Mata Sulakhni | |

|---|---|

ਮਾਤਾ ਸੁਲਖਨੀ | |

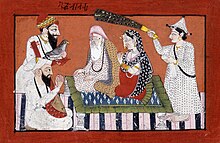

Sulakhni seated beside Guru Nanak in a circa 1780 painting from Mandi | |

| Personal | |

| Born | Ghummi Chona 1473 Pakhoke |

| Died | 1545 Kartarpur |

| Religion |

Hinduism (birth) Sikhism (convert) |

| Spouse | Guru Nanak |

| Children |

Sri Chand (born 1494) Lakhmi Das (born 1497) |

| Parent(s) | Mūl Chand Chona (father) Chando Rani (mother) |

Sulakhni (1473–1545), also known as Choni and often referred as Mata Sulakhni ("Mother Sulakhni"), was the wife of Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism. [1] [2] [3]

Name

In certain Janamsakhi traditions, such as the Merharban Wali Janamsakhi, Mata Sulakhni is known as Ghummi. [4] In the Bala Janamsakhi, her name is given as Sulakhni. [4] Surjit Singh Gandhi theorized that Gummi is a corrupted form of Choni, the name of her clan (Chona). [4] He further speculates that she was known as Ghummi in her birth house but went by the name Sulakhni at her in-laws house. [4] She is also known by the name of Kulamai. [5] According to Kahn Singh Nabha in his Mahan Kosh, only girls with super characteristics were given the name of Sulakhni. [3]

Biography

Family background

The father of Sulakhni was Mūl Chand, a Chona Khatri, whilst her mother was Chando Rani. [note 1] [1] [3] [6] Her father held a minor revenue office in the village of Pakkhoke Randhave (Pakhokhi village) in what is today the Gurdaspur district of the Punjab. [note 2] [1] She was born into a Hindu family in the village of Pakkhoke. [7]

Marriage

The marriage of Sulakhni to Nanak was arranged by Jai Ram, the brother-in-law of Nanak. [8] She was selected by Nanak's father partly due to her apparently "comely" appearance. [9] She was wedded to Guru Nanak on 24 September 1487. [1] [3] In that time period, it was custom for girls to be four to five years younger than the boy their marriage was arranged to. [3] Nanak would have been around eighteen years old at the time of their marriage. [3] The location the wedding itself occurred is disputed and given various locations amid Sikh sources but more likely took place in Batala. [note 3] [1] [4]

It is noted in Sikh lore that Mata Sulakhni's family had conflicts with Nanak, with an example of such regarding the manner of which the marriage ceremony would be performed. [6] Sulakhni's father, Mul Chand Chona, was unwavering about his desire to have a traditional marriage ceremony for his daughter and was opposed to Nanak's innovations. [6] He taunted Nanak to convince the Brahmins to agree to his proposals. [6] Whilst talking with the Brahmins, Nanak is said to have been seated beside an frail mud wall (kandh) on a rainy day, which was dangerous as the wall could have collapsed as a result. [6] Sulakhni warned Nanak through a courier about this but Nanak retorted that the wall will never fall down for centuries. [6] A surviving portion of the wall is believed to be preserved within the Kandh Sahib Gurdwara encased in a glass shield. [6] Nanak is said to have bested the Brahmins in the discourse and thus the marriage ceremony went along as per his design. [6]

When Nanak left for Sultanpur Lodhi for employment, Sulakhni remained at Talwandi until he earned enough and invited her to join him at Sultanpur in around the year 1488. [10] After she came to Sultanpur, her and her husband moved into a new house in the locality. [11]

Life as a mother

Sulakhni gave birth to two sons, Sri Chand, in 1494 and Lakhmi Das, in 1497. [note 4] [1] [4] According to Udasi lore, it is said she had an envisage of Shiva whilst giving birth to Sri Chand. [13] Her son, Sri Chand, would later go on to become a renowned spiritual leader himself. [1] [14] At some point, Nanak's father, Mehta Kalu, tried to tempt his son with the possibility of taking on a second wife but Nanak purportedly refused to entertain the idea as he thought Sulakhni was the most suitable wife for him, having been chosen by God to be his partner, and wanted to stay with her until death. [5] [15] She lived an ordinary life of a trading-class housewife at Sultanpur until the year 1499 or 1502, when her husband's religious preaching began after the River Bein episode. [16] [10] After one of Guru Nanak's udasis (travels), it is said he met-up with Sulakhni, their sons, and his father-in-law in Pakhokhi village. [17] Sulakhni had expressed her desire to accompany Nanak but remained at home to tend to and raise their sons. [18] She was reportedly a devouted wife and mother, who fully supported her husband's spiritual path and partook in it full-heatedly as a devotee herself. [19]

