Between 1923 and 1936, the Imperial War Graves Commission erected a series of memorial tablets in French and Belgian cathedrals to commemorate the British Empire dead of the First World War. The tablets were erected in towns in which British Army or Empire troops had been quartered.

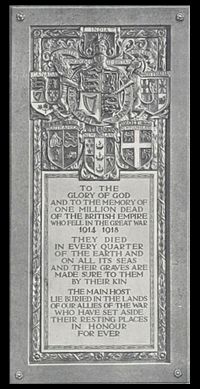

The prototype Commission memorial tablet, placed in Amiens Cathedral in 1923 alongside tablets previously erected to other Empire troops, was dedicated to the 600,000 dead of Britain and Ireland. The subsequent design of the Commission's tablet brought together the British Royal Coat of Arms with those of India and the imperial dominions: South Africa, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and Newfoundland. The tablet's inscription, written by Rudyard Kipling, referred to the "million dead" of the Empire. Produced by Reginald Hallward to a design by architect H. P. Cart de Lafontaine, the tablets were erected in twenty-eight cathedrals and churches, twenty-three in France and five in Belgium, with the bilingual inscriptions in each country in English and French, and English and Latin respectively. They were unveiled by a range of dignitaries, including members of the royal family, diplomats, politicians, and British Army generals who had commanded troops on the Western Front.

A tablet of the same design, but with an inscription referring to the dead buried in the "lands of our Allies", was unveiled in Westminster Abbey in 1926 and later installed in what became St George's Chapel. Replicas or copies of the Westminster Abbey tablet were distributed to churches or cathedrals in Hamilton and Vancouver in Canada, and in Baghdad in Iraq. Copies or reproductions are located at the museum at Delville Wood in France, in Fremantle, Australia, and in Liverpool, UK. Versions of the prototype Amiens tablet and the standard tablet used in France are held at the headquarters of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in Maidenhead, UK.

Origin and design

The Imperial War Graves Commission had been established by Royal Charter in 1917. [1] Following the cessation of hostilities in 1918 at the end of the First World War, the Commission continued developing its plans to commemorate the war dead of both the British Army and troops from the Empire and its Dominions. The Commission had responsibility for war graves, but it was less clear who had responsibility for memorials. The Commission drew a distinction between individual commemoration of the dead and more general monuments such as battle exploits and regimental memorials. These latter were to be dealt with by a Battle Exploits Memorial Committee established in 1918 by the British Army's Adjutant-General. By 1919, a Cabinet-level desire for memorials to the army as a whole led to the establishment of the National Battlefield Memorials Committee, chaired by the Earl of Midleton. [2]

As plans progressed, it became apparent that the proposals for national battlefield memorials would overlap with those made by the Commission for memorials to the missing. In 1921, rather than fund two separate schemes, the responsibility for general war memorials was transferred from the National Battlefield Memorials Committee to the Imperial War Graves Commission. [3] [4] One of the proposals taken up from the Committee and acted upon by the Commission was the recommendation that commemorative tablets be "erected in French cathedrals which had particular associations with British troops during the war". [5] The Commission's committee to co-ordinate this consisted of Lieutenant General Sir George Macdonogh, Sir Herbert Creedy (Secretary to the War Office), the Commission's literary advisor Rudyard Kipling, and the Commission's founder and vice-chairman Fabian Ware. [6] The design was by Commission architect H. P. Cart de Lafontaine, with the tablets produced by sculptor Reginald Hallward. [6]

Cart de Lafontaine spoke fluent French, and in addition to designing the tablets he negotiated with the cathedral authorities. [7] The scheme was expanded to include cathedrals in Belgium as well. In some cases, the cathedrals had been badly damaged, and the placement of tablets was delayed until reconstruction had been completed. Other considerations included the placement of the tablet in the available space within the cathedrals, with some using a horizontal design instead of a vertical one. [8] The prototype tablet, produced for Amiens Cathedral, featured the Royal Coat of Arms and an inscription that referred to the armies of Great Britain and Ireland. [9]

All the later Commission tablets used a design that differed from the prototype tablet in that it brought together elements from all the dominions and India. [10] This standard design, following consultations with the College of Arms, had the Royal Coat of Arms surrounded by the shields of the coats of arms of the five Dominions: the Union of South Africa, the Commonwealth of Australia, the Dominion of New Zealand, Canada and the Dominion of Newfoundland. [7] The Indian Empire was represented by the insignia of the Order of the Star of India and its motto 'Heaven's light our guide'. Some designs of the tablet referred to 'The United Kingdom', while others referred to 'The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland'. The text within the main design includes the mottoes used in the Royal Coat of Arms: Honi soit qui mal y pense and Dieu et mon droit. The material used was gilded and coloured gesso set in a stone surround. [7] Other design elements included a banded laurel-like border with carved roses in each corner and one at bottom centre. [11] Some designs differed in the placement of the names of the dominions, and some varied in the colours used. The Westminster tablet is 5 feet 10 inches by 2 feet 10 inches (177.8 cm by 86.36 cm). [12] The Ypres tablet is 266 cm by 127 cm. [13]

- Dominion coats of arms

Locations and unveilings

The following table lists the known locations, unveiling dates and other details for the Commission's cathedral and church tablets in France, Belgium and other countries between 1923 and 1936.

