| Fatigue | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Exhaustion, weariness, tiredness, lethargy, listlessness |

| |

| Specialty |

Primary care

|

| Treatment | Avoid known stressors and unhealthy habits ( drug use, excessive alcohol consumption, smoking), healthy diet, exercise regularly, medication, hydration, and vitamins |

Fatigue describes a state of tiredness (which is not sleepiness), exhaustion [1] or loss of energy. [2] [3]

In general usage, fatigue often follows prolonged physical or mental activity. When fatigue occurs independently of physical or mental exertion, or does not resolve after rest or sleep, it may have other causes, such as a medical condition. [4]

Fatigue (in the medical sense) is associated with a wide variety of conditions including autoimmune disease, organ failure, chronic pain conditions, mood disorders, heart disease, infectious diseases, and post-infectious-disease states. [5] However fatigue is complex and in up to a third of primary care cases no medical or psychiatric diagnosis is found. [6] [7] [8]

Fatigue (in the general usage sense of normal tiredness) can include both physical and mental fatigue. Physical fatigue results from muscle fatigue brought about by intense physical activity. [9] [10] [11] Mental fatigue results from prolonged periods of cognitive activity which impairs cognitive ability. Mental fatigue can manifest as sleepiness, lethargy, or directed attention fatigue, [12] and can also impair physical performance. [13]

Definition

Fatigue in a medical context is used to cover experiences of low energy that are not caused by normal life. [2] [3]

A 2021 review proposed a definition for fatigue as a starting point for discussion: "A multi-dimensional phenomenon in which the biophysiological, cognitive, motivational and emotional state of the body is affected resulting in significant impairment of the individual's ability to function in their normal capacity". [14]

Another definition is that fatigue is "a significant subjective sensation of weariness, increasing sense of effort, mismatch between effort expended and actual performance, or exhaustion independent from medications, chronic pain, physical deconditioning, anaemia, respiratory dysfunction, depression, and sleep disorders". [15]

Terminology

The use of the term "fatigue" in medical contexts may carry inaccurate connotations from the more general usage of the same word. More accurate terminology may also be needed for variants within the umbrella term of fatigue. [16]

Comparison with other terms

Tiredness

Tiredness which is a normal result of work, mental stress, anxiety, overstimulation and understimulation, jet lag, active recreation, boredom, or lack of sleep is not considered medical fatigue. This is the tiredness described in MeSH Descriptor Data. [17]

Sleepiness

Sleepiness refers to a tendency to fall asleep, whereas fatigue refers to an overwhelming sense of tiredness, lack of energy, and a feeling of exhaustion. Sleepiness and fatigue often coexist as a consequence of sleep deprivation. [18] However sleepiness and fatigue may not correlate. [19] Fatigue is generally considered a longer-term condition than sleepiness (somnolence). [20]

Features

Common features

Distinguishing features of medical fatigue include

- unpredictability,

- not linking fatigue to an obvious cause, such as a physical exertion,

- variability in severity,

- fatigue being relatively profound/overwhelming, and having extensive impact on daily living,

- lack of improvement with rest,

- where an underlying disease is present, the quantum of fatigue often does not correlate with the severity of the underlying disease. [14] [21] [22] [23]

Characteristics by cause

Differentiating characteristics of fatigue that may help identify the possible cause of fatigue include

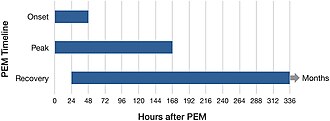

- Post-exertional malaise; a common feature of ME/CFS fatigue, [24] but not a feature of other fatigues.

- Increased by heat or cold; MS fatigue is in many cases effected in this way. [25] [26]

- Remission; MS fatigue may reduce during periods of other MS symptom remission. [27] [28] ME/CFS may also have lower periods of activity. [29]

- Cognitive declines; sleep deprivation causes cognitive and neurobehavioral effects including unstable attention and slowing of response times. [30] ME/CFS and MS may cause brain fog over longer timescales.

