| Invasion of Algiers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French conquest of Algeria | |||||||

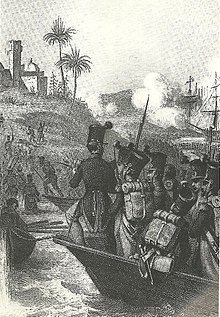

Attaque d'Alger par la mer 29 Juin 1830, Théodore Gudin | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

Makhzen tribal levy [2] | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Expeditionary army:

3,988 horses Naval forces: 103 warships 464 transport ships 27,000 sailors [7] | 25,000-50,000 [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

415 killed 2,160 wounded [13] [14] [15] | over 5,000 [16] | ||||||

The invasion of Algiers in 1830 was a large-scale military operation by which the Kingdom of France, ruled by Charles X, invaded and conquered the Deylik of Algiers.

Algiers was annexed by the Ottoman Empire in 1529 after the capture of Algiers in 1529 and had been under direct rule until 1710, when Baba Ali Chaouch achieved de facto independence from the Ottomans, though the Regency was still nominally a part of the Ottoman Empire. [17]

The Deylik of Algiers elected its rulers through a parliament called the Divan of Algiers. These rulers/kings were known as Deys. The state could be best described as an Elective monarchy. [18]

A diplomatic incident in 1827, the so-called Fan Affair (Fly Whisk Incident), served as a pretext to initiate a blockade against the port of Algiers. After three years of standstill and a more severe incident in which a French ship carrying an ambassador to the dey with a proposal for negotiations was fired upon, the French determined that more forceful action was required. Charles X was also in need of diverting attention from turbulent French domestic affairs that culminated with his deposition during the later stages of the invasion in the July Revolution.

The invasion of Algiers began on 5 July 1830 with a naval bombardment by a fleet under Admiral Duperré and a landing by troops under Louis Auguste Victor de Ghaisne, comte de Bourmont. The French quickly defeated the troops of Hussein Dey, the Deylikal ruler, but native resistance was widespread. This resulted in a protracted military campaign, lasting more than 45 years, to root out popular opposition to the colonization. The so-called "pacification" was marked by resistance of figures such as Ahmed Bey, Abd El-Kader and Lalla Fatma N'Soumer.

The invasion marked the end of the several centuries old Regency of Algiers, and the beginning of French Algeria. In 1848, the territories conquered around Algiers were organised into three départements, defining the territories of modern Algeria.

Background

This section needs additional citations for

verification. (June 2021) |

During the Napoleonic Wars, the Kingdom of Algiers had greatly benefited from trade in the Mediterranean, and of the massive imports of food by France, largely bought on credit. The Dey of Algiers attempted to remedy his steadily decreasing revenues by increasing taxes, which was resisted by the local peasantry, increasing instability in the country and leading to increased piracy against merchant shipping from Europe and the young United States of America. This, in turn, led to the First Barbary War and the Second Barbary War, which culminated in August 1816 when Lord Exmouth executed a naval bombardment of Algiers in response to Algerian massacres of recently freed European slaves.

The widespread unpopularity of the Bourbon Restoration among the French populace at large also made France unstable. In an attempt to distract his people from domestic affairs, King Charles X decided to engage in a colonial expedition.

In 1827, Hussein Dey, Algeria's Dey, demanded that the French pay a 28-year-old debt contracted in 1799 by purchasing supplies to feed the soldiers of the Napoleonic Campaign in Egypt. The French consul Pierre Deval refused to give answers satisfactory to the dey, and in an outburst of anger, Hussein Dey touched the consul with his fly-whisk. Charles X used this as an excuse to initiate a blockade against the port of Algiers. The blockade lasted for three years, and was primarily to the detriment of French merchants who were unable to do business with Algiers, while Barbary pirates were still able to evade the blockade. When France in 1829 sent an ambassador to the dey with a proposal for negotiations, he responded with cannon fire directed toward one of the blockading ships. The French then determined that more forceful action was required. [19]

King Charles X decided to organise a punitive expedition on the coasts of Algiers to punish the "impudence" of the dey, as well as to root out Barbary corsairs who used Algiers as a safe haven. The naval part of the operation was given to Admiral Duperré, who advised against it, finding it too dangerous. He was nevertheless given command of the fleet. The land part was under the orders of Louis Auguste Victor de Ghaisne, comte de Bourmont.

