| |

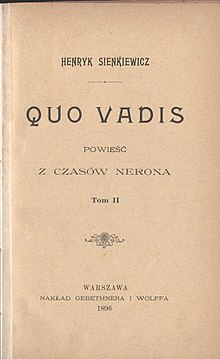

| Author | Henryk Sienkiewicz |

|---|---|

| Original title | Quo vadis. Powieść z czasów Nerona |

| Translator |

Jeremiah Curtin W. S. Kuniczak Samuel Augustus Binion |

| Country | Poland |

| Language | Polish |

| Genre | Historical novel |

| Publisher | Polish dailies (in serial) and Little, Brown (Eng. trans. book form) |

Publication date | 1895–1896 |

| Media type | Print ( Newspaper, Hardback and Paperback) |

Quo Vadis: A Narrative of the Time of Nero is a historical novel written by Henryk Sienkiewicz in Polish. [1]

The novel Quo Vadis tells of a love that develops between a young Christian woman, Lygia (Ligia in Polish), and Marcus Vinicius, a Roman patrician. It takes place in the city of Rome under the rule of emperor Nero, c. AD 64.

Sienkiewicz studied the Roman Empire extensively before writing the novel, with the aim of getting historical details correct. Consequently, several historical figures appear in the book. As a whole, the novel carries a pro-Christian message. [2] [3] [4]

It was first published in installments in the Gazeta Polska between 26 March 1895 and 29 February 1896, [5] [6] as well as in two other journals, Czas and Dziennik Poznański, starting two and three days later. [7] [8] It was published in book form in 1896 and has been translated into more than 50 languages. The novel contributed to Sienkiewicz's Nobel Prize for literature in 1905. [9]

Several movies have been based on Quo Vadis, including two Italian silent films in 1913 and in 1924, a Hollywood production in 1951, a 1985 miniseries directed by Franco Rossi, and a 2001 adaptation by Jerzy Kawalerowicz.

Synopsis

The young Roman patrician Marcus Vinicius falls in love with Lygia, a barbarian hostage being raised in the house of the retired general Aulus Plautius. Vinicius' courtier uncle Petronius uses his influence with the Emperor Nero to have Lygia placed in Vinicius' custody. But first, Nero forces her to appear at a feast on the Palatine Hill. Secretly a Christian after having been converted by Plautius' wife Pomponia Graecina, Lygia is appalled by the degenerate Roman court. She is rescued by her fellow Christians while being escorted to Vinicius' house the following day, and disappears.

Petronius takes pity on the desolate Vinicius, and hires the cunning Greek philosopher Chilo Chilonis to help him find Lygia. [10] Chilo soon establishes that Lygia was Christian, and goes undercover in the Christian community in Rome to find her. When he tells Vinicius that the entire Christian community is going to meet at night outside the city to hear the apostle Peter, Vinicius insists on attending the meeting himself in hope of seeing Lygia there. At the meeting, a disguised Vinicius is strangely touched by Peter's words, but forgets everything when he sees Lygia. He traces Lygia to her hiding place in Transtiber Rome, but is stopped and severely wounded by her barbarian bodyguard Ursus when he goes in to kidnap her.

Instead of killing Vinicius, Lygia and her Christian friends take him in and nurse him back to health. [11] At this point Lygia falls in love with him, and confides in the Apostle Paul. He tells her that she cannot marry a non-Christian, so she leaves Vinicius' bedside and disappears a second time.

After returning to health, Vinicius is a changed man. He starts treating his slaves with more kindness, and rejects the advances of the depraved empress Poppaea Sabina. When Chilo brings him information of Lygia's new hiding place and advises him to surround the house with soldiers, Vinicius has him whipped. Chilo swears revenge while Vinicius goes to Lygia's hiding place alone. After promising Lygia's guardians, the apostles Peter and Paul, to convert, he is engaged to Lygia with their blessing.

The emperor Nero and his court, including Vinicius, go to Antium for recreation. Nero is composing a poem about the burning of Troy, and expresses regret at never having seen a real city burning. Later, the courtiers are shocked when news comes that Rome is aflame. Vinicius rides back to Rome to save Lygia, and Peter baptizes him on the spot after he rescues him and Lygia from the flames.

