This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's

quality standards. (January 2024) |

SpaceX has stated its ambition to facilitate the colonization of Mars via the development of the Starship launch vehicle. The company states that this is necessary for the long-term survival of the human species. [1]

Elon Musk, who founded SpaceX, first presented his goal of enabling Mars colonization in 2001 as a member of the Mars Society's board of directors. In the 2000s and early 2010s, SpaceX made many vehicle concepts for delivering payloads and crews to Mars, including space tugs, heavy-lift launch vehicles, and Red Dragon capsules. The company's current Mars plan was first formally proposed at the 2016 International Astronautical Congress alongside a fully-reusable launch vehicle, the Interplanetary Transport System. Since then, the launch vehicle proposal was altered and renamed to "Starship", and has been in development since. On its third test flight, it reached its desired trajectory for the first time on March 14, 2024. The company has given many estimates of dates of the first human landing on Mars; the most recent discussion of which occurred during a company all hands meeting in April 2024. [2]

SpaceX's early missions to Mars will involve small fleets of Starship spacecraft, funded by public–private partnerships. [3]The company hopes that once infrastructure is established on Mars and the launch cost is reduced further, colonization can begin. The Mars program has been criticized by some as far-fetched, partially because of uncertainties regarding its financing [4] and because it primarily addresses transportation to Mars and not the steps that follow. George Dvorsky writing for Gizmodo characterized Musk's timeline for Martian colonization as "stupendously unreasonable". [5] For reference, Musk's timeline for the colonization of Mars involves a crewed mission as early as 2029 and sustainability by 2050. [6]

Some experts, like Robert Zubrin, support the concept due to the prevalence of water ice in the form of permafrost on Mars, as well as other resources like carbon dioxide and nitrogen; [7] some are opposed to the concept, believing the planet's lack of both breathable air and protective magnetosphere to be unacceptable problems. [8] A common sentiment among those opposed to Mars colonization is that humans should focus on solving problems on Earth before moving on to extraplanetary colonization. [9]

Prior Mission Concepts

Mars Colonial Transporter

Red Dragon capsule

Red Dragon

Red Dragon was a 2011-2017 concept mission which would have used a modified Dragon 2 spacecraft as a low-cost Mars lander. If flown, it would have been launched on a Falcon Heavy, and land solely via the use of its SuperDraco retro-propulsion thrusters, [18] as parachutes would have required significant vehicle modifications. [19]

In 2011, SpaceX planned on proposing Red Dragon for the Discovery Mission #13, which would launch in 2022, [20] [21] [22] but it was not submitted. It was then proposed in 2014 as a low-cost way for NASA to achieve a Mars sample return by 2021. In the concept, the Red Dragon capsule would be equipped with the system needed to return samples gathered on Mars. NASA did not fund this concept.

In 2016, SpaceX planned on launching two Red Dragon vehicles [23] in 2018, [24] [25] with NASA providing technical support instead of funding. [26] However, in 2017, Red Dragon was cancelled, in favor of the much larger Starship spacecraft. [27]

Program manifest

SpaceX has stated on several occasions aspirational plans to build a crewed base on Mars for an extended surface presence, which it hopes will grow into a self-sufficient colony. [28] [29] A successful colonization, meaning an established human presence on Mars growing over many decades, would ultimately involve many more economic actors than SpaceX. [30] [31] [32]

Before any people are transported to Mars, a number of cargo missions would be undertaken first in order to transport the requisite equipment, habitats and supplies. [33] Equipment that would accompany the early groups would include "machines to produce fertilizer, methane and oxygen from Mars' atmospheric nitrogen and carbon dioxide and the planet's subsurface water ice" as well as construction materials to build transparent domes for crop growth. [34] [35]

Musk has made statements on several occasions about aspirational dates for Starship's earliest possible Mars landing, [36] including in 2022, that a mission to Mars could be no earlier than 2029. [37]

Exploration

Musk plans for the first crewed Mars missions to have approximately 12 people, with goals to "build out and troubleshoot the propellant plant and Mars Base Alpha power system" and establish a "rudimentary base." The company plans to process resources on Mars into fuel for return journeys, [38] and use similar technologies on Earth to create carbon-neutral propellant. [39]

