| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Political rise

29th President of the United States

Presidential campaigns

Controversies

|

||

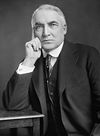

During his time in office, President Warren G. Harding appointed four members of the Supreme Court of the United States: Chief Justice William Howard Taft, and Associate Justices George Sutherland, Pierce Butler, and Edward Terry Sanford.

William Howard Taft nomination

During the 1920 election campaign, William Howard Taft supported the Republican ticket, Harding (by then a senator) and Massachusetts Governor Calvin Coolidge; they were elected. [1] Taft was among those asked to come to the president-elect's home in Marion, Ohio, to advise him on appointments, and the two men conferred there on December 24, 1920. By Taft's later account, after some conversation, Harding casually asked if Taft would accept appointment to the Supreme Court; if Taft would, Harding would appoint him. Taft had a condition for Harding—having served as president, and having appointed two of the present associate justices and opposed Brandeis, he could accept only the chief justice position. Harding made no response, and Taft in a thank-you note reiterated the condition and stated that Chief Justice White had often told him he was keeping the position for Taft until a Republican held the White House. In January 1921, Taft heard through intermediaries that Harding planned to appoint him, if given the chance. [2]

White by then was in failing health, but made no move to resign when Harding was sworn in on March 4, 1921. [3] Taft called on the chief justice on March 26, and found White ill, but still carrying on his work and not talking of retiring. [4] White did not retire, dying in office on May 19, 1921. Taft issued a tribute to the man he had appointed to the center seat, and waited and worried if he would be White's successor. Despite widespread speculation Taft would be the pick, Harding made no quick announcement. [5] Taft was lobbying for himself behind the scenes, especially with the Ohio politicians who formed Harding's inner circle. [6]

It later emerged that Harding had also promised former Utah senator George Sutherland a seat on the Supreme Court, and was waiting in the expectation that another place would become vacant. [a] [7] Harding was also considering a proposal by Justice William R. Day to crown his career by being chief justice for six months before retiring. Taft felt, when he learned of this plan, that a short-term appointment would not serve the office well, and that once confirmed by the Senate, the memory of Day would grow dim. After Harding rejected Day's plan, Attorney General Harry Daugherty, who supported Taft's candidacy, urged him to fill the vacancy, and he named Taft on June 30, 1921. [5] [8] The Senate confirmed Taft the same day, 61–4, without any committee hearings and after a brief debate in executive session, thereby fulfilling Taft's lifelong ambition to become Chief Justice of the United States. Taft drew the objections of three progressive Republicans and one southern Democrat, [b] [9] though the roll call of the vote has never been made public. [10] Taft received his commission immediately and was sworn in on July 11, becoming the first and to date only person to serve both as president and chief justice, [11] remaining in this office until 1930.

George Sutherland nomination

On September 1, 1922, Justice John Hessin Clarke sent a letter to President Harding announcing his intention to resign from the Court. Harding was interested in showing his support for the growing American West, and was determined to pick a nominee from that region. Thus, on September 5, 1922, Harding nominated former Utah Senator George Sutherland to the seat. That same day, Sutherland was confirmed by a voice vote among his colleagues in the United States Senate, and received his commission. [8]

Clarke, who had been dissatisfied with his experience as a Justice, informed Sutherland, that the latter was embarking on "a dog's life" [12]

Pierce Butler nomination

Justice William R. Day resigned from the Court on November 13, 1922. Eight days later, on November 21, 1922, Harding nominated Pierce Butler. Butler was confirmed by the United States Senate on December 21, 1922, by a vote of 61–8. [8]

Although he was supported by Chief Justice Taft, Butler's opposition to "radical" and "disloyal" professors at the University of Minnesota (where he had served on the Board of Regents) made him a controversial Supreme Court nominee. Senator-elect Henrik Shipstead of Butler's home state opposed him, as did Progressive Senator Robert M. La Follette of Wisconsin. Also against his confirmation were labor activists, some liberal newspapers ( The New Republic and The Nation), and the Ku Klux Klan. However, with the support of prominent Roman Catholics, fellow lawyers (the Minnesota State Bar Association strongly endorsed him), and business groups (especially railroad companies), as well as Minnesota's other senator, Knute Nelson, he was confirmed by a wide margin of 61 to 8. The senators who voted against Butler comprised five Democrats ( Walter F. George, William J. Harris, J. Thomas Heflin, Morris Sheppard, and Park Trammell) and three Republicans (Robert M. La Follette Sr., Peter Norbeck, and George W. Norris). He took his seat on the Court on January 2, 1923.

