| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Lupron, Eligard, Lucrin, Lupaneta, others |

| Other names | leuprolide, leuprolidine, A-43818, Abbott-43818, DC-2-269, TAP-144 |

| AHFS/ Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a685040 |

| License data |

|

|

Pregnancy category |

|

|

Routes of administration | implant, subcutaneous, intramuscular |

| Drug class | GnRH analogue; GnRH agonist; Antigonadotropin |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Elimination half-life | 3 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard ( EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.161.466 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

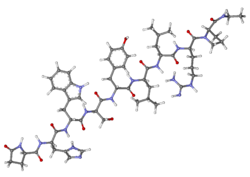

| Formula | C59H84N16O12 |

| Molar mass | 1209.421 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model ( JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Leuprorelin, also known as leuprolide, is a manufactured version of a hormone used to treat prostate cancer, breast cancer, endometriosis, uterine fibroids, as part of transgender hormone therapy, for early puberty, or to perform chemical castration of violent sex offenders. [10] [11] [12] It is given by injection into a muscle or under the skin. [10]

Leuprorelin is in the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogue family of medications. [10] It works by decreasing gonadotropins and therefore decreasing testosterone and estradiol. [10] Common side effects include hot flashes, unstable mood, trouble sleeping, headaches, and pain at the site of injection. [10] Other side effects may include high blood sugar, allergic reactions, and problems with the pituitary gland. [10] Use during pregnancy may harm foetal development. [10]

Leuprorelin was patented in 1973 and approved for medical use in the United States in 1985. [10] [13] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines. [11] It is sold under the brand name Lupron among others. [10]

Medical use

Leuprorelin may be used in the treatment of hormone-responsive cancers such as prostate cancer and breast cancer. It may also be used for estrogen-dependent conditions such as endometriosis [14] or uterine fibroids.

It may be used for precocious puberty in both males and females, [15] and to prevent premature ovulation in cycles of controlled ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization ( IVF). This use is controversial since the Lupron label advises against using the drug when one is considering pregnancy, due to a risk of birth defects. [16]

It may be used to reduce the risk of premature ovarian failure in women receiving cyclophosphamide for chemotherapy. [17]

Along with triptorelin and goserelin, it has been used to delay puberty in transgender youth until they are old enough to begin hormone replacement therapy. [18] Researchers have recommended puberty blockers after age 12, when the person has developed to Tanner stages 2–3, and then cross-sex hormones treatment at age 16. This use of the drug is off-label, however, not having been approved by the Food and Drug Administration and without data on long-term effects of this use.[ needs update] [19]

They are also sometimes used as alternatives to antiandrogens like spironolactone and cyproterone acetate for suppressing testosterone production in transgender women. [20] [21] [22] It also is used for suppressing estrogen production in transgender men. [23]

It is considered a possible treatment for paraphilias. [24] Leuprorelin has been tested as a treatment for reducing sexual urges in pedophiles and other cases of paraphilia. [25] [26]

Side effects

Common side effects of leuprorelin injection include redness/burning/stinging/pain/bruising at the injection site, hot flashes (flushing), increased sweating, night sweats, tiredness, headache, upset stomach, nausea, diarrhea, impotence, testicular shrinkage, [8] constipation, stomach pain, breast swelling or tenderness, acne, joint/muscle aches or pain, trouble sleeping (insomnia), reduced sexual interest, vaginal discomfort/dryness/itching/discharge, vaginal bleeding, swelling of the ankles/feet, increased urination at night, dizziness, breakthrough bleeding in a female child during the first two months of leuprorelin treatment, weakness, chills, clammy skin, skin redness, itching, or scaling, testicle pain, impotence, depression, or memory problems. [27] The rates of gynecomastia with leuprorelin have been found to range from 3 to 16%. [28]

A cohort of women that were prescribed leuprorelin to delay precocious puberty as children has developed osteoporosis and brittle teeth at an unexpected rate; However, the FDA has not established that these conditions were caused by leuprorelin. [29]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Leuprorelin is a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogue acting as an agonist at pituitary GnRH receptors. GnRH receptor agonists initially increase the secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) by the anterior pituitary and increased serum estradiol and testosterone levels via the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis (HPG axis). However, normal functioning of this axis requires pulsatile release of GnRH from the hypothalamus. Continuous exposure to an agonist such as leuprorelin for several weeks causes pituitary GnRH receptors to become desensitised and no longer responsive. This desensitisation is the objective of leuprorelin therapy because it ultimately reduces LH and FSH secretion, leading to hypogonadism and a dramatic reduction in estradiol and testosterone levels regardless of sex. [30] [31]