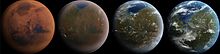

Colonization and terraforming

The program aims to send a million people to Mars, using a thousand Starships sent during a Mars launch window. [40] Proposed journeys would require 80 to 150 days of transit time, [32] averaging approximately 115 days (for the nine synodic periods occurring between 2020 and 2037). [41] This plan has been described as 'pure delusion' by George Dvorsky, writing for Gizmodo, [5] and as a 'dangerous delusion' by Lord Martin Rees, a British cosmologist/astrophysicist and the Astronomer Royal of the United Kingdom. [42] Serkan Saydam, a mining engineering professor from the University of New South Wales said that we will likely still lack the technology needed to create and maintain a martian colony of a million people by 2050. [5]

Tenets

As early as 2007, Elon Musk stated a personal goal of eventually enabling human exploration and settlement of Mars, [43] although his personal public interest in Mars goes back at least to 2001 at the Mars Society. [44]: 30–31 SpaceX has stated its goal is to colonize Mars to ensure the long-term survival of the human species. [4]

Launch vehicle

Starship is designed to be a fully reusable and orbital rocket, aiming to drastically reduce launch costs and maintenance between flights. [45]: 2 The rocket consists of a Super Heavy first stage booster and a Starship second stage spacecraft, [46] powered by Raptor and Raptor Vacuum engines. [47] Both stages are made from stainless steel. [48]

Methane was chosen for the Raptor engines because it is relatively cheap, produces low amount of soot as compared to other hydrocarbons, [49] and can be created on Mars from carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and hydrogen via the Sabatier reaction. [50] The engine family uses a new alloy for the main combustion chamber, allowing it to contain 300 bar (4,400 psi) of pressure, the highest of all current engines. [49] In the future, it may be mass-produced [49] and cost about $230,000 per engine or $100 per kilonewton. [51]

Starship's reusability is expected to reduce launch costs, expanding space access to more payloads and entities. [52] According to Robert Zubrin, aerospace engineer and advocate for human exploration of Mars, Starship's planned lower launch cost could make space-based economy, colonization, and mining practical. [44]: 25, 26 According to Robert Zubrin, lower cost to space may potentially make space research profitable, allowing major advancements in medicine, computers, material science, and more. [44]: 47, 48 Musk has stated that a Starship orbital launch could eventually cost $2 million, starting at $10 million within 2-3 years and dropping with time. [53] Pierre Lionnet, director of research at Eurospace, claimed otherwise, citing the rocket's multi-billion-dollar development cost and its current lack of external demand. [54]

Reception and feasibility

As of December 2023, SpaceX has not publicly detailed plans for the spacecraft's life-support systems, radiation protection, and in situ resource utilization, which are essential for space colonization. [55]

Notes

References

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (April 23, 2021). "Elon Musk wants SpaceX to reach Mars so humanity is not a 'single-planet species'". CNBC. Archived from the original on October 2, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ^ "At Starbase, Elon Musk provided an update on the company's plans to send humanity to Mars, the best destination to begin making life multiplanetary".

- ^ "SpaceX Mars Plans for 1,000 Spaceships to Deliver First Colonists Within 7 to 9 Years". International Business Times UK. April 16, 2024. Retrieved April 16, 2024.

- ^ a b Chang, Kenneth (September 27, 2016). "Elon Musk's Plan: Get Humans to Mars, and Beyond". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 29, 2016. Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Elon Musk's Plan to Send a Million Colonists to Mars by 2050 Is Pure Delusion". Gizmodo. June 3, 2022. Archived from the original on December 23, 2023. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ Torchinsky, Rina (March 17, 2022). "Elon Musk hints at a crewed mission to Mars in 2029". NPR. Archived from the original on June 8, 2022. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ Zubrin, Robert (January 2024). "The Case for Colonizing Mars, by Robert Zubrin". NSS. Archived from the original on January 26, 2024. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ Wattles, Jackie (September 8, 2020). "Colonizing Mars could be dangerous and ridiculously expensive. Elon Musk wants to do it anyway | CNN Business". CNN. Archived from the original on January 26, 2024. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ^ Dorminey, Bruce. "Why We Should Save Earth Before Colonizing Mars". Forbes. Archived from the original on February 14, 2024. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ^ a b c Rosenberg, Zach (October 15, 2012). "SpaceX aims big with massive new rocket". Flight Global. Archived from the original on July 3, 2015. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

