This article is missing information about North Korean newspapers. (April 2023) |

Modern newspapers have been published in Korea since 1881, with the first native Korean newspaper being published in 1883.

Joseon period

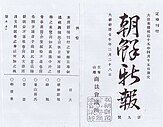

Chōsen Shinpō

The history of modern newspapers in Korea begins in the Joseon period, with the publication of the Japanese newspaper Chōsen Shinpō on December 10, 1881. [1] [2] It was the first modern newspaper to be published in Korea. [1] [3] [2] Japan's own first newspaper, the 1861 Nagasaki Shipping List and Advertiser, was published in English by an Englishman. [4] Twelve issues of the Chōsen Shinpō are known to exist. Its articles are published mostly in Japanese or Classical Chinese (which educated Koreans would have been able to read), but it did have one article that was known to have been published in the Korean script Hangul. [3]

Japanese newspapers went on to have a significant influence in Korean newspaper history. However, after the Chōsen Shinpō, new Japanese newspapers did not arise in Korea until around 1890. Scholar Park Yong-gu (박용구) speculates that it may have been because of worsened Japan–Korea ties after the 1882 Imo Incident. [5]

Hansŏng sunbo and Hansŏng jubo

Korean emissaries visited China and Japan and noticed the proliferation of newspapers there. Park Yung-hyo convinced the Korean monarch Gojong to allow the creation of a Korean newspaper, and brought Japanese printing equipment and advisors to Seoul to create a paper. [6] Hansŏng sunbo was published on October 31, 1883 as the first native Korean newspaper, although it was written in Classical Chinese. [6] Subscriptions were sold to both public servants and private citizens, although likely public servant readers were more common. [6] [7] The newspaper stopped circulating in December 1884, more than a year after its launch, due to the Gapsin Coup. Hansŏng jubo (한성주보; 漢城周報) was founded as a weekly successor paper on January 25, 1886 and was eventually shut down in 1888 due to a lack of government funds. [8] [7]

Early Japanese publications in Korea

The first private Korean newspaper would not emerge until 1896. [9] [10] Until then, most newspapers published in Korea were Japanese. [11] Japanese traders and settlers began arriving in increasing numbers over time. [12] [13]

| Year | Busan | Wonsan | Incheon | Seoul |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 2,066 | 207 | 0 | 0 |

| 1885 | 1,896 | 235 | 562 | 89 |

| 1890 | 2,733 | 708 | 1,554 | 522 |

| 1895 | 4,953 | 1,362 | 4,418 | 1,519 |

In particular, Incheon's Japanese population saw a notable increase by 1890. Correspondingly, Japanese newspapers began to emerge there for the settlers, [13] with the Jinsen Keijō Kakushū Shōhō (later called Chōsen Shinpō, unrelated to the 1881 publication) being founded there around that time. [14] This and other Japanese papers in the 1890s often primarily wrote on news and statistics about commerce, with current events being a secondary concern. [14]

The 1894–1895 First Sino-Japanese War was a significant period for the few Japanese newspapers in Korea. The Japanese government intervened directly in the affairs of the papers, [15] and even issued an order (No. 134) that newspapers consult authorities before publishing anything potentially controversial about the war. [16] Some papers went on hiatus, potentially due to the war, around this time. [14] In May 1895, the Japanese consulate in Korea received confirmation that it could censor newspapers in Korea like the mainland Japanese government could in Japan. [16]