When Nero returns to Rome and sings his poem about Troy in public, the masses accuse him of igniting the fire. Nero's advisors decide they need a scapegoat. The Prefect of the Praetorian Guard, Tigellinus, suggests the Christians. It is revealed that the idea has been given to him by Chilo, still desperate for revenge on Vinicius after his whipping. Vinicius' uncle Petronius protests, but the empress Poppaea—still nursing a grudge against Vinicus for spurning her advances—overrules him.

Chilo divulges the Christians's hiding place to the authorities, and many of the Christians are arrested, including Lygia. Nero has planned a series of games in the arena, at which the Christians will be butchered in "revenge" for the fire. But even the Roman mob is shocked by the cruelty of the exhibitions: in the penultimate show, Christians are set alight on crosses to illuminate a luxurious feast open to the Roman public. Chilo is so appalled by the scene that he repents and publicly accuses Nero of igniting the fire. As the court scatters, Paul emerges from the shadows and promises Chilo salvation if he truly repents. This gives Chilo the courage to die bravely in the arena the following day, after refusing to retract his accusation.

Meanwhile Lygia and her bodyguard Ursus have been kept for the final show, in which they are exposed to an aurochs in the arena, [12] but when Ursus manages to break the animal's neck, the crowd is impressed and forces Nero to spare the two. She is then married to Vinicius, and the two move away to the latter's mansion in Sicily where they live openly as Christians.

The rest of the novel relates the historical events of Peter's martyrdom ("Quo vadis, Domine?"), Petronius' suicide in the aftermath of the Pisonian conspiracy, and concludes with an account of Nero's ultimate death based on Suetonius.

Characters

- Marcus Vinicius (fictitious son of the historical Marcus Vinicius), a military tribune and Roman patrician who recently returned to Rome. On arrival, he meets and falls in love with Lygia. He seeks the counsel of his uncle Petronius to find a way to possess her. [13]

- Callina (fictitious), usually known as Lygia (Ligia in some translations), the daughter of a deceased king of the Lugii, a barbarian tribe (hence her nickname). Lygia is technically a hostage of the Senate and people of Rome, and was forgotten years ago by her own people. A great beauty, she has converted to Christianity, but her religion is originally unknown to Marcus.

- Gaius Petronius (historical), titled the "arbiter of elegance," former governor of Bithynia. Petronius is a member of Nero's court who uses his wit to flatter and mock him at the same time. He is loved by the Roman mob for his liberal attitudes. Somewhat amoral and a bit lazy, he tries to help his nephew, but his cunning plan is thwarted by Lygia's Christian friends.

- Eunice (fictitious), household slave of Petronius. Eunice is a beautiful young Greek woman who has fallen in love with her master, although he is initially unaware of her devotion.

- Chilon Chilonides (fictitious), a charlatan and a private investigator. He is hired by Marcus to find Lygia. This character is severely reduced in the 1951 film and the 1985 miniseries, but in the novel itself, as well as in the Polish miniseries of 2001, Chilon is a major figure as doublecrossing traitor. His end is clearly inspired by Saint Dismas.

- Nero (historical), Emperor of Rome, portrayed as incompetent, petty, cruel, and subject to manipulation by his courtiers. He listens most intently to flatterers and fools. The novel does indicate, though, that the grossly exaggerating flatteries concerning his abilities as a poet actually have some basis in fact.

- Tigellinus (historical), the prefect of the feared Praetorian Guard. He is a rival of Petronius for Nero's favour, and he incites Nero into committing acts of great cruelty.

- Poppaea Sabina (historical), the wife of Nero. She passionately envies and hates Lygia.

- Acte (historical), an Imperial slave and former mistress of Nero. Nero has grown tired of her and now mostly ignores her, but she still loves him. She studies the Christian faith, but does not consider herself worthy of full conversion. In the 1951 film, it is she who helps Nero commit suicide.

