The history of Socotra describes the cultures, events, peoples and strategic relevance for sea trade of what is Socotra, an island of the Republic of Yemen, currently under control of the United Arab Emirates (UAE)-backed Southern Transitional Council, a secessionist participant in Yemen's ongoing civil war. [1] Lying between the Guardafui Channel and the Arabian Sea and near major shipping routes, Socotra is the largest of the four islands in the Socotra archipelago.

Etymology

Scholars don't agree about the origin of the name of the island. After that the name Socotra may derive from:

- A Greek term derived from the name of a South Arabian tribe mentioned in Sabaic and Ḥaḑramitic inscriptions as Dhū-Śakūrid (S³krd). [2]

- The Greek name Dioskouridon nēsos (Διοσκουρίδων νῆσος) meaning "the island of the Dioscuri". [3]

- The Arabic term Suqutra broken down as follows: Suq, means market, and qutra is a vulgar form of qatir, which refers to dragon's blood. Indeed, the capital city of Socotra was Suq as reported by the Portuguese in the 16th century, which they referred to as market place. [4]

Prehistory

Socotra was inhabited around 2,000 to 4,000 years ago.

Ancient history

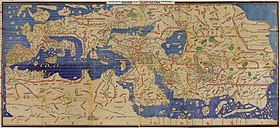

By the turn of the Common Era, Socotra was a crossroad of commerce based on the monsoon winds. This sea trade brought together people from the coasts of western Indian Ocean, Red Sea and East-Africa, [5] as well as the Mediterranean. Socotra contributed to this sea trade with tortoise shells and resins of Myrrh, Frankincense and dragon tree, highly prized as fragrant incense and widely used in medicine and cosmetics. [6]

But as per the fourth century, demand for the resins declined giving way to a cattle-breeding economy organized in pastoral tribes. [7]

Written sources

In the late 2nd century BCE, Agatharchides recorded merchants from Potana, coming to the "Blessed Islands" (Socotra) to trade with Alexandrian merchants. [8]

The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a first-century CE Greek navigation aid describes Socotra as follows:

The inhabitants, few in number, live on one side of the island, that to the north, the part facing the mainland; they are settlers, a mixture of Arabs and Indians and even some Greeks, who sail out of there to trade.

— Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, §30 [9]

[The island was] subject to the King of the frankincense-bearing land [i.e. the Kingdom of Hadhramaut].

— Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, §31 [10]

The Weilüe, a Chinese historical text written in the third century CE states:

The king of Zesan (Socotra) is subject to Da Qin (Rome). His seat of government is in the middle of the sea… [Zesan] is in close communication with Angu city ( Gerrha) in Anxi ( Parthia). [11]

Petroglyph sites

- The Eriosh Petroglyphs, located on the north coast 20 km south-west of the capital Hadibu, contain petroglyphs depicting figures of men, camels, foot symbology and crosses of uncertain dating. [12] [13]

- In the outskirts of Suq 2.5 km west of Hadibu there is a petroglyph site containing cruciform shaped, plant-like, and foot symbology. [12]

- Hoq Cave, situated on the north-eastern coast of the island, contains a large number of inscriptions, drawings and archaeological objects. [12] Investigation showed that these had been left by sailors who visited the island between the first century BCE and the sixth century CE. Texts are written in Indian Brāhmī, South Arabian, Ethiopic, Greek, Palmyrene and Bactrian scripts and languages. This corpus of nearly 250 texts and drawings constitutes one of the main sources for the investigation of Indian Ocean trade networks in that time period, [14] indicating the diverse origins of those who used Socotra as a trading base in antiquity. [15]

- The Dahaisi Cave, located in the eastern interior of the island on the Momi Plateau, contains pictograms of cruciform and geometric patterns, Arabic inscriptions as well as zoomorphic figures attributed to between the first century BCE and the fifteen century CE. [12] [16]

Medieval History

The earliest account concerning the presence of Christians in Socotra stems from the 6th century CE Greek merchant Cosmas Indicopleustes, [12] who holds that there were - still Greek speaking - colonists on the island once settled by the Ptolemies. [17]

In 880, an Ethiopian expeditionary force conquered the island and an Oriental Orthodox bishop was consecrated. The Ethiopians were later dislodged by an armada sent by Imam Al-Salt bin Malik of Oman. [18] [19]

In his Geography of the Arabian Peninsula (Sifat Jazirat ul-Arab), Abu Muhammad al-Hasan al-Hamdani (893 – 945) describes the geography and the linguistic situation of the Arabian peninsula and Socotra stating, that Alexander the Great sent Greeks to Socotra to cultivate the endemic aloe. [20]

The geographer Yaqut al-Hamawi (1179–1229) writes: "Whoever is bound for the Land of the Zanj sails past Socotra. The majority of its population are Christian Arabs. Thence are delivered aloe and the resin of a tree which grows only on this island." [7]