On 16 May, a fleet comprising 103 warships and 464 transports departed Toulon, carrying a 37,612-man strong army. The ground was well-known, thanks to observations made during the First Empire, and the Presque-isle of Sidi Ferruch was chosen as a landing spot, 25 kilometres (16 mi) west of Algiers. The vanguard of the fleet arrived off Algiers on 31 May, but it took until 14 June for the entire fleet to arrive.

Order of battle

- Provence (74), flagship. Admiral Duperré

- Marengo (74)

- Trident (74)

- Duquesne (80), captain Bazoche

- Algésiras (80)

- Conquérant (80)

- Breslaw (80)

- Couronne (74)

- Ville de Marseille (74), en flûte

- Pallas (60),

- Melpomène (60),

- Aréthuse (46), en flûte

- Pauline (44)

- Thétis (44)

- Proserpine (44)

- Sphinx

- Nageur

Algerian preparations

Following the rise in tension and the start of the war, the Algerians mobilized themselves. The tribes of the Makhzen system were levied throughout the Beyliks of Constantine, Oran, and Titteri. [20] The Zwawa and Iflissen warrior tribes of Kabylia were also levied, and were given under the command of Cheikh Mohammed ben Zaamoum. [1] The Odjak of Algiers was also mobilized, and their Agha, Ibrahim was appointed as supreme commander of the Algerian forces. As Hussein Dey declared a holy Jihad against the French invaders, many volunteers from throughout the country joined the army of Hussein Dey. [1] Furthermore several letters were sent to specific tribes whom were renown for their martial prowess throughout the country.

“Good day to all the people of Kabylia and to all their notables and their marabouts. Know that the French formed the design to land and seize the capital of Algiers. You are a people renowned for your courage and your dedication to Islam. The Ujaq calls you to holy war so that you may reap the benefits, in this world and in the next, like your ancestors who fought in the First Holy War against Charles V in 1541. Whoever wants to be happy in the next world, must devote himself entirely to Jihad when the time is right. Jihad is a duty imposed on us by religion, when the infidel is in our territory.”

From a letter sent by Ibrahim Agha to several Kabyle tribes, such as the Ait Iraten. [21]

The exact number and composition of the Algerian army is unknown, but it is known that the majority of troops were from the Makhzen tribal levy. Estimates of the exact number of Algerian troops vary greatly, with some estimates putting it at about 25,000-30,000 [22] while some French sources putting it at 50,000.

Invasion

French landing

On the morning of 14 June 1830, the French Expeditionary Force composed of 34,000 soldiers divided in three divisions, started disembarking on the Sidi Ferruch Presque-isle. After landing, they quickly captured the Algerian battery and the division under general Berthezène established a beachhead to protect the landing of the rest of the troops. While the French were preparing, they were constantly attacked and harassed by hidden Algerian scouts, whose guerrilla-style harassment was only a prelude to the main attack. [23]

Battle of Staoueli

As the French were slowly disembarking their troops and equipment, Hussein Dey's three Beys, from Oran, Titteri and Medea, and various caids had answered the call to arms and started gathering forces in a large camp on the nearby plateau of Staoueli. Convinced that fear alone was keeping the French from making any move forward, the Algerian forces, led by Ibrahim Agha, came down from the plateau on the early morning of 19 June and attacked the two French divisions that had already disembarked. [24] The Algerian assault was repulsed and the French forces followed the Algerians to their camp up the hill. [25] French artillery fire and bayonet charges eventually turned the Algerian retreat into a general rout. [26] By midday the French had captured the Algerian camp and many of the forces assembled by the Dey went back home. In the camp, the French found riches, weapons, food and livestock that the Algerians had abandoned there while they fled. [27]

Despite the French success, Bourmont decided not to move any further until all the forces had been disembarked. Meanwhile, in Algiers, Hussein Dey spent the next three days actively trying to gather the forces that had scattered after the battle. [28] Everyday more and more of them arrived to the city, and soon the apparent inaction of the French gave the Algerians renewed confidence. [29]

Battle of Sidi Khalef

On the morning of 24 June, Algerian forces came back on Staoueli plateau and deployed themselves in front of French outposts. [28] As the 1st French division started marching toward them in column formation, Algerian forces retreated toward the village of Sidi Khalef at the edge of the plateau. [28] [30] After some fighting, the Algerians were routed by a bayonet charge. [31] French casualties were very low on that day, but Amédée de Bourmont, one of the French commander-in-chief's four sons, was among the killed. [31]

Bombing of Algiers

On July 3, Admiral Duperré and some of his warships bombed Algiers coastal defences. However, French ships remained relatively far from the coast and thus caused only slight damage. [32] [33]