A notable population among Japanese settlers in Korea were aggressive young men often dubbed sōshi (壮士). [12] In Korea, they had the right of extraterritoriality and could not be punished under Korean law. Many committed violent crimes, and felt emboldened by their status. [17] A number of them settled into careers as journalists, [12] with many having little prior experience in the field. [11] Closely adjacent to this group was Adachi Kenzō, who founded the newspapers Chōsen Jihō in Busan in 1894, and Kanjō Shinpō in Seoul around 1894 or 1895. [11] The papers were initially popular with Koreans, as they published general and useful information. [11] Their technology and style likely inspired and contributed to the later proliferation of Korean newspapers. [11] [18] However, after Adachi enlisted all of the Kanjō Shinpō staff to assassinate the Korean queen in late 1895, [19] sentiment shifted against Adachi's papers and Japan in general. [20] [11] Japanese newspaper began to publish more overtly along Japanese lines, criticizing Korean culture and politicians. [20] [11]

Tongnip Sinmun

On April 7, 1896, the first private Korean newspaper, Tongnip Sinmun, was founded. [9] [10] It was also the first newspaper to publish purely in Hangul, which was revolutionary for the time. It also was a significant early adopter of spaces between words. [10] It published in both Korean and English, with its English name being The Independent. True to its name, it promoted Korean independence activism and promoted reforms in order to prevent Korea's future subjugation. [10]

Korean Empire period

Rise of private Korean newspapers

More Korean papers soon followed the Tongnip Sinmun, with the following being founded in 1898 alone: Kyŏngsŏng Sinmun, [21] Cheguk Sinmun, [22] Hyŏpsŏnghoe Hoebo, [23] Hwangsŏng Sinmun, [24] and Maeil Sinmun. [25] Around this time, the Tongnip Sinmun increased its publication frequency from every other day to daily. [10]

At the time, Korea had no legislation in place to manage these newspapers. [26] They published critically about foreign interference in Korea, and also criticized the Korean government for falling prey to the interference. For example, in February 1898, the Tongnip Sinmun leaked information about the Russian Empire demanding ownership of Busan's Chŏryŏngdo from the Korean government. The emissaries of Russia, France, and Japan protested the leak, and demanded that Gojong enact legislation to regulate Korean newspapers. [26] In October, [10] Gojong issued an order to draft such a law. The Department of Internal Affairs drafted a bill modeled after Japan's 1891 newspaper ordinance. The bill was seen as too harsh, and Korean journalists protested it. The bill never ended up taking effect; formal restrictions on Korean newspapers were only implemented beginning in 1907. [26] [10]

During the 1904–1905 Russo-Japanese War, the Korean press leaked Japanese military movements and secrets on a number of occasions. [10] Japan submitted a number of complaints to Gojong, and the Japanese military threatened to intervene and censor the papers by force. [10] Several newspapers had some of their articles censored. In protest of this, they began to practice what was dubbed "brick wall newspaper" (벽돌신문) tactics, where they printed censored articles backwards. [10]

Japanese response

The Japanese legation, which had once held significant sway over the Korean media landscape, began making greater efforts to compete. [27] It invested and intervened in the affairs of its existing newspapers, [28] and provided funding for the creation of new papers. [27] [29] In the late 1890s and early 1900s, various Japanese newspapers were founded in major urban centers, including Wonsan, Mokpo, Gunsan, and Daegu. They were rarely published as daily papers, and some of them were published for only small Japanese populations. Park Yong-gu theorizes that their publication was meant to promote community identity and ties, [30] as well as to provide careers for Japanese immigrants. [31]

Upon Japan's victory in the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, Korea was forced to be put under the indirect rule of the Japanese Resident-General of Korea. [10] Resident-general Itō Hirobumi began work on changing the press landscape of Korea, as well as influencing international opinion on Korea's eventual colonization. [32] [10] He set up a network of interlinked media presences in Tokyo, Seoul, and New York City. [32] For English-language press, Itō worked with his Anglo-Irish acquiantance John Russell Kennedy. [32]