Amiens Cathedral tablets

When the Commission took up the memorial tablet proposal from the National Battlefield Memorials Committee, several tablets had already been unveiled in Amiens Cathedral to the memory of Dominion forces that had participated in the Somme Offensive or in later battles in the area. Amiens is the capital of the département of the Somme, and the 13th-century Amiens Cathedral is the largest in Europe. This led to many requests after the war for permission to erect memorials there. Eleven such memorials are listed in The Middlebrook Guide to the Somme Battlefields, all located near the cathedral's south door. Six of them commemorate British or Dominion troops, including the prototype Commission tablet. [41] [42]

The first of these six memorials was erected for the Royal Canadian Dragoons and was dedicated on 12 April 1919 by the Archbishop of Amiens. [43] This was followed by a tablet to the Australian Imperial Force, unveiled on 7 November 1920 by Marshal Ferdinand Foch in the presence of the Australian High Commissioner Andrew Fisher. [44] The erection of a tablet to South African forces, reported in December 1920, had been suggested by the late Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa Louis Botha. [45] A tablet to the forces of Newfoundland was unveiled on 27 August 1922 by Sir Richard Squires the Prime Minister of Newfoundland. [46] The aforementioned prototype Commission tablet was unveiled on 9 July 1923 by Prince Arthur, the Duke of Connaught and wartime Governor-General of Canada. [14] The final tablet, to the soldiers of the New Zealand Division, was unveiled on 16 July 1923 by Lord Liverpool, wartime Governor (later Governor-General) of New Zealand, in the presence of the High Commissioner for New Zealand, Sir James Allen. [47]

| Tablet in Amiens | English [9] | French [9] |

|---|---|---|

|

A.M.D.G. IN SACRED MEMORY OF SIX HUNDRED THOUSAND MEN OF THE ARMIES OF GREAT BRITAIN & IRELAND WHO FELL IN FRANCE & BELGIUM DURING THE GREAT WAR 1914 – 1918 IN THIS DIOCESE LIE THEIR DEAD OF THE BATTLES OF THE SOMME 1916 THE DEFENCE OF AMIENS 1918 & THE MARCH TO VICTORY 1918 |

A LA MEMOIRE DES 600,000 SOLDATS DES ARMEES DE LA GND BRETAGNE & DE L'IRLANDE TOMBEES AU CHAMP D'HONNEUR EN FRANCE ET EN BELGIQUE 1914 – 1918 DANS CE DIOCESE REPOSENT LEURS MORTS DES BATAILLES DE LA SOMME 1916 DE LA DEFENSE D'AMIENS 1918 ET DE LA VICTOIRE 1918 |

The inscription uses the abbreviation A.M.D.G. for the Latin phrase Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam, and in addition to the Somme battles of 1916 refers to the defence of Amiens during the German spring offensive, and the Battle of Amiens and the Hundred Days Offensive that led to the Armistice in 1918. A version of the Amiens tablet is displayed at the headquarters of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in Maidenhead, UK. [9]

The form of the wording to be used on the tablets was the subject of correspondence between Commission officials and advisors. One such letter, between Kipling and Ware was written on 8 May 1923, with Kipling giving his thoughts on the wording proposed for the Notre Dame tablet (unveiled the following year) in light of the wording being used for the Amiens tablet (unveiled two months after this letter was written):

Of course, "diocese", in this connection, is absurd. It will have to be "France". Otherwise I don't see much wrong with the wording, except that, it seems to me, "dead", in place of "men", is the clou. The difficulty is the supplementary clause, and the word "especially", which, I fear, can't be avoided. I prefer "honoured" or "enduring" to "sacred", but there may be good reason for keeping to the last. I think that the word "here" after "rest", gives a touch of intimacy between the two lands.

Kipling went on to suggest a draft form of the inscription that was eventually used (with further changes) on the Notre Dame tablet. [48]

- Amiens memorial tablets

Tablets in France

The first standard tablet to be unveiled in France was that erected in Notre Dame de Paris. It was unveiled on 7 July 1924 by the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VIII) in his role as President of the Imperial War Graves Commission. French dignitaries present included the French President Gaston Doumergue, French Minister for War Charles Nollet, Military Governor of Paris Henri Gouraud, and generals Castelnau and Mangin. The tablet was shrouded in a Union flag, and following the unveiling the Prince handed a message to the President of France from King George V. [15]

| Tablet in Paris | English [49] | French [49] |

|---|---|---|

|

TO THE GLORY OF GOD AND TO THE MEMORY OF ONE MILLION DEAD OF THE BRITISH EMPIRE WHO FELL IN THE GREAT WAR 1914 – 1918 AND OF WHOM THE GREATER PART REST IN FRANCE |

