| |

Screenshot  A Parler feed showing

Andy Biggs | |

| Type of business | Private |

|---|---|

Type of site | Social networking service |

| Founded | 2018 [1] |

| Founder(s) | John Matze Jr. Jared Thomson Rebekah Mercer [1] |

| CEO | Ryan Rhodes |

| Key people | Elise Pierotti, Jaco Booyens |

| Industry | Internet |

| Employees | 30 (as of 2020) [2] |

| URL |

parler |

| Registration | Required |

| Users | 700,000 to 1 million (active) as of January 2022 [update] [3] 20 million (total) as of January 2021 [update] [4] |

| Launched | September 2018 [5] |

| Current status | Online |

Parler (pronounced "parlor") is a now-closed [6] American alt-tech social networking service associated with conservatives. [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12][ excessive citations] Launched in August 2018, Parler marketed itself as a free speech-focused and unbiased alternative to mainstream social networks such as Twitter and Facebook. [13] [14] [15] Journalists described Parler as an alt-tech alternative to Twitter, with its users including those banned from mainstream social networks or who oppose their moderation policies. [16] [14] [17] [18][ excessive citations]

Parler received criticism for its content policies, which some journalists and users claimed were more restrictive than the company portrays and sometimes more restrictive than those of its competitors. [19] [20] [21] [22][ excessive citations] Conservatives praised Parler as offering an alternative to censorship they claim to endure on more mainstream platforms, such as Facebook and Twitter. [23]

Parler's userbase grew exponentially during 2020 with minimal content moderation. [24] [25] After reports that Parler was used to coordinate the 2021 storming of the U.S. Capitol, several companies denied it their services. [26] Apple and Google removed Parler's mobile app from their app stores, and Parler went offline on January 10, 2021, when Amazon Web Services canceled its hosting services. [27] [28] [29] Before it went offline in January 2021, according to Parler, the service had about 15 million users. [30] Parler called the removals "a coordinated attack by the tech giants to kill competition in the marketplace". [24] Parler resumed service on February 15, 2021, after moving domain registration to Epik. [31] A version of the app with added content filters was released on the Apple App Store on May 17, 2021. [32] [33] [34] Parler returned to Google Play on September 2, 2022. [35]

Parler was acquired by the digital media conglomerate Starboard on April 14, 2023, and was shut down on the same day. [36] According to a statement by Starboard on the website's holding page, now removed, this was a temporary measure to allow the site to "undergo a strategic assessment". [37] [38]

On December 15, 2023, the company was sold to a new co-owner group consisting of Ryan Rhodes, Elise Pierotti and Jaco Booyens. Ryan Rhodes was appointed CEO. [39] A 2024 relaunch was hinted at by the new ownership soon after the company purchase. In January 2024, the company's external social media outlets officially restarted operations to announce the relaunch. The platform itself remains inaccessible, but the website has been restored.

History

Parler was founded by John Matze Jr. and Jared Thomson in Henderson, Nevada, in August 2018. The company's name was taken from the French word "parler", meaning "to speak". [1] [40] [17] The name was originally intended to be pronounced as in French (French pronunciation: [paʁ.le] ⓘ, English approximation: PAR-lay), but is now pronounced as the English word " parlor" ( /pɑːrlər/ PAR-ler). [41] [42] The Wall Street Journal first reported in November 2020 that conservative investor Rebekah Mercer had funded Parler, and Mercer has since been revealed to have been a co-founder of the company. [2] [1] [40] [43] According to Mercer, she co-founded Parler to counter the "ever-increasing tyranny and hubris of our tech overlords". [44] Thomson serves as the chief technology officer, and Matze was Parler's chief executive officer from its founding until January 2021. [45] [5] Both are alumni of the University of Denver computer science program, and were roommates while in college. [17] [43] Some other Parler senior staff also attended the school. [17]

2018–2019

Parler launched in August 2018, billing itself as an unbiased and free speech alternative to larger social media platforms, such as Twitter and Facebook. [41] [46] [47] The service was relatively unknown until a December 2018 tweet by conservative commentator and activist Candace Owens brought 40,000 new users to Parler, causing Parler's servers to malfunction. [46] [48] The service initially attracted some Republican personalities, including then-Trump campaign manager Brad Parscale, Utah Senator Mike Lee, and Trump attorney Rudy Giuliani, as well as some who had been banned from other social media networks, such as right-leaning activists and commentators Gavin McInnes, Laura Loomer, and Milo Yiannopoulos. [16] [41] Reuters wrote that Parler had "mostly been a home for supporters of U.S. President Donald Trump" until June 2019. Matze told the news organization that although he had originally intended Parler to be bipartisan, he had focused its marketing efforts toward conservatives as they began to join the service. [16]

In May 2019, Parler had 100,000 users. [41] [46] In June 2019, Parler said its user base more than doubled after around 200,000 accounts from Saudi Arabia signed up to the network. Largely supporters of Saudi Arabian Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the users migrated from Twitter after alleging they were experiencing censorship on the platform. Although Twitter did not acknowledge removing posts by Saudi users that might have triggered the exodus, the company had previously deactivated hundreds of accounts that had been supportive of the Saudi government, which Twitter had described as "inauthentic" accounts in an " electronic army" pushing the Saudi government's agenda. [16] [49] The influx of new accounts to Parler caused some service interruptions, making the site at times unusable. [49] Parler described the Saudi accounts as part of "the nationalist movement of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia", and encouraged other users to welcome them to the service. [16] Some of the Saudi users tweeted the ' #MAGA' hashtag and photos of President Trump with the Saudi royal family in order to curry favor with the Trump-supporting and far-right users on the service. [49] The Saudi accounts found a mixed reception among the existing user base; though some welcomed the Saudi users, others made Islamophobic remarks, and some expressed beliefs that the new accounts were bots. [16]

2020

Parler experienced a surge in signups in mid-2020. [51] In May, Twitter sparked outrage among President Trump and his supporters when it flagged some of the president's tweets about mail-in ballots as "potentially misleading", and a tweet regarding the George Floyd protests as "glorifying violence". [21] [52] [53] [54] In response, Parler published a "Declaration of Internet Independence" modeled after the United States Declaration of Independence, and began using the "#Twexit" hashtag (a portmanteau of "Twitter" and " Brexit"). Describing Twitter as a "Tech Tyrant" that censored conservatives, the campaign encouraged Twitter users to migrate to Parler. [55] Conservative commentator Dan Bongino announced on June 16 that he had purchased an "ownership stake" in Parler, in an effort to "fight back against" what he described as "Tech Tyrants" Facebook and Twitter. [50] Parscale, who at the time was managing the Trump campaign, endorsed Parler in a tweet on June 18, also writing, "Hey @twitter your days are numbered", and including a screenshot of a tweet from President Trump which Twitter had flagged as "manipulated media". [51]

On June 19, right-wing English media personality Katie Hopkins was permanently suspended from Twitter for violating their policies on "hateful conduct". [56] [57] An account falsely claiming to be hers appeared on Parler shortly after the ban, and was quickly verified by Parler. After the impersonator account had collected $500 in donations solicited on Parler, purportedly to sue Twitter over the ban, Parler removed it. A Twitter account affiliating itself with the hacktivist group Anonymous claimed responsibility for the imposture on June 20, and said they would donate the money they had collected to Black Lives Matter groups, a movement Hopkins had mocked in the past. Parler's then-CEO Matze made a public apology, with Parler acknowledging that the impersonator had been "verified by an employee improperly". [56] Hopkins herself joined Parler on June 20, with Matze posting that he had personally verified her account. [58] [59] The incident drew some attention to Parler within the United Kingdom. Thirteen Members of Parliament had joined as of June 23, and some British right-wing and conservative activists endorsed the service over Twitter. [56]