- Intermittency; Fatigues often vary in how and when they occur. Some fatigues (RA, cancer fatigue [31]) seem to often be continual (24/7) whilst others (MS, Sjögren's, lupus, brain injury [32]) are often intermittent. [33] A 2010 study found that Sjögren's patients reported fatigue after rising, an improvement in mid-morning, and worsening later in the day, whereas lupus (SLE) patients reported lower fatigue after rising followed by increasing fatigue through the day. [34] ME/CFS symptoms can be continual, or can fluctuate during the day, from day to day, and over longer periods. [29]

- The pace of onset may be a related differentiating factor; MS fatigue can have abrupt onset. [35]

Some people may have multiple causes of fatigue.

Classification

By type

Uni- or multi-dimensional

Fatigue can be seen as a uni-dimensional phenomenon that influences different aspects of human life. [36] [37] It can be multi-faceted and broadly defined, making understanding the causes of its manifestations especially difficult in conditions with diverse pathology including autoimmune diseases. [38]

A 2021 review considered that different "types/subsets" of fatigue may exist and that patients normally present with more than one such "type/subset". These different "types/subsets" of fatigue may be different dimensions of the same symptom, and the relative manifestations of each may depend on the relative contribution of different mechanisms. Inflammation may be the root causal mechanism in many cases. [14]

Physical

Physical fatigue, or muscle fatigue, is the temporary physical inability of muscles to perform optimally. The onset of muscle fatigue during physical activity is gradual, and depends upon an individual's level of physical fitness – other factors include sleep deprivation and overall health. [39] Physical fatigue can be caused by a lack of energy in the muscle, by a decrease of the efficiency of the neuromuscular junction or by a reduction of the drive originating from the central nervous system, and can be reversed by rest. [40] The central component of fatigue is triggered by an increase of the level of serotonin in the central nervous system. [41] During motor activity, serotonin released in synapses that contact motor neurons promotes muscle contraction. [42] During high level of motor activity, the amount of serotonin released increases and a spillover occurs. Serotonin binds to extrasynaptic receptors located on the axonal initial segment of motor neurons with the result that nerve impulse initiation and thereby muscle contraction are inhibited. [43]

Muscle strength testing can be used to determine the presence of a neuromuscular disease, but cannot determine its cause. Additional testing, such as electromyography, can provide diagnostic information, but information gained from muscle strength testing alone is not enough to diagnose most neuromuscular disorders. [44]

Mental

Mental fatigue is a temporary inability to maintain optimal cognitive performance. The onset of mental fatigue during any cognitive activity is gradual, and depends upon an individual's cognitive ability, and also upon other factors, such as sleep deprivation and overall health.

Mental fatigue has also been shown to decrease physical performance. [12] It can manifest as somnolence, lethargy, directed attention fatigue, or disengagement. Research also suggests that mental fatigue is closely linked to the concept of ego depletion, though the validity of the concept is disputed. For example, one pre-registered study of 686 participants found that after exerting mental effort, people are likely to disengage and become less interested in exerting further effort. [45]

Decreased attention can also be described as a more or less decreased level of consciousness. [46] In any case, this can be dangerous when performing tasks that require constant concentration, such as operating large vehicles. For instance, a person who is sufficiently somnolent may experience microsleep. However, objective cognitive testing can be used to differentiate the neurocognitive deficits of brain disease from those attributable to tiredness. [47] [48] [49]

The perception of mental fatigue is believed to be modulated by the brain's reticular activating system (RAS). [50] [51] [52] [53] [54]

Fatigue impacts a driver's reaction time, awareness of hazards around them and their attention. Drowsy drivers are three times more likely to be involved in a car crash, and being awake over 20 hours is the equivalent of driving with a blood-alcohol concentration level of 0.08%. [55]

Neurological fatigue

People with multiple sclerosis experience a form of overwhelming tiredness that can occur at any time of the day, for any duration, and that does not necessarily recur in a recognizable pattern for any given patient, referred to as "neurological fatigue", and often as "multiple sclerosis fatigue" or "lassitude". [56] [57] [58]

People with autoimmune diseases including inflammatory rheumatic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and primary Sjögren's syndrome, experience similar fatigue. [14] [38] Attempts have been made to isolate causes of central nervous system fatigue.

By timescale

Acute

Acute fatigue is that which is temporary and self-limited. Acute fatigue is most often caused by an infection such as the common cold and can be cognized as one part of the sickness behavior response occurring when the immune system fights an infection. [59]

Other common causes of acute fatigue include depression and chemical causes, such as dehydration, poisoning, low blood sugar, or mineral or vitamin deficiencies.