A LA GLOIRE DE DIEU ET A LA MEMOIRE DU MILLION DE MORTS DE L'EMPIRE BRITANNIQUE TOMBES DANS LA GRANDE GUERRE 1914 – 1918 ET QUI POUR LA PLUPART REPOSENT EN FRANCE |

A succession of tablets of the same or similar design to the one erected in Paris were unveiled in French cathedrals, the majority in 1925, 1926 and 1927. One of those reported on at greater length in The Times was the service and ceremony for the tablet placed in Rouen Cathedral on the north wall of the chapel to Joan of Arc. This tablet, shrouded by a Union flag but framed in bronze rather than marble, was unveiled on 25 February 1925 by General Nevil Macready representing the Imperial War Graves Commission. The address by the Archbishop of Rouen spoke of the historical connections between Normandy and England, and Macready's unveiling speech in French concluded: "Glory to Joan of Arc! Glory to our dead!" Wreaths were laid under the Empire tablet and also at the memorial elsewhere in the cathedral to those of Rouen who fell in the war. [17]

The tablet at Arras Cathedral, the latest to be erected, was unveiled on 10 May 1936 by the Secretary of State for War Duff Cooper, present in his role as Chairman of the Imperial War Graves Commission. The erection of this tablet had been delayed by the restoration of the cathedral, which had been completed a few months earlier. Those present at this unveiling included representatives of Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Australia and India, together with the British ambassador to France George Clerk, Admiral Sir Morgan Singer, Lieutenant-General Sir George Macdonogh, and Commission architect Sir Reginald Blomfield. The French government was represented by Minister of Pensions René Besse, with General Schweissgut representing the French Minister of War. The Vicar-General represented the Bishop of Arras. Addresses were made by Duff Cooper, the Vicar-General and Fabian Ware. [40] Duff Cooper, as Macready had at Rouen 11 years earlier, made reference to Joan of Arc, going on to state that the Commission had laid wreaths in the chapel of Notre Dame de Lorette at the stained glass memorials of St Joan of Arc and St George, erected there by the Commission. [50]

A version of the standard French tablet is displayed at the headquarters of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in Maidenhead, UK. [49]

- Other French memorial tablets

-

Le Mans

-

Meaux

-

Nancy

-

Nantes

-

Senlis

-

Beauvais

-

Béthune

-

Orléans

Tablets in Belgium

The first tablets to be unveiled by the Commission in Belgium were at Mons and Mechelen, on Armistice Day in November 1926 and in March 1927. These were followed by the unveiling of the tablet in Brussels at the Cathedral of St Michael and St Gudula on 22 July 1927. This was two days before the unveiling of the Menin Gate in Ypres, one of the Commission's main memorials to the missing. The Menin Gate was unveiled by Lord Plumer, while Earl Haig was asked to unveil the Brussels tablet to the Empire's dead. Those present at the Brussels ceremony included the Belgian Prime Minister Henri Jaspar, the Belgian Minister of Justice Paul Hymans, the Minister of National Defence Charles de Broqueville (Belgian Prime Minister during the war), and the heir to the Belgian throne and future Leopold III, the Prince of Brabant. The British dignitaries accompanying Earl Haig included the British ambassador to Belgium George Dixon Grahame, British generals Hubert Gough and George Macdonogh, and the Commission's vice-chairman Fabian Ware. At the reception at the town hall following the unveiling, Haig delivered a speech in French, reported in The Times, paying tribute to the Empire's dead and to the resistance by the Belgian forces at the Battle of Liège to the invading German armies. [29] A further two tablets were unveiled in Belgium, at Antwerp in 1928 and at Ypres in 1931, the latter delayed by the rebuilding of St Martin's Cathedral.

| Tablet in Brussels | English [13] | Latin [13] |

|---|---|---|

|

TO THE GLORY OF GOD AND TO THE MEMORY OF ONE MILLION DEAD OF THE BRITISH EMPIRE WHO FELL IN THE GREAT WAR 1914 – 1918 MANY OF WHOM REST IN BELGIUM |

AD MAIOREM DEI GLORIAM ET IN MEMORIAM MILLIENS MILLIUM NOSTRORUM QUI EX IMPERIO BRITANNICO UNDIQUE COORTI ANNO DOMINI MCMXIV – MCMXVIII IN BELLO PRÆTER OMNIA MEMORANDO VITAM PRO PATRIA PROFUDERUNT QUORUM PARS MAGNA IN TERRA BELGICA DORMIUNT HOC MONUMENTUM EXSTRUXERE TOTIUS IMPERII GENTES ATQUE COMMUNITATES |

The inscriptions on the tablets in Belgium are in English and Latin, a decision that was taken in consultation with the Belgian ecclesiastical authorities, with Latin used as an alternative to the two official languages of the country. [51] The Latin text is not a direct translation of the English text, with the Latin wording discussed in correspondence in 1925 between Fabian Ware and Sir M. Sadler. [52]