On June 24, 2020, The Wall Street Journal reported that the Trump campaign was looking for alternatives to social media networks that had restricted their posts and advertising, and that Parler was being considered. [60] [61] Beginning in mid-2020, Parler negotiated with The Trump Organization, offering a 40% stake in the social network in exchange for Trump making Parler his primary social media platform. As a part of the deal, Trump would have had to post all his content to Parler at least four hours before publishing it to other networks. [43] According to Michael Wolff, Trump representatives also included the condition that Parler ban anyone speaking negatively about Trump, which Parler did not accept. [62] The White House Counsel's office reportedly halted the negotiations on the grounds that such a partnership would violate ethics rules as long as Trump was president. The general counsel for the nonpartisan watchdog non-profit Project On Government Oversight, Scott Amey, said there ought to be an "immediate criminal investigation" into the Trump administration over the negotiations. [43]

Texas Senator Ted Cruz published a YouTube video on June 25, in which he denounced other social media platforms for "flagrantly silencing those with whom they disagree" and announced that he was "proud to join Parler". [63] Other prominent Republican and conservative figures also joined in June, including Ohio Representative Jim Jordan, New York Representative Elise Stefanik, and former U.N. ambassador Nikki Haley. [61]

Jair Bolsonaro, the right-wing President of Brazil, joined Parler on July 13; [64] [65] Four months earlier in March 2020, Twitter had removed some of President Bolsonaro's posts for violating their rules on spreading disinformation related to the COVID-19 pandemic. [65] [66] Earlier in July, his son Flávio Bolsonaro had endorsed Parler on Twitter. As a result, Parler experienced a wave of signups from Brazil in July. [65] According to Bloomberg News on July 15, 2020, Brazilian users made up over half of all Parler signups that month. [51]

On October 1, 2020, Reuters reported that people associated with the Russian Internet Research Agency, a group known for their interference in the 2016 presidential election, had been operating social media accounts on both mainstream and alt-tech platforms. One of the accounts, named Leo, identified in an FBI probe as a "key asset in an alleged Russian disinformation campaign", had been spreading "familiar and completely false" information, including claims that mail-in voting was prone to fraud, that President Trump was infected with coronavirus by leftist activists, and that Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden was a "sexual predator". [67] Axios reported that the account had not found much of an audience on mainstream platforms, but had caught on among the alt-tech platforms; the Twitter account had fewer than 200 followers, but had 14,000 on Parler. [68] Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn all took actions to suspend the accounts from their platforms. [69] The Washington Post reported on October 7 that Parler had declined to terminate the account after being informed of its connections to the disinformation organization, stating they did not need to act because they had not been contacted directly by U.S. law enforcement. [67]

Also in October, as Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube acted to ban content supporting the far-right QAnon conspiracy theory, [70] thousands of QAnon proponents migrated to Parler. [71] [72] Similar actions by Facebook against organizations promoting violence prompted some members of the Proud Boys and adherents of the boogaloo movement to move to Parler. [72]

Parler experienced a wave of signups following the 2020 U.S. presidential election from American conservatives, concerned that their posts – or those of other conservatives on mainstream social networks – would be affected by the platforms' efforts to quash misinformation about the election. [72] [73] [74] The app was downloaded nearly a million times in the week following Election Day on November 3, and rose to the top of both the Apple App Store's and the Google Play Store's lists of most popular free apps. Following the election, The Verge reported that Parler had become a "central hub for many of the conservative protests against recent election results", including the Stop the Steal conspiracy theory, which alleged widespread electoral fraud in the 2020 presidential election. [75] [76] The surge had largely abated by December 2020, with downloads of the app returning to numbers similar to before the election. [77] [78] According to findings from Stanford researchers published on January 28, 2021, Parler registered 7,029 new users per minute during the election. [79]

A verified account on Parler claiming to be Ron Watkins, the former site administrator of 8chan and son of 8chan owner Jim Watkins, made several posts on November 15, 2020, appearing to confirm theories that his father was Q, the anonymous figure behind the QAnon conspiracy theory. [80] It was later determined that security researcher Aubrey Cottle had taken advantage of Parler security flaws to change the name of an already-verified Parler account, giving it the appearance of belonging to and having been verified as Watkins. [23] This incident led to a feud between Watkins and Parler investor Dan Bongino, with Watkins publicly criticizing Parler's security on Twitter and describing the service as "compromised". Bongino responded by tweeting insults at Watkins. [81] [82]

2021

Parler was among the social media services used to plan the storming of the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021. [83] [84] [85] [86] [ excessive citations]On January 2, Parler notified the FBI about material that Parler's lawyers found sufficiently alarming to warrant law enforcement attention, including posts by a user who declared that January 6 would be "the final stand where we are drawing the red line at Capitol Hill". [87] On January 5, the Secret Service warned the Capitol Police about an individual who intended to attend the rally and incite violence, and whose Parler posts included threats of violence against police. [88] Mentions of "civil war" on Parler increased fourfold in the hours just prior to the storming. [89] According to BuzzFeed News, after the riot at the Capitol, Parler had been "overrun" with death threats, encouragement of violence, and calls for Trump supporters to join another armed march on Washington, D.C. on the day before the inauguration of Joe Biden. [29] Activists, including Sleeping Giants, and employees of technology companies that had been providing services to Parler began to pressure those companies, which included Google, Apple, and Amazon, to deny service to Parler. [30]

Parler experienced a wave of downloads after Twitter permanently suspended President Donald Trump from their platform due to his remarks about the storming of the Capitol. This led Parler to become the top downloaded app on the Apple App Store on January 8. [90]

Shutdown by service providers

|

January 6 United States Capitol attack |

|---|

|

| Timeline • Planning |

| Background |

| Participants |

| Aftermath |

On January 8, two days after the storming of the Capitol, Google announced that it was pulling Parler from the Google Play Store, contending that its lack of "moderation policies and enforcement" posed a "public safety threat". [91] [92] Also on January 8, Apple informed Parler that they had received complaints about its role in the coordination of the riot in Washington D.C., the existence of "objectionable content" on the service, and that they had observed that "the app also appears to continue to be used to plan and facilitate yet further illegal and dangerous activities," in violation of Parler's own guidelines forbidding such content. Apple requested Parler submit a "moderation improvement plan" within 24 hours or face removal from the App Store. On Parler, Matze posted that Parler would not "cave to pressure", and accused Apple of being anti-competitive. [93] Apple followed through with their warning the next day, removing Parler from the App Store on January 9. [94] Ahead of the shutdown, some Parler users issued calls for violence and armed protests at state capitols and circulated conspiracy theories about Apple. [95] Apple CEO Tim Cook later explained that in the company's view, "free speech and incitement of violence" do not have "an intersection". [96] Cloud communications company Twilio ended service to Parler, which made the service's two-factor authentication system stop working; Okta also denied them access to their identity management service, resulting in Parler losing access to some of their software tools. [30] In addition, the database company ScyllaDB terminated its relationship with Parler, who had been using Scylla's Enterprise database. [97]

On January 9, Amazon announced that it would suspend Parler from Amazon Web Services, effective at 11:59 p.m. PST the next day. Echoing Google's rationale for dropping its version of the Parler app, Amazon said Parler's failure to police violent content made the site "a very real risk to public safety". [29] [98] [99] Parler went offline when Amazon withdrew its cloud computing services as scheduled. [28] [100] On January 11, Parler sued Amazon under antitrust law, saying the suspension of services was "apparently motivated by political animus", and had been carried out with the intention of benefiting Twitter by reducing competition. [101] U.S. District Judge Barbara Rothstein ruled in Amazon's favor ten days later. [102] [103] Parler also denied Amazon's claims that it failed to properly moderate content. [104] On March 2, Parler withdrew a federal antitrust lawsuit they had filed against Amazon two months prior, but filed a new lawsuit against the company in state court. The new lawsuit alleged Amazon had breached terms in their contract and defamed Parler. [105] [106] Amid the lawsuit, in mid-April 2021, Amazon accused Parler of trying to conceal its ownership. [107] On September 17, 2021, Seattle federal district Judge Barbara Rothstein approved Parler's request that its complaint against Amazon be heard in King County Superior Court. [108]

