-Provençal also preserves final vowel sounds, in particular "a" in feminine forms and "o" in masculine forms (where it is pronounced "ou" in some regions.) The word portar is pronounced [pɔrˈtɑ] or [pɔrˈto], with accent on the final "a" or "o", but rousa is pronounced [ˈruːzɑ], with accent on the "ou".

- Vowels followed by nasal consonants "m" and "n" are normally nasalized in a similar manner to those in French, for example, chantar and vin in Franco-Provençal, and "chanter" and "vin" in French. However, in the largest part of the Franco-Provençal domain, nasalized vowels retain a timbre that more closely approaches the un-nasalized vowel sound than in French, for example, pan [pɑ̃] and vent [vɛ̃] in Franco-Provençal, compared to "pain" [pɛ̃] and "vent" [vɑ̃] in French.

Orthography

Franco-Provençal does not have a standard orthography. Most proposals use the Latin script and four diacritics: the acute accent, grave accent, circumflex, and diaeresis (trema), while the cedilla and the ligature ⟨ œ⟩ found in French are omitted.

- Aimé Chenal and Raymond Vautherin wrote the first comprehensive grammar and dictionary for any variety of Franco-Provençal. Their landmark effort greatly expands upon the work by Jean-Baptiste Cerlogne begun in the 19th century on the Valdôtain (Valdotèn) dialect of the Aosta Valley. It was published in twelve volumes from 1967 to 1982.

- The Bureau régional pour l'ethnologie et la linguistique (BREL) in Aosta and the Centre d'études franco-provençales « René Willien » (CEFP) in Saint-Nicolas, Italy, have created a similar orthography that is actively promoted by their organizations. It is also based on work by Jean-Baptiste Cerlogne, with several modifications.

- An orthographic method called La Graphie de Conflans has achieved fairly wide acceptance among speakers residing in Bresse and Savoy. Since it was first proposed by the Groupe de Conflans of Albertville, France in 1983, it has appeared in many published works. This method perhaps most closely follows the International Phonetic Alphabet, omitting extraneous letters found in other historical and contemporary proposals. It features the use of a combining low line (underscore) as a diacritic to indicate a stressed vowel in the penult when it occurs, for example: toma, déssanta.

- A recent standard entitled Orthographe de référence B (ORB) was proposed by linguist Dominique Stich with his dictionary published by Editions Le Carré in 2003. (This is an emendation of his previous work published by Editions l'Harmattan in 1998.) His standard strays from close representation of Franco-Provençal phonology in favor of following French orthographic conventions, with silent letters and clear vestiges of Latin roots. However, it attempts to unify several written forms and is easiest for French speakers to read. — Note: Stich's dictionary for ORB is noteworthy because it includes neologisms by Xavier Gouvert for things found in modern life, such as: encafâblo for "cell phone" (from encafar, "to put into a pocket"), pignochière for "fast-food" (from pignochiér, "to nibble"), panètes for "corn flakes" (from panet, "maize, corn"), and mâchelyon for "chewing gum".

The table below compares a few words in each writing system, with French and English for reference. (Sources: Esprit Valdôtain (download 7 March 2007), C.C.S. Conflans (1995), and Stich (2003).

| Franco-Provençal | Occitan | Italian | French | Spanish | English | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | Chenal | BREL | Conflans | ORB | Provençal | Standard | Standard | Standard | Standard |

| /kɑ̃/ | quan | can | kan | quand | quand, quora | quando | quand | cuando | when |

| /ˈtʃikɑ/ | tsëca | tchica | tchika | checa | un pauc | un po' | un peu | un poco | a little |

| /tsɑ̃/ | tsan | tsan | tsan | champ | tèrra | campo | champ | campo | field |

| /dʒuˈɑ/ | dzoà | djouà | djoua | juè | jòc | gioco | jeu | juego | game |

| /ˈtʃøvrɑ/ | tseuvra | tcheuvra | tseûvra | chiévra | cabra | capra | chèvre | cabra | goat |

| /ˈfɔʎə/ | foille | foille | fòye | fôlye | fuelha | foglia | feuille | hoja | leaf |

| /ˈføʎə/ | faille | feuille | feûye | felye | filha | figlia | fille | hija | daughter |

| /fɔ̃ˈtɑ̃.ɑ/ | fontana | fontan-a | fontana | fontana | fònt | fontana | fontaine | fuente | wellspring |

| /ˈlɑ̃.ɑ/ | lana | lan-a | lana | lana | lana | lana | laine | lana | wool |

| /siˈlɑ̃sə/ | silence | silanse | silanse | silence | silenci | silenzio | silence | silencio | silence |

| /rəpəˈbløk.ə/ | repeublecca | repebleucca | repebleûke | rèpublica | republica | repubblica | république | república | republic |

Numerals

Franco-Provençal uses a decimal counting system. The numbers "1", "2", and "4" have masculine and feminine forms (Duplay, 1896; Viret, 2006).

0) zérô; 1) yon (masc.), yona / yena (fem.); 2) dos (masc.), does / doves / davè (fem.); 3) três; 4) quatro (masc.), quat / quatrè (fem.); 5) cinq; 6) siéx; 7) sèpt; 8) huét; 9) nô; 10) diéx; 11) onze'; 12) doze; 13) trèze; 14) quatôrze; 15) quinze; 16) sèze; 17) dix-sèpt; 18) dix-huét; 19) dix-nou; 20) vengt; 21) vengt-yon / vengt-et-yona; 22) vengt-dos ... 30) trenta; 40) quaranta; 50) cinquanta; 60) souessanta; 70) sèptanta; 80) huétanta; 90) nonanta; 100) cent; 1000) mila; 1,000,000) on milyon / on milyona.

Many western dialects use a vigesimal (base-20) form for "80", that is, quatro-vingt /katroˈvɛ̃/, possibly due to the influence of French.

Word comparisons

The chart below compares words in Franco-Provençal to those in selected Romance languages, with English for reference.

Between vowels, the Latinate "p" became "v", "c" and "g" became "y", and "t" and "d" disappeared. Franco-Provençal also softened the hard palatized "c" and "g" before "a". This led Franco-Provençal to evolve down a different path from Occitan and Gallo-Iberian languages, closer to the evolutionary direction taken by French.

