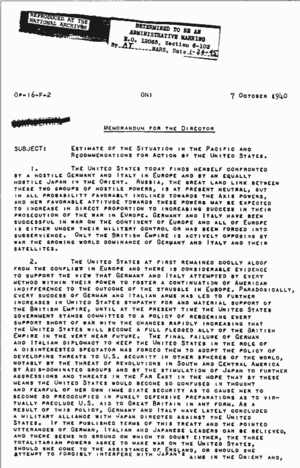

The McCollum memo, also known as the Eight Action Memo, was a memorandum, dated October 7, 1940, sent by Lieutenant Commander Arthur H. McCollum [1][ unreliable source?] in his capacity as director of the Office of Naval Intelligence's Far East Asia section. It was sent to Navy Captains Dudley Knox, who had reservations with the actions described within the memo, and Walter Stratton Anderson. Robert Stinnett asserts this memo was part of a conspiracy by the Roosevelt Administration to secretly provoke the Japanese to attack the United States in order to bring the United States into the European war without generating public contempt over broken political promises. Germany was not obliged to assist Japan if she attacked a third party, as the Tripartite Pact was defensive in nature, something overlooked by Stinnett. It was not until November 1941 that Germany had given Japan secret assurances outside of the treaty provisions. Stinnett has attributed to McCollum a position McCollum later expressly repudiated. [2] [3] U.S. military historian Conrad Crane rejected Stinnett's assertions as a distortion of the original document. [4]

The memorandum outlined the general situation of several nations in World War II and recommended an eight-part course of action for the United States to take in regard to the Japanese Empire in the South Pacific, suggesting the United States undertake a series of actions "that would serve as an effective check against Japanese encroachments in South-eastern Asia." The document also calls for war with Japan as a potential solution to contain it, but acknowledges that "It is not believed that in the present state of political opinion the United States government is capable of declaring war against Japan without more ado."

In July 1941, Japan moved to occupy the Southern half of French Indochina to sever supplies for the Chinese government, which induced a crippling oil embargo. The United States economic retaliation caused a crisis within the Japanese government, as Washington demanded a withdraw of Japanese troops in China in exchange for the revocation of the embargo. Moderates in Japan were willing to compromise, but this was quickly disrupted by militants, who decided on a course of war to address the economic crisis and seize these resources by force. While this might have induced the reaction McCollum had hoped for, the Japanese government demanded they be permitted to exert control over their occupied Chinese territories, something the United States was unwilling to accept. Evidence that Roosevelt ever saw the memorandum prior to these events is dubious at best, while the document itself could be interpreted as an offhand document without official U.S. government sanction. Roosevelt had expected an attack on British Malaya and the Dutch East Indies, but not Hawaii. [5] [6]

The Eight-Action plan

The McCollum memo contained an eight-part plan to counter rising Japanese power over East Asia, introduced with this short, explicit paragraph: [7]

- It is not believed that in the present state of political opinion the United States government is capable of declaring war against Japan without more ado; and it is barely possible that vigorous action on our part might lead the Japanese to modify their attitude. Therefore the following course of action is suggested:

- A. Make an arrangement with Britain for the use of British bases in the Pacific, particularly Singapore

- B. Make an arrangement with the Netherlands for the use of base facilities and acquisition of supplies in the Dutch East Indies

- C. Give all possible aid to the Chinese government of Chiang-Kai-Shek

- D. Send a division of long range heavy cruisers to the Orient, Philippines, or Singapore

- E. Send two divisions of submarines to the Orient

- F. Keep the main strength of the U.S. fleet now in the Pacific[,] in the vicinity of the Hawaiian Islands

- G. Insist that the Dutch refuse to grant Japanese demands for undue economic concessions, particularly oil

- H. Completely embargo all U.S. trade with Japan, in collaboration with a similar embargo imposed by the British Empire

- If by these means Japan could be led to commit an overt act of war, so much the better. At all events we must be fully prepared to accept the threat of war.

Reception of the Eight Actions

The memo was read and appended by Captain Knox, who wrote (pg. 6):

It is unquestionably to our interest that Britain be not licked – just now she has a stalemate and probably can't do better. We ought to make certain that she at least gets a stalemate. For this she will probably need from us substantial further destroyers and air-reinforcements to England. We should not precipitate anything in the Orient that would hamper our ability to do this – so long as probability continues. If England remains stable, Japan will be cautious in the Orient. Hence our assistance to England in the Atlantic is also protection to her and us in the Orient. However, I concur in your courses of action. We must be ready on both sides and probably strong enough to care for both.

This statement implies that, while the United States may have desired support to Britain, it did not warrant a reckless provocation might have impeded, in his analysis, the prosecution of a war with Germany. He did, however, regard American interests in the Far East as aligned with those of the British Empire.

The characterization of the McCollum memorandum as a recipe for war was not accepted by U. S. Army military historian [8] Conrad Crane, who wrote:

A close reading shows that its recommendations were supposed to deter and contain Japan, while better preparing the United States for a future conflict in the Pacific. There is an offhand remark that an overt Japanese act of war would make it easier to garner public support for actions against Japan, but the document's intent was not to ensure that event happened. [9]

See also

References

- ^ Stinnett, Robert. Day of Deceit. p. 7.

- ^ Young; McCollum, Arthur H., Rear Admiral. "The Calamitous 7th", The Saturday Review of Literature, 29 May 1954.

- ^ Pearl Harbor Investigations, Part 8, pp. 2447–3443.

- ^ "Dr. Conrad C. Crane".

- ^ La Feber, Walter. Polenberg, Richard The American Century, A History Of The United States Since the 1890s (John Wiley & Sons, Inc.), pp. 243-247.

- ^ Burns, James MacGregor (1970). Roosevelt: The Soldier of Freedom. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-15-178871-2.

- ^ U.S. Navy Code-Breakers, Linguists, and Intelligence Officers Against Japan 1910–1941, Captain Steven E. Maffeo, U.S.N.R., Ret., Rowman & Littlefield, 2016

- ^ "Dr. Conrad C. Crane".

- ^ Crane, Conrad (Spring 2001). "Book Reviews: Day of Deceit". Parameters. US Army War College.