Available forms

Leuprorelin is available in the following forms, among others: [32] [33] [34] [35] [36]

- Short-acting daily intramuscular injection (Lupron) [4]

- Long-acting depot intramuscular injection (Lupron Depot) [8] [37] [38] [39]

- Long-acting depot subcutaneous injection (Eligard) [5]

- Long-acting subcutaneous injection (Fensolvi) [6]

- Long-acting subcutaneous implant (Viadur) [7]

- Long-acting leuprolide mesylate (Camcevi) for the treatment of advanced prostate cancer. [40]

- Leuprolide acetate and norethindrone acetate co-packaged pack (Lupaneta Pack) [41] [42]

Chemistry

The peptide sequence is Pyr-His-Trp-Ser-Tyr-D-Leu-Leu-Arg-Pro-NHEt (Pyr = L- pyroglutamyl).

History

Leuprorelin was discovered and first patented in 1973 and was introduced for medical use in 1985. [43] [44] It was initially marketed only for daily injection, but a depot injection formulation was introduced in 1989. [44]

Approvals

- Lupron injection was approved by the FDA for treatment of advanced prostate cancer on 9 April 1985. [45] [4] [43] [44]

- Lupron depot for monthly intramuscular injection was approved by the FDA for palliative treatment of advanced prostate cancer on 26 January 1989. [8]

- Viadur was approved by the FDA for palliative treatment of advanced prostate cancer on 6 March 2000. [7]

- Eligard was approved by the FDA for palliative treatment of advanced prostate cancer on 24 January 2002. [5]

- Fensolvi was approved by the FDA for children with central precocious puberty on 4 May 2020. [6] [46]

Society and culture

Legal status

On 24 March 2022, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) adopted a positive opinion, recommending the granting of a marketing authorization for the medicinal product Camcevi, intended for the treatment of the cancer of the prostate in adult men when the cancer is "hormone-dependent", which means that it responds to treatments that reduce the levels of the hormone testosterone. [47] The applicant for this medicinal product is Accord Healthcare S.L.U. [47] Leuprorelin was approved for medical use in the European Union in May 2022. [9] [48]

Names

Leuprorelin is the generic name of the drug and its INN and BAN, while leuprorelin acetate is its BANM and JAN, leuprolide acetate is its USAN and USP, leuprorelina is its DCIT, and leuproréline is its DCF. [49] [50] [51] [52] It is also known by its developmental code names A-43818, Abbott-43818, DC-2-269, and TAP-144. [49] [50] [51] [52]

Leuprorelin is marketed by Bayer AG under the brand name Viadur, [7] by Tolmar under the brand names Eligard and Fensolvi, [5] [6] and by TAP Pharmaceuticals (1985–2008), by Varian Darou Pajooh under the brand name Leupromer and Abbott Laboratories (2008–present) under the brand name Lupron.

Controversy

In October 2001, the US Department of Justice, states attorneys general, and TAP Pharmaceutical Products, a subsidiary of Abbott Laboratories, settled criminal and civil charges against TAP related to federal and state medicare fraud and illegal marketing of the drug leuprorelin. [53] TAP paid a total of $875 million, which was a record high at the time. [54] [55] The $875 million settlement broke down to $290 million for violating the Prescription Drug Marketing Act, $559.5 million to settle federal fraud charges for overcharging Medicare, and $25.5 million reimbursement to 50 states and Washington, D.C., for filing false claims with the states' Medicaid programs. [55] The case arose under the False Claims Act with claims filed by Douglas Durand, a former TAP vice president of sales, and Joseph Gerstein, a doctor at Tufts University's HMO practice. [54] Durand, Gerstein, and Tufts shared $95 million of the settlement. [54]

There have since been various suits concerning leuprorelin use, none successful. [56] [57] They either concern the oversubscription of the drug or undue warning about the side effects. Between 2010 and 2013, the FDA updated the Lupron drug label to include new safety information on the risk of thromboembolism, loss of bone density and convulsions. [58] The FDA then asserted that the benefits of leuprorelin outweigh its risks when used according to its approved labeling. Since 2017, the FDA has been evaluating leuprorelin's connection to pain and discomfort in musculoskeletal and connective tissue. [59]