Westminster Abbey tablet

The tablet produced for Westminster Abbey was similar in design to those erected in Belgium and France, but with a different inscription. The unveiling on 19 October 1926 was attended by the Prime Ministers of the Dominions, who were present in London for the Imperial Conference of 1926. The tablet, shrouded in a Union flag, was displayed in the nave of the Abbey, on a platform on the west side of the choir arch. The report in The Times stated that it was placed on a "specially designed screen covered with a fine brocade of blue, gold, and silver." A large number of dignitaries were present, while the public was limited to the available space remaining in the nave. Present were members of the British Cabinet, members of the Imperial War Graves Commission, Army, Navy and Air Force officers and commanders, representatives of associations such as the British Legion, the Red Cross and St Dunstan's, along with many Dominion representatives. In the front row were veterans who had been blinded during the war. [11]

Following protocol, the Prince of Wales arrived last and was received at the West Door of the Abbey by the Dean of Westminster William Foxley Norris, the Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, the Secretary of State for India Lord Birkenhead, the Secretary of State for the Colonies and for Dominion Affairs Leo Amery, the Secretary of State for War and Chairman of the Imperial War Graves Commission Sir Laming Worthington-Evans, Prime Minister of Newfoundland Walter Stanley Monroe, Prime Minister of New Zealand Gordon Coates, Prime Minister of Australia Stanley Bruce, Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa J. B. M. Hertzog, and Prime Minister of Canada William Lyon Mackenzie King. The Prince, in addition to representing the King, was present as President of the Imperial War Graves Commission. Like other members of the military, he wore morning dress rather than uniform. [11]

Following a short service by the Dean, the Prince of Wales, who himself had served in the war, declared:

I unveil this tablet in honour of our comrades, from every land under the Crown, who fell in the Great War. Time cannot dim our remembrance of them, nor lessen our gratitude to our Allies, who have given us the land in which many of them lie buried, so that we can care for their graves for ever.

This was followed by the laying of a wreath, the dedication by the Dean, the hymn O Valiant Hearts (a war poem set to music to remember the fallen of the Great War), prayers, the first verse of the National Anthem, and the closing blessing. After the Prince and the Prime Ministers had left, the Abbey was opened to allow those waiting outside to join the rest of the congregation in viewing the memorial. [11]

| Replica of Westminster tablet | Original [53] | Post-Second World War |

|---|---|---|

|

TO THE GLORY OF GOD AND TO THE MEMORY OF ONE MILLION DEAD OF THE BRITISH EMPIRE WHO FELL IN THE GREAT WAR 1914 – 1918 THEY DIED IN EVERY QUARTER OF THE EARTH AND ON ALL ITS SEAS AND THEIR GRAVES ARE MADE SURE TO THEM BY THEIR KIN THE MAIN HOST LIE BURIED IN THE LANDS OF OUR ALLIES OF THE WAR WHO HAVE SET ASIDE THEIR RESTING PLACES IN HONOUR FOR EVER |

TO THE GLORY OF GOD AND TO THE MEMORY OF THE DEAD OF THE BRITISH EMPIRE WHO FELL IN THE TWO WARS 1914 AND 1939 THEY DIED IN EVERY QUARTER OF THE EARTH AND ON ALL ITS SEAS AND THEIR GRAVES ARE MADE SURE TO THEM BY THEIR KIN THE MAIN HOST LIE BURIED IN THE LANDS OF OUR ALLIES WHO HAVE SET ASIDE THEIR RESTING PLACES IN HONOUR FOR EVER |

The Westminster tablet, originally unveiled in the nave, was later placed on the west wall of the Chapel of the Holy Cross. Located to the south of the West Door, this chapel was intended to be dedicated to those that fell in the war. [11] Sometimes referred to as the Warrior's Chapel, and located close to the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior, it was dedicated in 1932 as St George's Chapel. An inscription below the Empire memorial tablet states that the chapel was completed as a memorial to Field Marshal Lord Plumer. The following year, on Friday 10 November 1933, an annual tradition was started whereby a wreath of flowers from Commission cemeteries in Belgium and France was laid at the base of the tablet by Commission gardeners. [54]

Writing in 1937 in his report on the 20-year anniversary of the founding of the Commission, Ware stated that the tablets were erected "that the total losses of the British Empire might thus be visibly recorded". [55] Similar sentiments had been expressed in a lecture given in 1930 by H. C. Osborne, the Commission's representative in Canada, stating that the memorial tablets "will serve as perpetual and significant reminders, to all who read, of the part taken by our Empire in the greatest war in history." [56] Central to this, and to Ware's life's work establishing and building up the Commission, were the ideals of Empire and the imperial basis for the commemorations. [57] In his 1937 report, also published in book form, Ware declared:

These cathedral tablets are the first and only memorials to express in sculptured form the union of the partner nations in the British Commonwealth under one Crown. They have been called the coping-stone of the Commission's work. [58]