Edward Terry Sanford nomination

Justice Mahlon Pitney retired from the Court on December 31, 1922, after suffering a stroke. On January 24, 1923, Harding nominated Edward Terry Sanford of the United States District Court for the Middle District of Tennessee to replace Pitney. Sanford was confirmed by the United States Senate on January 29, 1923, by a voice vote. [8] As of 2023, Sanford is the last sitting district court judge to be elevated to the Supreme Court.

Names mentioned

Following is a list of individuals who were mentioned in various news accounts and books as having been considered by Harding for a Supreme Court appointment:

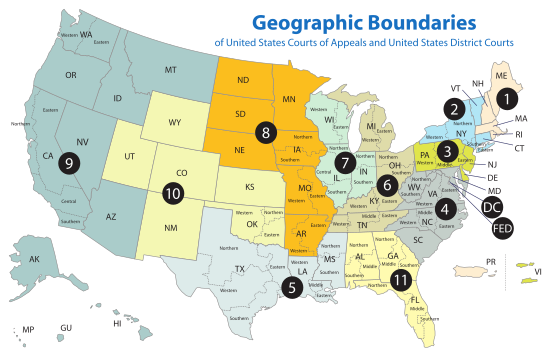

United States Courts of Appeals

-

Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

- Charles Hough (1858–1927) [13]

- Martin Manton (1880-1946) [14]

-

Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit

- Francis E. Baker (1860-1924) [15]

United States District Courts

- Learned Hand (1872–1961) – Judge, United States District Court for the Southern District of New York [14]

- Edward Terry Sanford (1865–1930) – Judge, United States District Court for the Middle District of Tennessee and United States District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee (Nominated and Confirmed) [8]

State Supreme Courts

- Robert von Moschzisker (1870–1939) – Chief Justice, Supreme Court of Pennsylvania [16]

- Benjamin Cardozo (1870–1938) – Judge, New York Court of Appeals (Later nominated by President Herbert Hoover and Confirmed) [13] [14]

Academics

- Harlan Fiske Stone (1872–1946) – Dean of Columbia Law School (Later Nominated by President Calvin Coolidge and Confirmed) [8] [14]

Other backgrounds

- William Howard Taft (1857–1930) – Former President of the United States (Nominated and Confirmed) [8]

- George Sutherland (1862–1942) – Private attorney; former Senator from Utah (Nominated and Confirmed) [8]

- Pierce Butler (1866–1939) – Private attorney (Nominated and Confirmed) [8]

- John W. Davis (1873–1955) – Private attorney; former United States Solicitor General under Wilson and 1924 Democratic presidential candidate [14]

See also

References

- ^ Pringle vol 2, p. 949.

- ^ Gould 2014, pp. 166–168.

- ^ Gould 2014, p. 168.

- ^ Pringle vol 2, p. 956.

- ^ a b Pringle vol 2, pp. 957–959.

- ^ Anderson 2000, p. 345.

- ^ Trani & Wilson, pp. 48–49.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Supreme Court Nominations, 1789–present, senate.gov.

- ^ Gould 2014, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Report on Supreme Court nominees 1789–2005, Congressional Research Service, page 41.

-

^ Gould, Louis L. (February 2000).

Taft, William Howard. Random House.

ISBN

978-0-679-80358-4. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

{{ cite book}}:|work=ignored ( help) - ^ Quoted in Joel Francis Paschal, Mr. Justice Sutherland: A Man Against the State (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951), p. 114.

- ^ a b Kaufman, Andrew L (2000). Cardozo. Harvard University Press. pp. 172–173. ISBN 978-0-674-00192-3.

- ^ a b c d e Danelski, David J (5 November 1980). A Supreme Court Justice Is Appointed. Greenwood Press (CT). ISBN 978-0-313-22652-6.

- ^ 'Successor Today Will Be Named by Harding This Week: Name of Pierce Butler Added to Those Under Consideration – Justice Pitney May Be Retired'; The Bristol Herald, November 21, 1922, p. 2

- ^ 'Harding Greets Justice from Keystone State – Significance Is Attached to Conference'; The Cincinnati Enquirer, December 12, 1922, p. 5

- ^ Sutherland was appointed to the high court in 1922.

- ^ The Republicans were Hiram Johnson of California, William E. Borah of Idaho and La Follette of Wisconsin. The Democrat was Thomas E. Watson of Georgia.

Sources and further reading

- Anderson, Donald F. (Winter 2000). "Building National Consensus: The Career of William Howard Taft". University of Cincinnati Law Review. 68: 323–356.

- Gould, Lewis L. (2014). Chief Executive to Chief Justice:Taft Betwixt the White House and Supreme Court. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-2001-2.

- Pringle, Henry F. (1939). The Life and Times of William Howard Taft: A Biography. Vol. 2. vol 2 covers the presidency after 1910 & Supreme Court

- Trani, Eugene P.; Wilson, David L. (1977). The Presidency of Warren G. Harding. American Presidency. The Regents Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0152-3.