"Lupron protocol"

A 2005 paper in the controversial and non- peer reviewed journal Medical Hypotheses suggested leuprorelin as a possible treatment for autism, [60] the hypothetical method of action being the now defunct hypothesis that autism is caused by mercury, with the additional unfounded assumption that mercury binds irreversibly to testosterone and therefore leuprorelin can help cure autism by lowering the testosterone levels and thereby mercury levels. [61] However, there is no scientifically valid or reliable research to show its effectiveness in treating autism. [62] This use has been termed the "Lupron protocol" [63] and Mark Geier, the proponent of the hypothesis, has frequently been barred from testifying in vaccine-autism related cases on the grounds of not being sufficiently expert in that particular issue [64] [65] [66] and has had his medical license revoked. [63] Medical experts have referred to Geier's claims as "junk science". [67]

Research

As of 2006 [update], leuprorelin was under investigation for possible use in the treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease. [68][ needs update]

A by mouth formulation of leuprorelin is under development for the treatment of endometriosis. [69] It was also under development for the treatment of precocious puberty, prostate cancer, and uterine fibroids, but development for these uses was discontinued. [69] The formulation has the tentative brand name Ovarest. [69] As of July 2018, it is in phase II clinical trials for endometriosis. [69][ needs update]

Veterinary use

Leuprorelin is frequently used in ferrets for the treatment of adrenal disease. Its use has been reported in a ferret with concurrent primary hyperaldosteronism, [70] and one with concurrent diabetes mellitus. [71] It is also used to treat pet parrots with chronic egg laying behavior. [72]

References

- ^ ELIGARD (Mundipharma Pty Ltd) Department of Health and Aged Care. Retrieved 30 March 2023

- ^ "Product monograph brand safety updates". Health Canada. February 2024. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ "Regulatory Decision Summary for Eligard". Drug and Health Products Portal. 21 September 2023. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ a b c "Lupron- leuprolide acetate lupron- leuprolide acetate injection, solution". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Eligard- leuprolide acetate kit". DailyMed. 26 March 2020. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Fensolvi- leuprolide acetate kit". DailyMed. 3 June 2020. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Viadur- leuprolide acetate". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Lupron Depot- leuprolide acetate kit". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ a b "Camcevi EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 22 March 2022. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Leuprolide Acetate". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ a b World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl: 10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ Silvani M, Mondaini N, Zucchi A (September 2015). "Androgen deprivation therapy (castration therapy) and pedophilia: What's new". Archivio Italiano di Urologia, Andrologia. 87 (3): 222–226. doi: 10.4081/aiua.2015.3.222. hdl: 11568/1073189. PMID 26428645. S2CID 5181746.

- ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 514. ISBN 978-3-527-60749-5. Archived from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ Crosignani PG, Luciano A, Ray A, Bergqvist A (January 2006). "Subcutaneous depot medroxyprogesterone acetate versus leuprolide acetate in the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain". Human Reproduction. 21 (1): 248–56. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei290. PMID 16176939.

- ^ Badaru A, Wilson DM, Bachrach LK, et al. (May 2006). "Sequential comparisons of one-month and three-month depot leuprolide regimens in central precocious puberty". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 91 (5): 1862–67. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1500. PMID 16449344.

- ^ "Lupron, used to halt puberty in children, may cause lasting health problems". STAT. 2 February 2017. Archived from the original on 7 December 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ Clowse ME, Behera MA, Anders CK, Copland S, Coffman CJ, Leppert PC, Bastian LA (March 2009). "Ovarian preservation by GnRH agonists during chemotherapy: a meta-analysis". Journal of Women's Health. 18 (3): 311–19. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.0857. PMC 2858300. PMID 19281314.

- ^ Wolfe DA, Mash EJ (2008). Behavioral and Emotional Disorders in Adolescents: Nature, Assessment, and Treatment. Guilford Press. pp. 556–. ISBN 978-1-60623-115-9. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- ^ Dreger A (January–February 2009). "Gender identity disorder in childhood: inconclusive advice to parents". The Hastings Center Report. 39 (1): 26–9. doi: 10.1353/hcr.0.0102. PMID 19213192. S2CID 22526704.