| Latin | Franco-Provençal | French | Occitan | Catalan | Spanish | Romansh | Piedmontese | Italian | Portuguese | Sardinian | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| clavis | cllâf | clé, clef | clau | clau | llave | clav | ciav | chiave | chave | crai | key |

| cantare | chantar | chanter | cantar | cantar | cantar | c(h)antar | canté | cantare | cantar | cantai | sing |

| capra | chiévra | chèvre | cabra | cabra | cabra | chavra | crava | capra | cabra | craba | goat |

| caseus (formaticus) | tôma/fromâjo | tomme/fromage | formatge | formatge | queso | caschiel | formagg | formaggio | queijo | casu | cheese |

| dies Martis | demârs/mârdi | mardi | dimars | dimarts | martes | mardi(s) | màrtes | martedì | terça-feira | martis | Tuesday |

| ecclesia/basilica | égllése | église/basilique | glèisa | església | iglesia | baselgia | gesia/cesa | chiesa | igreja | cresia | church |

| fratrem | frâre | frère | fraire | germà | hermano | frar | frel | fratello | irmão | frari | brother |

| hospitalis | hèpetâl/hopetâl | hôpital | espital | hospital | hospital | spital/ospidal | ospidal | ospedale | hospital | ospidali | hospital |

| lingua | lengoua | langue, langage | lenga | llengua | lengua | lieunga | lenga | lingua | língua | lingua, limba | language |

| sinister | gôcho/mâladrêt | gauche | esquèrra/senèstra | esquerra | izquierda | saniester/schnester | gàucia | sinistra | esquerda | sa manu manca | left |

| rem/natam/ne gentem | ren | rien | res/ren | res/re | nada | nuot/navot/nöglia | nen/gnente | niente/nulla | nada | nudda | nothing |

| noctem | nuet | nuit | nuèch/nuèit | nit | noche | not(g) | neuit/neucc | notte | noite | noti | night |

| pacare | payér | payer | pagar | pagar | pagar | pagar/pajar | paghé | pagare | pagar | pagai | pay |

| sudor | suor | sueur | susor | suor | sudor | suada | sudor | sudore | suor | suai | sweat |

| vita | via | vie | vida | vida | vida | veta/vita | via/vita | vita | vida | vida | life |

Dialects

Classification of Franco-Provençal dialect divisions is challenging. Each canton and valley uses its own vernacular without standardization. Difficult intelligibility among dialects was noted as early as 1807 by Grillet.

The dialects are divided into eight distinct categories or groups. Six dialect groups comprising 41 dialect idioms for the Franco-Provençal language have been identified and documented by Linguasphere Observatory (Observatoire Linguistique) (Dalby, 1999/2000, pp. 402–403). Only two dialect groups – Lyonnaise and Dauphinois-N. – were recorded as having fewer than 1,000 speakers each. Linguasphere has not listed any dialect idiom as "extinct", however, many are highly endangered. A seventh isolated dialect group, consisting of Faetar (also known as "Cigliàje" or "Cellese"), has been analyzed by Nagy (2000). The Piedmont dialects need further study.

- Dialect Group : Dialect Idiom: (Epicenters / Regional locations)

- Lyonnais: (France)

- 1. Bressan ( Bresse, Ain ( département) west; Revermont, French Jura (département) southwest; Saône-et-Loire east),

- 2. Bugésien ( Bugey, Ain southeast),

- 3. Mâconnais ( Mâcon country),

- 4. Lyonnais-rural (Lyonnais mountains, Dombes, & Balmes)

- 5. Roannais+Stéphanois ( Roanne country, Foréz plain, & Saint-Étienne).

- Dauphinois-N.: (France)

- 1. Dauphinois-Rhodanien ( Rhône River valley, Rhône (département) south, Loire (département) southeast, Ardèche north, Drôme north, Isère west),

- 2. Crémieu ( Crémieu, Isère north),

- 3. Terres-Froides ( Bourbre River valley, Isère central north),

- 4. Chambaran ( Roybon, Isère central south),

- 5. Grésivaudan [& Uissans] (Isère east).

- Savoyard: (France)

- 1. Bessanèis ( Bessans),

- 2. Langrin ( Lanslebourg),

- 3. Matchutin ( Valloire & Ma’tchuta) (1., 2. & 3.: Maurienne country, Arc valley, Savoie south),

- 4. Tartentaise [& Tignard] ( Tarentaise country, Tignes, Savoie east, Isère upper valleys),

- 5. Arly ( Arly valley, Ugine, Savoie north),

- 6. Chambérien ( Chambéry),

- 7. Annecien [& Viutchoïs] ( Annecy, Viuz-la-Chiésaz, Haute-Savoie southwest),

- 8. Faucigneran ( Faucigny, Haute-Savoie southeast),

- 9. Chablaisien+Genevois ( Chablais country & Geneva (canton) hinterlands).

- Franc-Comtois (FrP) [Jurassien-Méridional]: (Switzerland & France)

- 1. Neuchâtelois (Neuchâtel (canton)),

- 2. Vaudois-NW. (Vaud northwest),

- 3. Pontissalien ( Pontarlier & Doubs (département) south),

- 4. Ain-N. ( Ain upper valleys & French Jura),

- 5. Valserine ( Bellegarde-sur-Valserine, Valserine valley, Ain northeast & adjacent French Jura).

- Vaudois: (Switzerland)

- 1. Vaudois-Intracluster (Vaud west),

- 2. Gruyèrienne (Fribourg (canton) west),

- 3. Enhaut ( Château-d'Œx, Pays-d'Enhaut, Vaud east),

- 4. Valaisan (Valais, Valaisan Romand).

- Valdôtain: ( Aosta Valley, Italy)

- 1. Valdôtain du Valdigne ( Dora Baltea upper valley, similar to savoyard Franco-Provençal),

- 2. Aostois ( Aostan valdôtain),

- 3. Valdôtain standard (Dora Baltea middle valley),

- 4. Valpellinois, bossolein and bionassin (Valpelline Great St. Bernard and Bionaz valleys),

- 5. Cognein (upper Cogne valley),

- 6. Valtournain (in Valtournenche valley),

- 7. Ayassin (upper Ayas valley),

- 8. Valgrisein ( Valgrisenche valley),

- 9. Rhêmiard ( Rhêmes valley),

- 10. Valsavarein ( Valsavarenche valley),

- 11. Moyen valdôtain (middle-lower Dora Baltea valley),

- 12. Bas Valdôtain (lower Dora Baltea valley, similar to Piedmontese),

- 13. Champorcherin ( Champorcher valley)

- 14. Fénisan ( Fénis)

- Faetar, Cigliàje: (Italy)

- 1. Faetar & Cigliàje ( Faeto & Celle di San Vito, in Province of Foggia). This variety is also spoken in Brantford, Ontario, Canada by an established emigrant community.

- Piedmont Dialects: (Italy)

- (Note: Comparative analyses of dialect idioms in the Piedmont basin of the Metropolitan City of Turin — from the Val Soana in the north to the Val Sangone in the south — have not been published).

Dialect examples

Several modern orthographic variations exist for all dialects of Franco-Provençal. The spellings and IPA equivalents listed below appear in Martin (2005).

