Kingdom of Hawaii

The Kingdom of Hawaii lasted from 1795 until its overthrow in 1893 with the fall of the House of Kalakaua. [1]

House of Kamehameha

The House of Kamehameha (Hale O Kamehameha), or the Kamehameha dynasty, was the reigning Royal Family of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi, beginning with its founding by Kamehameha I in 1795 and ending with the deaths of Kamehameha V in 1872 and William Charles Lunalilo in 1874. [2]

The origins of the House of Kamehameha can be traced to half brothers, Kalaniʻōpuʻu and Keōua. Kalaniʻōpuʻu's father was Kalaninuiʻīamamao while Keōua's father was Kalanikeʻeaumoku, both sons of Keaweʻīkekahialiʻiokamoku. [3] They shared a common mother, Kamakaʻīmoku. Both brothers served Alapaʻinui, the ruling King of Hawaii Island. Hawaiian genealogy notes that Keōua may not have been Kamehameha's biological father, and that Kahekili II might have been his biological father. [3] [4] Regardless, Kamehameha I's descent from Keawe remains intact through his mother, Kekuʻiapoiwa II, a granddaughter of Keawe. Keōua acknowledged him as his son and this relationship is recognized by official genealogies. [3]

The traditional mele chant of Keaka, wife of Alapainui, indicates that Kamehameha I was born in the month of ikuwā (winter) around November. [5] It is also said that Kamehameha was born during the passing of Haley's comet. In Hawaiian culture a comet indicated an important birth. [6] Hawaiian prophecy said that this baby would one day unite the islands by defeating all current chiefs. [6] Alapai gave the young Kamehameha to his wife Keaka and her sister Hākau to care for after the ruler discovered the boy had lived. [7] [8] Samuel Kamakau, wrote, "It was during the time of the warfare among the chiefs of [the island of] Hawaii which followed the death of Keawe, chief over the whole island (Ke-awe-i-kekahi-aliʻi-o-ka-moku) that Kamehameha I was born". However, his general dating was challenged. [9] Abraham Fornander wrote, "when Kamehameha died in 1819 he was past eighty years old. His birth would thus fall between 1736 and 1740, probably nearer the former than the latter". [10] William De Witt Alexander lists the birth date as 1736. [11] He was first named Paiea but took the name Kamehameha, meaning "The very lonely one" or "The one set alone". [12] [13]

Kamehameha's uncle Kalaniʻōpuʻu raised him after Keōua's death. Kalaniʻōpuʻu ruled Hawaii as did his grandfather Keawe. He had advisors and priests. When word reached the ruler that chiefs were planning to murder the boy, he told Kamehameha:

"My child, I have heard the secret complaints of the chiefs and their mutterings that they will take you and kill you, perhaps soon. While I am alive they are afraid, but when I die they will take you and kill you. I advise you to go back to Kohala." "I have left you the god; there is your wealth." [3]

After Kalaniʻōpuʻu's death, Kīwalaʻō took his father's place as first born and ruled the island while Kamehameha became the religious authority. Some chiefs supported Kamehameha and war soon broke out to overthrow Kīwalaʻō. After multiple battles the king was killed and envoys sent for the last two brothers to meet with Kamehameha. Keōua and Kaōleiokū arrived in separate canoes. Keōua came to shore first where a fight broke out and he and all aboard were killed. Before the same could happen to the second canoe, Kamehameha intervened. In 1793 Captain George Vancouver sailed from Britain and presented the Union Flag to Kamehameha, who was still in the process of uniting the islands into a single state; the Union Jack flew unofficially as the flag of Hawaii until 1816, [14] including during a brief spell of British rule after Kamehameha ceded Hawaii to Vancouver in 1794.

By 1795, Kamehameha had conquered all but one of the main islands. For his first royal residence, the new King built the first western-style structure in the Hawaiian Islands, known as the " Brick Palace". [15] The location became the seat of government for the Hawaiian Kingdom until 1845. [16] [17] The king commissioned the structure to be built at Keawa'iki point in Lahaina, Maui. [18] Two ex-convicts from Australia's Botany Bay penal colony built the home. [19] It was begun in 1798 and was completed after 4 years in 1802. [20] [21] The house was intended for Kaʻahumanu, [22] but she refused to live in the structure and resided instead in an adjacent, traditional Hawaiian-styled home. [18]

Kamehameha I had many wives but held two in the highest regard. Keōpūolani was the highest ranking aliʻi of her time [23] and mother to his sons, Liholiho and Kauikeaouli. Kaʻahumanu was his favorite. Kamehameha I died in 1819, succeeded by Liholiho. [24]