Siege of Bordj Moulay Hassan fortress

On 29 June, French troops arrived near the Bordj Moulay Hassan fortress, an old Ottoman fortress that the French soon nicknamed "Fort de l'Empereur" as tribute to Emperor Charles V, since it had been built in response to his attack on the city in 1541. On 30 June they started digging trenches in preparation for the siege and by July 3 they had brought all their artillery. In the early morning of July 4, general De la Hitte, commander of the French artillery, ordered all batteries to open fire. [34]The defenders immediately returned fire, and a long cannonade ensued. The fort's garrison, composed of about 800 janissaries and 1,200 Moors, [35] resisted for several hours despite the intense bombardment they were subjected to, a feat of courage that impressed the French. [36] Near 10:00 am however, the defenders of the fort stopped firing as they no longer had any cover after all the merlons had been destroyed. [37] The fortress was devastated and most of its guns had been destroyed. The defenders then gathered what was left of powder and blew up the fortress before fleeing the place. [38] Out of the 2,000 men of the garrison, only half had survived and returned to the Casbah [34]

Capitulation of Algiers

With the fortress out of the picture, the city was now at the mercy of the French invasion force. The French brought their artillery in the ruins of the fortress started exchanging fire with the Casbah of Algiers. [39]

A little after midday, an envoy of the Dey reached French lines and attempted to negotiate a French withdrawal in exchange for an official apology to the King of France and the repayment of French war expenditures by the Regency. [40] [41] The French refused, and a while later two delegates came to the French and negotiated an armistice until peace agreements could be reached. They also proposed to bring the head of the Dey to the French, which the French declined. [40] [39] De Bourmont told them that France wanted the city, its fleet, the Regency's treasury and the departure of Turks from the city and promised to spare the inhabitants houses from pillaging if these terms were accepted. Hussein Dey would also be allowed to bring his personal wealth with him in exile. [42] The two delegates left and came back on the next day at about 11:00 am, and told the French that the Dey agreed to their terms. [43] French troops entered the city on July 5 at 12:00. [34]

A few days later, Hussein Dey and his family embarked on a frigate and departed for Naples. [44]

Effects

With the French invasion of Algiers, a number of Algerians migrated west to Tetuan. They introduced baklava, coffee, and the warqa pastry now used in pastilla. [45] [46]

References

- ^ a b c Karim, L.A. (2016). Côte ouest d'Alger (in Walloon). Auteur. p. 56. ISBN 978-9947-0-4621-0. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- ^ Ajayi, J.F.A. (1989). Africa in the Nineteenth Century Until the 1880s. General history of Africa. UNESCO. p. 500. ISBN 978-92-3-101712-4. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- ^ D'Ault-Dumesnil, Edouard (1868). Relation de l'Expédition d'Afrique en 1830 et de la conquête d'Alger. Lecoffre. p. 131.

- ^ McDougall 2017, p. 51.

- ^ Bulletin universel des sciences et de l'industrie. 8: Bulletin des sciences militaires, Volume 11. Didot. 1831. p. 80.

- ^ Pellissier de Reynaud, Henri (1836). Annales Algériennes, Volume 1. Gaultier-Laguionie. p. 24.

- ^ Achille Fillias (1865). Nouveau. guide general du voyageur en Algerie par ---(etc.). Garnier. pp. 33–.

- ^ "Sur la terre d'Afrique !". www.algerie-ancienne.com. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ McDougall, James (2017). A History of Algeria. Cambridge University Press. p. 52]. ISBN 9781108165747.

- ^ De Quatrebarbes, Théodore (1831). Souvenirs de la campagne d'Afrique. Dentu. p. 35.

- ^ Faivre d'Arcier, Charles Sébastien (1895). Historique du 37e régiment d'infanterie, ancien régiment de Turenne, 1587-1893. Delagrave. p. 223.

- ^ Watson 2003, p. 20.

- ^ "Conquête d'Alger ou pièces sur la conquête d'Alger et sur l'Algérie". 1 January 1831 – via Google Books.

- ^ Miroir de l'histoire, Numéros 247 à 25. Nouvelle librairie de France. 1970. p. 33.

- ^ Watson, William E. (2003). Tricolor and Crescent: France and the Islamic World. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 20. ISBN 9780275974701.

- ^ De Quatrebarbes 1831, p. 40.

- ^ Association, American Historical (1918). General Index to Papers and Annual Reports of the American Historical Association, 1884-1914. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ Mahfoud Kaddache, L'Algérie des Algériens, EDIF 2000, 2009, p. 413

- ^ Abun-Nasr, Jamil (1987). A history of the Maghrib in the Islamic period. Cambridge University Press. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-521-33767-0.