Some applauded the technology companies' decisions to deny service to Parler. Others raised concerns about private enterprises determining what remains online. Ben Wizner, a lawyer for the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), told The New York Times that he was concerned about neutrality when it came to Internet infrastructure providers such as Amazon AWS and app stores. [109] Evelyn Douek, a lecturer and content moderation researcher at Harvard Law School, told The Wall Street Journal she thought an argument could be made to defend the infrastructure providers' decision to deny service to platforms who do not adequately moderate content, but wondered if similar amounts of violent content might exist elsewhere in platforms they were serving. [30] Paul Levinson, a professor at Fordham University, wrote in The Conversation that although he believed the de-platforming violated the "spirit of the First Amendment", it was warranted due to the incitement to violence on the Parler site. [110]

After the shutdown, Parler users were reported to have migrated to other alt-tech websites including BitChute, Clapper, CloutHub, DLive, Gab, MeWe, Minds, Rumble, and Wimkin, as well as encrypted messaging services including Telegram and Signal. [111] [112] [113]

Content scraping

Following the storming of the Capitol and just before Parler went offline, a researcher scraped roughly eight terabytes of public Parler posts. The posts scraped made up 99% of publicly-accessible Parler posts, including more than a million videos, which maintained GPS metadata identifying the exact locations where the videos were recorded. The researcher said her intention was to make a public record of "very incriminating" evidence against those who took part in the storming. The data dump was posted online, and the researcher has said the data will eventually be made available by the Internet Archive. [114] [115] According to Ars Technica and Wired, the reason the researcher was able to scrape the data so easily was because the Parler website had poor coding and poor security. [115] [116] According to Wired, although all posts downloaded by the researcher were public, because Parler did not scrub metadata, GPS coordinates of many users' homes had likely been exposed. [116] As of January 15, 2021, Gizmodo had mapped out the locations of around 70,000 of the GPS coordinates linked to videos scraped from Parler. [117] Videos scraped from Parler were used as evidence during the second impeachment trial of Donald Trump. [118]

Investigations

On January 21, 2021, the chairwoman of the House Oversight and Reform Committee, Carolyn Maloney, called for an FBI probe into Parler, including its role in the storming of the Capitol. Maloney said her committee intends to open an investigation into Parler. [119] [120] On February 8, 2021, the committee asked Parler for information relating to who owns or has funded the company, any business ties to Russia, and its alleged offer of an ownership interest in the company to former president Donald Trump during his term. [119] [121]

On August 27, 2021, the U.S. House of Representatives select committee investigating the storming of the Capitol demanded records from Parler (alongside 14 other social media companies) going back to the spring of 2020. [122]

Departure of John Matze

Parler's board, led by Rebekah Mercer, dismissed John Matze from his role as Parler's CEO on January 29. [123] [124] Matze sent a memo to Parler staff in which he said that "I did not participate in this decision" to terminate him and that he had "met constant resistance to [his] product vision, [his] strong belief in free speech and [his] view of how the Parler site should be managed". [45] In interviews following his firing, Matze noted that his termination may have been related to a dispute within the company regarding his belief that the company needed to "crack down" on domestic terrorism and violence and be "a little more pragmatic while still respecting free speech", but he was "not exactly sure" why he had been fired. [125] [126] Matze also said his suggestion to implement a moderation policy to remove extremist content was overruled by Mercer. [123]

Amy Peikoff, Parler's Chief Policy Officer, provided a statement to Fox News in which she disputed Matze's memo to staff as "inaccurate and misleading", though she did not specify to which statements she was objecting. [43] [126] Parler investor Dan Bongino published a video on Facebook after Matze's departure, accusing Matze of "really bad decisions" leading to Parler being taken offline and causing app stability issues, and saying that Matze "decided to make this public, not us. We were handling it like gentlemen." [127]

On February 19, Parler briefly banned Matze's account before restoring it later that day after BuzzFeed News contacted a Parler spokesperson about the banning. [128] This banning came after Matze made a post on Parler asking his followers what they thought the "fair market value" of the company was. [128]

On March 22, in Clark County, Nevada, Matze filed a lawsuit against Parler's board, alleging that Rebekah Mercer and Parler's board members engaged in a scheme to steal Matze's share in Parler. [129]

Return online and subsequent events

Matze wrote in a Parler post on January 9 that Parler could be unavailable for a week as they worked to "rebuild from scratch" and move to a new service provider. [94] In an interview with Fox News on January 10, Matze said Parler had faced trouble in finding a new service provider, contradicting a previous Parler post in which he had said many vendors were vying for their business. [130] He also said others had refused to work with Parler: "Every vendor, from text message services to email providers to our lawyers, all ditched us, too, on the same day." [130] [109] Interviewed by Reuters on January 13, Matze said he did not know if or when Parler would return to operation. [97] On January 17, Matze posted a message on the site's homepage, promising to "welcome all of you back soon". [131] Matze also claimed that Parler could be back online by the end of January. [132]

According to a January 12 Wall Street Journal report, other cloud hosting platforms that could potentially host Parler would be Google Cloud Platform, Microsoft Azure, or the Oracle Cloud platform. As of publication, Parler had not contacted Microsoft, and would not be using Oracle for cloud hosting; Google declined to comment, but the Journal noted that Google had denied Parler a position in the Play Store. The Journal also noted that Parler could consider using smaller cloud hosting companies, but that some technologists doubted such companies' ability to provide stable hosting to such a heavily used service. One such smaller provider, DigitalOcean, let it be known that they would not accept Parler as a customer. [133]

On January 10, Parler transferred their domain name registration to Epik, a domain registrar and web hosting company known for hosting far-right websites such as Gab and Infowars. [134] [133] [135] Vice noted that through this move, Amazon Web Services was again indirectly providing services to Parler, as Epik uses AWS to host many of their DNS servers. [136] On January 17, Parler brought their website back online, hosting only a static page without any of the functionality of the Parler service. [131] Parler's web hosting provider was unknown, [137] but it was noted that they were receiving protection from distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks from the Russian-owned cloud services company DDoS-Guard. [138] [139] [137] This move was criticized in The New York Times and Wired as routing traffic through Russia, and may enable the Russian government to surveil Parler's users and provide data to Russia's Federal Security Service (FSB). [140] [137] Both Epik and DDoS-Guard said they were not providing Parler with webhosting. [141] [137]

The Parler service returned online for existing users on February 15, with a redesigned website and logo, and said they would open the service to new signups the following week. Parler posts from before the service went offline are no longer available. [32] [104] Parler announced that their redesigned site will monitor violent content with human and artificial intelligence and that they will hide posts that attack a person based on sex, sexual orientation, race, or religion with a "trolling filter", however, users are allowed to click through the filter and view the content. [142] Parler's new host is SkySilk Cloud Services, a web infrastructure company based in Los Angeles who said of their hosting of Parler that "Skysilk does not advocate nor condone hate, rather, it advocates the right to private judgment and rejects the role of being the judge, jury, and executioner." [143] [144] SkySilk also said they believe Parler is "taking the necessary steps to better monitor its platform". [104] Mercer helped finance Parler's return online. [145]

On February 25, Apple denied Parler's request to be re-added to the App Store, concluding that the changes Parler had made to their terms of service were not adequate. Apple added that "simple searches reveal highly objectionable content, including easily identified offensive uses of derogatory terms regarding race, religion and sexual orientation, as well as Nazi symbols" on the service. [146]

In late March, Parler claimed in a letter to the House Oversight Committee that "in the days and weeks leading up to January 6th, Parler referred violent content from its platform to the FBI for investigation over 50 times, and Parler even alerted law enforcement to specific threats of violence being planned at the Capitol." [147]