- ^ Gava G, Mancini I, Alvisi S, Seracchioli R, Meriggiola MC (December 2020). "A comparison of 5-year administration of cyproterone acetate or leuprolide acetate in combination with estradiol in transwomen". European Journal of Endocrinology. 183 (6): 561–569. doi: 10.1530/EJE-20-0370. PMID 33055297. S2CID 222832326.

- ^ Gava G, Cerpolini S, Martelli V, Battista G, Seracchioli R, Meriggiola MC (August 2016). "Cyproterone acetate vs leuprolide acetate in combination with transdermal oestradiol in transwomen: a comparison of safety and effectiveness". Clinical Endocrinology. 85 (2): 239–246. doi: 10.1111/cen.13050. PMID 26932202. S2CID 30150360.

-

^

"Hormone Therapy in Gender Dysphoria" (PDF). NHS Guideline.

Table 1

-

^

"Hormone Therapy in Gender Dysphoria" (PDF). NHS Guideline.

Table 1

- ^ Saleh FM, Niel T, Fishman MJ (2004). "Treatment of paraphilia in young adults with leuprolide acetate: a preliminary case report series". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 49 (6): 1343–48. doi: 10.1520/JFS2003035. PMID 15568711.

- ^ Schober JM, Byrne PM, Kuhn PJ (2006). "Leuprolide acetate is a familiar drug that may modify sex-offender behaviour: the urologist's role". BJU International. 97 (4): 684–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.05975.x. PMID 16536753. S2CID 19365144.

- ^ Schober JM, Kuhn PJ, Kovacs PG, Earle JH, Byrne PM, Fries RA (2005). "Leuprolide acetate suppresses pedophilic urges and arousability". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 34 (6): 691–705. doi: 10.1007/s10508-005-7929-2. PMID 16362253. S2CID 24065433.

- ^ "Common Side Effects of Lupron (Leuprolide Acetate Injection) Drug Center". Archived from the original on 29 July 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2015.[ full citation needed]

- ^ Di Lorenzo G, Autorino R, Perdonà S, De Placido S (December 2005). "Management of gynaecomastia in patients with prostate cancer: a systematic review". Lancet Oncol. 6 (12): 972–79. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70464-2. PMID 16321765.

- ^ Jewett C (2 February 2017). "Women Fear Drug They Used To Halt Puberty Led To Health Problems". Kaiser Health Network. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ Mutschler E, Schäfer-Korting M (2001). Arzneimittelwirkungen (in German) (8 ed.). Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft. pp. 372–73. ISBN 978-3-8047-1763-3.

- ^ Wuttke W, Jarry H, Feleder C, Moguilevsky J, Leonhardt S, Seong JY, Kim K (1996). "The neurochemistry of the GnRH pulse generator". Acta Neurobiologiae Experimentalis. 56 (3): 707–13. doi: 10.55782/ane-1996-1176. PMID 8917899. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015.

- ^ Teutonico D, Montanari S, Ponchel G (March 2012). "Leuprolide acetate: pharmaceutical use and delivery potentials". Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 9 (3): 343–54. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2012.662484. PMID 22335366. S2CID 30843402.