- Aulus Plautius (historical), a respected retired Roman general who commanded the invasion of Britain. Aulus seems unaware (or simply unwilling to know) that Pomponia, his wife, and Lygia, his adoptive daughter, profess the Christian religion.

- Pomponia Graecina (historical), a Christian convert. Dignified and much respected, Pomponia and Aulus are Lygia's adoptive parents, but they are unable to legalize her status. According to Roman law Lygia is still a hostage of the Roman state (i.e., of the Emperor), but she is cared for by the elderly couple.

- Ursus (fictitious), the bodyguard of Lygia. As a fellow tribesman, he served her late mother, and he is strongly devoted to Lygia. As a Christian, Ursus struggles to follow the religion's peaceful teachings, given his great strength and barbarian mindset.

- Peter the Apostle (historical), a weary and aged man with the task of preaching Christ's message. He is amazed by the power of Rome and the vices of Emperor Nero, whom he names the Beast. Sometimes Peter doubts that he will be able to plant and protect the "good seed" of Christianity.

- Paul of Tarsus (historical) takes a personal interest in converting Marcus.

- Crispus (fictitious), a Christian zealot who verges on fanaticism.

- Galba (historical), a Roman Emperor after Nero.

- Epaphroditus (historical), a courtier who helps Nero commit suicide.

Origin of the term

"Quo vadis, Domine?" is Latin for "Where are you going, Lord?" and appears in Chapter 69 of the novel [14] in a retelling of a story from the apocryphal Acts of Peter, in which Peter flees Rome but on his way meets Jesus and asks him why he is going to Rome. Jesus says, "If thou desertest my people, I am going to Rome to be crucified a second time", which shames Peter into going back to Rome to accept martyrdom.

Historical events

Sienkiewicz alludes to several historical events and merges them in his novel, but some of them are of doubtful authenticity.

- In AD 57, Pomponia was indeed charged with practising a "foreign superstition", [15] usually understood to mean conversion to Christianity.[ citation needed] Nevertheless, the religion itself is not clearly identified. According to ancient Roman tradition she was tried in a family court by her own husband Aulus (the pater familias), to be subsequently acquitted. However, inscriptions in the catacombs of Saint Callistus in Rome suggest that members of Graecina's family were indeed Christians.[ citation needed]

- The rumor that Vespasian fell asleep during a song sung by Nero is recorded by Suetonius in the Lives of the Twelve Caesars. [16]

- The death of Claudia Augusta, sole child of Nero, in AD 63. [17]

- The Great Fire of Rome in AD 64, which in the novel is started by orders of Nero. There is no hard evidence to support this, and fires were very common in Rome at the time. In Chapter 50, senior Jewish community leaders advise Nero to blame the fires on Christians; there is no historical record of this either. [18] The fire opens space in the city for Nero's palatial complex, a massive villa with lush artificial landscapes and a 30 meter-tall sculpture of the emperor, as well as an ambitious urban planning program involving the creation of buildings decorated with ornate porticos and the widening of the streets (the urban renewal was carried out only after Nero's death).[ citation needed]

- The suicide of Petronius clearly is based on the account of Tacitus.[ citation needed]

Similarities with Barrett play

Playwright-actor-manager Wilson Barrett produced his successful play The Sign of the Cross in the same year as publication of Quo Vadis? started. The play was first performed 28 March 1895. [19] Several elements in the play strongly resemble those in Quo Vadis. In both, a Roman soldier named Marcus falls in love with a Christian woman and wishes to "possess" her. (In the novel, her name is Lycia, in the play she is Mercia.) Nero, Tigellinus and Poppea are major characters in both the play and novel, and in both, Poppea lusts after Marcus. Petronius, however, does not appear in The Sign of the Cross, and the ending of the play diverges from that of Quo Vadis.

Adaptations

Theatre

Stanislaus Stange adapted the novel into a stage play of the same name which premiered in Chicago at McVicker's Theater's on 13 December 1899. [20] It was later produced the following year on Broadway by F. C. Whitney in a production using music by composer Julian Edwards. [21] The play was also staged at the West End's Adelphi Theatre in 1900. [20]

Jeannette Leonard Gilder also adapted the novel into a stage play of the same name which was also staged on Broadway in the year 1900 at the Herald Square Theatre. [22]

Cinema

Film versions of the novel were produced in

- 1901

- 1910 "Au temps des premiers chrétiens" by André Calmettes

- 1913

- 1924 [23]

- 1951 version directed by Mervyn LeRoy was nominated for eight Academy Awards.