The Persian geographer Ibn al-Mujawir (1204-1291) shed much light on the culture and everyday life of the Socotrans giving clues to their ancient religious beliefs, particularly in the references to good and evil jinns. He reported that there were two groups of people on the island, the indigenous mountain dwellers and the foreign coastal dwellers. [21]

Socotra is also mentioned in the Travels of Marco Polo. Although Marco Polo did not pass anywhere near the island, he reports that "the inhabitants are baptized Christians and have an archbishop", who "has nothing to do with the Pope in Rome, but is subject to an archbishop who lives at Baghdad”. [22] Prior to Marco Polo, in the 10th century, the Arabic geographer Al-Masudi noted that Socotra was at that time a pirate base: “Let me tell you further that many corsairs put in at this island at the end of a cruise and pitch camp here and sell their booty". [23]

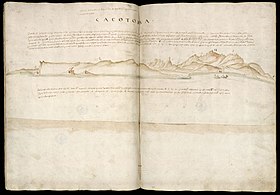

In 1507, a Portuguese fleet commanded by Tristão da Cunha with Afonso de Albuquerque landed at the then capital of Suq and captured its port after a stiff battle against the Mahra Sultanate. Their objective was to set a base in a strategic place on the route to India. The infertility of the land led the Portuguese abandon the island in 1511. [24] The island reverted to the control of the Mahra Sultanate, and the inhabitants converted to Islam. [25]

Modern era

In 1834, the East India Company stationed a garrison on Socotra in the expectation that the Mahra sultan of Qishn and Socotra, who resided at Qishn on the mainland, would accept an offer to sell the island. The lack of good anchorages proved to be as much a problem for the British as the Portuguese, and there was nowhere for a coaling station to be used by the new steamship line on the Suez-Bombay route. Faced with the unexpected firm refusal of the sultan to sell, the British left in 1835. After the capture of Aden in 1839, they lost all interest in acquiring Socotra for now.

In January 1876, in exchange for a payment of 3,000 thalers and a yearly subsidy, the sultan pledged "himself, his heirs and successors, never to cede, to sell, to mortgage, or otherwise give for occupation, save to the British Government, the Island of Socotra or any of its dependencies." Additionally, he pledged to assist any European vessel that wrecked on the island and protect the crew, the passengers and the cargo, in exchange for a suitable reward. [27]

In April 1886, the British government concluded a protectorate treaty with the sultan in which he promised this time to "refrain from entering into any correspondence, agreement, or treaty with any foreign nation or power, except with the knowledge and sanction of the British Government", and give immediate notice to the British Resident at Aden of any attempt by another power to interfere with Socotra and its dependencies. [28] Apart from those obligations, this preemptive protectorate treaty, designed above all to seal off Socotra against competition from other colonial powers, however, left the sultan in control of the island.

In 1897, the P&O ship Aden sank after being wrecked on a reef near Socotra, with the loss of 78 lives. As some of the cargo had been plundered by islanders, the sultan was reminded of his obligations under the agreement of 1876. [29]

The Sultanate of Mahra disposed of two main revenue sources in Socotra:

- The British annual payment of protectorate fees.

- Taxation of the by-products (e.g. ghee, dates) of a transhumant subsistence pastoralism with herds of goat, sheep, cow, and camel, fishing or date farming in a nearly cashless, and thus barter economy. [30]

20th century and beyond

In October 1967, in the wake of the departure of the British from Aden and southern Arabia, the Mahra Sultanate was abolished. On 30 November of the same year, Socotra became part of South Yemen. Since Yemeni unification in 1990, Socotra has been a part of the Republic of Yemen.

Socotra was raged by the 26 December 2004 tsunami causing a child dead and 40 fishing boats wrecked although the island is 4,600 km (2,858 mi) far away from tsunami epicentre off the west coast of Aceh, Indonesia. [31]

In 2015, the cyclones Chapala and Megh struck the island, causing severe damage to its infrastructure.

From 2016 onwards Socotra is under the de facto control of the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council, a secessionist participant in Yemen's ongoing civil war. [32]

References

- ^ "Yemen's Socotra, isolated island at strategic crossroads". The Economic Times. 7 June 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

-

^

"Cambridge Scholars Publishing. Ancient South Arabia through History". www.cambridgescholars.com. pp. 5–6. Retrieved 2020-02-20.

As for Śakūrid (S³krd), this name appears to be the basis of the Greek name for Soqoṭra, Dioskouridēs, via a reconstructed *Dhū-Śakūrid.12

. - ^ Great Britain. Naval Intelligence Division (2005). "Appendix: Socotra". Western Arabia and the Red Sea. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. p. 611. ISBN 9781136209956.