Kartarpur chapter

After the founding of Kartarpur by Nanak, Sulakhni moved there with him and was responsible for providing food and ensuring a comfortable stay for the visitors who came to see her husband and those who decided to remain there to live with him. [20] [19] Besides this, she also worked the farmland with her husband, was a cook, and served in the langar (community kitchen). [21] When Nanak chose Lehna as his successor rather than one of their sons, she was apparently displeased with the decision. [22] She survived her husband for a few years and died in 1545 at Kartarpur. [1]

Legacy

Nanak himself shared a close bond with his wife, which may have impacted his egalitarian and progressive views towards women. [23]

Amrita Pritam, a Punjabi poet, wrote the following poem about Sulakhni, specifically regarding her spiritual life as a wife of a religious man and raising of two sons alone when her husband was travelling: [24]

I was a shadow and am one still

I've travelled with the Sun on His course:

Have drunk of His glory

And bathed in a stream full of His light.

— Amrita Pritam (1989; 116–117), Introducing World Religions (2009) by Victoria Kennick Urubshurow, pages 436–437

Notes

- ^ Her mother is also referred to as 'Mata Chando'.

- ^ The name of the village is alternatively spelt as 'Pakkhoke Randhawa'.

- ^ The Bhai Bala Janamsakhi states the wedding took place in Sultanpur (which is unlikely as per Khatri marriage customs of the time). The Nanak Bans Prakash states the wedding took place in Talwandi. The Meharban Janamsakhi and Gyan Ratnavali states the wedding took place in Batala. [4]

- ^ Other sources give Sri Chand's birth date as 1491 and Lakhmi Das' as 1496. [12]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Singh, Harbans (2004). The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Vol. 4: S-Z (2nd ed.). Patiala: Punjabi University, Patiala. pp. 268–269. ISBN 0-8364-2883-8. OCLC 29703420.

- ^ Singh, Nikky-Guninder Kaur (2009). O'Brien, Joanne; Palmer, Martin (eds.). Sikhism. World Religions (3rd ed.). Infobase Publishing. pp. 120–121. ISBN 9781438117799.

- ^ a b c d e f Singh, Bhajan; Gill, M.K. (1992). "5. Mata Sulakhni". The Guru Consorts. Radha Publications. pp. 38–49. ISBN 9788185484112.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gandhi, Surjit Singh (2007). History of Sikh Gurus Retold: 1469-1606 C.E. History of Sikh Gurus Retold. Vol. 1. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. pp. 84, 195. ISBN 9788126908578.

- ^ a b Greenlees, Duncan (1960). The Gospel of the Guru-Granth Sahib. Theosophical Publishing House. pp. xxxvi, xlvi.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Singh, Bhupinder (October–December 2019). "Genealogy of Guru Nanak". Abstracts of Sikh Studies. 21 (4). Institute of Sikh Studies, Chandigarh.

-

^ Hawkins, John (2016). The Story of Religion: The rich history of the world's major faiths. Arcturus Publishing.

ISBN

9781784287368.

Sultanpur: When he was about 16 years old, Nanak left the village of Talwandi and set off for Sultanpur, a small town close to the Sutlej River. Nanak's married sister lived there and she helped her brother get a job as a tax collector for a local Muslim ruler. Over the next eight years, he combined his work with religious studies, and began to attract a group of followers. During this time, Nanak also married a Hindu girl, Sulakhni, and had two sons. Meanwhile, his fame was spreading. A large group of followers arrived in Sultanpur to join with Nanak in his hymns, prayers and contemplation.

-

^ Singh, Patwant (2007). The Sikhs. Crown Publishing Group.