| English | Occitan (Provençal) | Franco-Provençal | Savoyard dialect | Bressan dialect | French |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hello! | Bonjorn ! | Bonjorn ! | [bɔ̃ˈʒu] | [bɔ̃ˈʒø] | Bonjour ! |

| Good night! | Bòna nuech ! | Bôna nuet ! | [bunɑˈne] | [bunɑˈnɑ] | Bonne nuit ! |

| Goodbye! | A reveire ! | A revér ! | [arˈvi] | [arɛˈvɑ] | Au revoir ! |

| Yes | Òc, vòai | Ouè | [ˈwɛ] | [ˈwɛ] | Oui, Ouais |

| No | Non | Nan | [ˈnɑ] | [ˈnɔ̃] | Non, Nan |

| Maybe | Benlèu / Bensai | T-èpêr / Pôt-étre | [tɛˈpɛ] | [pɛˈtetrə] | Peut-être, (P't-être) |

| Please | Se vos plai | S’il vos plét | [sivoˈple] | [sevoˈplɛ] | S'il-vous-plaît |

| Thank you! | Grandmercé, mercé ! | Grant-marci ! | [ɡrɑ̃maˈsi] | [ɡrɑ̃marˈsi] | Merci beaucoup !, [Un] grand merci ! |

| A man | Un òme | Un homo | [on ˈomo] | [in ˈumu] | Un homme |

| A woman | Una frema, una femna | Na fèna | [nɑ ˈfɛnɑ] | [nɑ ˈfɛnɑ] | Une femme |

| The clock | Lo relòtge | Lo relojo | [lo rɛˈloʒo] | [lo rɛˈlodʒu] | L'horloge |

| The clocks | Lei relòtges | Los relojos | [lu rɛˈloʒo] | [lu rɛˈlodʒu] | Les horloges |

| The rose | La ròsa | La rousa | [lɑ ˈruzɑ] | [lɑ ˈruzɑ] | La rose |

| The roses | Lei ròsas | Les rouses | [lɛ ˈruzɛ] | [lɛ ˈruze] | Les roses |

| He is eating. | Manja. | Il menge. | [il ˈmɛ̃ʒɛ] | [il ˈmɛ̃ʒɛ] | Il mange. |

| She is singing. | Canta. | Ele chante. | [lə ˈʃɑ̃tɛ] | [ɛl ˈʃɑ̃tɛ] | Elle chante. |

| It is raining. | Plòu. | O pluvègne. | [o plyˈvɛɲə] | Il pleut. | |

| O brolyasse. | [u brulˈjasə] | Il pleuvine. | |||

| What time is it? | Quant es d'ora ? | Quint’hora est ? | [kɛ̃t ˈørɑ ˈjɛ] | ||

| Quâl’hora est ? | [tjel ˈoʒɑ ˈjə] | Quelle heure est-il ? | |||

| It is 6:30. | Es sièis oras e mieja. | (Il) est siéx hores et demi. | [ˈjɛ siz ˈørɑ e dɛˈmi] | Il est six heures et demie. | |

| Il est siéx hores demi. | [ˈɛjɛ siʒ ˈoʒə dɛˈmi] | ||||

| What is your name? | Coma te dison ? | ’T-il que vos éd niom ? | [ˈtɛk voz i ˈɲɔ̃] | Quel est votre nom ? | |

| Coment que vos vos apelâd ? | [kɛmˈe kɛ ˈvu vu apaˈlo] | Comment vous appelez-vous ? (Comment que vous vous appelez ?) | |||

| I am happy to see you. | Siáu content de vos veire. | Je su bon éso de vos vér. | [ʒə sɛ buˈnezə də vo ˈvi] | Je suis heureux/ravi de vous voir | |

| Je su content de vos vêr. | [ʒɛ si kɔ̃ˈtɛ də vu ˈvɑ] | Je suis content de vous voir. | |||

| Do you speak Patois? | Parlatz patoès ? | Prègiéd-vos patouès ? | [prɛˈʒi vo patuˈe] | Parlez-vous [le] Patois ? | |

| Côsâd-vos patouès ? | [koˈʒo vu patuˈɑ] | Causez vous [le] Patois ? |

Toponyms

Other than in family names, the Franco-Provençal legacy survives primarily in placenames. Many are immediately recognizable, ending in -az, -o(t)z, -uz, -ax, -ex, -ux, -ou(l)x, -aulx, and -ieu(x). These suffixes are vestiges of an old medieval orthographic practice indicating the stressed syllable of a word. In polysyllables, 'z' indicates a paroxytone (stress on penultimate syllable) and 'x' indicates an oxytone (stress on last syllable). So, Chanaz [ˈʃɑnɑ] (shana) but Chênex [ʃɛˈne] (shèné). The following is a list of all such toponyms:

Italy

- Aosta Valley: Bionaz, Champdepraz, Morgex, and Perloz

- Piedmont: Oulx, and Sauze d'Oulx

France

- Ain: Ambérieu-en-Bugey, Ambérieux-en-Dombes, Arbignieu, Belleydoux, Belmont-Luthézieu, Birieux, Boz, Brénaz, Ceyzérieu, Challex, Chanoz-Châtenay, Charnoz-sur-Ain, Chevroux, Civrieux, Cleyzieu, Colomieu, Contrevoz, Conzieu, Cormoz, Courmangoux, Culoz, Cuzieu, Flaxieu, Gex, Hostiaz, Injoux-Génissiat, Izieu, Jujurieux, Lagnieu, Lescheroux, Lochieu, Lompnieu, Léaz, Lélex, Malafretaz, Marboz, Marignieu, Marlieux, Massieux, Massignieu-de-Rives, Meximieux, Mijoux, Misérieux, Montagnieu, Monthieux, Murs-et-Gélignieux, Niévroz, Nurieux-Volognat, Oncieu, Ordonnaz, Ornex, Outriaz, Oyonnax, Parcieux, Perrex, Peyrieu, Peyzieux-sur-Saône, Pirajoux, Pollieu, Prémillieu, Pugieu, Reyrieux, Rignieux-le-Franc, Ruffieu, Saint-André-le-Bouchoux, Saint-André-sur-Vieux-Jonc, Saint-Germain-de-Joux, Saint-Jean-le-Vieux, Saint-Nizier-le-Bouchoux, Saint-Paul-de-Varax, Sault-Brénaz, Seillonnaz, Songieu, Sonthonnax-la-Montagne, Surjoux, Sutrieu, Talissieu, Thézillieu, Torcieu, Toussieux, Trévoux, Vernoux, Versailleux, Versonnex, Vieu, Vieu-d'Izenave, Villieu-Loyes-Mollon, Virieu-le-Grand, Virieu-le-Petit, and Échenevex

- Ardèche: Ajoux, Beaulieu, Boucieu-le-Roi, Boulieu-lès-Annonay, Châteauneuf-de-Vernoux, Colombier-le-Vieux, Coux, Davézieux, Dunière-sur-Eyrieux, Lavilledieu, Le Roux, Les Ollières-sur-Eyrieux, Roiffieux, Saint-Fortunat-sur-Eyrieux, Saint-Jacques-d'Atticieux, Saint-Julien-le-Roux, Saint-Michel-de-Chabrillanoux, Saint-Pierre-sur-Doux, Saint-Étienne-de-Valoux, Satillieu, Talencieux, and Vinzieux

- Doubs: Bolandoz, Champoux, Chevroz, Châteauvieux-les-Fossés, Dampjoux, Deluz, Goux-les-Usiers, Goux-lès-Dambelin, Goux-sous-Landet, Grand'Combe-Châteleu, Granges-Narboz, La Cluse-et-Mijoux, Le Barboux, Le Bélieu, Les Hôpitaux-Vieux, Les Villedieu, Montmahoux, Montécheroux, Reculfoz, Saraz, Doubs, Verrières-de-Joux, Villars-sous-Dampjoux, and Éternoz

- Drôme: Allex, Clérieux, Génissieux, Marsaz, Molières-Glandaz, Montaulieu, Montjoux, Roussieux, Saint-Bardoux, Saint-Bonnet-de-Valclérieux, Solérieux, and Vassieux-en-Vercors

