| Malkīkarib Yuha’min | |

|---|---|

| King of the Himyarite Kingdom | |

| Reign | 375–400 CE |

| Predecessor | Tharan Yuhanim |

| Successor | Abu Karib |

| Died |

c. 400 Yemen |

| Father | Tharan Yuhanim |

| Religion |

|

Malkīkarib Yuha’min (r. 375–400) was a king ( Tubba', Arabic: تُبَّع) of the Himyarite Kingdom (in modern-day Yemen), succeeding his father Tharan Yuhanim. Byzantine sources and contemporary historians credit him with converting the ruling class of the Himyarite Kingdom from paganism to Judaism (whereas later Islamic sources ascribe this event to Abu Karib, his son). These events are chronicled by the fifth-century Ecclessiastical History of the Anomean Philostorgius and the sixth-century Syriac Book of the Himyarites. Such sources implicate the motive for conversion as a wish on the part of the Himyarite rulers to distance themselves from the Byzantine Empire which had tried to convert them to Christianity. [1]

Malkikarib was likely at an advanced age when he took the throne as he immediately initiated a coregency with his children. [2] He first entered into a coregency with his son Abīkarib Asʿad (Abu Karib). Later in his reign, he entered into coregency with both his sons Abīkarib Asʿad and Dharaʾʾamar Ayman. According to two inscriptions, RES 3383, Ja 856 (= Fa 60), and Garb Bayt al-Shwal 1, Malkikarib Yuhamin constructed a mikrāb [3] named Barīk in the city of Marib (and also capital of the ancient Saba kingdom) in order to replace the polytheistic temple of the moon deity Almaqah. The term mikrāb refers to a structure that is either the equivalent of a synagogue [4] or refers to a local Himyarite variant of this Jewish institution. [5]

Very little memory remained of Malkikarib Yuhamin remained among traditionalist writers from the Islamic era. Al-Hamdani believed that he had reigned for thirty-five years and, besides this, only knew that he was the father of Abīkarib Asʿad. [4]

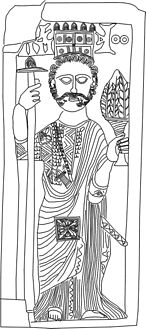

Iconography

The standing relief image of a crowned man, is taken to be a representation possibly of Malkīkarib Yuhaʾmin or more likely the Christian Esimiphaios (Samu Yafa'). [6]

Inscriptions mentioning Malkikarib Yuhamin

Ja 671 + 788

This inscription dates form 360 to 370, prior to Malkikarib taking the throne. It is carved on a stela from the Great Temple of the god Almaqah. It is the earliest inscription to mention the Marib Dam. [7]

[Sharah ˙ ʿathat Ashwaʿ and his] son 2 Mar[thadum] Asʾar banū Su[kh]3 aymum mas[ters of the pala]ce of Raymān, princes of the two commu4 nes Yarsum of *Samʿī, the third of *Haga5 r um, and Khawlān Gudādatān, have dedicated to their lo6 [rd] *Almaqahū *Thahwān master of *Awām 7 a bronze statue when order was given to him by his two lo8 rds Thaʾrān Yuhanʿim and his son Malkīka9 rib Yuʾmin, kings of Sabaʾ, of dhu-Raydān, of H ˙ a10d ˙ ramawt and of Yamnat, to take the lead of the army with the Arabs 11 when the Dam was breached at H ˙ abābid ˙ and *Rah ˙ bum, 12 and was breached the entire great wall which is between H ˙ abābid ˙ and 13 *Rah ˙ bum and, of the dam, were breached 70 *shawh ˙ a14t ˙ ; and they praised the power of their lord *Almaqah15ū-*Thahwān master of *Awām because He granted them 16 their fulfilment, with his order to retain for [t]17hem the flood until they completed their works; and he 18 praised their lord *Almaqahū Thahwān master 19 of *Awām because He granted them the oracles that to Him 20 had been demanded; and may He continue to grant them the fa21vour and the benevolence of their two lords Thaʾrān Yuhanʿim 22 and his son Malkīkarib Yuʾmin, kings 23 of Sabaʾ, of dhu-Raydān, of H ˙ ad ˙ ramōt, and of Yamnat; and they rep24aired this breach in three months, 25 during dhu-Sabaʾ, -*Ilʾilāt, and -*Abhī.