- ^ Coppinger, Rob (November 23, 2012). "Huge Mars Colony Eyed by SpaceX Founder Elon Musk". Space.com. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (December 29, 2015). "Speculation mounts over Elon Musk's plan for SpaceX's Mars Colonial Transporter". GeekWire. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ^ Schaefer, Steve. "SpaceX IPO Cleared For Launch? Elon Musk Says Hold Your Horses". Forbes. Archived from the original on November 28, 2023. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^ a b Belluscio, Alejandro G. (March 7, 2014). "SpaceX advances drive for Mars rocket via Raptor power". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on September 11, 2015. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

- ^ Heath, Chris (December 12, 2015). "How Elon Musk Plans on Reinventing the World (and Mars)". GQ. Archived from the original on December 12, 2015. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

- ^ Nellis, Stephen (February 19, 2014). "SpaceX's propulsion chief elevates crowd in Santa Barbara". Pacific Coast Business Times. Archived from the original on September 26, 2016. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (March 7, 2014). "SpaceX advances drive for Mars rocket via Raptor power". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^ David, Leonard (March 7, 2014). "Project 'Red Dragon': Mars Sample-Return Mission Could Launch in 2022 with SpaceX Capsule". Space.com. Archived from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ^ "Red Dragon", Feasibility of a Dragon-derived Mars lander for scientific and human-precursor investigations (PDF), 8m.net, October 31, 2011, archived (PDF) from the original on June 16, 2012, retrieved May 14, 2012

- ^ Spacex Dragon lander could land on Mars with a mission under the NASA Discovery Program cost cap. Archived 2016-11-10 at the Wayback Machine 20 June 2014.

- ^ Wall, Mike (July 31, 2011). "'Red Dragon' Mission Mulled as Cheap Search for Mars Life". SPACE.com. Archived from the original on December 1, 2011. Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- ^ "NASA ADVISORY COUNCIL (NAC) - Science Committee Report" (PDF). Ames Research Center, NASA. November 1, 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 20, 2013. Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- ^ Agamoni Ghosh (May 11, 2017). "Nasa says SpaceX may send two Red Dragon spacecraft to Mars in 2020 in case one fails". International Business Times. Archived from the original on May 18, 2017. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ Davenport, Christian (June 13, 2016). "Elon Musk provides new details on his 'mind blowing' mission to Mars". Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 10, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ^ Drake, Nadia (April 27, 2016). "SpaceX Plans to Send Spacecraft to Mars in 2018". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on September 19, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2016.

- ^ Newmann, Dava. "Exploring Together". NASA Official Blog. Archived from the original on May 1, 2016. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

- ^ Ralph, Eric (July 19, 2017). "SpaceX skipping Red Dragon for "vastly bigger ships" on Mars, Musk confirms". TESLARATI. Archived from the original on May 26, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ "SpaceX wants to use the first Mars-bound BFR spaceships as Martian habitats" Archived November 9, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Eric Ralph, TeslaRati. August 27, 2018.

- ^ "We're going to Mars by 2024 if Elon Musk has anything to say about it" Archived February 3, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Elizabeth Rayne, SyFy Wire. August 15, 2018.

- ^ Berger, Eric (September 28, 2016). "Musk's Mars moment: Audacity, madness, brilliance—or maybe all three". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on October 13, 2016. Retrieved October 13, 2016.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (October 10, 2016). "Can Elon Musk get to Mars?". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on October 13, 2016. Retrieved October 12, 2016.

- ^ a b Boyle, Alan (September 27, 2016). "SpaceX's Elon Musk makes the big pitch for his decades-long plan to colonize Mars". GeekWire. Archived from the original on October 3, 2016. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

-

^

Gwynne Shotwell (March 21, 2014).