In April, Parler signed up for Salesforce's email services. [148]

A modified version of the Parler app was released on the App Store on May 17. It blocks posts identified by Parler as "hate", though they are still available on the web and on other versions of Parler. The app also includes additional features for reporting "threat[s] and incitement". [149] [150] [34]

In August, Parler CEO George Farmer asked for an apology from Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg and others after a Reuters report said that the FBI found little evidence that the storming of the Capitol was planned and organized in advance. [151]

On September 14, Parler announced that they would sponsor NASCAR Xfinity Series driver J. J. Yeley's No. 17 car during a race at the Las Vegas Motor Speedway later in September. [152]

On December 20, Parler announced that they would expand their business into non-fungible tokens (NFTs). [153]

2022

On January 5, 2022, left-leaning liberal think tank New America released a report titled "Parler and the Road to the Capitol Attack". According to Mother Jones, the report is "a deep and retrospective dive through an estimated 183 million now-public posts" on Parler that discusses Parler's role in the 2021 Capitol attack and the platform's role in the spread of disinformation. [154] [155]

On January 11, a ransomware group joined Parler and started using the platform to aid its extortion efforts. Prior to joining Parler, the group had accounts on Tumblr and Twitter, which were both removed. [156]

On January 22, Farmer claimed that Parler was "unfairly scapegoated" in the aftermath of the Capitol attack and alleged there was a conspiracy against him by Big Tech companies. [3]

On February 9, Parler announced that former First Lady Melania Trump would exclusively use Parler for communications and that the platform would become her "social media home". [157]

In early March, Parler announced that they would launch a marketplace for NFTs called DeepRedSky. [158]

In late June, Tampa Bay lawyer Dale Golden filed a lawsuit against Parler after receiving unsolicited promotional text messages from Parler and alleged that the platform had violated Florida's Telephone Solicitation Act (FTSA). [159]

On September 2, Parler's app became available again on Google Play Store, after Parler reportedly agreed to moderate posts that are shown in the Android version of the app. [35]

Also in September, Parler announced a restructuring of their platform and company that would focus on providing services to businesses that have the potential of being forced off the Internet for hosting controversial content. Toward that end, they created a new parent company, Parlement Technologies Inc., which purchased Dynascale Inc., a cloud service provider. [160]

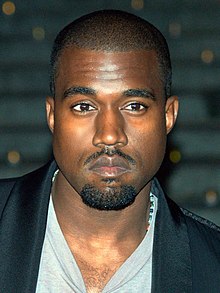

Kanye West purchase bid

On October 17, Parler's parent company stated that Kanye West had agreed to buy ownership of the platform. This came after West was blocked from Instagram and Twitter for antisemitic remarks. [161] The deal was expected to close in the fourth quarter of 2022, [10] but was terminated in December by mutual agreement. [162] Parler accidentally doxxed over 300 of its VIP members by including their email addresses in its announcement of West's purchase. [163]

2023 acquisition and shutdown

On April 14, 2023, digital media conglomerate Starboard announced that it had acquired Parler's parent company Parlement Technologies, and that it would temporarily shut down the social site while it prepared a revamped version. [36]

The website's home page was initially replaced with a holding page containing a statement by Starboard saying that "No reasonable person believes that a Twitter clone just for conservatives is a viable business any more" and that "the Parler app as it is currently constituted will be pulled down from operation to undergo a strategic assessment". [164] For a period of time, the page was a simple purple/pink background emblazoned with the Parler brand and logo, and a message that read, "Coming Soon."

2024 relaunch

On February 9, 2024, Parler's social media outlets announced a relaunch of the social media service, simultaneously updating the website with a form to allow visitors to register for announcements regarding the platform's reopening. [165] [166]

Usage

Parler had fewer than a million users until early 2020. [167] In the last week of June 2020, it was estimated that the Parler app had more than 1.5 million daily users. [61] As of July 15, 2020 [update], Parler had 2.8 million total users and had been downloaded 2.5 million times, nearly half of which were in June. [19] [51] Throughout June and July, Parler on several occasions was highly listed both on the Apple App Store and on the Google Play store, in various categories and overall. [22] The Parler app was downloaded nearly a million times in the week following Election Day in the United States on November 3, and became the most popular free app both on the Apple App Store and on the Google Play Store. [75] Parler remained the most downloaded app in the United States for five days in early November. [81] The New York Times reported that Parler had added 3.5 million users in a single week, [168] and during that month the service had about four million active users, and more than ten million total. [74] [2] In December 2020, Parler had around 2.3 million daily active users. [78] Fast Company reported that, as of December 5, both the number of daily active users and the rate of new downloads had dropped from their November peak, and CNN reported on December 10 that downloads had "plummeted" and were returning to the numbers Parler was experiencing before the election. [77] [78] Parler again topped the App Store downloads chart on January 8, 2021, shortly after then-President Trump was permanently suspended from Twitter and also shortly before Parler was removed from the App Store by Apple. [90] [94] As of January 2021, Parler reported having 15 million total users. [30] According to Sensor Tower, Parler has received 11.3 million global downloads from both the App Store and the Play Store. [169] Also according to Sensor Tower, app downloads for Parler had dropped from 517,000 in December 2020 to 11,000 in June 2021. [170] According to a May 2022 Pew Research Center poll, 38 percent of American adults have heard of Parler, while only 1 percent regularly get their news from Parler. [171]

Despite the wave in signups in mid-2020, and the larger surge in November of that year, some journalists and researchers expressed doubt that Parler will remain popular or enter mainstream usage. According to TheWrap, after several weeks of more than 700,000 downloads a week, Parler's weekly downloads subsided back into the low 100,000s during mid-July. [172] Bloomberg News also reported that downloads of the app had substantially slowed following the initial mid-2020 wave, and described Parler's June download numbers as a "small fraction" of apps like TikTok, which receives tens of millions of downloads a month. [51] Parler's user base, though it grew substantially in mid- and late 2020, remained much smaller than its competitors'. [19] [20] [48] As of November 2020 [update], Twitter had 187 million users a day and Facebook had 1.8 billion users a day, whereas Parler had four million active users and eight million total. [74] Slate wrote that alternative social networks like Parler "normally ... just don't get that big." [22] When Parler's download and usage activity diminished following the November surge in popularity, the vice president of insights at the app analytics company Apptopia said to CNN, "The data trends resemble a fad, and a short-lived one at that ... Parler had a very good spike. People were interested, it's in the news, it receives downloads. ... But it appears, in our data, that there is no staying power." [78]

Although some high-profile figures have created accounts on Parler, many of them remain more active, and have substantially larger follower bases, on mainstream social networks. [14] [19] [48] [173] Mic questioned how long Parler's spike in popularity would last, citing as an obstacle the reluctance among those with large Twitter followings to migrate to a new service. [55] The Daily Beast noted in July and October 2020 that many high-profile conservatives who opened accounts on Parler in the previous month had since stopped using the service, while remaining active on mainstream social networks. [174] [175] Some have described Parler as a backup in case Twitter bans them. [51] [174] CNN interviewed Trump supporters in December 2020 about their social media use and found that "almost none" had completely abandoned Twitter and Facebook. [176] The same month, OneZero reported that Parler users were gathering in Facebook groups to complain that Parler's interface was difficult to operate, to share concerns about having to submit identification to be verified, and to express regrets that their friends and family had not joined. [177]

User base

Parler has a significant user base of conservatives. [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] The app also has a number of high-profile Republican users, including Senators Rand Paul and Ted Cruz, as well as Fox News host Sean Hannity. [61] [85] The Anti-Defamation League wrote in November 2020 that "Parler has attracted a range of right-wing extremists" including Proud Boys; proponents of the QAnon conspiracy theory; anti-government extremists including members of the Oath Keepers, Three Percenters, and other militia groups; and white supremacists including members of the alt-right and far-right accelerationists such as the terrorist group Atomwaffen Division. [13] [167] Leaked GPS coordinates from Parler also revealed that users of the site include police officers in the United States and members of the U.S. Armed Forces. [178] Parler was also used by at least 14 UK Conservative Party Members of Parliament; several ministers including cabinet minister Michael Gove and a number of prominent UK conservative commentators joined the app. [179] Some right-wing news companies including Breitbart News, The Epoch Times, and The Daily Caller also had accounts on Parler. [180]