- ^ Rousset, Camille (1879). La conquête d'Alger. Plon-Nourrit. p. 135.

- ^ Chachoua, Kamel (2000). Zwawa et zawaya: l'islam "la question kabyle" : et l'État en Algérie. Autour de la Rissala, épître, "Les plus clairs arguments qui nécessitent la réforme des zawaya kabyles", d'Ibnou Zakri (1853-1914), clerc officiel dans l'Algérie coloniale, publiée à Alger, aux Editions Fontana en 1903 (in French). Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales.

- ^ A bis Arad (in German). Brockhaus. 1864.

- ^ Gaskell, George (1875). Algeria as it is. Smith, Elder & Company.

- ^ Rousset 1879, p. 138.

- ^ Rousset 1879, p. 147.

- ^ Rousset 1879, p. 156.

- ^ Blakesley 1859, p. 69.

- ^ a b c Rousset 1879, p. 164.

- ^ D'Ault-Dumesnil 1868, p. 258.

- ^ D'Ault-Dumesnil 1868, p. 259.

- ^ a b Rousset 1879, p. 168.

- ^ Pellissier de Reynaud 1854, p. 64.

- ^ Rousset 1879, p. 207.

- ^ a b c D'Ault-Dumesnil 1868, p. 314.

- ^ Rousset 1879, p. 314.

- ^ D'Ault-Dumesnil 1868, p. 317.

- ^ Pellissier de Reynaud 1854, p. 51.

- ^ Rousset 1879, p. 212.

- ^ a b Rousset 1879, p. 215.

- ^ a b De Quatrebarbes 1831, p. 63.

- ^ Rousset 1879, p. 214.

- ^ De Quatrebarbes 1831, p. 64.

- ^ De Quatrebarbes 1831, p. 65.

- ^ De Quatrebarbes 1831, p. 70.

-

^ Gaul, Anny (27 November 2019).

"Bastila and the Archives of Unwritten Things". Maydan. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

I was especially interested in Tetouani baqlawa, a pastry typically associated with the eastern Mediterranean, not the west. The baqlawa we sampled was shaped in a spiral, unlike the diamond-shaped version I was more familiar with from Levantine food. But its texture and flavors––thin buttered layers of crisp papery pastry that crunch around sweet fillings with honeyed nuts––were unmistakable. Instead of the pistachios common in eastern baqlawa, El Mofaddal's version was topped with toasted slivered almonds. Was baqlawa the vehicle that had introduced phyllo dough to Morocco?

There is a strong argument for the Turkic origin of phyllo pastry, and the technique of shaping buttered layers of it around sweet and nut-based fillings was likely developed in the imperial kitchens of Istanbul.[4] So my next step was to find a likely trajectory that phyllo dough might have taken from Ottoman lands to the kitchens of northern Morocco.

It so happened that one of Dr. BejjIt's colleagues, historian Idriss Bouhlila, had recently published a book about the migration of Algerians to Tetouan in the nineteenth/thirteenth century. His work explains how waves of Algerians migrated to Tetouan fleeing the violence of the 1830 French invasion. It includes a chapter that traces the influences of Ottoman Algerians on the city's cultural and social life. Turkish language and culture infused northern Morocco with new words, sartorial items, and consumption habits––including the custom of drinking coffee and a number of foods, especially sweets like baqlawa. While Bouhlila acknowledges that most Tetouanis consider bastila to be Andalusi, he suggests that the word itself is of Turkish origin and arrived with the Algerians."

...

"Bouhlila's study corroborated the theory that the paper-thin ouarka used to make bastila, as well as the name of the dish itself, were introduced to Morocco by way of Tetouani cuisine sometime after 1830. - ^ Idriss Bouhlila. الجزائريون في تطوان خلال القرن 13هـ/19م. pp. 128–129.

Sources

- Blakesley, Joseph William (1859). Four months in Algeria with a visit to Carthage. McMillan and Co.

- Pellissier de Reynaud, Edmond (1854). Annales algériennes, Volume 1. Paris: Librairie Militaire.

- Battles of the French conquest of Algeria

- Conflicts in 1830

- 1830 in Algeria

- 19th century in Algiers

- Sieges involving the Regency of Algiers

- Sieges involving France

- Invasions by France

- Invasions of the Ottoman Empire

- 1830 in the Ottoman Empire

- June 1830 events

- July 1830 events

- Amphibious operations

- Sieges of Algiers