- Haute-Savoie: Alex, Annecy-le-Vieux, Arthaz-Pont-Notre-Dame, Aviernoz, Bernex, Cernex, Chainaz-les-Frasses, Charvonnex, Chavannaz, Chessenaz, Chevenoz, Chênex, Combloux, Copponex, Excenevex, La Clusaz, La Côte-d'Arbroz, La Forclaz, La Muraz, La Vernaz, Marcellaz, Marcellaz-Albanais, Marlioz, Marnaz, Menthonnex-en-Bornes, Menthonnex-sous-Clermont, Monnetier-Mornex, Mont-Saxonnex, Peillonnex, Reyvroz, Saint-Jorioz, Servoz, Seythenex, Seytroux, Vaulx, Veigy-Foncenex, Versonnex, Villaz, Ville-en-Sallaz, Villy-le-Pelloux, Viuz-en-Sallaz, Viuz-la-Chiésaz, and Vétraz-Monthoux

- Isère: Apprieu, Assieu, Beaulieu, Bellegarde-Poussieu, Bilieu, Bossieu, Bourgoin-Jallieu, Bouvesse-Quirieu, Bressieux, Cessieu, Chamagnieu, Charancieu, Charvieu-Chavagneux, Chassignieu, Chavanoz, Cheyssieu, Chélieu, Creys-Mépieu, Crémieu, Dizimieu, Diémoz, Dolomieu, Fitilieu, Granieu, Heyrieux, Jarcieu, La Chapelle-de-Surieu, Les Roches-de-Condrieu, Leyrieu, Lieudieu, Marcieu, Massieu, Meyrieu-les-Étangs, Moidieu-Détourbe, Moissieu-sur-Dolon, Monsteroux-Milieu, Montagnieu, Montalieu-Vercieu, Montseveroux, Notre-Dame-de-Vaulx, Optevoz, Ornacieux, Oz, Parmilieu, Pisieu, Porcieu-Amblagnieu, Proveysieux, Quincieu, Romagnieu, Saint-André-le-Gaz, Saint-Jean-de-Vaulx, Saint-Jean-le-Vieux, Saint-Julien-de-Raz, Saint-Martin-le-Vinoux, Saint-Pierre-de-Bressieux, Saint-Pierre-de-Méaroz, Saint-Romain-de-Surieu, Saint-Siméon-de-Bressieux, Saint-Victor-de-Cessieu, Sardieu, Sermérieu, Siccieu-Saint-Julien-et-Carisieu, Siévoz, Soleymieu, Succieu, Tignieu-Jameyzieu, Varacieux, Vatilieu, Vaulx-Milieu, Vernioz, Vertrieu, Veyssilieu, Vignieu, Villemoirieu, Virieu, and Vénérieu

- Jura: Bonlieu, Choux, Châtel-de-Joux, Courlaoux, Fontainebrux, Fraroz, Lajoux, Les Bouchoux, Marnoz, Menétrux-en-Joux, Molamboz, Moutoux, Onoz, Pagnoz, Ponthoux, Recanoz, Saffloz, Vannoz, Vertamboz, Villevieux, and Vulvoz

- Loire: Andrézieux-Bouthéon, Aveizieux, Bussy-Albieux, Champdieu, Chazelles-sur-Lavieu, Cuzieu, Doizieux, Grézieux-le-Fromental, Jonzieux, La Bénisson-Dieu, Lavieu, Marcoux, Mizérieux, Nandax, Nervieux, Nollieux, Pouilly-sous-Charlieu, Précieux, Saint-Haon-le-Vieux, Saint-Hilaire-sous-Charlieu, Saint-Jean-Soleymieux, Saint-Nizier-sous-Charlieu, Soleymieux, Unieux, and Épercieux-Saint-Paul

- Savoie: Aillon-le-Vieux, Allondaz, Avressieux, Avrieux, Barberaz, Chamoux-sur-Gelon, Chanaz, Chindrieux, Cohennoz, Conjux, Drumettaz-Clarafond, Entremont-le-Vieux, Frontenex, Jongieux, La Giettaz, La Motte-Servolex, Loisieux, Marcieux, Meyrieux-Trouet, Motz, Ontex, Ruffieux, Saint-Jean-de-Couz, Saint-Pierre-de-Genebroz, Saint-Thibaud-de-Couz, Sonnaz, Verthemex, and Villaroux

- Rhône: Affoux, Ambérieux, Brussieu, Cailloux-sur-Fontaines, Chassieu, Civrieux-d'Azergues, Colombier-Saugnieu, Condrieu, Courzieu, Décines-Charpieu, Fleurieu-sur-Saône, Fleurieux-sur-l'Arbresle, Grézieu-la-Varenne, Grézieu-le-Marché, Jarnioux, Joux, Lissieu, Meyzieu, Ouroux, Poleymieux-au-Mont-d'Or, Quincieux, Rillieux-la-Pape, Saint-Cyr-le-Chatoux, Saint-Pierre-de-Chandieu, Soucieu-en-Jarrest, Sourcieux-les-Mines, Toussieu, Vaulx-en-Velin, Ville-sur-Jarnioux, and Vénissieux

- Saône-et-Loire: Chalmoux, Clux, Lux, Marly-sur-Arroux, Ouroux-sous-le-Bois-Sainte-Marie, Ouroux-sur-Saône, Pontoux, Pouilloux, Rigny-sur-Arroux, Saint-Bonnet-de-Joux, Saint-Didier-sur-Arroux, Saint-Nizier-sur-Arroux, Saint-Pierre-le-Vieux, Thil-sur-Arroux, Toulon-sur-Arroux, Vendenesse-sur-Arroux, Verjux, and Étang-sur-Arroux

Switzerland

- Fribourg: Chésopelloz, Crésuz, Ferpicloz, La Brillaz, La Folliaz, La Sonnaz, Neyruz, Noréaz, Pont-en-Ogoz, Prez-vers-Noréaz, Sévaz, Vaulruz, Villaz-Saint-Pierre, and Vuisternens-en-Ogoz

- Geneva: Bardonnex, Bernex, Choulex, Collex-Bossy, Laconnex, Le Grand-Saconnex, Onex, Perly-Certoux, Thônex, and Troinex

- Neuchâtel: Brot-Plamboz and La Chaux-du-Milieu

- Valais: Arbaz, Collombey-Muraz, Dorénaz, Evionnaz, Lax, Massongex, Mex, Nax, Nendaz, Vernayaz, Vex, Veysonnaz, Vionnaz, Vérossaz, and Vétroz

- Vaud: Arnex-sur-Nyon, Arnex-sur-Orbe, Bex, Bioley-Magnoux, Bioley-Orjulaz, Borex, Champtauroz, Chanéaz, Cheseaux-Noréaz, Chevroux, Château-d'Œx, Chéserex, Founex, La Sarraz, Mauraz, Mex, Mutrux, Neyruz-sur-Moudon, Palézieux, Paudex, Penthalaz, Penthaz, Penthéréaz, Puidoux, Rennaz, Rivaz, Ropraz, Saint-Légier-La Chiésaz, Saint-Prex, Saubraz, Signy-Avenex, Suscévaz, Tolochenaz, and Trélex

Literature

A long tradition of Franco-Provençal literature exists, although no prevailing written form of the language has materialized. An early 12th-century fragment containing 105 verses from a poem about Alexander the Great may be the earliest known work in the language. Girart de Roussillon, an epic with 10,002 lines from the mid-12th century,[[[Girart de Roussillon#Romance#{{{section}}}|contradictory]]] has been asserted to be Franco-Provençal. It certainly contains prominent Franco-Provençal features, although the editor of an authoritative edition of this work claims that the language is a mixture of French and Occitan forms. [37] A significant document from the same period containing a list of vassals in the County of Forez also is not without literary value.