Researchers, journalists, and Parler users have observed the lack of ideological diversity on the service, [81] [48] [181] and that Parler has served as an echo chamber for right-wing extremists and Trump supporters. [187] In mid-2020, alt-right activist and Trump supporter Jack Posobiec compared the service to a Trump rally, saying Parler lacks the "energy" Twitter draws from having communities of people with differing viewpoints. [48] [181] Around the same time, extremism researcher and professor Amarnath Amarasingam said of Parler, "talking to yourself in the dark corners of the internet is actually not that satisfying," and that he was skeptical Parler would excite the far right without left-leaning users with whom they can interact and fight. [22] In June 2020, Matze said he wanted to see more debate on the platform and offered a "progressive bounty" of $10,000 to liberal pundits with at least 50,000 Twitter or Facebook followers who would join; receiving no takers, he later increased this amount to $20,000. [48] [61]

Jason Blazakis, the director of the Center on Terrorism, Extremism, and Counterterrorism at the Middlebury Institute, told The Hill in November 2020 that he thought extremist users migrating to Parler was a good thing: "these people are leaving those platforms and no longer trying to red pill individuals to see their conspiracy theories on large platforms like Facebook and Twitter." He said Parler's size might result in a smaller audience for those pushing conspiracy theories and spreading misinformation. [188] Angelo Carusone, president of the progressive media watchdog group Media Matters for America, has said of Parler, "The self-segmenting of this group to Parler will intensify their extremism. No doubt about that. But it will also weaken the influence of the right wing by siphoning off a segment of users, many of whom will be the most engaged users." [185]

Parler is one of a number of alternative social network platforms, including Gab and BitChute, that are popular with people banned from mainstream networks such as Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Reddit, and Instagram. [189] [190] Deen Freelon and colleagues writing in Science characterized Parler as among alt-tech websites and services that are "dedicated to right-wing communities", and listed the service along with 4chan, 8chan, BitChute, and Gab. They noted there are also more ideologically neutral alt-tech services, such as Discord and Telegram. [191] Joe Mulhall of the UK anti-racism group Hope Not Hate has categorized Parler among the "bespoke platforms" for the far-right, which he defines as platforms which were created by people who themselves have "far-right leanings". He distinguishes these from "co-opted platforms" such as DLive and Telegram, which were adopted by the far-right due to minimal moderation but not specifically created for their use. [192]

Content

Parler is known for its conservative content. [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [ excessive citations]Parler has said they will not fact-check posts on the platform, a decision BBC News in 2020 says has allowed misinformation to spread more easily on the platform than on mainstream social networks. In particular, BBC News noted the presence of posts spreading the QAnon conspiracy theory, as well as misinformation surrounding the 2020 U.S. presidential election, COVID-19, child trafficking, and vaccines. [72] The Verge noted in November 2020 that Parler had become a "central hub" for the Stop the Steal conspiracy theory relating to the 2020 U.S. presidential election. [75] In 2019 and 2020 respectively, The Forward and The Bulwark observed the presence of antisemitic conspiracy theories as well as others. [14] [193] An analysis of posts from the week leading up to the Capitol storming found that 87% of the links shared on Parler were to misinformation websites, including Islamophobic and QAnon sites. [194] According to Stanford University's Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, Parler had become an "echo chamber" for "unfounded conspiratorial allegations of deliberate theft and plotting". [3]

Matze told The Forward in 2019 that he was unaware of antisemitic content on Parler, but he was unsurprised it was there. He believes removing hateful content only further radicalizes people, saying, "If you're going to fight these peoples' views, they need to be out in the open. ... Don't force these people into the corners of the internet where they're not going to be able to be proven wrong." [14] Extremism expert Chip Berlet said of Matze's opinions on hateful content: "I think he's full of it. ... I think he knows exactly what he's creating, he's encouraging people who basically don't like other folks in the country ... it's balogna, this is a place for people to fester in their own bigotry." [14] In December 2020, the Houston Chronicle argued that "Beneath the thin guise of the app’s self-proclaimed emphasis on 'free speech' lies the ability to say not just a hypothetical 'anything,' but specifically to share racist slurs and violent threats toward political opponents." [15] Political scientist Alison Dagnes has said of Parler's stance on speech on the platform: "I don't think you can have it both ways. ... There is no such thing as civilized hate speech." [14]

In late 2020, Parler revised their site guidelines, which had previously prohibited pornography and obscenity, to permit the posting of "adult sex or nudity". [55] [195] A review by The Washington Post in December that year found that pornography was "surging" on Parler, and "threaten[ed] to intrude on users not seeking sexual material". The Post observed that pornographic videos began playing without label or warning, and that a filter to label and require an additional click to view explicit content was not being uniformly applied to pornographic images. The report also noted that conspiracy theory content overlapped with pornography, observing that searches for QAnon-related hashtags retrieved "numerous pornographic images". [195] [81] [196]

A study co-written by Annalise Baines, Muhammad Ittefaq and Mauryne Abwao published in the journal Vaccines found that Parler provided an echo chamber for vaccine misinformation and conspiracy theories. [197] [198]

Moderation

Parler describes itself as a free speech platform, and its founders have proclaimed that the service engages in minimal moderation and will not fact-check posts. They have also said they will allow posts that have been removed or flagged as misinformation on other social media networks such as Twitter. [19] [20] Matze said in an interview with CNBC on June 27, 2020, "We're a community town square, an open town square, with no censorship ... If you can say it on the street of New York, you can say it on Parler." [61] The service has been popular among conservatives who allege Twitter and Facebook has been biased against them when moderating content or flagging misinformation, praising Parler for offering an alternative to these mainstream platforms. [23] [72] [61] [199][ excessive citations]

However, the site has been criticized by users and journalists who believe its content policies are more restrictive than the company portrays, and sometimes more restrictive than those of the mainstream social media platforms to which it claims to be an unbiased free speech alternative. [56] [21] [22] [200] [ excessive citations]Parler's guidelines disallow content including blackmail, support for terrorism, false rumors, promoting marijuana, and "fighting words" directed towards others. [52] [61] The site initially forbade the posting of pornography, obscenity, or indecency, but later modified its guidelines to allow the posting of "adult sex or nudity". [195] [23] Parler says their moderation policy is based on the positions of the United States Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and Supreme Court, although Gizmodo has described this as "nonsensical", noting that the FCC moderates only public airwaves, not internet content, and that some of Parler's rules are more restrictive than restrictions imposed by either the FCC or the Supreme Court. [21] The Independent wrote in November 2020, "Despite positioning itself as a libertarian platform promoting freedom of expression, Parler's community guidelines are more than 1,500 words and include rules that go far beyond legal requirements." [201] Wired wrote in November 2020 that Parler enforced its guidelines inconsistently, and that the service either "prioritizes conservative speech rather than free speech" or "is set up to amplify its influencers, rather than create a space for anyone to be heard". [202]

In June and July 2020, Parler banned a spate of left-wing accounts, including parody accounts and accounts that were critical of Parler or the prevailing viewpoints on the service. [19] [52] [203] [204] Mic wrote that Parler had used the personal information provided during signup to ban those they had identified as "teenage leftists"; [55] Will Duffield of the Cato Institute wrote that Matze had also apparently instituted a blanket ban on antifa supporters. [205] After a surge in popularity among conservatives in November 2020, The Independent noted that Parler had again been accused of removing left-leaning users and removing content that contradicted or was critical of popular opinions expressed there. [201] In January 2021, Ethan Zuckerman and Chand Rajendra-Nicolucci wrote in a report for the Knight First Amendment Institute that Parler's invitation on its front page, "'Speak freely and express yourself openly, without fear of being "deplatformed" for your views,' often isn't borne out in reality as Parler regularly bans trolls who hold opposing viewpoints." [206]

