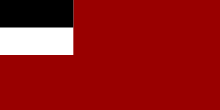

Flag of DRG | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | March 18, 1921 |

| Dissolved | 1954 |

| Headquarters | Leuville-sur-Orge, France |

| Agency executive |

|

After the Soviet Russian Red Army invaded Georgia and the Bolsheviks conquered the country early in 1921, the Parliament of the Democratic Republic of Georgia (DRG) decided that the Government should go into exile and continue to function as the National Government of Georgia (NGG).

History

Exile to France

After the war with the Soviets was irreversibly lost, the Constituent Assembly of Georgia, managed by Karlo Chkheidze, [1] at its last session in Batumi on 18 March 1921, decided on the exile of the Georgian Social Democratic (Menshevik) Party government, managed by Noe Zhordania. [2] On the same day, the members of the government, several deputies of the Constituent Assembly of Georgia, a few military officers and their families went aboard the ship Ernest Renan and sailed first to Istanbul, Turkey, and then to France, the government of which granted the Georgian émigrés political asylum.

1924 Uprising preparation

Using Georgian state funds, the government bought a 5-hectare (12-acre) domain surrounding a small château in Leuville-sur-Orge, a town located near Paris. Leuville was declared an official residence of the government in exile. Although the émigrés experienced a permanent shortage of money, Zhordania's government maintained relations with the still popular Georgian Social Democratic (Menshevik) Party and other anti-Soviet organizations in Georgia, and thus constituted a nuisance to the Soviet authorities. The NGG encouraged and helped the Committee for Independence of Georgia, an inter-party bloc in Georgia, in its struggle against the Bolshevik regime, which culminated in the 1924 August Uprising. Prior to the revolt, Noe Khomeriki, [3] the Minister of Agriculture in exile, Benia Chkhikvishvili, [4] the former mayor of Tbilisi, and Valiko Jugheli, [5] the former commander of the People’s Guard, returned secretly to Georgia, but were arrested and executed soon thereafter by the Soviet secret police, the Cheka.

International attention on Georgia

The NGG attempted to bring Georgian affairs to international attention on numerous occasions. Several memoranda urging assistance for the cause of Georgian independence were sent to the British, French, and Italian governments as well as to the League of Nations, which adopted two resolutions, in 1922 and 1924, endorsing Georgia's sovereignty. Generally, however, the world largely neglected the violent Soviet conquest of Georgia. On 27 March 1921, the exiled Georgian government issued an appeal from their temporary offices in Istanbul to "all socialist parties and workers' organizations" of the world, protesting against the invasion of Georgia. The appeal was unheeded, though. Beyond passionate editorials in some Western newspapers and pleas for action from such Georgian sympathizers as Sir Oliver Wardrop, the international response to the events in Georgia was subdued. [6]

Death of Karlo Chkheidze and Noe Ramishvili

The Georgian émigrés' hopes that the Great Powers intended to help had begun to subside. A loss was sustained by the Georgian émigrés when Karlo Chkheidze committed suicide [7] in 1926 and Noe Ramishvili, [8] the most energetic Georgian émigré politician and president of the first government of Democratic Republic of Georgia, was assassinated by a Bolshevik spy in 1930.

Soviet infiltration of Georgian government-in-exile

The Soviet intelligence managed to infiltrate the exiled government, due largely to Lavrentiy Beria's personal intelligence network, both before and after the Second World War.

Politics

Diplomatic recognition

With the emigration of Zhordania's government and the establishment of the Georgian SSR, the question of recognition was considered by the foreign states that had recognized de jure the independence of Georgia before the Soviet conquest. Some countries, particularly Liberia and Mexico, recognized the DRG when its government was already in exile, on 28 March 1921 and 12 May 1921, respectively. The NGG continued to be recognized for some time as "the legitimate Government of Georgia" by Belgium, the United Kingdom, France and Poland. [9] The NGG was able to maintain a legation in Paris until 1933 (chaired by Sosipatre Asatiani [10]), when it was closed as a result of the Franco-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact of 29 November 1932. The NGG and its chief ally in Europe, the International Committee for Georgia, the president of which was Jean Martin, director of Journal de Genève, later began a campaign against the admission of the USSR into the League of Nations, which nevertheless occurred during September 1934, decreasing even more the effectiveness of the NGG. [11]

Heads of the National Government of Georgia in exile

- 1921–1953 — Noe Zhordania (1868–1953)

- 1953–1954 — Evgeni Gegechkori (1881–1954)

See also

- Georgian emigration in Poland

- (French) Ière République en exil Archived 2007-03-12 at the Wayback Machine

References

- ^ (French) Nicolas Tchkhéidzé, Président of l'Assemblée constituante Archived 2018-08-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ (French) Noé Jordania, Président des second et troisième gouvernements Archived 2018-08-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ (French) Noe Khomeriki, ancien ministre de l'Agriculture.

- ^ (French) Benia Chkhikvishvili, ancien maire de Tbilissi.

- ^ (French) Valiko Jugheli, ancien commandant de la Garde populaire.

- ^ King, Charles (2008), The Ghost of Freedom: A History of the Caucasus, p. 173. Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-517775-4.

- ^ Georgian government in exile, Karlo Chkheidze's burial.

- ^ (French) Noe Ramishvili, President of the first Government Archived 2019-05-25 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Stefan Talmon (1998), Recognition of Governments in International Law, p. 289-290. Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-826573-5.

- ^ (French) Sosipatre Asatiani, premier secrétaire de la Légation géorgienne à Paris Archived 2019-01-24 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ David Marshall Lang (1962). A Modern History of Georgia, p. 258. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.