- ^ Butler SK, Govindan R (2010). Essential Cancer Pharmacology: The Prescriber's Guide. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 262–. ISBN 978-1-60913-704-5. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- ^ Lehne RA, Rosenthal R (2014). "Anticancer drugs II: Hormonal agents, targeted drugs, and other noncytotoxic anticancer drugs". Pharmacology for Nursing Care. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 1296–. ISBN 978-0-323-29354-9. Archived from the original on 11 August 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- ^ Su X, Hapani S, Wu S (2011). "An Update on Androgen-Deprivation Therapy for Advanced Prostate Cancer". Prostate Cancer. Demos Medical Publishing. pp. 503–512. ISBN 978-1-935281-91-7. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- ^ "Leuprolide Long-acting – Medical Mutual" (PDF). 21 May 2020. Archived from the original on 11 August 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ "Lupron Depot- leuprolide acetate kit". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ "Lupron Depot- leuprolide acetate kit". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ "Lupron Depot-Ped- leuprolide acetate kit". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Ibrahim A (25 May 2021). "Camcevi (leuprolide) NDA Approval" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ "Lupaneta Pack- leuprolide acetate and norethindrone acetate kit". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ "Lupaneta Pack- leuprolide acetate and norethindrone acetate kit". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ a b Jamil GL (2013). Rethinking the Conceptual Base for New Practical Applications in Information Value and Quality. IGI Global. pp. 111–. ISBN 978-1-4666-4563-9. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- ^ a b c Hara T (2003). Innovation in the Pharmaceutical Industry: The Process of Drug Discovery and Development. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 106–07. ISBN 978-1-84376-566-0. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- ^ Esber EC (21 May 1985). "Lupron (Leuprolide acetate) NDA approval" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Ernst D (4 May 2020). "Fensolvi Approved for Central Precocious Puberty". MPR. Archived from the original on 5 November 2020. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ a b "Camcevi: Pending EC decision". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 24 March 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2022. Text was copied from this source which is copyright European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ "Camcevi Product information". Union Register of medicinal products. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ a b Elks J (2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 730–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ a b Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 599–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ a b Morton IK, Hall JM (2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 164–. ISBN 978-9-401144-39-1. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ a b "Leuprorelin". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 25 February 2018. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ Charatan F (October 2001). "Drug companies defrauded Medicare of millions". BMJ. 323 (7317): 828. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7317.828a. PMC 1121385. PMID 11597964.

- ^ a b c Petersen M (4 October 2001). "2 Drug Makers to Pay $875 Million to Settle Fraud Case". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ a b "#513: 10-03-01 TAP PHARMACEUTICAL PRODUCTS INC. AND SEVEN OTHERS CHARGED WITH HEALTH CARE CRIMES COMPANY AGREES TO PAY $875 MILLION TO SETTLE CHARGES". www.justice.gov. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ "What You Should Know About Lupron Class Action Lawsuit". Law Answer. 8 May 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "Abbott, AbbVie Defeat Long-Running Lupron Bone, Joint Suit (1)". news.bloomberglaw.com. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "More women come forward with complaints about Lupron side effects". KTNV. 12 February 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (30 September 2019). "January - March 2017 | Potential Signals of Serious Risks/New Safety Information Identified by the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS)". FDA.

- ^ Geier M, Geier D (2005). "The potential importance of steroids in the treatment of autistic spectrum disorders and other disorders involving mercury toxicity". Med Hypotheses. 64 (5): 946–54. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2004.11.018. PMID 15780490.

- ^ Allen A (28 May 2007). "Thiomersal on trial: the theory that vaccines cause autism goes to court". Slate. Archived from the original on 3 February 2008. Retrieved 30 January 2008.

- ^ "Testosterone regulation". Research Autism. 7 May 2007. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ^ a b Tsouderos T, Cohn M (11 May 2011). "Maryland medical board upholds autism doctor's suspension". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 21 October 2011.

- ^ "John and Jane Doe v. Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics, Inc" (PDF). US District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina. 6 July 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2008.

- ^ Barrett S (11 July 2012). "Dr. Mark Geier Severely Criticized". Casewatch.net. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020.

- ^ Mills S, Jones T (21 May 2009). "Physician team's crusade shows cracks". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 25 May 2009. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

- ^ "'Miracle drug' called junk science: Powerful castration drug pushed for autistic children, but medical experts denounce unproven claims". Chicago Tribune. 21 May 2009. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013.

- ^ Doraiswamy PM, Xiong GL (2006). "Pharmacological strategies for the prevention of Alzheimer's disease". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 7 (1): 1–10. doi: 10.1517/14656566.7.1.S1. PMID 16370917. S2CID 5546284.

- ^ a b c d "Leuprorelin oral - Enteris BioPharma". Adis Insight. Springer Nature Switzerland AG. Archived from the original on 4 November 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ Desmarchelier M, Lair S, Dunn M, Langlois I (2008). "Primary hyperaldosteronism in a domestic ferret with an adrenocortical adenoma". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 233 (8): 1297–301. doi: 10.2460/javma.233.8.1297. PMID 19180717.

- ^ Boari A, Papa V, Di Silverio F, Aste G, Olivero D, Rocconi F (2010). "Type 1 diabetes mellitus and hyperadrenocorticism in a ferret". Veterinary Research Communications. 34 (Suppl 1): S107–10. doi: 10.1007/s11259-010-9369-2. PMID 20446034.

- ^ "Treatment of Chronic Egg Laying". Yarmouth Veterinary Center. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2020.