On June 30, 2020, after the wave of bans, Matze published a Parler post outlining some of the service's rules. [19] [21] Some of them, such as one asking users not to publish photos of feces, were described by The Independent as "bizarre". [207] Slate and Gizmodo noted that the top reply to Matze's post identified that "Twitter allows four of the five things that Parler censors." [21] [22] Some of the clauses in Parler's user agreement have been criticized as "unusual" and seemingly contradictory to its mission, including one that allows Parler to remove content and ban users "at any time and for any reason or no reason", and one that would require a user to pay for any of Parler's legal expenses incurred as a result of their use of the service. [20] [22] [52] [174] [ excessive citations]Ars Technica reported in November 2020 that the clause requiring users to cover legal fees had been removed from Parler's user agreement following negative media coverage. [208]

Matze told The Washington Post he does not see Parler's guidelines as contradictory to its stance on free speech. [19] As of July 2020 [update], Parler had a team of 200 volunteer moderators. [19] Matze told Fortune magazine the same month that he wanted to expand the moderation team to 1,000 volunteers. [54] In November 2020, The Wall Street Journal reported all moderation was still being handled by volunteers, which Parler calls "community jurors". [2] In January 2021, The Wall Street Journal reported that Parler had increased its moderation team to 600 people, and began paying them. They also had begun hiring full-time employees to moderate the service. [30]

In January 2021, Parler executives acknowledged that rules-violating content had remained on the platform, which they attributed to their volunteer team of moderators being overwhelmed by large backlogs of posts to review. Parler executives also reported there had been an increase in calls for violence on the platform leading up to the riots at the Capitol. Parler's chief of policy, Amy Peikoff, told The Wall Street Journal she had directed moderators to report such threats to law enforcement, and that she "was concerned that there was actually going to be some sort of violence on the 6th". [30]

Appearance and features

Parler is a microblogging service that is both a website and an app. After being removed from the Apple App Store in January 2021, a version of the app with added content filters was released in May 2021. The app was formerly available on the Google Play Store, but was also removed in January 2021. [207] Users who register for accounts are able to follow the accounts of other users. [209] Unlike Twitter, the feed of posts – called "parleys" – from followed accounts appears to a user chronologically, instead of through an algorithm-based selection process. [51] [209] [210] Parleys are limited to 1,000 characters in length, and users can "vote" or "echo" the posts of other users whom they follow, functions that have been compared to Twitter's "like" and "retweet" functions. [20] A direct messaging feature is also built into the platform, allowing users to privately contact each other. [20] Public figures are verified on the app with a gold badge, and parody accounts are identified with a purple badge. [61] Anyone who verifies their identity by providing government-issued photo identification during signup is identified with a red badge. [20] Spammers have exploited this two-tier verification system by providing documentation to verify their identity, obtaining a red badge, and changing their account name. The red badge persisted after the name change. [211] Parler refers to users of its service as Parleyers. [19]

Forbes described Parler as "like a barebones Twitter" in June 2020. [209] The same month, Fast Company wrote that Parler was "well-designed and organized", also noting its similarity to Twitter. [183] The Conversation described the service in July 2020 as "very similar to Twitter in appearance and function, albeit clunkier". [212] CNN has said Parler resembles a "mashup of Twitter and Instagram". [78] [213]

Registration and verification

Creating an account and using Parler is free. Signup requires both an e-mail address and a phone number. [55] At the point of registration, users have the option of supplying a photo of themselves and a scan of the front and back of their government-issued photo identification to have their account verified by Parler. [210] [20] In order to join Parler's "influencer network", the company may ask for users' social security or tax identification numbers. [204]

According to Matze, the identification document scans submitted by users who choose to have their accounts verified are destroyed after verification. However, the requirement for ID scans to become verified has prompted conspiracy theories about Parler's retention and use of user information. [210] [214] Matze has also said the service requires users to provide their phone number because people who can stay anonymous online say "nasty things". [204]

Individual users can optionally set their account to view Parleys only from other verified users. According to Matze, the purpose of the verification feature is to allow users to minimize their contact with trolls and bots. [210] [215]

Security

Several publications and researchers have criticized Parler's security.

In November 2020, security researcher Aubrey Cottle renamed an already-verified Parler account to spoof the identity of Ron Watkins, the former site administrator of 8chan. Speaking to The Washington Post after the hoax, Cottle described Parler's security as a "joke". [23] The Daily Dot also described "what appeared to be some pretty serious security flaws" in Parler in a report pertaining to the incident. [82] Watkins himself was vocally critical of Parler and its security on Twitter after the spoofing incident, describing the service as "compromised". [81] [82]

Also in mid-November, security researcher Kevin Abosch claimed to have discovered weaknesses in Parler's user verification information, alleging 5,000 accounts were compromised in July 2020. Matze calling the alleged hack "fake", adding that the service is protected by "multiple layers of security". [216] [217] [218] As of late November, no evidence that the site used vulnerable WordPress technology as claimed had surfaced. [219] [220]

In January 2021, following the storming of the Capitol and just before Parler went offline, a researcher scraped roughly eighty terabytes of public Parler posts. The scraped data included more than a million videos, which maintained GPS metadata identifying the exact locations where the videos were recorded, as well as text and images. Some of the data included posts that users had attempted to delete. [221] [114] The researcher stated her intention was to make a public record of "very incriminating" evidence against those who took part in the storming. The data dump was posted online, and the researcher has said the data will eventually be made available by the Internet Archive. [114] [115] According to Ars Technica and Wired, the reason the researcher was able to scrape the data so easily was due to the Parler website's poor coding quality and security flaws. There was no authentication or rate limiting on the API, and deleted posts were "soft deleted": a flag was added to hide them, but they were not actually deleted. [115] [116] [222] According to Wired, although all posts downloaded by the researcher were public, because Parler didn't scrub metadata, GPS coordinates of many users' homes had likely been exposed. [116]

Company

Parler was founded in 2018 by John Matze and Jared Thomson. In November 2020, The Wall Street Journal reported that Rebekah Mercer, an investor known for her support of conservative individuals and organizations, had helped fund Parler. After the report was published, Mercer described herself as having "started Parler" with Matze, and she has been described by CNN as a co-founder of the company. [2] [1] [40]

Parler has not disclosed the identities of its owners; however, Dan Bongino publicly announced in June 2020 that he had purchased an "ownership stake" of unspecified value. [20] [50] In November 2020, Matze wrote in a Parler post that Parler was owned by "myself, a small group of close friends and employees", and had as investors Bongino and Parler chief operating officer Jeffrey Wernick [74] In November 2020, a manipulated image circulated on social media of a Fox News chyron that appeared to report that George Soros, a billionaire philanthropist and the frequent target of antisemitic conspiracy theories, was a majority owner of Parler. Soros does not own Parler and Fox News never reported the claim; the image had been digitally altered from a photo of a television showing a Fox broadcast about a different subject. [223] [224] [202]

