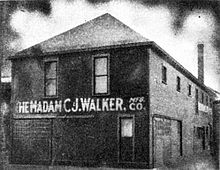

Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company, Indianapolis, Indiana, 1911. | |

| Company type | Private |

|---|---|

| Industry | Hair products |

| Founded | 1910 |

| Founder | Madam C. J. Walker |

| Defunct | 1981 |

| Headquarters | Indianapolis, Indiana, United States |

| Products | Cosmetics |

The Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company (Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Co., The Walker Company) was a cosmetics manufacturer incorporated in Indianapolis, Indiana in 1910 by Madam C. J. Walker. It was best known for its African-American cosmetics and hair care products, and considered the most widely known and financially successful African-American-owned business of the early twentieth century. [1] The Walker Company ceased operations in July 1981. [2]

History

Early Life

Madam C.J. Walker, born Sarah Breedlove was born on December 23, 1867, in Delta, LA. Born to formerly enslaved parents, she was an orphan by the time she was seven years old. In 1881 she married Moses McWilliams at the age of 14. The couple welcomed a baby girl in 1885, named Lelia. Two years after the birth of their daughter, her husband passed away. [3]

1905-1910

Madam C. J. Walker, then Sarah Breedlove, first formed the idea of her company in Denver, Colorado, in the early twentieth century. Like many women of her era, she suffered from scalp infections and hair loss because of hygiene practices, diet and products that damaged her hair. [4] Walker had initially learned about hair and scalp care from her brothers, who owned a barber shop in St. Louis during the 1880s and 1890s. Around 1904, Walker—still known as Sarah Breedlove McWilliams Davis (after marriages to Moses McWilliams and John Davis) became a sales agent for Annie Malone, an African-American businesswoman, who founded a company in 1900 manufacturing a "Wonderful Hair Grower." Before 1900, there were several other black women who called themselves "hair growers" and who advertised in black newspapers including the Baltimore Afro-American and the St. Louis Palladium. In 1900 Gilbert Harris spoke about "Work in Hair" at the National Negro Business League convention in Boston.

After moving to St. Louis, Missouri in 1889, she worked as a cook and as a laundress. [3] Edmund L. Scholtz, a wholesale druggist in Denver, assisted her in developing her own ointment to heal scalp disease. [5]

In January 1906, [5] she married Charles Joseph Walker and changed her name to Madam C. J. Walker. Together they marketed and sold "Walker's Wonderful Hair Grower." in Denver and surrounding Colorado communities. [4] The first advertisements for Walker's haircare products appeared in 1906 in The Statesman and featured a front and back image of her shoulder-length hair which boasted the growth was from only two years' treatment. [5]

In July 1906, Walker and her new husband left Denver to begin traveling throughout Texas, Oklahoma and several southern states to market their product line. In September 1906, her daughter Lelia took over the business operations in Denver. [4] By May 1907, tensions between Malone and Walker came to a head, and The Statesman reported that Walker would discontinue business in Denver altogether and planned to travel throughout the southern United States and eventually to northern states. [4]

As she gained popularity, it became clear that Walker would need a temporary headquarters for her business-- Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania was chosen for its convenient and accessible shipping arrangements. [4] In the midst of Pittsburgh's 1908 economic crisis, Walker opened a hair parlor at 2518 Wylie Avenue among a number of other black businesses. [4] Walker also began training her own sales agents and founded Lelia College, a school named after her daughter. [4] She placed Lelia in charge of these agents, while traveling west to Ohio. At twenty-three, Lelia was sent to Bluefield, West Virginia to survey untapped markets. [4]

1910–1981

In January 1910, Walker and her husband traveled to Louisville, Kentucky where she offered stock to Reverend Charles H. Parrish and Alice Kelly. The pair suggested that Walker write to Booker T. Washington for support of her company. She wrote to Washington, requesting his aid in raising $50,000 to form a stock company. Washington replied, "I hope very much you may be successful in organizing the stock company and that you may be successful in placing upon the market you preparation," but did not offer his assistance. [6]

Walker and her husband arrived in Indianapolis, Indiana on 10 February 1910. Seeking residence with Dr. Joseph Ward on Indiana Avenue, Indianapolis's African-American thoroughfare, Walker opened a salon in his home where she hosted sales agents and clients. Between February and April 1910, Walker grew her customer base. Multi-level marketing was Walker's most successful strategy. [4]