The wording on the Westminster tablet was changed following the Second World War to include those who fell in that war (the wordings on the Commission's tablets erected in Belgium and France were left unchanged). A further inscription below the tablet in St George's Chapel in the Abbey commemorates Ware himself, who died in 1949. [54] A print of the original tablet is held at the Abbey. [53]

Replicas and later history

Following the unveiling of the tablet in Westminster Abbey in 1926, requests were made to the Commission for permission to install replicas of the tablet in various locations. In some cases, full-scale copies were produced and installed in churches. [34] [59] In other cases, colour prints of the tablets were distributed to British Legion branches and other ex-servicemen organisations in the UK and abroad. [60] An example of the latter is the framed colour print recorded in the UK National Inventory of War Memorials as being held at a Royal British Legion branch in Liverpool, UK. [61] A similar print was presented by the Imperial War Graves Commission in 1935 to the Legacy Club in Fremantle, Australia, later presented to the city council for safekeeping. [62] A replica of the standard French tablet is installed at the museum (inaugurated in 1986) at the Delville Wood Memorial. [63]

Two replicas of the Westminster tablet are maintained by the Canadian Agency of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. These replicas are located in the Church of the Ascension, Hamilton, Ontario, and in Christ Church Cathedral, Vancouver, British Columbia. [64] [65] The Hamilton tablet, erected by the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry, was unveiled on 2 October 1927 by the former Lieutenant Governor of Ontario, Major General Sir John Morison Gibson. [66] As at the Westminster Abbey service the previous year, the hymn O Valiant Hearts was included in the service. Major General Sydney Chilton Mewburn addressed the congregation before the unveiling, and the memorial tablet was dedicated by the Lord Bishop of Niagara Derwyn Owen. [66] The tablet at Christ Church in Vancouver was agreed after lengthy correspondence between the Commission and the rector, the Reverend Dr Robert John Renison. [37] It was unveiled on the tenth anniversary of the Armistice (11 November 1928) by the Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia Robert Randolph Bruce. [67] A replica of the Westminster tablet was also installed in the Anglican Church of St George in Baghdad, Iraq, in the 1930s. [34]

As with the original tablets, those maintaining the replicas had to make a decision after the Second World War whether to leave the wording of the inscription unchanged, or to update the wording. The tablet in Vancouver was updated to include the Second World War period from 1939 to 1945, and then again to include the Korean War period from 1950 to 1953.

Over the years since their installation, a number of the Commission's tablets in France and Belgium have required maintenance, restoration or replacement. Some were affected by damp (at Orléans and Laon), [68] and some were damaged during the Second World War (at Rouen, Boulogne and Nantes). The replacement tablets were produced by Reginald Hallward's daughter Patricia Hallward. [69] Another tablet to suffer war damage is the one that was installed in St George's Anglican Church in Baghdad, Iraq. The current church building was erected by the British in 1936 during the period when they controlled the area after the First World War. Worship resumed at the church in 1998 following a 14-year period of neglect. [70] The stained glass windows, and the building itself, were memorials to the British regiments that fought Ottoman forces here in what was then Mesopotamia. Prior to the war in Iraq in 2003, the memorial tablet was faded but undamaged. [71] During the war, the tablet, mounted on the wall of the nave, was damaged by shrapnel. As reported by journalist Robert Fisk in December 2003 and April 2012, parts of the inscription were damaged, with the initial lines and final lines still legible: "... in honour for ever". [72] [73]

Notes and references

- Transcriptions

-

^ Canadian tablet: TO THE GLORY OF GOD

AND IN MEMORY

OF THE OFFICERS

NON-COMMISSIONED OFFICERS

AND MEN

OF THE ROYAL CANADIAN DRAGOONS

WHO GAVE UP THEIR LIVES

FOR THE CAUSE OF RIGHT AND LIBERTY

DURING THE GREAT WAR

1915 – 1916 – 1917 – 1918

ERECTED BY THEIR COMRADES

IN THE REGIMENT

A LA GLOIRE DE DIEU

ET À LA MÉMOIRE

DES OFFICIERS SOUS-OFFICIERS ET SOLDATS

DU ROYAL CANADIAN DRAGOONS

QUI ONT DONNÉ LEUR VIE

POUR LA CAUSE DU DROIT ET DE LA LIBERTÉ

DANS LA GRANDE GUERRE

1915 – 1916 – 1917 – 1918

ÉRIGÉ PAR LEURS CAMARADES

DU RÉGIMENT -

^ South African tablet: AVE ATQUE VALE

HOMMAGE DU PEUPLE RECONNAISSANT DU SUD-AFRIQUE A LA CHERE MÉMOIRE DES SUD-AFRICAINS TOMBÉS PENDANT LA GUERRE POUR LE DROIT 1914–1918

TO THE LOVING MEMORY OF THE SOUTH AFRICANS WHO FELL IN THE WAR FOR FREEDOM 1914–1918 THIS TABLET IS DEDICATED BY THE GRATEFUL PEOPLE OF SOUTH AFRICA