Kamehameha II

After Kamehameha I's death, Liholiho left Kailua for a week and returned to be crowned king. At the lavish ceremony attended by commoners and nobles he approached the circle of chiefs, as Kaʻahumanu, the central figure in the group and Dowager Queen, said, "Hear me O Divine one, for I make known to you the will of your father. Behold these chiefs and the men of your father, and these your guns, and this your land, but you and I shall share the realm together". Liholiho agreed officially, which began a unique system of dual-government consisting of a King and co-ruler similar to a regent. [25] Kamehameha II shared his rule with his stepmother, Kaʻahumanu. She defied Hawaiian kapu by dining with the young king, separating the sexes during meals, leading to the end of the Hawaiian religion. Kamehameha II died, along with his wife, Queen Kamāmalu in 1824 on a state visit to England, succumbing to measles. He was King for 5 years. [26]

The couple's remains were returned to Hawaii by Boki. Aboard the ship The Blond his wife Liliha and Kekūanāoʻa were baptized as Christians. Kaʻahumanu also converted and became a powerful Christian influence on Hawaiian society until her death in 1832. [27] Since the new king was only 12 years old, Kaʻahumanu was now senior ruler and named Boki as her Kuhina Nui.

Boki left Hawaii on a trip to find sandalwood to cover a debt and was lost at sea. His wife, Liliha took the governorship of Maui and unsuccessfully attempted to whip up a revolt against Kaʻahumanu, who upon Boki's departure, had installed Kīnaʻu as a co-governor. [27]

Kamehameha III

Kauikeaouli was the second son of Kamehameha I and was born in Keauhou Bay on the island of Hawai'i. [28] Kauikeaouli's birthdate is not explicitly known but many historians place his birth on March 17, 1814. He was about 14 years younger than his brother Liholiho (Kemehameha II). [28] After his birth, Kuakini refused to take him because Kauikeaouli appeard to be lifeless. [29] However, it was declared that the baby would live by a prophet of another chief. They cleaned the baby and put him on a sacred area where the seer fanned him and sprinkled him with water while reciting a prayer. [29] As a result, the baby started to move and make sounds. Kaikioewa was chosen as the baby's guardian and took him away to be raised in a remote location.

Kauikeaouli became the King after the death of his brother in 1824. Kamehameha III began the writing of Hawaii's first formal laws and created a governmental structure. The action was prompted from increasing threat of colonization by foreign countries who were intrigued the strategic geographical location of the islands in the Pacific Ocean. [30] Kamehameha III was advised by a William Richards, a former missionary. William Richards travelled to the United States in an attempt to learn more about Western politics and government structure. He taught Kamehameha III his findings and together they created the first constitution of Hawaii in 1840. [30] Kamehameha III also enacted several laws that recognized human rights and a new new system for land ownership called Mahele. [31] Another major political decision made was the move of the capital from Lahaina to Honolulu where it still holds the title. [32]

In 1843, there was a five month period in which British captain Lord George Paulet pressed Kamehameha III into giving control of the islands to him. [33] Kamehameha III wrote a letter to London informing them of Paulet's actions. Great Britain then reestablished the islands independence on July 31, 1843. [33] It was on this day that Kamehameha III uttered what became the Hawaiian motto, " Ua Mau ke Ea o ka ʻĀina i ka Pono," meanning, "The life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness." The day became a national holiday known as Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea. [34]

Kamehameha III was married to Queen Kalama on February 14, 1837. Kamehameha had one son with his mistress Jane Lahilahi who survived to adulthood named Albert Edward Kūnuiakea. He had two kids with Queen Kalama that both died young: Prince Keaweaweʻulaokalani I and Prince Keaweaweʻulaokalani II. [35] Alexander Liholiho, Kamehameha III's nephew, was taken in by the King and pronounced as the heir to the Hawaiian throne. [36] In 1854 Alexander Liholiho became king as a result of a sudden death of Kamehameha III, likely by stroke. [35]

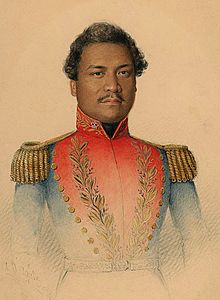

Kamehameha IV

Kamehameha III's adopted son, Alexander Liholiho, was born on February 9, 1834 in the capital of the country, Honolulu. It was 21 later when he took the throne and became Kamehameha IV. His education took place at the Chiefs' Childrens' School and was taught French by Protestant missionaries. [37] The princes did not have an overall happy experience at the school often being sent to bed hungry. [38] Liholiho left the school when he was 14 and began studying law. In his late teens, Liholiho began traveling with his brother, Lot Kapuāiwa, in an attempt to make Hawaii's presence as an independent nation known. Among the places they travelled were the United States, France, and Panama. [37] After a 1949 French attack by Admiral de Tromelin, Liholiho was tasked with trying to improve relations with France. Liholiho and Kapuaiwa were accompanied by Gerrit P. Judd to France with hopes of a treaty being signed. [39] [37] They ultimately failed after three months in France and returned to the islands. Following his return from France he was appointed to Kamehameha III's privy council in 1852. [40]