Television

The novel was also the basis for a 1985 mini-series starring Klaus Maria Brandauer as Nero and a 2001 Polish mini-series directed by Jerzy Kawalerowicz.

Others

It was satirized as the quintessential school play gone horribly awry in Shivering Shakespeare, a 1930 Little Rascals short by Hal Roach.

Jean Nouguès composed an opera based on the novel to a libretto by Henri Caïn; it was premiered in 1909. [24] Feliks Nowowiejski composed an oratorio based on the novel, performed for the first time in 1907, and then his most popular work.

Ursus series (1960–1964)

Following Buddy Baer's portrayal of Ursus in the classic 1951 film Quo Vadis, Ursus was used as a superhuman Roman-era character who became the protagonist in a series of Italian adventure films made in the early 1960s.

When the Hercules film craze hit in 1959, Italian filmmakers were looking for other muscleman characters similar to Hercules whom they could exploit, resulting in the nine-film Ursus series listed below. Ursus was referred to as a "Son of Hercules" in two of the films when they were dubbed in English (in an attempt to cash in on the then-popular Hercules craze), although in the original Italian films, Ursus had no connection to Hercules whatsoever. In the English-dubbed version of one Ursus film (retitled Hercules, Prisoner of Evil), Ursus was referred to throughout the entire film as Hercules.

There were a total of nine Italian films that featured Ursus as the main character, listed below as follows: Italian title/ English translation of the Italian title (American release title);

- Ursus / Ursus ( Ursus, Son of Hercules, 1960) a.k.a. Mighty Ursus, a.k.a. Le fureur d'Hercule, starring Ed Fury

- La Vendetta di Ursus / The Revenge of Ursus ( The Vengeance of Ursus, 1961), starring Samson Burke

- Ursus e la Ragazza Tartara / Ursus and the Tartar Girl (Ursus and the Tartar Princess, 1961) a.k.a. The Tartar Invasion, a.k.a. The Tartar Girl; starring Joe Robinson, Akim Tamiroff, Yoko Tani, directed by Remigio Del Grosso

- Ursus Nella Valle dei Leoni / Ursus in the Valley of the Lions ( Valley of the Lions, 1962) starring Ed Fury, this film revealed the origin story of Ursus

- Ursus il gladiatore ribelle / Ursus the Rebel Gladiator ( The Rebel Gladiators, 1962), starring Dan Vadis

- Ursus Nella Terra di Fuoco / Ursus in the Land of Fire ( Son of Hercules in the Land of Fire, 1963) a.k.a. Son of Atlas in the Land of Fire, starring Ed Fury

- Ursus il terrore dei Kirghisi / Ursus, the Terror of the Kirghiz ( Hercules, Prisoner of Evil, 1964) starring Reg Park

- Ercole, Sansone, Maciste e Ursus: gli invincibili / Hercules, Samson, Maciste and Ursus: The Invincibles ( Samson and His Mighty Challenge, 1964), starring Yan Larvor as Ursus (a.k.a. "Combate dei Gigantes" or "Le Grand Defi")

- Gli Invincibili Tre / The Invincible Three ( 3 Avengers, 1964), starring Alan Steel as Ursus

Recognition

In the small church of "Domine Quo Vadis", there is a bronze bust of Henryk Sienkiewicz. It is said[ according to whom?] that Sienkiewicz was inspired to write his novel Quo Vadis while sitting in this church.[ citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ Halsey, F. R. (5 February 1898). "Historians of Nero's Time" (PDF). New York Times. p. BR95. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ^ "The Man Behind Quo Vadis". Culture.pl. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- ^ Socken, Paul (1 September 2013). The Edge of the Precipice: Why Read Literature in the Digital Age?. McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP. ISBN 9780773589872.