[Afrikaans inscription] -

^ New Zealand tablet: TO THE GLORY OF GOD

AND IN MEMORY OF THOSE

OF THE

NEW ZEALAND DIVISION

WHO FELL IN THE

BATTLES OF THE SOMME

AND

IN THE

FINAL DELIVERANCE

OF THIS CITY

A LA GLOIRE DE DIEU

ET

EN MEMOIRE

DE CEUX DE LA DIVISION

DE NOUVELLE ZÉLANDE

QUI SONT TOMBES DANS

LES BATAILLES DE LA SOMME

ET DANS LA

DELIVERANCE FINALE

DE CETTE VILLE -

^ Newfoundland tablet: To the glory of God,

to the honour of the Island,

and to the enduring memory

of those of the Newfoundland

Contingent who fell in the

first battle of the Somme.

"Behold, this stone shall be

a witness unto us."

Joshua 24–27A la gloire de Dieu,

à l'honneur de

l'Île de Terre-Neuve

et à l'ineffacable souvenir

des combattants de cette île

qui sont tombés dans la

première bataille de la Somme.

"Cette pierre sera témoin

pour vous."

Josué 24–27

-

^ Australian tablet: TO THE GLORY OF GOD

AND TO THE MEMORY OF

THE SOLDIERS OF

THE AUSTRALIAN IMPERIAL FORCE

WHO VALIANTLY PARTICIPATED IN THE

VICTORIOUS DEFENCE OF AMIENS

FROM MARCH TO AUGUST 1918

AND GAVE THEIR LIVES FOR THE CAUSE

OF JUSTICE, LIBERTY AND HUMANITY

THIS TABLET IS CONSECRATED BY

THE GOVERNMENT OF THE

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA.

À LA GLOIRE DE DIEU

ET À LA MÉMOIRE

DES SOLDATS DE

L'ARMÉE IMPERIALE AUSTRALIENNE

QUI PARTICIPÈRENT VAILLAMMENT

À LA DÉFENSE VICTORIEUSE D'AMIENS

DE MARS À AOÛT 1918

ET DONNERENT LEUR VIE POUR LA CAUSE

DE LA LIBERTÉ ET DE L'HUMANITÉ

CETTE PLAQUE EST CONSACRÉE PAR

LE GOUVERNEMENT FÉDÉRAL DE LA

CONFEDÉRATION AUSTRALIENNE

- Notes

- ^ Longworth 2003, p. 27.

- ^ Longworth 2003, p. 86.

- ^ Longworth 2003, p. 90.

- ^ Crane 2013, pp. 190–193.

- ^ Longworth 2003, p. 88.

- ^ a b CWGC 'Tablets in Cathedrals', p. 215.

- ^ a b c Longworth 2003, p. 99.

- ^ CWGC 'Tablets in Cathedrals', pp. 221–222.

- ^ a b c d "Soldiers of Great Britain and Ireland". IWM's War Memorials Archive. Imperial War Museums. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ Gibson & Kingsley Ward 1989, p. 129.

- ^ a b c d e "The Million Dead: Westminster Abbey Tablet". The Times. No. 44407. London. 20 October 1926. p. 11.

- ^ "War Memorial Tablet in Westminster Abbey". The Glasgow Herald. 15 October 1926. p. 13.

- ^ a b c "Memorial plaque of the soldiers of the Commonwealth who fell on Belgian soil". The Great War in Flanders Field. westhoek.be. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ a b "Amiens Memorial". The Times. No. 43389. London. 10 July 1923. p. 13.

- ^ a b "The Prince at Notre Dame". The Times. No. 43698. London. 8 July 1924. p. 13.

- ^ "British War Memorial at Le Mans". The Times. No. 43872. London. 29 January 1925. p. 11.

- ^ a b "Rouen War Memorial". The Times. No. 43896. London. 26 February 1925. p. 14.

- ^ "News in Brief: British War Memorial at Orleans". The Times. No. 44022. London. 24 July 1925. p. 13.

- ^ "Sir William Birdwood at Marseilles". The Times. No. 44023. London. 25 July 1925. p. 14.

- ^ a b c "News in Brief: British War Memorials in France". The Times. No. 44059. London. 5 September 1925. p. 9.

- ^ "Million British Dead – French War Memorial". The Daily News. Perth. 12 November 1925. p. 2.

- ^ "British War Memorial at Bayeux". The Times. No. 44149. London. 19 December 1925. p. 11.

- ^ "The Million Dead". The Times. No. 44406. London. 19 October 1926. p. 14.

- ^ "Memorial at Mons – The Empire's Million Dead". The Advertiser. Adelaide. 13 November 1926. p. 16.

- ^ "British War Memorial at Malines". The Times. No. 44540. London. 26 March 1927. p. 6.

- ^ "News in Brief: British Memorial at Boulogne". The Times. No. 44547. London. 4 April 1927. p. 13.

- ^ "News in Brief: Senlis Memorial to British Dead". The Times. No. 44630. London. 11 July 1927. p. 13.