Bayt al-Ashwal 2

This inscription dates to January 384 and is carved on a relief from a large block, likely originating from Zafar, Yemen. It describes Malkikarib Yuhamin in coregency with his two sons and commemorating the construction of a new palace. This is also the first time where the rejection of polytheism is expressed in an extant inscription from the Himyarite kingdom. [8]

Malkīkarib Yuhaʾmin and his sons Abīkarib Asʿad and Dharaʾʾamar Ayman, kings of Sabaʾ, of dhu-Raydān, 2 of Hadramawt, and of Yamnat, have built, laid the foundations of, and completed the palace Kln3m, from its base to its summit, with the support of their lord, the Lord of the Sky4 in the month of dhu-diʾāwān {January} of the year four hundred and ninety-three.

Ja 856 = Fa 60.

This is the oldest inscription mentioning the construction of a mikrāb. It was found at Marib, which was once the capital of the ancient Saba kingdom. It likely dates to the first half of Malkikarib's reign, between 375 and 384. [9]

Malkīkarib Yuhaʾmin and his son [Abīkarib Asʿad, kings of] 2 Sabaʾ, of dhu Raydān, of H ˙ ad ˙ ramawt and [of Yamnat have built from the foundations to] 3 the summit their mikrāb Barīk for their salvation and [... ...]

Maʾsal 1 = Ry 509

This inscription dates to the first half of the fifth century and describes the conquest of Central Arabia and was carved on a desert ravine from that area. It mentions Malkikarib Yuhamin in the capacity of him being the father of the king who created the inscription, Abu Karib. [10]

Abīkarib Asʿad and his son H ˙ aśśān Yuhaʾmin, kings of Sabaʾ, 2 of dhu-Raydān, of H ˙ ad ˙ ramawt, and of Yamnat, and of the Arabs of the Upper-Country {Twḍ } and of the Coast {Thmt}, 3 son of H ˙ aśśān Malkīkarib Yuhaʾmin, king of Sabaʾ, of dhu-4 Raydān, of H ˙ ad ˙ ramawt, and of Yamnat, have had this inscription carved in the wād5 ī Maʾsal Gumh ˙ ān, when they came and took possession of the Land 6 of Maʿaddum during the installation of garrisons provided by some of their communes, with their commune 7 H ˙ ad ˙ ramawt and Sabaʾ—the sons of Marib—the junior offspring 8 of their princes, the youngest of their officers, their ag9 ents, their huntsmen, and their troops, as well as their Arabs,10 Kiddat, Saʿd, ʿUlah, and H[...]

See also

References

Citations

- ^ Hughes 2020, p. 26–29.

- ^ Robin 2012, p. 264–265.

- ^ Grasso 2023, p. 79.

- ^ a b Robin 2012, p. 265–266.

- ^ Robin 2021, p. 297–303.

- ^ Yule, Paul, A Late Antique christian king from Ẓafār, southern Arabia, Antiquity 87, 2013, 1124-35.

- ^ Robin 2015, p. 108–109.

- ^ Robin 2015, p. 133–134.

- ^ Robin 2015, p. 136.

- ^ Robin 2015, p. 144–145.

Sources

- Grasso, Valentina (2023). Pre-Islamic Arabia: Societies, Politics, Cults and Identities During Late Antiquity.

- Hughes, Aaron (2020). "South Arabian 'Judaism', Ḥimyarite Raḥmanism, and the Origins of Islam". In Segovia, Carlos Andrés (ed.). Remapping emergent Islam: texts, social settings, and ideological trajectories. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 15–42.

- Robin, Christian Julien (2012). "Arabia and Ethiopia". In Johnson, Scott Fitzgerald (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press. pp. 247–332.

- Robin, Christian Julien (2015). "Before Ḥimyar: Epigraphic Evidence for the Kingdoms of South Arabia". In Fisher, Greg (ed.). Arabs and Empires Before Islam. Oxford University Press. pp. 90–126.

- Robin, Christian Julien (2021). "Judaism in Pre-Islamic Arabia". In Ackerman-Lieberman, Phillip Isaac (ed.). The Cambridge History of Judaism. Cambridge University Press. pp. 294–331.