After taking the throne in 1855, Kamehameha IV's main goal was to stop United States influence on the country. He almost immediately put a stop to the annexation of Hawaii to the United States. [38] The annexation negotiations had been set into motion by Kamehameha III. In 1856 Kamehameha IV had an Anglican wedding with Emma Rooke. Emma Rook was the great grand niece of King Kamehameha I and was a part of the ali'i class. [38] Queen Emma had a very pro-British outlook due to her adoptive parents who were British. In 1858 the Queen and ing had their first and only child Prince Albert Edward Kauikeaouli Kaleiopapa a Kamehameha. The prince had a short life but was described as a very kind and cheerful child. During the years of his child's life, Kamehameha IV established the Anglican church in Hawaii. [38] His son died in 1862. Originally the cause of death for the prince was suspected to be meningitis but now it is believed to have been appendicitis. [41] In the years following the death of his child Kamehameha IV blamed himself for the death. As a result the Queen and the King made healthcare a big part of their reign because they thought diseases like leprosy and influenza were declining the Hawaiian population. The king's proposed healthcare plan was struck down because of a previous healthcare plan that had been set up in the Constitution of 1852 written by Kamehameha III. [38]

The King's rule came to an end on November 30, 1863 when he died from chronic asthma. [42] The King had been experiences deteriorating health for several months before the tragic passing. Kamehameha IV was succeeded by his brother Lot who became Kamehameha V. Queen Emma remained involved in politics until she ultimately lost the race to become the Kingdom's ruling monarch to David Kalakaua.

| This is the sandbox page where you will draft your initial Wikipedia contribution.

If you're starting a new article, you can develop it here until it's ready to go live. If you're working on improvements to an existing article, copy only one section at a time of the article to this sandbox to work on, and be sure to use an edit summary linking to the article you copied from. Do not copy over the entire article. You can find additional instructions here. Remember to save your work regularly using the "Publish page" button. (It just means 'save'; it will still be in the sandbox.) You can add bold formatting to your additions to differentiate them from existing content. |

Article Draft

Lead

Article body

References

- ^ Siler, Julia Flynn (January 2012). Lost Kingdom: Hawaii's Last Queen, the Sugar Kings and America's First Imperial Adventure. Atlantic Monthly Press. pp. 220–. ISBN 978-0-8021-2001-4.

- ^ Homans, Margaret; Munich, Adrienne (2 October 1997). Remaking Queen Victoria. Cambridge University Press. pp. 147–. ISBN 978-0-521-57485-3.

- ^ a b c d Kanahele, George H.; Kanahele, George S. (1986). Pauahi: The Kamehameha Legacy. Kamehameha Schools Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-87336-005-0.

- ^ Dibble, Sheldon (1843). History of the Sandwich Islands. [With a map.]. Press of the Mission Seminary. pp. 54–.

- ^ Hawaiian Historical Society (1936). Annual Report of the Hawaiian Historical Society. The Hawaiian Historical Society. p. 15.

- ^ a b Morrison, Susan Keyes (2003-08-31). Kamehameha: The Warrior King of Hawaii. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2700-7.

- ^ I-H3, Halawa Interchange to Halekou Interchange, Honolulu: Environmental Impact Statement. 1973. p. 483.

- ^ Taylor, Albert Pierce (1922). under hawaiian skies. p. 79.

- ^ Kamakau 1992, p. 66.

- ^ Fornander, Abraham (1880). Stokes, John F. G. (ed.). An Account of the Polynesian Race: Its Origins and Migrations, and the Ancient History of the Hawaiian People to the Times of Kamehameha I. Vol. 2. London: Trübner & Company. p. 136.

- ^ Alexander, William De Witt (1891). A brief history of the Hawaiian people. American Book Co. p. 324.

- ^ Noles, Jim (2009). Pocketful of History: Four Hundred Years of America-One State Quarter at a Time. Perseus Books Group. pp. 296–. ISBN 978-0-7867-3197-8.

- ^ Goldberg, Jake; Hart, Joyce (2007). Hawai'i. Marshall Cavendish. pp. 128–. ISBN 978-0-7614-2349-2.

- ^ "Flag of Hawaii | United States state flag". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ Planet, Lonely; Benson, Sara; Balfour, Amy C.; Karlin, Adam; Skolnick, Adam; Stiles, Paul; Ver Berkmoes, Ryan (1 August 2013). Lonely Planet Hawaii. Lonely Planet Publications. pp. 732–. ISBN 978-1-74321-788-7.