- ^ "British War Memorial at Laon". The Times. No. 44636. London. 18 July 1927. p. 13.

- ^ a b "A British War Memorial". The Times. No. 44641. London. 23 July 1927. p. 12.

- ^ "News in Brief: Telegrams in Brief". The Times. No. 44703. London. 4 October 1927. p. 13.

- ^ "News in Brief: Lille Memorial to British Dead". The Times. No. 44720. London. 24 October 1927. p. 11.

- ^ a b c d CWGC 'Tablets in Cathedrals', p. 222.

- ^ CWGC 'Tablets in Cathedrals', p. 223.

- ^ a b c CWGC 'Other British and Dominion Memorials in Theatres of War', p. 273.

- ^ "The Million British Dead". The Times. No. 44922. London. 18 June 1928. p. 16.

-

^ "News in Brief: War Memorial at St. Omer". The Times. No. 45005. London. 22 September 1928. p. 13.

"News in Brief: Telegrams in Brief". The Times. No. 45031. London. 23 October 1928. p. 15. - ^ a b Adams, Neale (1989). "A Cathedral in the heart of the city: 1919–1932". Living Stones: A Centennial History of Christ Church Cathedral. Christ Church Cathedral.

- ^ "British War Memorial at Noyon". The Times. No. 45643. London. 14 October 1930. p. 14.

- ^ "British War Memorial at Ypres". The Times. No. 45833. London. 27 May 1931. p. 14.

- ^ a b "The Million Dead of the Empire". The Times. No. 47371. London. 11 May 1936. p. 14.

- ^ Middlebrook & Middlebrook 2007, pp. 316–318.

- ^ a b c d e f Campbell 1961, pp. 130–133.

- ^ Hopkins, John Castell (1920). The Canadian Annual Review of Public Affairs. Canadian Review Company. p. 62.

- ^ "News in Brief: Memorial to Fallen Australians". The Times. No. 42562. London. 8 November 1920. p. 11.

- ^ "News in Brief: S. African Memorial at Amiens". The Times. No. 42585. London. 4 December 1920. p. 9.

- ^ "News in Brief: Newfoundland Memorial at Amiens". The Times. No. 43121. London. 28 August 1922. p. 7.

- ^ "Memorial To New Zealanders". The Times. No. 43395. London. 17 July 1923. p. 11.

- ^ Kipling 1990, pp. 141–142.

- ^ a b c "One Million Dead of the British Empire". IWM's War Memorials Archive. Imperial War Museums. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ "Memorial to 1,000,000 Empire Dead: Tablet Unveiled In Arras Cathedral". The Straits Times. Singapore. 24 May 1936. p. 10.

- ^ Ware 1937, p. 35.

- ^ CWGC 'Tablets in Cathedrals', p. 216.

- ^ a b "One Million Dead of the British Empire". IWM's War Memorials Archive. Imperial War Museums. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ a b Gibson & Kingsley Ward 1989, p. 91.

- ^ Ware 1937, p. 34.

- ^ Osborne, H.C. (September 1930). "British Cemeteries and Memorials of the Great War". AACS Proceedings of the 44th Annual Convention. Association of American Cemetery Superintendents. Published online by the International Cemetery, Cremation and Funeral Association. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ Crane 2013, pp. 233–241.

- ^ Ware 1937, p. 36.

- ^ CWGC 'National And Local Memorials in the Dominions And Colonies', p. 268.

- ^ CWGC 'Tablets in Cathedrals', pp. 227–228.

- ^ "One Million Dead". IWM's War Memorials Archive. Imperial War Museums. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ "Tablet of Remembrance – Ceremony at Fremantle". The West Australian. Perth. 29 November 1935. p. 33.

- ^ "The Museum – The Entrance". Delville Wood Museum. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ "Canadian Agency, Commonwealth War Graves Commission: Works – Cathedral Tablets". Canadian Agency, Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ^ "Commonwealth War Graves Commission – Cathedral Tablets". Veterans Affairs Canada. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ a b Unveiling of memorial tablet to one million dead of the British Empire who fell in the Great War, 1914–1918, by Major General Sir J.M. Gibson, K.C.M.G. Robert Duncan & Company. 1927.

- ^ Archive item PAM 1928-4: "Unveiling of the memorial tablet to the one million dead of the British Empire who fell in the Great War, 1914–1918 by His Honour R. Randolph Bruce, Lieutenant-Governor of British Columbia". City of Vancouver Archives. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ CWGC 'Tablets in Cathedrals', p. 221.

- ^ CWGC 'Tablets in Cathedrals', pp. 216–217, 220, 223.

- ^ "History of St George's". The Foundation for Relief and Reconciliation in the Middle East. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ Blair, David (2 May 2002). "Iraq's Catholics strike a bargain". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^ Fisk, Robert (26 December 2003). "Deaths mount on both sides on Christmas Day in Iraq". The Independent. London.

- ^ Fisk, Robert (7 April 2012). "Under siege but vicar of Baghdad is still spreading the word". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 12 May 2022.