On January 29, 2021, Parler's board, controlled by Mercer, terminated Matze from his position as CEO. [45] In a memo Matze sent to Fox Business, he claimed that "I did not participate in this decision" to terminate him and that he had "met constant resistance to [his] product vision, [his] strong belief in free speech and [his] view of how the Parler site should be managed". [45] In interviews, Matze said his termination may have been related to a dispute within the company regarding the limits of free speech and his belief that the company needed to "crack down" on domestic terrorism and violence. [125] [45] Matze also had all his Parler shares stripped from him when he was fired. [225] With Matze gone, an executive committee of Mercer, British lawyer Matthew Richardson, and former Tea Party activist Mark Meckler runs the company. [226] [43] Parler announced on February 15, 2021, that Mark Meckler would serve as the company's interim CEO while they searched for someone to take the position. [32] [227] Parler announced on May 17, 2021, that they had named George Farmer as CEO. Farmer is a former candidate for and financial supporter of the Brexit Party (now known as Reform UK) in the United Kingdom. [228] [229] Prior to joining Parler, Farmer worked at Red Kite, a hedge fund founded by his father Michael Farmer, Baron Farmer, a former treasurer of the United Kingdom's Conservative Party, and was the former head of Turning Point UK, a British offshoot of the American conservative nonprofit organization Turning Point USA. [44]

On March 2, 2021, NPR reported that Parler's lawyers had written in a legal filing that the company's valuation was "approaching $1 billion". [225]

On October 12, 2021, Parler announced in an email that they would be moving their headquarters from Henderson, Nevada to Nashville, Tennessee. [230] [231]

Seth Dillon, the CEO of conservative Christian news satire website The Babylon Bee, has been listed as a director of Parler. [232]

As of November 2020 [update], Parler had about thirty employees. [2]

On December 15th, Parler was bought from Starboard by Ryan Rhodes, Elise Pierotti and Jaco Booyens. [39]

Funding

In a June 27, 2020, interview with CNBC, Matze said he wanted to raise an institutional round of financing soon, although he expressed concerns that venture capitalists might not be interested in funding the company because of ideological differences. [61] Fortune wrote in June 2020 that the company planned to add advertising to the service soon. [20] They also planned to generate revenue based on an ad matching scheme whereby companies would be matched with Parler influencers to post sponsored content, with Parler taking a percentage of each deal. [20] [209] Slate has questioned Parler's business model, writing that Parler's plan to rely on advertising revenue "seems far from foolproof" given the 2020 advertising boycotts of Facebook by some large brands who objected to hateful content on the platform. [22] NBC also questioned whether corporations would be interested in advertising alongside "controversial material" on Parler. [74] Matze said in an interview on June 29, 2020, that the business was not profitable. [233] As of January 2021 [update], Parler had not received any known venture capital, although in February 2021, Buzzfeed News reported that Parler had recently sought to obtain funding from J. D. Vance's venture-capital firm Narya Capital. [74] [222] [43] In January 2022, Parler raised $20 million in funding. [232]

In September 2022, Parler announced $16M in Series B funding, for a total of $56M in funding to date. [234]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e Benveniste, Alexis; Yurieff, Kaya. "Meet Rebekah Mercer, the deep-pocketed co-founder of Parler, a controversial conservative social network". CNN. Archived from the original on November 15, 2020. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Horwitz, Jeff; Hagey, Keach (November 14, 2020). "Parler, Backed by Mercer Family, Makes Play for Conservatives Mad at Facebook, Twitter". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ^ a b c Jones, Callum (January 22, 2022). "From the flag-bearer for free speech to 'scapegoat', Parler is fighting back". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved January 22, 2022.

- ^ "Social media platform Parler is back online on 'independent technology'". CNBC. February 15, 2021. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ^ a b Murdock, Jason (June 25, 2020). "Who Owns Parler? Social Media Platform Offers Safe Space for the Far Right". Newsweek. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ "Parler Is Dead, but Trump Is Still Using Its Newsletter to Raise Cash and Own the Libs". Yahoo Sports. June 16, 2023. Retrieved November 14, 2023.

- ^ a b c Fung, Brian (October 17, 2022). "Kanye West to acquire conservative social media platform Parler". CNN. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Kanye West agrees to buy right-wing platform Parler". BBC News. October 17, 2022. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c Browne, Ryan (October 17, 2022). "Kanye West, who now goes by Ye, agrees to buy conservative social media platform Parler, company says". CNBC. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Kanye West to buy conservative social media app Parler". Al Jazeera. October 17, 2022. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c Coster, Helen; Datta, Tiyashi; Balu, Nivedita (October 17, 2022). "Kanye West agrees to buy social media app Parler". Reuters. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ Turner, Giles (October 17, 2022). "Ye to Buy Controversial Social Networking App Parler". Bloomberg. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ a b "Parler: Where the Mainstream Mingles with the Extreme". Anti-Defamation League. November 12, 2020. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Saul, Isaac (July 18, 2019). "This Twitter Alternative Was Supposed To Be Nicer, But Bigots Love It Already". The Forward. Archived from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ a b Parker, Bryan C. (December 1, 2020). "I tried Parler, the social media app where hate speech thrives". Chron. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Culliford, Elizabeth; Paul, Katie (June 14, 2019). "Unhappy with Twitter, thousands of Saudis join pro-Trump social network Parler". Reuters. Archived from the original on June 27, 2019. Retrieved June 15, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Di Stefano, Mark; Spence, Alex; Mac, Ryan (February 12, 2019). "Pro-Trump Activists Are Boosting A Twitter App Used By Banned Personalities And It Appears To Have Already Stalled". BuzzFeed News. Archived from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ Wilson, Jason (January 13, 2021). "Rightwingers flock to 'alt tech' networks as mainstream sites ban Trump". The Guardian. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lerman, Rachel (July 15, 2020). "The conservative alternative to Twitter wants to be a place for free speech for all. It turns out, rules still apply". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Pressman, Aaron (June 29, 2020). "Parler is the new Twitter for conservatives. Here's what you need to know". Fortune. Archived from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Cameron, Dell (June 30, 2020). "Parler CEO Says He'll Ban Users for Posting Bad Words, Dicks, Boobs, or Poop". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on July 1, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hadavas, Chloe (July 3, 2020). "What's the Deal With Parler?". Slate. Archived from the original on July 3, 2020. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Harwell, Drew; Lerman, Rachel (November 23, 2020). "Conservatives grumbling about censorship say they're flocking to Parler. They told us so on Twitter". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- ^ a b Jaehnig, Johnathan (May 31, 2022). "Is Parler Back Online?". MakeUseOf. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ Simeone, Michael; Walker, Shawn (July 7, 2022). "How "Big Tech" Became the Right Wing's 2020 Boogeyman". Slate. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ "Parler social network sues Amazon for pulling support". BBC News. January 11, 2021. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ Nicas, Jack; Alba, Davey (January 10, 2021). "Apple and Google Cut Off Parler, an App That Drew Trump Supporters". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 10, 2021. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ a b "Parler social network drops offline after Amazon pulls support". BBC News. January 11, 2021. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ a b c Paczkowski, John (January 9, 2021). "Amazon Is Booting Parler Off Of Its Web Hosting Service". BuzzFeed News. Archived from the original on January 10, 2021. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hagey, Keach; Horwitz, Jeff (January 11, 2021). "Parler, a Platform Favored by Trump Fans, Struggles for Survival". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ Abril, Danielle (January 19, 2021). "Meet Epik, the right-wing's best friend online". Fortune. Archived from the original on January 19, 2021. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- ^ a b c Robertson, Adi (February 15, 2021). "Parler is back online after a month of downtime". The Verge. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Lonas, Lexi (February 15, 2021). "Parler announces official relaunch, says it is back online". TheHill. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ a b Molina, Brett (May 17, 2021). "Parler is back on iPhones: Social media app returns to Apple's App Store". USA Today. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ a b Fischer, Sara (September 2, 2022). "Google brings Parler back to Google Play Store". Axios. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ a b "Conglomerate Starboard buys Parler, to shut down social media app temporarily". Reuters. April 14, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Parler". parler.com. April 14, 2023. Archived from the original on April 15, 2023. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- ^ "Index of /". parler.com. November 14, 2023. Archived from the original on November 14, 2023. Retrieved November 14, 2023.

- ^ a b "Conservative social media app Parler planning to relaunch ahead of 2024 election". NBC News. December 18, 2023. Retrieved March 6, 2024.