| Year | # newspapers | Population |

|---|---|---|

| 1904 | 11 | 31,093 |

| 1905 | 14 | 42,460 |

| 1906 | 27 | 83,315 |

| 1907 | 34 | 98,001 |

| 1908 | 32 | 126,168 |

| 1909 | 34 | 146,147 |

| 1910 | 28 | 171,543 |

Meanwhile, the Japanese population and number of Japanese newspapers in Korea nearly doubled from 1905 to 1906. [33] Newspapers began to be founded for the first time in various Korean cities, with the first newspapers in Jeonju, [34] Masan, [35] and Daejeon being Japanese. [36] By contrast, the only regional Korean-language newspaper that was founded during this period was the Gyeongnam Ilbo. [37]

| Location | Newspaper name | Circulation |

|---|---|---|

| Incheon | Chōsen Shinpō | 8,529 |

| Daejeon | Sannan Shinpō | 360 |

| Busan | Chōsen Jihō | 2,412 |

| Busan | Fuzan Nippō | 2,400 |

| Masan | Masan Shinpō | 841 |

| Daegu | Taikyū Shinbun | 1,150 |

| Gwangju | Kōshū Shinpō | 514 |

| Mokpo | Moppo Shinpō | 732 |

| Jeonju | Zenshū Shinpō | 480 |

| Gunsan | Genzan Nippō | 649 |

| Pyongyang | Heijō Nippō | 852 |

| Pyongyang | Heijō Shinbun | 833 |

| Chinnamp'o | Chinnanpo Shinpō | 750 |

| Sinuiju | Ōkō Nippō | 485 |

| Wonsan | Genzan Mainichi Shinbun | 1,556 |

| Hamhung | Minyū Shinbun | 946 |

| Chongjin | Kitakan Shinbun | 1,567 |

In several cities, even those with smaller markets, multiple Japanese newspapers formed, which led to competition between them. Several regional newspapers were acquired, merged, or split off from each other over the course of the 1900s. [39] They mostly published in Japanese, although several of them published some articles in Korean. Historian Park Yong-gu notes that this was primarily done to profit from the Korean market as well, although some articles did attempt to justify Japan's takeover of Korea. [40] However, Park also argues that the proliferation of Korean-language articles in Japanese papers possibly negatively impacted the creation of native Korean newspapers. In Daegu in 1906, the Korean publisher Kwangmunsa received permission to create a newspaper, but never ended up doing so. This was possibly because the local Japanese paper began publishing articles in Korean around this time, which may have decreased demand for a new Korean newspaper. [41]

Park points out that the local Japanese newspapers were sometimes troublesome for Japanese government; in several instances, newspapers were suspended or closed because they published pieces critical of the government, and regulations were increasingly applied to their management. [42]

| Name | Date | Punishment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taikyū Nippō | December 1906 | Publication suspended | Published a critical article |

| Taikyū Nichi Nichi Shinbun | February 1907 | Extradited to Japan (퇴한령; 退韓令) | |

| Taikyū Nichi Nichi Shinbun | April 10, 1908 | Extradited to Japan (퇴한령; 退韓令) | Suspended for two years afterwards |

| Chōsen Times | April 17, 1908 | Publication suspended | For a critical article, lifted on April 23 |

| Chōsen Times | May 23, 1908 | Sales suspended | |

| Fuzan Nippō | May 26, 1908 | Sales suspended | |

| Chōsen Times | October 3, 1908 | Sales suspended | Revealed Japanese troop movements |

| Chōsen Shinpō | October 3, 1908 | Sales suspended | Revealed Japanese troop movements |

| Moppo Shinpō | March 3, 1910 | Sales suspended | For disturbing governance |

| Heijō Nippō | April 1910 | Sales suspended | |

| Heijō Nippō | June 12, 1910 | Sales suspended | For an article about Japan's takeover of Korea |

| Fuzan Nippō | August 5, 1910 | Publication suspended | For an article about current events |

| Chōsen Shinpō | August 5, 1910 | Publication suspended | |

| Chōsen Shinbun | August 10, 1910 | Sales suspended | For disturbing governance, lifted on August 12. |

| Heijō Nippō | August 11, 1910 | Sales suspended, publication suspended | For disturbing governance, lifted on August 14. |

| Heijō Shinbun | August 26, 1910 | Publication suspended, sales suspended | For disturbing governance, lifted on August 27. |