- References

-

Archive Catalogue Part 1 Sections 09-10 (PDF). Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

Section 9. Memorials Erected by the Commission; Section 10. Memorials Erected By Other Groups Or Individuals.- "Section 9F: Tablets in Cathedrals". Archive Catalogue Part 1 Sections 09-10. pp. 215–230.

- "Section 10E: National And Local Memorials in the Dominions And Colonies". Archive Catalogue Part 1 Sections 09-10. pp. 267–269.

- "Section 10F: Other British and Dominion Memorials in Theatres of War". Archive Catalogue Part 1 Sections 09-10. pp. 271–274.

- Campbell, Jacques (1961). Au Berceau de la Monarchie Anglaise (Les Souvenirs Britanniques en France). Coutances: P. Bellée.

- Crane, David (2013). Empires of the Dead: How One Man's Vision Led to the Creation of WWI's War Graves. London: William Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-745665-9.

- Gibson, T. A. Edwin; Kingsley Ward, G. (1989). Courage Remembered: The Story Behind the Construction and Maintenance of the Commonwealth's Military Cemeteries and Memorials of the Wars of 1914–18 and 1939–45. London: Stationery Office Books. ISBN 0-11-772608-7.

- Kipling, Rudyard (1990). Pinney, Thomas (ed.). The Letters of Rudyard Kipling: 1920–30. University of Iowa Press. ISBN 9780877458982.

- Longworth, Philip (2003) [1st. pub. CWGC:1967]. The Unending Vigil: The History of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (1985 revised ed.). Pen and Sword. ISBN 1-84415-004-6.

- Middlebrook, Martin; Middlebrook, Mary (2007). The Middlebrook Guide to the Somme Battlefields. Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-184415533-0.

- Ware, Fabian (1937). The Immortal Heritage: An Account of the Work and Policy of the Imperial War Graves Commission During Twenty Years 1917–1937. Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Photographs of memorial tablets

- Amiens (Australians on the Western Front 1914–1918); Nantes (La Cathédrale de Nantes); Béthune, Arras (Mémoires de pierre en Pas-de-Calais – Monuments aux morts du Pas-de-Calais); Amiens, Bayeux, Beauvais, Boulogne, Laon, Meaux, Nancy, Nantes, Notre Dame de Paris, Noyon, Orléans, Saint-Omer, Soissons, Reims (MémorialGenWeb); Church of the Ascension, Hamilton, Ypres, Marseille, Le Mans (Flickr); Westminster Abbey (Australian War Memorial collections)

- Further reading

- The Builder, Volume 125, 1923, p. 170: "British War Memorial Tablet, Amiens Cathedral"

- Tijdschrift van de West-Vlaamse Gidsenkring Ieper-Poperinge-Westland, Wilfried Beele, Westland Gidsenkroniek, jaargang 2010, nr. 3

- De gedenkplaat voor de Britse oorlogsdoden in de Sint-Maartenskerk in Ieper, Roger Verbeke, Gidsenkroniek Westland, 1998, nr. 6, pp. 191–198.

- Zij, die vielen als helden, Mariette Jacobs (2 volumes, Brugge, 1996, Uitgave Provincie West-Vlaanderen)

- Nog eens de gedenkplaat voor de Britse oorlogsdoden in de Sint-Maartenskerk in Ieper (The Great War in Flanders Field)

- Gedenkplaat Commonwealth-doden Sint-Maartenskerk (Ieper – WOI) (Inventaris Onroerend Erfgoed)

- St Omer Cathedral, including details of the tablet unveiling (Mémoires de pierre en Pas-de-Calais – Monuments aux morts du Pas-de-Calais)

- Amiens Cathedral, includes details of memorial tablet (Australians on the Western Front 1914–1918)

![Canada [T 1][42]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/99/WWI_memorial_tablet_to_Canadian_forces_in_Amiens_Cathedral.JPG/135px-WWI_memorial_tablet_to_Canadian_forces_in_Amiens_Cathedral.JPG)

![South Africa [T 2][42]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/34/WWI_memorial_tablet_to_South_African_forces_in_Amiens_Cathedral.JPG/135px-WWI_memorial_tablet_to_South_African_forces_in_Amiens_Cathedral.JPG)

![New Zealand [T 3][42]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/98/WWI_memorial_tablet_to_New_Zealand_forces_in_Amiens_Cathedral.JPG/135px-WWI_memorial_tablet_to_New_Zealand_forces_in_Amiens_Cathedral.JPG)

![Newfoundland [T 4][42]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/72/WWI_memorial_tablet_to_Newfoundland_forces_in_Amiens_Cathedral.JPG/135px-WWI_memorial_tablet_to_Newfoundland_forces_in_Amiens_Cathedral.JPG)

![Australia [T 5][42]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/28/WWI_memorial_tablet_to_Australian_forces_in_Amiens_Cathedral.JPG/135px-WWI_memorial_tablet_to_Australian_forces_in_Amiens_Cathedral.JPG)