Broadcast 2212: Special Edition, interview with Gwynne Shotwell (audio file). The Space Show. Event occurs at 29:45–30:40. 2212. Archived from

the original (mp3) on March 22, 2014. Retrieved March 22, 2014.

would have to throw a bunch of stuff before you start putting people there. ... It is a transportation system between Earth and Mars.

- ^ "Huge Mars Colony Eyed by SpaceX Founder". Discovery News. December 13, 2012. Retrieved March 14, 2014.

- ^ Carroll, Rory (July 17, 2013). "Elon Musk's mission to Mars". TheGuardian. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (September 28, 2019). "Elon Musk Sets Out SpaceX Starship's Ambitious Launch Timeline". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- ^ Torchinsky, Rina (March 17, 2022). "Elon Musk hints at a crewed mission to Mars in 2029". NPR. Archived from the original on June 8, 2022. Retrieved June 16, 2022.

- ^ Sommerlad, Joe (May 28, 2021). "Elon Musk reveals Starship progress ahead of first orbital flight of Mars-bound craft". The Independent. Archived from the original on August 23, 2021. Retrieved December 4, 2021.

- ^ Killelea, Eric (December 16, 2021). "Musk looks to Earth's atmosphere as source of rocket fuel". San Antonio Express-News. Archived from the original on December 20, 2021. Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- ^ Kooser, Amanda (January 16, 2020). "Elon Musk breaks down the Starship numbers for a million-person SpaceX Mars colony". CNET. Archived from the original on February 7, 2022. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ "Making Humans a Multiplanetary Species" (PDF). SpaceX. September 27, 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2016. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ "Elon Musk's plans for life on Mars are a 'dangerous delusion', says British chief astronomer". Sky News. Archived from the original on January 11, 2024. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ Hoffman, Carl (May 22, 2007). "Elon Musk Is Betting His Fortune on a Mission Beyond Earth's Orbit". Wired Magazine. Archived from the original on November 14, 2012. Retrieved March 14, 2014.

- ^ a b c Zubrin, Robert (May 14, 2019). The Case for Space: How the Revolution in Spaceflight Opens Up a Future of Limitless Possibility. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-63388-534-9. OCLC 1053572666.

- ^ Inman, Jennifer Ann; Horvath, Thomas J.; Scott, Carey Fulton (August 24, 2021). SCIFLI Starship Reentry Observation (SSRO) ACO (SpaceX Starship). Game Changing Development Annual Program Review 2021. NASA. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (August 6, 2021). "Biggest ever rocket is assembled briefly in Texas". BBC News. Archived from the original on August 11, 2021. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Ryan, Jackson (October 21, 2021). "SpaceX Starship Raptor vacuum engine fired for the first time". CNET. Archived from the original on June 9, 2022. Retrieved June 9, 2022.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (September 28, 2019). "Elon Musk Sets Out SpaceX Starship's Ambitious Launch Timeline". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- ^ a b c O'Callaghan, Jonathan (July 31, 2019). "The wild physics of Elon Musk's methane-guzzling super-rocket". Wired UK. Archived from the original on February 22, 2021. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ^ Sommerlad, Joe (May 28, 2021). "Elon Musk reveals Starship progress ahead of first orbital flight of Mars-bound craft". The Independent. Archived from the original on August 23, 2021. Retrieved December 4, 2021.

- ^ Sesnic, Trevor (August 11, 2021). "Starbase Tour and Interview with Elon Musk". The Everyday Astronaut (Interview). Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ Mann, Adam (May 20, 2020). "SpaceX now dominates rocket flight, bringing big benefits—and risks—to NASA". Science. doi: 10.1126/science.abc9093. S2CID 219490398. Archived from the original on November 7, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- ^ Duffy, Kate. "Elon Musk says he's 'highly confident' that SpaceX's Starship rocket launches will cost less than $10 million within 2-3 years". Business Insider. Archived from the original on January 19, 2024. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ^ Bender, Maddie (September 16, 2021). "SpaceX's Starship Could Rocket-Boost Research in Space". Scientific American. Archived from the original on October 26, 2021. Retrieved November 22, 2021.

- ^ Grush, Loren (October 4, 2019). "Elon Musk's future Starship updates could use more details on human health and survival". The Verge. Archived from the original on October 8, 2019. Retrieved January 24, 2022.