Lucy Craft Laney | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | April 13, 1854 |

| Died | October 23, 1933 (aged 79) |

| Education |

Atlanta University University of Chicago Lincoln University South Carolina State College |

| Alma mater | Atlanta University |

| Occupation | Principal |

| Years active | 1886–1933 |

| Employer(s) | Haines Normal and Industrial School |

| Known for | Principal and founder of Haines Normal and Industrial School, Augusta, Georgia |

| Political party | Republican |

Lucy Craft Laney (April 13, 1854 – October 23, 1933) [1] was an American educator who in 1883 founded the first school for black children in Augusta, Georgia. She was principal for 50 years of the Haines Institute for Industrial and Normal Education.

Early life

Lucy Craft Laney was born free on April 13, 1854, in Macon, Georgia, 11 years before slavery was abolished by constitutional amendment after the end of the Civil War. She was the seventh of 10 children born to Louisa and David Laney, free people who were both formerly enslaved. Her father had saved enough money to buy his freedom and that of his wife about 20 years before Lucy's birth. [1] Both her parents were strong believers in education and were very giving to strangers; this upbringing would strongly influence Laney in her life. [2]

At the time of her birth it was illegal in Georgia for black people to learn to read. But with the help of Ms. Campbell, her parents' former enslaver's sister, Lucy learned to read at the age of four. She continued to study and attended Lewis (later Ballard) High School in Macon, Georgia, a mission school run by the American Missionary Association. In 1869 she entered the first class of Atlanta University (later Clark Atlanta University), where she prepared to be a teacher. [3] She graduated from the school's teacher training program (the Normal Department) in 1873. [1]

Teaching career

Laney worked as a teacher in Macon, Milledgeville, and Savannah, Georgia for ten years before deciding to open a school of her own. [4]

Due to health reasons, she settled in Augusta, Georgia, where she founded the city's first school for black children. Her first class in 1883 had six students, but Laney quickly attracted interest in the African-American community. By the end of the second year, the school had 234 students.[ citation needed]

With the increase in students, she needed more funding for her operation. She attended the northern Presbyterian Church Convention in 1886 in Minneapolis, Minnesota and pleaded her case there, but was initially turned down. One of the attendees, Francine E. H. Haines, later declared an interest in and donated $10,000 to Laney for the school. With this money, Laney expanded her offerings. She changed the school's name to The Haines Normal and Industrial Institute in honor of her benefactor and to indicate its goals of industrial and teacher training.[ citation needed]

The school eventually grew to encompass an entire city block of buildings. By 1928, at a time when public education was still segregated, the school's enrollment was more than 800 students. [4]

Haines Normal and Industrial Institute

Haines Normal and Industrial Institute was a school for African Americans in Augusta, Georgia established by Lucy Craft Laney. It was named in honor of a benefactor who funded its expansion. A historical marker was added to the school site in 2009. [5] It eventually became Lucy Craft Laney High School. [6]

Laney opened a school with a few students in 1883. [7] She served as the school's principal. [8] Chartered in 1886, it was expanded with a kindergarten and junior college (Lamar School of Nursing). [9] By 1928, it had more than 800 students. The school also served as a community center. [7]

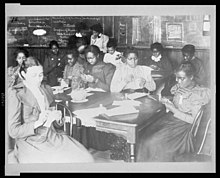

Photographs of the school were gathered by W.E.B. Du Bois and Thomas J. Calloway for the American Negro Exhibit at the Paris Exposition of 1900 (Exposition universelle internationale de 1900). [10] In 1928, negotiation were engaged to have Du Bois speak at the school. [11]

It was supported by the Presbyterian Board of National Missions. A.C. Griggs served as president of the school. [12]

Sewing, laundry, and printing were taught in a building on the campus. An entity on the school appeared in James T. Haley's Afro-American Encyclopaedia. [13]