Among the first historical writings in Franco-Provençal are legal texts by civil law notaries that appeared in the 13th century as Latin was being abandoned for official administration. These include a translation of the Corpus Juris Civilis (known as the Justinian Code) in the vernacular spoken in Grenoble. Religious works also were translated and conceived in Franco-Provençal dialects at some monasteries in the region. The Legend of Saint Bartholomew is one such work that survives in Lyonnais patois from the 13th century.

Marguerite d'Oingt ( c. 1240–1310), prioress of a Carthusian nunnery near Mionnay (France), composed two remarkable sacred texts in her native Lyonnais dialect, in addition to her writings in Latin. The first, entitled Speculum ("The Mirror"), describes three miraculous visions and their meanings. The other work, Li Via seiti Biatrix, virgina de Ornaciu ("The Life of the Blessed Virgin Beatrix d'Ornacieux"), is a long biography of a nun and mystic consecrated to the Passion whose faith lead to a devout cult. This text contributed to the beatification of the nun more than 500 years later by Pope Pius IX in 1869. [38] A line from the work in her dialect follows: [39]

- § 112 : « Quant vit co li diz vicayros que ay o coventavet fayre, ce alyet cela part et en ot mout de dongiers et de travayl, ancis que cil qui gardont lo lua d'Emuet li volissant layssyer co que il demandavet et que li evesques de Valenci o volit commandar. Totes veys yses com Deus o aveyt ordonat oy se fit. »

Religious conflicts in Geneva between Calvinist Reformers and staunch Catholics, supported by the Duchy of Savoy, brought forth many texts in Franco-Provençal during the early 17th century. One of the best known is Cé qu'è lainô ("The One Above"), which was composed by an unknown writer in 1603. The long narrative poem describes l'Escalade, a raid by the Savoyard army that generated patriotic sentiments. It became the unofficial national anthem of the Republic of Geneva. The first three verses follow below (in Genevois dialect) [40] with a translation:

|

|

|

|

|

|

Several writers created satirical, moralistic, poetic, comic, and theatrical texts during the era that followed, which indicates the vitality of the language at that time. These include: Bernardin Uchard (1575–1624), author and playwright from Bresse; Henri Perrin, comic playwright from Lyon; Jean Millet (1600?–1675), author of pastorals, poems, and comedies from Grenoble; Jacques Brossard de Montaney (1638–1702), writer of comedies and carols from Bresse; Jean Chapelon (1647–1694), priest and composer of more than 1,500 carols, songs, epistles, and essays from Saint-Étienne; and François Blanc dit la Goutte (1690–1742), writer of prose poems, including Grenoblo maléirou about the great flood of 1733 in Grenoble. 19th century authors include Guillaume Roquille (1804–1860), working-class poet from Rive-de-Gier near Saint-Chamond, Joseph Béard dit l'Éclair (1805–1872), physician, poet, and songwriter from Rumilly, and Louis Bornet (1818–1880) of Gruyères. Clair Tisseur (1827–1896), architect of Bon-Pasteur Church in Lyon, published many writings under the pen name "Nizier du Puitspelu". These include a popular dictionary and humorous works in Lyonnaise dialect that have reprinted for more than 100 years. [41]

Amélie Gex (1835–1883) wrote in her native patois as well as French. She was a passionate advocate for her language. Her literary efforts encompassed lyrical themes, work, love, tragic loss, nature, the passing of time, religion, and politics, and are considered by many to be the most significant contributions to the literature. Among her works are: Reclans de Savoué ("Echos from Savoy", 1879), Lo cent ditons de Pierre d'Emo ("One Hundred Sayings by Pierre du Bon-Sens", 1879), Poesies ("Poems", 1880), Vieilles gens et vieilles choses: Histoires de ma rue et de mon village ("Old people and old things: Stories from my street and from my village", 1889), Fables (1898), and Contio de la Bova ("Tales from the Cowshed").

The writings of the abbé Jean-Baptiste Cerlogne (1826–1910) are credited with reestablishing the cultural identity of the Aosta Valley. His early poetry includes: L'infan prodeggo (1855), Marenda a Tsesalet (1856) and La bataille di vatse a Vertosan (1858); among his scholarly works are: Petite grammaire du dialecte valdotain (1893), Dictionnaire du dialecte valdôtain (1908) and Le patois valdotain: son origine littéraire et sa graphie (1909). The Concours Cerlogne Archived 9 January 2006 at the Wayback Machine – an annual event named in his honor – has focused thousands of Italian students on preserving the region's language, literature, and heritage since 1963.

At the end of the 19th century, regional dialects of Franco-Provençal were disappearing due to the expansion of the French language into all walks of life and the emigration of rural people to urban centers. Cultural and regional savant societies began to collect oral folk tales, proverbs, and legends from native speakers in an effort that continues to today. Numerous works have been published.

Prosper Convert (1852–1934), the bard of Bresse; Louis Mercier (1870–1951), folk singer and author of more than twelve volumes of prose from Coutouvre near Roanne; Just Songeon (1880–1940), author, poet, and activist from La Combe, Sillingy near Annecy; Eugénie Martinet (1896–1983), poet from Aosta; and Joseph Yerly (1896–1961) of Gruyères whose complete works were published in Kan la têra tsantè ("When the earth sang"), are well known for their use of patois in the 20th century. Louis des Ambrois de Nevache, from Upper Susa Valley, transcribed popular songs and wrote some original poetry in local patois. There are compositions in the current language on the album Enfestar, an artistic project from Piedmont [42]

The first comic book in a Franco-Provençal dialect, Le rebloshon que tyouè! ("The cheese that killed!"), from the Fanfoué des Pnottas series by Félix Meynet, appeared in 2000. [43] Two popular works from The Adventures of Tintin [44] [45] and one from the Lucky Luke series [46] were published in Franco-Provençal translations for young readers in 2006 and 2007.

See also

Explanatory notes

- ^ For details on the question of linguistic classification see Gallo-Romance, Gallo-Italic, Questione Ladina.

Citations

- ^ Franco-Provençal at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d "Arpitan". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 19 October 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ a b Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian (24 May 2022). "Glottolog 4.8 - Oil". Glottolog. Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 11 November 2023.

- ^ Norme in materia di tutela delle minoranze linguistiche storiche (in Italian), Italian parliament, 15 December 1999, archived from the original on 2 May 2012, retrieved 8 September 2017

- ^ "f" (PDF). The Linguasphere Register. p. 165. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ^ "Paesaggio Linguistico in Svizzera" [Switzerland's Linguistic Landscape]. Ufficio Federale di Statistica (in Italian). 2000. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ^ A derivation from arpa " alpine pasture", see Pichard, Alain (2 May 2009). "Nos ancêtres les Arpitans" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 July 2011., 24 Heures, Lausanne.