The Japanese resident-general continued financially supporting various Japanese newspapers in Korea, although Park Yong-gu was uncertain about when this practice stopped. Park theorized that, over time, the need for support decreased, as Japanese newspapers attracted more readers and advertisers. [44]

The Korea Daily News and newspaper censorship

The Korea Daily News was an English-language newspaper published in the Korean Empire between 1904 and 1910. It had two companion Korean-language editions published in mixed script and pure Hangul called Taehan Maeil Sinbo. It is the first predecessor to modern Seoul Shinmun, which is the oldest running daily newspaper in South Korea. [45] [46]

The newspaper is remembered as a hub of the Korean independence movement around that time. The newspaper's owner, British journalist Thomas Bethell, dodged Japanese censorship using his foreign citizenship, and sharply criticized Japan. He worked alongside notable Korean independence activists, especially Yang Gi-tak. [45] [46]

Japan moved to stifle the publication. In January 1906, press secretary Zumoto Motosada purchased the English-language The Seoul Press on behalf of the resident-general, and used it to directly counter Bethell's paper. [32] [47] Furthermore, in 1906, the Japanese resident-general purchased and centralized several Japanese newspapers, including the Kanjō Shinpō and Daitō Shinpō, which resulted in the creation of the Keijō Nippō. [48] This newspaper became the de facto publication of the Japanese resident-general and later governor-general, and held a position of prominence in Korea until its dissolution in 1945. [49] [50] The Japanese resident-general also passed two significant pieces of legislation in Korea to hamper the Korean press. The first was the Newspaper Law (新聞紙法; 신문지법) of 1907, then came the Publication Law (出版法; 출판법) of 1909. [32] [10] These laws were eventually abolished years after the liberation of Korea: on March 19, 1952. [10]

Issues of Korean-language newspapers were prohibited and confiscated in significant numbers around this time. According to a 1909 Japanese resident-general report, they had confiscated a total of 20,947 issues of various newspapers, even those published abroad in Russia and the United States, by that point. [51]

By request from the Japanese resident-general, the British consulate arrested and tried Bethell twice for his reporting. He was eventually found innocent, although the stress from his legal troubles possibly caused his early death in 1909 from a heart issue. The paper was subsequently sold, and by 1910 it became an organ of the Japanese government called Maeil Sinbo. [45] [46]

Gyeongnam Ilbo

Gyeongnam Ilbo was the first ever, and only regional Korean-language newspaper founded during this period. [37] It was also the first newspaper in Jinju. It was founded on October 15, 1909. [53] [54] [52] Its company was also the first publicly-owned Korean press company. [53] The newspaper's founding was hailed by other Korean and even Japanese and Chinese newspapers. [54] [53] It published critically about Japan until the beginning of the colonial period. It was then censored and suppressed, with increasing financial and political pressure applied to its staff. [53] [54] [52] It eventually halted publication in January 1915, although the newspaper eventually restarted twice after the liberation of Korea, and still persists to this day. [52] [53] [54]

Japanese colonial period

From 1910 until the 1919 March 1st Movement, few Korean-language publications were allowed in Korea. [10] According to an article in the Encyclopedia of Korean Culture, this period can be considered a "dark age" for the Korean-language press. [10] Only two Korean-language papers were allowed, the Maeil Sinbo and the Gyeongnam Ilbo, and the latter was pressured to close by 1914. [10] [55]

South Korean historian Kang Jun-man (강준만) noted the disparity between the ratio of Japanese publications and readers vs. Korean publications and readers in 1910. At least 20 Japanese-language publications were published for around 158,000 Japanese people, compared to just two for 12.36 million Koreans. [55]