- ^ a b c Lyons, Kim (November 14, 2020). "Social app Parler apparently receives funding from the conservative Mercer family". The Verge. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Schreckinger, Ben (May 28, 2019). "Amid censorship fears, Trump campaign 'checking out' alternative social network". Politico. Archived from the original on June 19, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019.

- ^ McKay, Tom (November 9, 2020). "'Free Speech' Social Network Parler Tops App Store Downloads After Trump Loses Election". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on November 15, 2020. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mac, Ryan; Gray, Rosie (February 5, 2021). "Donald Trump's Business Sought A Stake In Parler Before He Would Join". Buzzfeed News. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- ^ a b Murphy, Hannah (September 14, 2021). "George Farmer seeks to revive 'free speech' app that imploded after US Capitol riots". Financial Times. Retrieved September 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Flood, Brian (February 3, 2021). "Parler CEO John Matze says he's been terminated by board: 'I did not participate in this decision'". Fox Business. Archived from the original on February 3, 2021. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c Rothschild, Mike (June 25, 2019). "Parler wants to be the 'free speech' alternative to Twitter". The Daily Dot. Archived from the original on June 27, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ Needleman, Sarah E. (March 11, 2021). "What is Parler? Conservative Social-Media App Denied Apple's App Store Access". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on March 12, 2021. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Nguyen, Tina (July 6, 2020). "'Parler feels like a Trump rally' – and MAGA world says that's a problem". Politico. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ a b c Brownlee, Chip (June 14, 2020). "Saudis Fed Up With Twitter "Censorship" Jump Ship to a Pro-Trump Social Media Site". Slate. Archived from the original on June 25, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ a b c Colton, Emma (June 24, 2020). "Conservatives fed up with 'censorship' on Twitter jump to Parler". Washington Examiner. Archived from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Brustein, Joshua (July 15, 2020). "Social Media App Parler, a GOP Darling, Isn't Catching On". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on July 17, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Watts, Marina (June 30, 2020). "Parler, the Ted Cruz-Approved 'Free Speech' App, is Already Banning Users". Newsweek. Archived from the original on July 5, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ Ghaffary, Shirin (July 30, 2020). "Why Facebook and Twitter won't fact-check Trump's latest false claims about voting". Vox. Archived from the original on August 2, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ a b Abril, Danielle (July 1, 2020). "Conservative social media darling Parler discovers that free speech is messy". Fortune. Archived from the original on August 13, 2020. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Yune, Tebany (June 29, 2020). "What is Parler and why won't conservatives shut up about it?". Mic. Archived from the original on November 10, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Manavis, Sarah (June 23, 2020). "What is Parler? Inside the pro-Trump "unbiased" platform". New Statesman. Archived from the original on June 25, 2020. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ "Katie Hopkins permanently suspended from Twitter". BBC News. June 19, 2020. Archived from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ Goforth, Claire (June 22, 2020). "After far-right pundit suspended from Twitter, impersonator raises money for BLM". The Daily Dot. Archived from the original on June 23, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ Sugden, Maureen (June 26, 2020). "Issue of the day: What is Parler?". The Herald. Archived from the original on June 27, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ Glazer, Emily; Bender, Michael C. (June 24, 2020). "Trump Campaign Weighs Alternatives to Big Social Platforms". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on July 8, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Levy, Ari (June 27, 2020). "Trump fans are flocking to the social media app Parler – its CEO is begging liberals to join them". CNBC. Archived from the original on June 27, 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ Peters, Jay (June 28, 2021). "Parler reportedly refused to ban Trump's critics as part of discussions to bring him onboard". The Verge. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ Lima, Cristiano (June 25, 2020). "Cruz joins alternative social media site Parler in swipe at big tech platforms". Politico. Archived from the original on July 2, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ Boadle, Anthony (September 27, 2017). "Far-right presidential hopeful aims to be Brazil's Trump". Reuters. Archived from the original on November 10, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ a b c Oliveira, Felipe (July 13, 2020). "Parler: rede social adotada por Bolsonaro facilita circulação de fake news" [Parler: Bolsonaro's social network facilitates circulation of fake news]. Universo Online (in Brazilian Portuguese). Archived from the original on July 17, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ Lyons, Kim (March 30, 2020). "Twitter removes tweets by Brazil, Venezuela presidents for violating COVID-19 content rules". The Verge. Archived from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ a b Timberg, Craig (October 7, 2020). "Parler and Gab, two conservative social media sites, keep alleged Russian disinformation up, despite report". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 19, 2020. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ^ Dorfman, Zach (October 7, 2020). "Russia eyes far-right U.S. social media networks". Axios. Archived from the original on October 10, 2020. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ^ Stubbs, Jack (October 1, 2020). "Exclusive: Russian operation masqueraded as right-wing news site to target U.S. voters – sources". Reuters. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

-

^

- Guglielmi, Giorgia (October 28, 2020). "The next-generation bots interfering with the US election". Nature. 587 (7832): 21. Bibcode: 2020Natur.587...21G. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-03034-5. PMID 33116324.

- Neiwert, David (January 17, 2018). "Conspiracy meta-theory 'The Storm' pushes the 'alternative' envelope yet again". Southern Poverty Law Center. Archived from the original on February 22, 2020. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- Collins, Ben; Zadrozny, Brandy (August 10, 2018). "The far right is struggling to contain Qanon after giving it life". NBC News. Archived from the original on February 6, 2020. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- Rosenberg, Eli (November 30, 2018). "Pence shares picture of himself meeting a SWAT officer with a QAnon conspiracy patch". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 24, 2020. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- Iannelli, Jerry (November 30, 2018). "Broward SWAT sergeant has unauthorized 'QAnon' conspiracy patch at airport with VP, report says". Miami New Times. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- Moore, McKenna (August 1, 2018). "What You Need to Know About Far-Right Conspiracy QAnon". Fortune. Archived from the original on December 17, 2019. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- Roose, Kevin (July 10, 2019). "Trump Rolls Out the Red Carpet for Right-Wing Social Media Trolls". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 11, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ Timberg, Craig; Stanley-Becker, Isaac. "QAnon learns to survive – and even thrive – after Silicon Valley's crackdown". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 19, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Sardarizadeh, Shayan (November 9, 2020). "Parler 'free speech' app tops charts in wake of Trump defeat". BBC News. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- ^ Schiffer, Zoe (November 6, 2020). "'Stop the Steal' spreads across the internet after infecting Facebook". The Verge. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Ingram, David (November 10, 2020). "A Twitter for conservatives? Parler surges amid election misinformation crackdown". NBC News. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- ^ a b c Brandom, Russell (November 9, 2020). "Parler, a conservative Twitter clone, has seen nearly 1 million downloads since Election Day". The Verge. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

-

^

- Sullivan, Mark (November 5, 2020). "The pro-Trump 'Stop the Steal' movement is still growing on Facebook". Fast Company. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- Beckett, Lois (November 6, 2020). "Tea party-linked activists protest against 'election fraud' in US cities". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 7, 2020. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ^ a b Dishman, Lydia (December 7, 2020). "Conservative playgrounds Parler and MeWe are not sustaining their pre-election growth". Fast Company. Archived from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Yurieff, Kaya (December 10, 2020). "Conservatives flocked to Parler after the election. But its explosive growth is over". CNN. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- ^ Shalvey, Kevin (January 29, 2021). "Parler registered 7,029 new users per minute during the November election, say Stanford researchers". Business Insider. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- ^ Stanley, Alyse (November 15, 2020). "Wait, Did Ron Watkins Just Rat Out His Dad, 8Kun's Jim Watkins, as Q?". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on December 17, 2020. Retrieved December 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Gilbert, David (December 11, 2020). "Even QAnon Is Abandoning Parler, the Far-Right's Answer to Twitter". Vice News. Archived from the original on December 11, 2020. Retrieved December 12, 2020.