- ^ Gasquet-Cyrus, Médéric (14 February 2018), Auzanneau, Michelle; Greco, Luca (eds.), "Frontières linguistiques et glossonymie en zone de transition: le cas du patois de Valjouffrey", Dessiner les frontières, Langages, Lyon: ENS Éditions, ISBN 978-2-84788-983-3, archived from the original on 28 April 2021, retrieved 16 November 2020

- ^ Site du Centre d'études francoprovençales : "Au temps de Willien : les ferments de langue" Archived 27 June 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Enrico Allasino; Consuelo Ferrier; Sergio Scamuzzi; Tullio Telmon (2005). "LE LINGUE DEL PIEMONTE" (PDF). IRES. 113: 71. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2020 – via Gioventura Piemontèisa.

- ^ Krutwig, F. (1973). Les noms pré-indoeuropéens en Val-d'Aoste. Le Flambeau, no. 4, 1973., in: Henriet, Joseph (1997). La Lingua Arpitana. Quaderni Padani, Vol. III, no. 11, May–June 1997. pp. 25–30. .pdf Archived 6 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine (in Italian).

- ^ Constantin & Désormaux, 1982.

- ^ Marzys, 1971.

- ^ Dalby, 1999/2000, p. 402.

- ^ Bessat & Germi, 1991.

- ^ J. Harriet (1974), "L'ethnie valdôtaine n'a jamais existe... elle n'est que partie de l'ethnie harpitane" in La nation Arpitane Archived 9 July 2012 at archive.today, image of original article posted at Arpitania.eu, 12 January 2007.

- ^ Pichard, Alain (2 May 2009). "Nos ancêtres les Arpitans" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 July 2011., 24 Heures, Lausanne.

- ^ Michel Rime, "L'afére Pecârd, c'est Tintin en patois vaudois", Quotidien (Lausanne), 24 heures, 19 March 2007; p. 3.

- ^ Documentation for ISO 639 identifier: frp Archived 6 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 11 March 2013.

- ^ see: Jochnowitz, George (1973).

- ^ There are various hypotheses about their origins, possibly dating from 1200–1400, e.g. remnants of troops of Charles d'Anjou, according to Michele Melillo, "Intorno alle probabili sedi originarie delle colonie francoprovenzali di Celle e Faeto", Revue de Linguistique Romaine, XXIII, (1959), pp. 1–34, or Waldensian refugees according to Pierre Gilles, Histoire ecclesiastique des églises reformées recueillies en quelques Valées de Piedmont, autrefois appelées Vaudoises, Paris, 1643, p. 19.

- ^ Italian constitutional law: Legge costituzionale 26 febbraio 1948, n. 4, "Statuto speciale per la Valle d'Aosta" ( Parlamento Italiano, Legge 1948, n. 4 Archived 27 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ Italian presidential decree: Decreto presidenziale della Repubblica del 20 novembre 1991, "Norme in materia di tutela delle minoranze linguistiche", Articolo 2.

- ^ Italian federal law: Legge 15 dicembre 1999, n. 482, "Norme in materia di tutela delle minoranze linguistiche storiche", pubblicata nella Gazzetta Ufficiale n. 297 del 20 dicembre 1999, Articolo 2, ( Parlamento Italiano, Legge 482 Archived 29 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ "Conseil de la Vallée - Loi régionale 1er août 2005, n. 18 - Texte en vigueur". Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ "Eat Healthy, Eat Well". Archived from the original on 5 March 2010. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ "Langue française et langues de France". Archived from the original on 10 December 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ Sondage linguistique de la Fondation Archived 20 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine Émile Chanoux.

- ^ Fondation Émile Chanoux: Sondage Archived 7 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Assessorat de l'éducation et la culture - Département de la surintendance des écoles, Profil de la politique linguistique éducative, Le Château éd., 2009, p. 20.

- ^ Alessandro Barbero, Une Vallée d'Aoste bilingue dans une Europe plurilingue, Aoste (2003).

- ^ TLFQ: Vallée d'Aoste Archived 11 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Hauff (2016)

- ^ Viret (2021)

- ^ Kasstan (2015)

- ^ Stich (1998)

- ^ Price, 1998.

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia, See: Beatrix: VI. Blessed Beatrix of Ornacieux Archived 2 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Blumenfeld-Kosinski, Renate (1997). The Writings of Margaret of Oingt, Medieval Prioress and Mystic. (From series: Library of Medieval Women). Cambridge: D.S. Brewer. ISBN 0-85991-442-9.

- ^ Cé qu'è lainô Archived 23 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Complete text of 68 verses in Franco-Provençal and French.

- ^ "Tout sur la langue des gones", Lyon Capitale, N° 399, 30 October 2002.

- ^ Soundcloud: Enfestar. "Album Enfestar, Blu l'azard". Soundcloud. Archived from the original on 18 November 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ^ Meynet, Félix (Illustrations) & Roman, Pascal (Text). Le rebloshon que tyouè !. (Translation in Savoyard dialect.) Editions des Pnottas, 2000. ISBN 2-940171-14-9.

- ^ " Hergé" (Remi, Georges) (2006). Lé Pèguelyon de la Castafiore (" The Castafiore Emerald", from The Adventures of Tintin series). Meune, Manuel & Josine, Trans. (Translation in Bressan dialect, Orthography: La Graphie de Conflans). Brussels, Belgium: Casterman Editions. ISBN 2-203-00930-6.

- ^ " Hergé" (Remi, Georges) (2006). L'Afére Pecârd (" The Calculus Affair", from The Adventures of Tintin series). (Translation in mixed Franco-Provençal dialects, Orthography: ORB). Brussels, Belgium: Casterman Editions. ISBN 2-203-00931-4.

- ^ " Achdé" (Darmenton, Hervé); Gerra, Laurent; & " Morris" (Bevere, Maurice de) (2007). Maryô donbin pèdu ("The Noose", from the Lucky Luke series. Translation in Bressan dialect.) Belgium: Lucky Comics. ISBN 2-88471-207-0.

General and cited sources

- Abry, Christian et al. "Groupe de Conflans" (1994). Découvrir les parlers de Savoie. Conflans (Savoie): Centre de la Culture Savoyarde. This work presents of one of the commonly used orthographic standards

- Aebischer, Paul (1950). Chrestomathie franco-provençale. Bern: Éditions A. Francke S.A.

- Agard, Frederick B. (1984). A Course in Romance Linguistics: A Diachronic View. (Vol. 2). Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 0-87840-089-3

- Ascoli, Graziadio Isaia (1878). Schizzi Franco-provenzali. Archivio glottologico italiano, III, pp. 61–120. Article written about 1873.

- Bec, Pierre (1971). Manuel pratique de philologie romane. (Tome 2, pp. 357 et seq.). Paris: Éditions Picard. ISBN 2-7084-0288-9 A philological analysis of Franco-Provençal; the Alpine dialects have been particularly studied.

- Bessat, Hubert & Germi, Claudette (1991). Les mots de la montagne autour du Mont-Blanc. Grenoble: Ellug. ISBN 2-902709-68-4

- Bjerrome, Gunnar (1959). Le patois de Bagnes (Valais). Stockholm: Almkvist and Wiksell.