The March 1st Movement and native Korean newspapers

In January 1919, the Korean monarch Gojong suddenly died. Rumors emerged that Gojong had been poisoned by Japan, and the Korean population was outraged. They launched a peaceful protest in which they advocated for independence. Millions protested across the country. However, the protests were violently suppressed by the Japanese authorities, resulting in numerous deaths and arrests. The movement invigorated the Korean independence movement, [56] and around 29 underground Korean nationalist newspapers were founded in Korea soon afterwards. [10]

In response to the protests, the Japanese colonial government changed many of its policies, [56] and eased restrictions on Korean newspapers. [10] Three Korean-language newspapers were approved for publication in 1920: [10] The Chosun Ilbo, The Dong-A Ilbo, [57] and the pro-Japanese publication Sisa Ch'ongbo, although the last of which closed the following year. [10] Shidae Ilbo was founded by Choe Nam-seon in 1924; by 1936 this went by the name JoongAng Ilbo. [57] [10] These three Korean-language papers went on to be significant during the colonial period, [10] and were seen as a center for writers and literature. [58]

However, Japanese-language newspapers still held a position of prominence in Korea. From 1929 to 1939, the number of Japanese-language newspapers with a circulation of over 500 increased from 11 with a total of 102,707 copies to 17 with a total of 195,767 copies. Koreans began subscribing to the papers in increasing numbers; during that same period, the circulation for Korean subscribers to those papers increased around seven-fold (5,062 to 36,391). [59]

One Province, One Company and prohibitions

WIth the beginning of the Pacific War, the Japanese government made sweeping changes in both Japan and Korea. Beginning in January 1940, it executed a policy towards newspapers that has been dubbed "One Province, One Company" (1道1社; 1도 1사) or "One Province, One Paper" (1道1紙; 1도 1지). [10] [60] Under this policy, both Japanese- and Korean-language newspapers were merged or closed. [60] Chōsen Jihō was merged into the Fuzan Nippō, [61] and Chōsen Shinbun was merged into the Keijō Nippō. [62]

| Area | Newspaper |

|---|---|

| Keijō Nippō | |

| Chōsen Shōkō Shinbun | |

| Chūseinan-dō | Chūsen Nippō |

| Zenranan-dō | Zennan Shinpō |

| Zenrahoku-dō | Zenhoku Shinpō |

| Busan | Fuzan Nippō |

| Daegu | Taikyū Nichi Nichi Shinbun |

| Pyongyang | Heijō Nichi Nichi Shinbun |

| Heianhoku-dō | Ōkō Nippō |

| Kōkai-dō | Kōkai Nippo |

| Kōgen-dō | Hokusen Nichi Nichi Shinbun |

| Kankyōhoku-dō | Seishin Nippō |

The major Korean-owned newspapers, The Chosun Ilbo and The Dong-A Ilbo were shut down around this time. Kang Jun-man argued that this was done out of an abundance of caution and to accelerate Korea's assimilation. [64]

The One Province, One Company policy, as well as increasing restrictions on the learning and use of the Korean language, [65] contributed to significant consolidation in the newspaper market. The only major daily Korean-language newspaper that was allowed to continue publishing was the Maeil Sinbo, and it came to financially thrive. [66] Korean readers subscribed to Japanese newspapers in increasing numbers, with the Keijō Shinpō reportedly coming to have around 60% Korean subscribers during this period. [67]

End of the war and the colonial period

Despite the tide of World War II turning against Japan, newspapers in Korea attempted to highlight Japan's victories. Paper shortages began to affect newspapers, and many of them reduced their sizes and page counts. Fewer and fewer advertisements were published; some of the last remaining advertisements were often for the theater or for medical treatments. [68]