- ^ Soren, David (2010). Art, Popular Culture, and The Classical Ideal in the 1930s: Two Classic Films – A Study of Roman Scandals and Christopher Strong. Midnight Marquee & BearManor Media.

- ^ "Gazeta Polska 26 March 1895" (in Polish). Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- ^ David J. Welsh, " Serialization and structure in the novels of Henryk Sienkiewicz" in: The Polish Review Vol. 9, No. 3 (1964) 53.

- ^ "Czas 28 March 1895" (in Polish). Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- ^ "Dziennik Poznański 29 March 1895" (in Polish). Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- ^ "International Conference, "Quo vadis": inspirations, contexts, reception. Henryk Sienkiewicz and his vision of Ancient Rome | Miejsce "Quo vadis?" w kulturze włoskiej. Przekłady, adaptacje, kultura popularna". www.quovadisitaly.uni.wroc.pl. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- ^ "Chilon Chilonides - charakterystyka – Quo vadis - opracowanie – Zinterpretuj.pl" (in Polish). 2 August 2022. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ^ "Marek Winicjusz - charakterystyka – Quo vadis - opracowanie – Zinterpretuj.pl" (in Polish). 30 July 2022. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ^ "Ligia (Quo vadis) - charakterystyka – Quo vadis - opracowanie – Zinterpretuj.pl" (in Polish). 30 July 2022. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ^ "Marek Winicjusz - charakterystyka - Quo vadis - Henryk Sienkiewicz". poezja.org (in Polish). Retrieved 24 November 2022.

-

^

Sienkiewicz, Henryk (June 1896).

"Quo Vadis: A Narrative of the Time of Nero". Translated from the Polish by

Jeremiah Curtin.

Quo vadis, Domine?

- ^ Tacitus. "XIII.32". Annals.

- ^ Suetonius. "Divus Vespasian". The Twelve Caesars. 4.

- ^ "Neron (Quo vadis) - charakterystyka - Henryk Sienkiewicz". poezja.org (in Polish). Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- ^ "Quo vadis - streszczenie - Henryk Sienkiewicz". poezja.org (in Polish). Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- ^ Wilson Barrett's New Play, Kansas City Daily Journal, (Friday, 29 March 1895), p. 2.

- ^ a b J. P. Wearing (2013). "Quo Vadis?". The London Stage 1900-1909: A Calendar of Productions, Performers, and Personnel. Scarecrow Press. p. 15. ISBN 9780810892941.

- ^ Thomas Allston Brown (1903). "Quo Vadis". A History of the New York Stage from the First Performance in 1732 to 1901, Volume 3. Dodd, Mead. p. 611.

- ^ "DRAMATIC AND MUSICAL; Two Melodramatic Plays Founded on "Quo Vadis."". The New York Times. 10 April 1900. p. 7.

- ^ Monica Silveira Cyrino (2005). Big Screen Rome. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-4051-5032-3.

- ^ Gesine Manuwald, Nero in Opera: Librettos as Transformations of Ancient Sources. (Tranformationen der Antike; 24). Berlin: De Gruyter, 2013. ISBN 9783110317138

External links

- Quo Vadis at Standard Ebooks

- Quo Vadis at Project Gutenberg, translated by Jeremiah Curtin (plain text and HTML)

Quo Vadis public domain audiobook at

LibriVox

Quo Vadis public domain audiobook at

LibriVox- Quo Vadis at Internet Archive and Google Books (various translations, scanned books original editions illustrated)

- Quo Vadis, in Polish.

- Quo Vadis, in Armenian.

- Two Thousand Versions of Quo Vadis and Counting

- Polish novels

- 1895 Polish novels

- Polish novels adapted into films

- Novels by Henryk Sienkiewicz

- Novels first published in serial form

- Novels set in ancient Rome

- Novels about Catholicism

- Books about Nero

- Cultural depictions of Poppaea Sabina

- Works originally published in Polish newspapers

- Christian novels

- Polish historical novels

- Polish novels adapted into plays

- Novels adapted into operas

- Polish novels adapted into television shows

- Works based on the Annals (Tacitus)

- Novels set in the 1st century