- ^ A Historical Genealogy of Socotra as an Object of Mythical Speculation, Scientific Research & Development Experiment Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ Seland, Eivind (2014). "Archaeology of Trade in the Western Indian Ocean, 300 BC–AD 700". Journal of Archaeological Research. 22 (4): 367–402. doi: 10.1007/s10814-014-9075-7. hdl: 1956/8950. S2CID 254601669.

- ^ Grant, Grainne (2005). "Socotra: Hub of the Frankincense Trade". The UC Davis Undergraduate Research Journal. 8: 119–138.

- ^ a b Naumkin, Vitaly (1989). "Fieldwork in Socotra". Bulletin of the British Society for Middle Eastern Studies. 16 (2): 133–142. doi: 10.1080/13530198908705493.

- ^ Agatharchides of Cnidus, On the Erythraean Sea, translated and edited by Stanley M. Burstein (London, Hakluyt Society, 1989), p. 169.

- ^ Schoff (1912), §30.

- ^ Schoff (1912), §31.

- ^ The Peoples of the West Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Jansen van Rensburg, Julian (2018). "Rock Art of Soqotra, Yemen: A Forgotten Heritage Revisited". The Artist and Journal of Home Culture. 7: 99.

- ^ Naumkin, Vitaly; Sedov, Alexandr (1993). "Monuments of Socotra". Topoi. 70 (2): 569–623. doi: 10.3406/topoi.1993.1486.

- ^ Bukharin, Mikhail D.; De Geest, Peter; Dridi, Hédi; Gorea, Maria; Jansen Van Rensburg, Julian; Robin, Christian Julien; Shelat, Bharati; Sims-Williams, Nicholas; Strauch, Ingo (2012). Strauch, Ingo (ed.). Foreign Sailors on Socotra. The inscriptions and drawings from the cave Hoq. Bremen: Dr. Ute Hempen Verlag. p. 592. ISBN 978-3-934106-91-8.

- ^ Sidebotham, Steven E. (2011). Berenike and the Ancient Maritime Spice Route. California. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-520-24430-6.

- ^ Jansen van Rensburg, Julian (2018). "The rock art of Dahaisi cave, Soqotra, Yemen". Rock Art Research. 35.

- ^ Cohen (2006), p. 326.

- ^ Martin, E. G. (1974). "Mahdism and holy wars in Ethiopia before 1600". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 4: 114. JSTOR 41223140.

- ^ Missick, Stephen Andrew (12 April 2016). "Socotra: The Mysterious Island of the Assyrian Church of the East". Church of Beth Kokheh Journal. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ^ Republic of Yemen, Socotra Archipelago, Proposal for inclusion in the World Heritage List - UNESCO, January 2006.

- ^ Smith, Rex (1985). "Ibn al-Mujāwir on Dhofar and Socotra". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 15.

- ^ Polo, Marco (1958). The Travels of Marco Polo. Translated and introduction by Ronald Latham. Penguin Books. pp. 296–297. ISBN 978-0-14-044057-7.

- ^ Doe, Brian (1992). Socotra Island of Tranquility. pp. 136–137. ISBN 978-0907151319.

- ^ Diffie, Bailey Wallys; Winius, George Davison (1977). Foundations of the Portuguese empire, 1415–1580. University of Minnesota Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-8166-0782-2.

- ^ Bowersock, Glen Warren; Brown, Peter; Grabar, Oleg (1999). Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World. Harvard University Press. p. 753. ISBN 978-0674511736.

- ^ From The Isle of Frankincense by Charles K. Moser, formerly United States Consul-General to Aden, Arabia. Page 271 in The National Geographic Magazine, January to June 1918, Vol. XXXIII, 266-278.

- ^ Aitchison (1876), p. 181-192.

- ^ Aitchison (1876), p. 185.

- ^ Aitchison (1876), p. 72.

- ^ Elie, Serge D. (2008). "The Waning of Soqotra's Pastoral Community: Political Incorporation as Social Transformation". Human Organization. 67 (3): 335–345. doi: 10.17730/humo.67.3.lm86541uv4765823.

- ^ Hermann M. Fritz; Emile A. Okal (2008). "Socotra Island, Yemen: field survey of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami". Natural Hazards. 46 (1): 107–117. Bibcode: 2008NatHa..46..107F. doi: 10.1007/s11069-007-9185-3. S2CID 14199971.

- ^ "Yemen's Socotra, isolated island at strategic crossroads". The Economic Times. 7 June 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

Works cited

- Schoff, Wilfred Harvey, ed. (1912), The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century, New York: Longmans, Green, & Co., ISBN 978-81-215-0699-1.

- Cohen, Getzel (2006), The Hellenistic Settlements in Syria, the Red Sea Basin, and North Africa, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-24148-0, JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctt1pnd22.

- Aitchison, C. U. (1876). "A Collection of Treaties, Engagements and Sunnuds related to India and Neighboring Countries". Calcutta. VII..