On August 6, the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. The Maeil Sinmun and Keijō Nippō mentioned the bombing on the August 8 edition, but did not prominently mention it or describe it in detail. One such headline read: "Enemy uses 'new bomb', causes significant damage to Hiroshima". [a] Around this time, the Japanese government prevented the press from using the term "atomic bomb" (原子爆弾; 원자폭탄). The following day, the Maeil Sinmun announced that the Korean prince Yi U had died "in battle"; in actuality he had been killed while commuting to work during the atomic bombing. At 12 p.m. on the 15th, the announcement of Japan's surrender was broadcast on the radio. The Maeil Sinmun and Keijō Nippō already had articles written and prepared for the announcement of the surrender. They were informed the evening before of the announcement, and published their articles soon afterwards. [68]

1945–1960: Korean independence

Since Korea's independence from Japan's rule, numerous periodicals, including newspapers and magazines, have emerged in response to media oppression.

The media was divided into left and right wing factions. [69]

Left-right confrontational press

The left-wing group took the lead in the press by first taking control of the facilities for printing newspapers. The leading left-wing newspapers were The Chosun Ilbo and the Liberation Daily. [70]

Founded on September 8, 1945, The Chosun Ilbo was founded by Korean employees working in the Keijō Nippō, which was first published by Kim Jeong-do, but in late October, Hong Jeung-sik, a prominent figure in the left-wing media community, changed to editor-in-chief and publisher. [71]

The number of printing facilities immediately after Korea's liberation from Japanese rule was very small as most of them belonged to the Japanese. The Communist Party of Korea not only received the Gonozawa Printing Office in Sogong-dong, Seoul, which was the best facility at the time, but also recruited the publishing labor union. [72]

The Chosun Ilbo was the first daily newspaper in Seoul after the August 15 Liberation, and on September 8, left-wing reporters from the Keijō Nippō, the official newspaper of the Japanese Government-General of Korea, were founded as tabloid Korean newspapers. [73]

The Liberation Daily was founded in 1945 by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Korea in Seoul. [74]

1960–1980: Military government

After May 16, 1961, the military government conducted a complete overhaul of newspapers and news agencies. [75] A year later, the military government strongly pushed ahead with its media policy to reform the structure of the media, announcing a 25-point "press policy" and "press policy implementation standards". [75] The Dong-A and Chosun incident occurred due to the intervention of government authorities, the press freedom protection movement, the suppression of advertisements, and labor-management conflicts. [75]

Incidents

On the surface, it was a conflict between the reporters and management of the two leading newspapers, Dong-A Ilbo and Chosun Ilbo. [76] However, the incidents revealed problems faced by the media, such as the dismissal of a large number of journalists in the 1970s, as well as the discord between journalists and business owners. [76]

Dong-A Ilbo incident

The incident started directly with the union formation of reporters. [77] On March 7, 1974, 33 reporters from the Dong-A Ilbo formed the Dong-A Ilbo Branch of the National Publishing Workers' Union. [77] However, the company began to fire the reporters that supported Dong-A Ilbo's traditional policy of not recognizing labor unions. [77] In protest, the union filed a lawsuit, which led to conflicts and more complex legal battles. In the midst of such labor-management conflicts, the Dong-A Ilbo dismissed and suspended reporters between March 10 and April 1975, forcing 134 reporters, producers, and announcers to leave the company. [77]

The Chosun Ilbo incident

At the same time, The Chosun Ilbo dismissed two journalists for "infringing their editorial rights". [77] 58 journalists were then later dismissed or suspended indefinitely by the end of March 1975 due to worsening conflicts between management and reporters, with 33 reporters dismissed as they canceled disciplinary action. [77]