By August 1910, Walker had 950 sales agents and thousands of clients coming through the salon. With her client base growing, Walker sought out two Indianapolis lawyers, Freeman Ransom, and Robert Lee Brokenburr. In the summer of 1910, Walker asked Brokenburr to draft articles of incorporation for the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company of Indiana. The mission of the company was to, "sell a hairgrowing, beautifying, and scalp disease-curing preparation and clean scalps the same." [7] Walker, her husband, and daughter were named the sole members of the board of directors. [4]

In November, with funds from her mail order business and Ward residence salon, Walker purchased a brick home at 640 North West Street. By December Walker had added two more rooms and a bath with plans for the addition of a factory, laboratory, and salon. [8] According to Brokenburr's incorporation papers, the North West Street building was to be named the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company of Indiana. [8] In 1911 Madam C.J. Walker was listed as the sole stakeholder of the company.

Marjorie Joyner (1896-1994) became an agent for Walker. By 1919 Joyner was the national supervisor over Walker's 200 beauty schools. A major role was sending their hair stylists door-to-door, dressed in black skirts and white blouses with black satchels containing a range of beauty products that were applied in the customer's house. Joyner taught some 15,000 stylists over her fifty-year career. She was also a leader in developing new products, such as her permanent wave machine. She helped write the first cosmetology laws for the state of Illinois, and founded both a sorority and a national association for black beauticians. In 1987 the Smithsonian Institution in Washington opened an exhibit featuring Joyner's permanent wave machine and a replica of her original salon. [9]

After Walker's death in 1919 her daughter A'Lelia became president of the company. [10] During her tenure the company built a new headquarters and manufacturing plant in 1927 in Indianapolis. However the Great Depression hurt sales and forced her to sell personal art and antiques to keep the company operating. [11] When A'Lelia died in 1931 her adopted daughter Mae Walker succeeded her until her death in 1945. In turn Mae's daughter A'Lelia Mae Perry Bundles became the fourth company president. The company closed in 1981 but the 1927 building later became the Madam Walker Legacy Center. [12]

2016-present

In March 2020, Sundial Brands revived the brand name as Madam C. J. Walker Beauty Culture that is sold by Sephora. [13]

See also

References

- ^ "Black History Month: How Madam C.J. Walker pioneered success as the first self-made millionairess". Guinness World Records. 2021-02-16. Retrieved 2022-11-01.

- ^ "845 F. 2d 326 - Mohr v. R Bowen Md". openjurist.org. 1988. p. 326. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ^ a b Michals, Debra (2015). "Madam C.J. Walker(1867-1919)". National Women's History Museum. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bundles, A'Lelia (2001). On Her Own Ground : The Life and Times of Madam C.J. Walker. New York: Scribner. pp. 79–91. ISBN 0684825821.

- ^ a b c Bundles, A'Lelia (2001). On Her Own Ground : The Life and Times of Madam C.J. Walker. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0684825821.

- ^ Bundles, A'Lelia (2001). On her own ground : the life and times of Madam C.J. Walker. New York: Scribner. pp. 101. ISBN 0684825821.

- ^ Lewis, William M. (August 26, 1911). "The K. of P. Meeting". Indianapolis Freeman.

- ^ a b Bundles, A'Lelia (2001). On her own ground : the life and times of Madam C.J. Walker. New York: Scribner. pp. 105. ISBN 0684825821.

- ^ Jessie Carney Smith, ed., Encyclopedia of African American Popular Culture (2010) pp 435-38.

- ^ Jones, Alexis; Siclait, Aryelle (27 March 2020). "Who Was Madam C.J. Walker's Daughter A'Lelia And What Happened To Her?". Women'sHealthMag.com. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ "Remembering A'Lelia Walker, Who Made A Ritzy Space For Harlem's Queer Black Artists". NPR. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ Desta, Yohana (23 March 2020). "Self Made: What Happened to Madam C.J. Walker's Hair-Care Empire?". VanityFair.com. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ "Sephora teams up with iconic black hair brand". www.marketplace.org. 28 March 2016.

- Madam C. J. Walker

- Cosmetics companies of the United States

- Manufacturing companies based in Indianapolis

- Defunct companies based in Indianapolis

- 1910 establishments in Indiana

- 1981 disestablishments in Indiana

- American companies established in 1910

- Manufacturing companies disestablished in 1981

- Manufacturing companies established in 1910

- Black-owned companies of the United States

- History of women in Indiana