ISBN

9780307429339.

An increasing number of men and women were beginning to gravitate towards him. In a rented house near his place of work, where he lived with two boyhood companions, people congregated for recitations, prayers and contemplation. To Nanaki, an ardent admirer of her gifted brother, this was, however, only one side of his life. The other side, she felt, was incomplete without a wife and children. And since Nanak too believed that "the secret of religion lay in living in the world without being overcome by it," he was persuaded. Through Jairam's initiative a match was arranged with Sulakhni, the daughter of a Kshatriya named Mulchand, from the village of Pakhoke near Batala, and Nanak was married at the age of nineteen.

- ^ Bal, Sarjit Singh (1969). Guru Nanak in the Eyes of Non-Sikhs. Publication Bureau, Panjab University. pp. x.

- ^

a

b Mandair, Arvind-Pal Singh (2022). Sikh Philosophy: Exploring gurmat Concepts in a Decolonizing World. Bloomsbury Introductions to World Philosophies. Bloomsbury Publishing.

ISBN

9781350202283.

Shortly after this episode Nanak left his ancestral village to find work at Sultanpur, where his brother-in-law procured a post for him as a village accountant. As Nanak began to earn his keep, he sent for his wife, Sulakhni, to join him. He was nineteen at the time. ... Twelve years passed in this way. Nanak and his wife settled into the comfortable life of the trading classes and had two sons. However, the regularity of this life was interrupted at around the age of thirty-three when Nanak failed to return from his morning ablutions near the river Bein. For three days no trace of Nanak could be found. The villagers believed that he had drowned. Then, on the fourth day Nanak reappeared as dramatically as he had disappeared, but his demeanour had changed. He had once again become silent and reclusive. When questioned about the state of his health, he responded with a perplexing statement: 'There is no Hindu; there is no Muslim', leading people to suspect he was possessed or had gone mad.

- ^ Dogra, R. C.; Mansukhani, Gobind Singh (1995). Encyclopaedia of Sikh Religion and Culture. Vikas Publishing House. p. 338. ISBN 9780706994995.

- ^ Journal of Comparative Sociology, Issues 4-5. Canada Sociological Research Centre. 1977. p. 34.

- ^ Ahuja, Jasbir Kaur (1995). "Udasi Sampradaya". Prabuddha Bharata: Or Awakened India. Vol. 100. Swami Smaranananda. pp. 933–935.

- ^ Singh, Prithi Pal (2006). The History of Sikh Gurus. Lotus Press. p. 6. ISBN 9788183820752.

- ^ The Panjab Past and Present. Vol. 3. Department of Punjab Historical Studies, Punjabi University. 1969. p. 288.

- ^ Jain, Pankaj (2017). Science and Socio-Religious Revolution in India: Moving the Mountains. Taylor & Francis. p. 69. ISBN 9781317690108.

- ^ Johar, Surinder Singh (1998). Holy Sikh Shrines. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. p. 61. ISBN 9788175330733.

- ^ Singh, Trilochan (1969). Guru Nanak - Founder of Sikhism: A Biography. Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee. p. 53.

- ^ a b Arneja, Simran Kaur. "Sikhism and Women". Ik Onkar One God. p. 95. ISBN 9788184650938.

-

^ Gill, Mahinder Kaur (2007). Guru Granth Sahib: The Literary Perspective. National Book Shop. p. 154.

ISBN

9788171164646.

Guru Nanak Dev came to Kartarpur and started the tradition of singing in the company of saints and Mata Sulakhni started looking after the arrangement of supplying food to people who stayed there.

- ^ Encyclopaedia of Social Work in India. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). Director, Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. 1987. p. 71.

- ^ Duggal, Kartar Singh (1987). Sikh Gurus: Their Lives and Teachings. Himalayan International Institute of Yoga Science and Philosophy of the U.S.A. pp. 68–69. ISBN 9780893891060.

- ^ Singh, Pashaura; Fenech, Louis E. (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 615. ISBN 9780191004117.

- ^ Urubshurow, Victoria Kennick (2009). Introducing World Religions. Journal of Buddhist Ethics. pp. 436–437. ISBN 9780980163308.