Media integration and abandoned incident

In 1980, the consolidation of newspapers, broadcasting, and telecommunications had all taken place under the leadership of the new military. [78] Jun Doo-hwan's forces, which seized power due to the December 12 incident[ clarification needed], established a press team led by Lee Sang-jae at the intelligence office of the security company in early 1980, merged media companies to control the media essential to the power struggle, and dismissed journalists who were resistant or critical of the military's position. [78] The reason for the merger was that media companies became insolvent and a hotbed of corruption due to the turmoil of the media organizations. The voluntary closure or consolidation was a formality that was led by the New Military Department's security division. [78] The new military, including Jun, was found to be part of a ruling scenario in which the government forcibly merged media outlets such as newspapers, broadcasters, and news agencies under the guise of improving the structure of the media to complete the rebellion of the new military forces. [79]

Notes

- ^ 적(敵) 신형 폭탄 사용/ 광도시(廣島市)에 상당한 피해

References

- ^ a b "『조선 신보』(朝鮮新報)". 부산역사문화대전. Retrieved 2023-10-05.

- ^ a b 박 1998, pp. 111–112.

- ^ a b Altman (1984), p. 687.

- ^ Altman (1984), p. 685.

- ^ 박 1998, pp. 112–113.

- ^ a b c "한성순보(漢城旬報)" [Hansong Sunbo]. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-02-09.

- ^ a b "박문국의 설치와≪한성순보≫·≪한성주보≫의 간행". 우리역사넷 (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-02-09.

- ^ 정 2013, p. 26.

- ^ a b 정 2013, p. 33.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x 정, 진석; 최, 진우. "신문 (新聞)". Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Academy of Korean Studies. Retrieved 2024-02-11.

- ^ a b c d e f g "한성신보 (漢城新報)" [Kanjō Shinpō]. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-01-29.

- ^ a b c Orbach 2016, p. 113.

- ^ a b c 박 1998, p. 113.

- ^ a b c 박 1998, pp. 113–114.

- ^ 박 1998, pp. 113–114, 119.

- ^ a b 박 1998, p. 119.

- ^ Orbach 2016, pp. 113, 127.

- ^ 박 1998, p. 109–110.

- ^ Orbach 2016, p. 115.

- ^ a b "한성신보" [Kanjō Shinpō]. 우리역사넷. National Institute of Korean History. Retrieved 2024-01-29.

- ^ "경성신문(京城新聞)". Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-02-03.

- ^ "제국신문 (帝國新聞)". Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ "협성회회보 (協成會會報)". Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ 박, 정규. "황성신문 (皇城新聞)" [Hwangsŏng Sinmun]. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ "매일신문 (每日新聞)" [Maeil Sinmun]. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ a b c 정, 은령 (2001-09-18). "국내 최초 언론법 '대한제국 신문지 조례'제정 배경". The Dong-a Ilbo (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-02-12.

- ^ a b 하 2017, pp. 163–164.

- ^ 하 2017, pp. 165–166.

- ^ 박 1998, pp. 110–111.

- ^ 박 1998, p. 118.

- ^ 박 1998, p. 132.

- ^ a b c d e O'Connor 2010, p. 33.

- ^ a b 박 1998, p. 123.

- ^ 이, 태한 (2019-10-02). "'다사다난'한 전북언론, 그 역사를 알아보다" [Learn About the 'Eventful' Press of North Jeolla]. 전북대학교 신문방송사 (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-02-07.

- ^ 박 1998, p. 125.

- ^ "Chūsen Nippō — Browse by title — Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection". hojishinbun.hoover.org. Retrieved 2024-02-09.

- ^ a b 박 1998, p. 131.

- ^ 박 1998, p. 126.

- ^ 박 1998, pp. 125–127.

- ^ 박 1998, p. 128.

- ^ 박 1998, pp. 128–129.

- ^ 박 1998, p. 133.

- ^ 박 1998, p. 134.

- ^ 박 1998, pp. 132–133.

- ^ a b c Neff, Robert (2 May 2010). "UK journalist Bethell established newspapers in 1904". The Korea Times. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ a b c Han, Jeon (June 2019). "Fighting Injustice with the Pen". Korean Culture and Information Service. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ "서울프레스" [The Seoul Press]. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-01-29.

- ^ "한성신보(漢城新報)". Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-01-26.