- ^ Bendure, Glenda; Friary, Ned (2008). Lonely Planet Maui. Lonely Planet. pp. 244–. ISBN 978-1-74104-714-1.

- ^ Ring, Trudy; Watson, Noelle; Schellinger, Paul (5 November 2013). The Americas: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. pp. 315–. ISBN 978-1-134-25930-4.

- ^ a b Lahaina Watershed Flood Control Project: Environmental Impact Statement. 2004. p. 214.

- ^ Budnick, Rich (1 January 2005). Hawaii's Forgotten History: 1900–1999: The Good...The Bad...The Embarrassing. Aloha Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-944081-04-4.

- ^ Foster, Jeanette (17 July 2012). Frommer's Maui 2013. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 144–. ISBN 978-1-118-33145-3.

- ^ Kirch, Patrick Vinton (1 January 1997). Feathered Gods and Fishhooks: An Introduction to Hawaiian Archaeology and Prehistory. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 318–. ISBN 978-0-8248-1938-5.

- ^ Thompson, David; Griffith, Lesa M.; Conrow, Joan (14 July 2006). Pauline Frommer's Hawaii. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 284–. ISBN 978-0-470-06984-4.

- ^ Wong, Helen; Rayson, Ann (1987). Hawaii's Royal History. Bess Press. pp. 69–. ISBN 978-0-935848-48-9.

- ^ Ariyoshi, Rita (2009). Hawaii. National Geographic Books. pp. 29–35. ISBN 978-1-4262-0388-6.

- ^ Kuykendall, Ralph Simpson (1 January 1938). The Hawaiian Kingdom. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 64–. ISBN 978-0-87022-431-7.

- ^ Ariyoshi, Rita (2009). Hawaii. National Geographic Books. pp. 29–35. ISBN 978-1-4262-0388-6.

- ^ a b Garrett, John (1 January 1982). To Live Among the Stars: Christian Origins in Oceania. editorips@usp.ac.fj. pp. 52–. ISBN 978-2-8254-0692-2.

- ^

a

b Kam, Ralph Thomas; Duarte-Smith, Ashlie (2018-11).

"Determining the Birth Date of Kauikeaouli, Kamehameha III". Hawaiian Journal of History. 52: 1–25.

doi:

10.1353/hjh.2018.0000.

{{ cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=( help) - ^

a

b Sinclair, Marjorie (1971).

"Sacred Wife of Kamehameha I".

{{ cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=( help) - ^ a b Merry, Sally Engle (2000-01-10). Colonizing Hawai'i: The Cultural Power of Law. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00932-2.

- ^ "Kamehameha III - Hawaii History - Monarchs". web.archive.org. 2017-07-31. Retrieved 2023-03-22.

-

^

"Redirecting..." heinonline.org. Retrieved 2023-03-22.

{{ cite web}}: Cite uses generic title ( help) - ^

a

b

"Redirecting..." heinonline.org. Retrieved 2023-03-22.

{{ cite web}}: Cite uses generic title ( help) - ^ Humanities, National Endowment for the (1893-07-31). "The Hawaiian star. [volume] (Honolulu [Oahu]) 1893-1912, July 31, 1893, Image 2". p. 2. ISSN 2165-915X. Retrieved 2023-03-22.

- ^ a b "Royal Family of Hawaii Official Website". Royal Family Hawaii. Retrieved 2023-03-23.

-

^ IV), Hawaii Sovereigns, etc , 1854-1864 (Kamehameha (1861).

Speeches of His Majesty Kamehameha IV: To the Hawaiian Legislature ... Printed at the Government Press.

{{ cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list ( link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list ( link) - ^ a b c "Kamehameha IV | king of Hawaii | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-03-28.

- ^ a b c d e Adler, Jacob (1968). "King Kamehameha IV's Attitude towards the United States". The Journal of Pacific History. 3: 107–115. ISSN 0022-3344.

- ^ Dyke, Jon M. Van (2007-12-31), "5. The Government Lands", 5. The Government Lands, University of Hawaii Press, pp. 54–58, doi: 10.1515/9780824865603-007/html, ISBN 978-0-8248-6560-3, retrieved 2023-03-28

- ^ "Wayback Machine". web.archive.org. Retrieved 2023-03-28.

-

^ Morris, Alfred D. (1994).

"Death of the Prince of Hawai'i: A Retrospective Diagnosis".

{{ cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=( help) - ^ Humanities, National Endowment for the (1863-12-03). "The Pacific commercial advertiser. [volume] (Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands) 1856-1888, December 03, 1863, Image 2". ISSN 2332-0656. Retrieved 2023-03-29.