- Brocherel, Jules (1952). Le patois et la langue francaise en Vallée d’Aoste. Neuchâtel: V. Attinger.

- Centre de la Culture Savoyard, Conflans (1995). Écrire le patois: La Graphie de Conflans pour le Savoyard. Taninges: Éditions P.A.O. .pdf Archived 10 January 2006 at the Wayback Machine (in French)

- Cerlogne, Jean-Baptiste (1971). Dictionnaire du patois valdôtain, précédé de la petite grammaire. Geneva: Slatkine Reprints. (Original work published, Aosta: Imprimérie Catholique, 1907)

- Chenal, Aimé (1986). Le franco-provençal valdôtain: Morphologie et syntaxe. Quart: Musumeci. ISBN 88-7032-232-7

- Chenal, Aimé & Vautherin, Raymond (1967–1982). Nouveau dictionnaire de patois valdôtain. (12 vol.). Aoste : Éditions Marguerettaz.

- Chenal, Aimé & Vautherin, Raymond (1984). Nouveau dictionnaire de patois valdôtain; Dictionnaire français-patois. Quart: Musumeci. ISBN 88-7032-534-2

- Constantin, Aimé & Désormaux, Joseph (1982). Dictionnaire savoyard. Marseille: Éditions Jeanne Laffitte. (Originally published, Annecy: Société florimontane, 1902). ISBN 2-7348-0137-X

- Cuaz-Châtelair, René (1989). Le Franco-provençal, mythe ou réalité'. Paris, la Pensée universelle, pp. 70. ISBN 2-214-07979-3

- Cuisenier, Jean (Dir.) (1979). Les sources régionales de la Savoie: une approche ethnologique. Alimentation, habitat, élevage, agriculture.... (re: Abry, Christian: Le paysage dialectal.) Paris: Éditions Fayard.

- Dalby, David (1999/2000). The Linguasphere Register of the World's Languages and Speech Communities. (Vol. 2). (Breton, Roland, Pref.). Hebron, Wales, UK: Linguasphere Press. ISBN 0-9532919-2-8 See p. 402 for the complete list of 6 groups and 41 idioms of Franco-Provençal dialects.

- Dauzat, Albert & Rostaing, Charles (1984). Dictionnaire étymologique des noms de lieux en France. (2nd ed.). Paris: Librairie Guénégaud. ISBN 2-85023-076-6

- Devaux, André; Duraffour, A.; Dussert, A.-S.; Gardette, P.; & Lavallée, F. (1935). Les patois du Dauphiné. (2 vols.). Lyon: Bibliothèque de la Faculté catholique des lettres. Dictionary, grammar, & linguistic atlas of the Terres-Froides region.

- Duch, Célestin & Bejean, Henri (1998). Le patois de Tignes. Grenoble: Ellug. ISBN 2-84310-011-9

- Dunoyer, Christiane (2016). Le francoprovençal. Transmission, revitalisation et normalisation. Introduction aux travaux. "Actes de la conférence annuelle sur l’activité scientifique du Centre d’études francoprovençales René Willien de Saint-Nicolas, le 7 novembre 2015". Aosta, pp. 11–15.

- Duraffour, Antonin; Gardette, P.; Malapert, L. & Gonon, M. (1969). Glossaire des patois francoprovençaux. Paris: CNRS Éditions. ISBN 2-222-01226-0

- Elsass, Annie (Ed.) (1985). Jean Chapelon 1647–1694, Œuvres complètes. Saint-Étienne: Université de Saint-Étienne.

- Escoffier, Simone (1958). La rencontre de la langue d'Oïl, de la lange d'Oc, et de francoprovençal entre Loire et Allier. Publications de l'Institut linguistique romane de Lyon, XI, 1958.

- Escoffier, Simone & Vurpas, Anne-Marie (1981). Textes littéraires en dialecte lyonnais. Paris: CNRS Éditions. ISBN 2-222-02857-4

- EUROPA (European Commission) (2005). Francoprovençal in Italy, The Euromosaic Study. Last update: 4 February 2005.

- Favre, Christophe & Balet, Zacharie (1960). Lexique du Parler de Savièse. Romanica Helvetica, Vol. 71, 1960. Bern: Éditions A. Francke S.A.

- Gardette, l'Abbé Pierre, (1941). Études de géographie morphologique sur les patois du Forez. Mâcon: Imprimerie Protat frères.

- Gex, Amélie (1986). Contes et chansons populaires de Savoie. (Terreaux, Louis, Intro.). Aubenas: Curandera. ISBN 2-86677-036-6

- Gex, Amélie (1999). Vieilles gens et vieilles choses: Histoires de ma rue et de mon village. (Bordeaux, Henry, Pref.). Marseille: Éditions Jeanne Laffitte. (Original work published, Chambéry: Dardel, 1924). ISBN 2-7348-0399-2

- Gossen, Charles Théodore (1970). La scripta para-francoprovençale, Revue de linguistique romane 34, p. 326–348.

- Grasset, Pierre & Viret, Roger (2006). Joseph Béard, dit l'Eclair : Médecin des pauvres, Poète patoisant, Chansonnier savoyard. (Terreaux, Louis, Pref.). Montmelian: La Fontaine de Siloé. ISBN 2-84206-338-4

- Grillet, Jean-Louis (1807). Dictionnaire historique, littéraire et statistique des départements du Mont-Blanc et du Léman. Chambéry: Librairie J.F. Puthod.

- Joze Harietta ( Seudónimo de Joseph Henriet), La lingua arpitana : con particolare riferimento alla lingua della Val di Aosta, Tip. Ferrero & Cie. die Romano Canavese, 1976, 174 p.

- Hauff, Tristan (2016). Le français régional de la Vallée d'Aoste: Aspects sociolinguistiques et phonologiques (Masters). Universitetet i Oslo. Archived from the original on 26 January 2023. Retrieved 3 April 2023.[ better source needed]

- Héran, François; Filhon, Alexandra; & Deprez, Christine (2002). Language transmission in France in the course of the 20th century. Population & Sociétés. No. 376, February 2002. Paris: INED-Institut national d’études démographiques. ISSN 0184-7783. Monthly newsletter in English, from INED Archived 22 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Hoyer, Gunhild & Tuaillon, Gaston (2002). Blanc-La-Goutte, poète de Grenoble: Œuvres complètes. Grenoble: Centre alpin et rhodanien d'ethnologie.

- Humbert, Jean (1983). Nouveau glossaire genevois. Genève: Slatkine Reprints. (Original work published, Geneva: 1852). ISBN 2-8321-0172-0

- Iannàccaro, Gabriele & Dell'Aquila, Vittorio (2003). "Investigare la Valle d’Aosta: metodologia di raccolta e analisi dei dati" Archived 19 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine. In: Caprini, Rita (ed.): "Parole romanze. Scritti per Michel Contini", Alessandria: Edizioni Dell'Orso

- Jochnowitz, George (1973). Dialect Boundaries and the Question of Franco-Provençal. Paris & The Hague: Mouton de Gruyter & Co. ISBN 90-279-2480-5

- Kattenbusch, Dieter (1982), Das Frankoprovenzalische in Süditalien: Studien zur synchronischen und diachronischen Dialektologie (Tübinger Beiträge zur Linguistik), Tübingen, Germany: Gunter Narr Verlag. ISBN 3-87808-997-X

- Kasstan, Jonathan and Naomi Nagy, eds. 2018. Special issue: "Francoprovencal: Documenting Contact Varieties in Europe and North America." International Journal of the Sociology of Language 249.