- ^ Lent, John A. (February 1968). "History of the Japanese Press". Gazette (Leiden, Netherlands). 14 (1): 25. doi: 10.1177/001654926801400102. ISSN 0016-5492. S2CID 145644698.

- ^ "Keijō Nippō — 新聞名で閲覧 — 邦字新聞デジタル・コレクション". hojishinbun.hoover.org. Retrieved 2024-01-26.

- ^ 정 2013, pp. 78–79.

- ^ a b c d 박, 도준 (2019-10-14). "[창간특집] 우리는 언제나 역사의 편에 선다". Gyeongnam Ilbo (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-02-10.

- ^ a b c d e "경남일보(慶南日報)". Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-02-10.

- ^ a b c d 김, 덕영. "경남일보[慶南日報]". Korean Newspaper Archive. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ a b 강 2019, p. 107.

- ^ a b "3·1운동 (三一運動)". Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-02-12.

- ^ a b 정 2013, p. 50.

- ^ 정 2013, p. 51.

- ^ 강 2019, p. 215.

- ^ a b 강 2019, pp. 207–208.

- ^ 김, 보영. "『조선 시보』(朝鮮時報) - 부산역사문화대전". busan.grandculture.net. Retrieved 2024-02-03.

- ^ 이, 명숙. "조선신문[朝鮮新聞]". Korean Newspaper Archive. Retrieved 2024-02-05.

- ^ 강 2019, p. 208.

- ^ 강 2019, pp. 208–209.

- ^ 강 2019, p. 214.

- ^ 강 2019, p. 212.

- ^ 강 2019, pp. 214–215.

- ^ a b 정, 진석 (2015-07-20). "신문으로 보는 1945년 해방 前後의 한국" [[70th Anniversary of the Liberation Special] Before and After Korea's 1945 Liberation, Seen Through Newspapers]. Monthly Chosun (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-02-15.

- ^ 정 2013, p. 104.

- ^ 정 2013, p. 84.

- ^ 정 2013, p. 85.

- ^ "해방일보의 내용". Encyclopedia of Korean Culture.

- ^ "조선인민보의 정의". Encyclopedia of Korean Culture.

- ^ "해방일보의 정의". Encyclopedia of Korean Culture.

- ^ a b c 정 2013, p. 93.

- ^ a b 정 2013, p. 97.

- ^ a b c d e f 정 2013, p. 98.

- ^ a b c "언론통폐합사건". Encyclopedia of Korean Culture.

- ^ "언론통폐합". Encyclopedia of Korean Local Culture.

Sources

- 강, 준만 (2019). 한국 언론사 [History of the Korean Press] (in Korean) (Google Play, original pages view ed.). 인물과사상사. ISBN 978-89-5906-530-1.

- 박, 용구 (1998). "구한말(1881~1910) 지방신문에 관한 연구" [Research on Joseon to Korean Empire (1881–1910) Local Newspapers] (PDF). 한국언론정보학보. 11. 한국언론정보학회: 108–140.

- 정, 진석 (2013). 한국 신문 역사 [The History of Korean Newspapers]. 커뮤니케이션북스. ISBN 9788966801848.

- 하, 지연 (2017-09-25). 기쿠치 겐조, 한국사를 유린하다 (in Korean). 서해문집. ISBN 978-89-7483-874-4.

- Altman, Albert A. (1984). "Korea's First Newspaper: The Japanese Chōsen shinpō". The Journal of Asian Studies. 43 (4): 685–696. doi: 10.2307/2057150. ISSN 0021-9118. JSTOR 2057150. S2CID 154966097.

- O'Connor, Peter (2010-09-01). The English-language Press Networks of East Asia, 1918-1945. Global Oriental. ISBN 978-90-04-21290-9.

- Orbach, Danny (2016). Curse on This Country: The Rebellious Army of Imperial Japan. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-0834-3.