NAACP and other organizations

While living in Augusta, Laney joined the Niagara Movement, founded in 1905. Later in 1918 she helped to found the local chapter of the successor civil rights organization, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). She was also active in other organizations to promote the welfare of blacks and black women: the Interracial Commission, and the National Association of Colored Women. She also helped to integrate the community work engaged in by the YMCA and YWCA (which had separate organizations for white and black residents, respectively). [1]

Honors and recognition

In 1974, Governor Jimmy Carter arranged to hang the first portraits of African Americans in the Georgia state capitol to honor their contributions: included were Lucy Craft Laney, the Reverend Henry McNeal Turner, and the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. In 1992, Laney was inducted into " Georgia Women of Achievement." [1]

Personal life

Laney died on October 23, 1933, [14] and is buried at the corner of Laney Walker Boulevard and Phillips Street, where she first founded the Haines Normal and Industrial Institute. [15]

Legacy

The site of Laney's burial was redeveloped for the Lucy Craft Laney Comprehensive High School, named in her honor. Her grave and memorial remain undisturbed. [4] [15]

Other schools named for her are:

- Lucy Laney Elementary School in Harris County, Georgia [16]

- Lucy Craft Laney Community School, serving PK-5th grade students in North Minneapolis, Minnesota

References

- ^ a b c d e "Lucy Craft Laney (1854–1933)". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ^ Feger, H. V. (1942). "A Girl Who Became a Great Woman". Negro History Bulletin. 5 (6): 123. ISSN 0028-2529. JSTOR 44246284.

- ^ Leslie, Kent Anderson. "Lucy Craft Laney". The New Georgia Encyclopedia. Georgia Humanities Council and the University of Georgia Press. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ a b c Yenser, Thomas, ed. (1933). Who's Who in Colored America: A Biographical Dictionary of Notable Living Persons of African Descent in America 1930-1931-1932 (Third ed.). Brooklyn, New York: Who's Who in Colored America.

- ^ "Haines Normal and Industrial Institute". Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ "CONTENTdm". vault.georgiaarchives.org. Retrieved November 8, 2022.

- ^ a b "Haines Normal and Industrial Institute". The PBS Blog. July 5, 2018.

- ^ "Lucy Craft Laney (1854-1933)". New Georgia Encyclopedia.

- ^ "Haines Normal and Industrial Institute Historical Marker". hmdb.org. Retrieved November 8, 2022.

- ^ "Teachers and students at Haines Normal and Industrial Institute, Augusta, Ga". Library of Congress. Retrieved November 8, 2022.

- ^ "Letter from unidentified correspondent to Haines Institute". digitalcommonwealth.org. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ "Haines Institute in Augusta, Georgia - Crisis Magazine, August, 1940". August 29, 2014. Retrieved April 19, 2021 – via Flickr.

- ^ "James T. Haley. Afro-American Encyclopaedia; or, the Thoughts, Doings, and Sayings of the Race, Embracing Lectures, Biographical Sketches, Sermons, Poems, Names of Universities, Colleges, Seminaries, Newspapers, Books, and a History of the Denominations, Giving the Numerical Strength of Each. In Fact, it Teaches Every Subject of Interest to the Colored People, as Discussed by More Than One Hundred of Their Wisest and Best Men and Women". Retrieved November 8, 2022.

- ^ "Lucy Laney Dies At Augusta Home". The Macon Telegraph. October 24, 1933. Retrieved August 31, 2022.

- ^ a b "Lucy Craft Laney", GeorgiaHistory.com. Accessed November 8, 2022.

- ^ Seibert, David. "Lucy Laney Elementary School". GeorgiaInfo: an Online Georgia Almanac. Digital Library of Georgia. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

External links

- Lucy Laney Elementary School historical marker

- Lucy Craft Laney at Find a Grave

- 1854 births

- People from Macon, Georgia

- People from Augusta, Georgia

- Clark Atlanta University alumni

- 1933 deaths

- Georgia (U.S. state) Republicans

- 19th-century American educators

- 19th-century American women educators

- 20th-century American educators

- 20th-century American women educators

- Educators from Georgia (U.S. state)

- 20th-century African-American women

- 20th-century African-American educators

- 19th-century African-American educators