- Kasstan, Jonathan Richard (December 2015). "Lyonnais (Francoprovençal)". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 45 (3): 349–355. doi: 10.1017/S0025100315000250.

- Martin, Jean-Baptiste & Tuaillon, Gaston (1999). Atlas linguistique et ethnographique du Jura et des Alpes du nord (Francoprovençal Central) : La maison, l'homme, la morphologie. (Vol. 3). Paris: CNRS Éditions. ISBN 2-222-02192-8 (cf. Savoyard dialect).

- Martin, Jean-Baptiste (2005). Le Francoprovençal de poche. Chennevières-sur-Marne: Assimil. ISBN 2-7005-0351-1

- Martinet, André (1956). La Description phonologique avec application au parler franco-provençal d'Hauteville (Savoie). Genève: Librairie Droz / M.J. Minard.

- Marzys, Zygmunt (Ed.) (1971). Colloque de dialectologie francoprovençale. Actes. Neuchâtel & Genève: Faculté des Lettres, Droz.

- Melillo, Michele (1974), Donde e quando vennero i francoprovenzali di Capitanata, "Lingua e storia in Puglia"; Siponto, Italy: Centro di Studi pugliesi. pp. 80–95

- Meune, Manuel (2007). Le franco(-)provençal entre morcellement et quête d’unité : histoire et état des lieux. Québec: Laval University. Article in French from TLFQ Archived 7 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Minichelli, Vincenzo (1994). Dizionario francoprovenzale di Celle di San Vito e Faeto. (2nd ed.). (Telmon, Tullio, Intro.). Alessandria: Edizioni dell'Orso. ISBN 88-7694-166-5

- Morosi, Giacomo (1890–92), Il dialetto franco-provenzale di Faeto e Celle, nell'Italia meridionale, "Archivio Glottologico Italiano", XII. pp. 33–75

- Nagy, Naomi (2000). Faetar. Munich: Lincom Europa. ISBN 3-89586-548-6

- Nelde, Peter H. (1996). Euromosaic: The production and reproduction of the minority language groups in the European Union. Luxembourg: European Commission. ISBN 92-827-5512-6 See: EUROPA, 2005.

- Nizier du Puitspelu (pen name of Tisseur, Clair) (2008). Le Littré de la Grand'Côte : à l'usage de ceux qui veulent parler et écrire correctement. Lyon: Éditions Lyonnaises d'Art et d'Histoire. ISBN 2-84147-196-9 (Original work published, Lyon: Juré de l'Académie/Académie du Gourguillon, 1894, reprint 1903). Lyonnaise dialect dictionary and encyclopedia of anecdotes and idiomatic expressions, pp. 353.

- Pierrehumbert, William (1926). Dictionnaire historique du parler neuchâtelois et suisse romand. Neuchâtel: Éditions Victor Attinger.

- Price, Glanville (1998). Encyclopedia of the Languages of Europe. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-19286-7

- Ursula Reutner: 'Minor' Gallo-Romance Languages. In: Lebsanft, Franz/Tacke, Felix: Manual of Standardization in the Romance Languages. Berlin: de Gruyter (Manuals of Romance Linguistics 24), 773–807, ISBN 9783110455731.

- Ruhlen, Merritt (1987). A Guide to the World's Languages. (Vol. 1: Classification). Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1250-6 Author of numerous articles on language and linguistics; Language Universals Project, Stanford University.

- Schüle, Ernest (1978), Histoire et évolution des parler francoprovençaux d'Italie, in: AA. VV, "Lingue e dialetti nell'arco alpino occidentale; Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Torino", Torino, Italy: Centro Studi Piemontesi.

- Stich, Dominique (2003). Dictionnaire francoprovençal / français, français / francoprovençal : Dictionnaire des mots de base du francoprovençal : Orthographe ORB supradialectale standardisée. (Walter, Henriette, Preface). Thonon-les-Bains: Éditions Le Carré. ISBN 2-908150-15-8 This work includes the current orthographic standard for the language.

- Stich, Dominique (1998). Parlons francoprovençal : une langue méconnue. Paris: L'Harmattan. ISBN 2-7384-7203-6. This work includes the former orthographic standard, Orthographe de référence A (ORA).

- Tuaillon, Gaston (1988). Le Franco-provençal, Langue oubliée. in: Vermes, Geneviève (Dir.). Vingt-cinq communautés linguistiques de la France. (Vol. 1: Langues régionales et langues non territorialisées). Paris: Éditions l’Harmattan. pp. 188–207.

- Tuallion, Gaston (2002). La littérature en francoprovençal avant 1700. Grenoble: Ellug. ISBN 2-84310-029-1

- Villefranche, Jacques Melchior (1891). Essai de grammaire du patois Lyonnais. Bourg: Imprimerie J. M. Villefranche.

- Viret, Roger (2001). Patois du pays de l'Albanais : Dictionnaire savoyard-français (2e éd ed.). Cran-Gevrier: L'Echevé du Val-de-Fier. ISBN 2-9512146-2-6. Dictionary and grammar for the dialect in the Albanais region, which includes Annecy and Aix-les-Bains.

- Viret, Roger (2021). "Dictionnaire Français - Savoyard: Comportant plusieurs variantes de la langue savoyarde" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- Vurpas, Anne-Marie (1993). Le Parler lyonnais. (Martin, Jean-Baptiste, Intro.) Paris: Éditions Payot & Rivages. ISBN 2-86930-701-2

- Wartburg, Walter von (1928–2003). Französisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch. ("FEW"). (25 vol.). Bonn, Basel & Nancy: Klopp, Helbing & Lichtenhahn, INaLF/ATILF. Etymological dictionary of Gallo-Roman languages and dialects.

External links

- Arpitan Cultural Alliance, International Federation

- Francoprovencal.org Le site du francoprovençal

- Centre d'Études Francoprovençales of Saint-Nicolas, Aosta Valley

- On-line directory regularly updated

- Google Maps, Precise Map of Arpitania

- [1] Precise Map of Arpitania and Occitania in Italy and Switzerland

- ALMURA: Atlas linguistique multimédia de la région Rhône-Alpes et des régions limitrophes — Multimedia website from Stendhal University-Grenoble 3 with MP3 audio clips of more than 700 words and expressions by native speakers grouped in 15 themes by village. The linguistic atlas demonstrates the transition from Franco-Provençal phonology in the north to Occitan phonology in the south. (select: ATLAS)

- L'Atlas linguistique audiovisuel du Valais romand — Multimedia website from the University of Neuchâtel with audio and video clips of Franco-Provençal speakers from the canton of Valais, Switzerland.

- Les Langues de France en chansons: N'tra Linga e Chanfon — Multimedia website with numerous audio clips of native Franco-Provençal speakers singing traditional songs. Select: TRAINS DIRECTS → scroll to: Francoprovençal.