Prolonged

Prolonged fatigue is a self-reported, persistent (constant) fatigue lasting at least one month. [60] [61]

Chronic

Chronic fatigue is a self-reported fatigue lasting at least 6 consecutive months. Chronic fatigue may be either persistent or relapsing. [62] Chronic fatigue is a symptom of many chronic illnesses and of idiopathic chronic fatigue.[ medical citation needed]

By effect

Fatigue can have significant negative impacts on quality of life. [63] [64] Profound and debilitating fatigue is the most common complaint reported among individuals with autoimmune disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, multiple sclerosis, type 1 diabetes, celiac disease, Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, and rheumatoid arthritis. [14]

Fatigue has been described by sufferers as 'incomprehensible' due to its unpredictable occurrence, lack of relationship to physical effort and different character as compared to tiredness. [65]

Fatigue that dissociates by quantum with disease activity represents a large health economic burden and unmet need to patients and to society. [14]

Formal classification

The World Health Organization's ICD-11 classification [66] includes a category MG22 Fatigue (typically fatigue following exertion but sometimes may occur in the absence of such exertion as a symptom of health conditions), and many other categories where fatigue is mentioned as a secondary result of other factors. [67] It does not include any fatigue-based psychiatric illness (unless it is accompanied by related psychiatric symptoms). [68] [69]

DSM-5 lists 'fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day' as one factor in diagnosing depression. [70]

Measurement

Fatigue is currently measured by many different self-measurement surveys. [71] One example is the Fatigue Severity Scale. [72] [73] [74] There is no consensus on best practice, [75] and the existing surveys do not capture the intermittent nature of some forms of fatigue.

Nintendo announced plans for a device to possibly quantitatively measure fatigue in 2014, [76] but the project was stopped in 2016. [77]

Causes

Unknown

In up to a third of fatigue primary care cases no medical or psychiatric diagnosis is found. [6] [7] [8] Tiredness is a common medically unexplained symptom. [7]

Sleep disturbance

Fatigue can often be traced to poor sleep habits. [78] Sleep deprivation and disruption is associated with subsequent fatigue. [79] [80] Sleep disturbances due to disease may impact fatigue. [81] [82]

Medications

Fatigue may be a side effect of certain medications (e.g., lithium salts, ciprofloxacin); beta blockers, which can induce exercise intolerance, medicines used to treat allergies or coughs [78]) and many cancer treatments, particularly chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Psychological stress and conditions

Adverse life events have been associated with fatigue. [14]

Association with diseases and illnesses

Fatigue is often associated with diseases and conditions. Some major categories of conditions that often list fatigue as a symptom include physical diseases, substance use illness, mental illnesses, and other diseases and conditions.

Physical diseases

- autoimmune diseases, [38] such as celiac disease, lupus, multiple sclerosis, [83] myasthenia gravis, NMOSD, Sjögren's syndrome, [34] rheumatoid arthritis, [84] [85] spondyloarthropathy and UCTD; [86] this population's primary concern is fatigue; [38] [87]

- blood disorders, such as anemia and hemochromatosis;[ medical citation needed]

- brain injury; [88] [89]

- cancer, in which case it is called cancer fatigue; [90]

- Covid-19 and long Covid; [91]

- developmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder; [92]

- endocrine diseases or metabolic disorders: diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism and Addison's disease; [93]

- fibromyalgia;[ medical citation needed]

- heart failure and heart attack; [94]

- HIV;[ medical citation needed]

- inborn errors of metabolism such as fructose malabsorption; [95] [96]

- infectious diseases such as infectious mononucleosis or tuberculosis; [93]

- irritable bowel syndrome;[ medical citation needed]

- kidney diseases, e.g., acute renal failure, chronic renal failure; [93]

- leukemia or lymphoma;[ medical citation needed]

- liver failure or liver diseases, e.g., hepatitis; [93] [22]

- Lyme disease;[ medical citation needed]

- neurological disorders such as narcolepsy, Parkinson's disease, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and post-concussion syndrome;[ medical citation needed]

- physical trauma and other pain-causing conditions, such as arthritis;[ medical citation needed]

- sleep deprivation or sleep disorders, e.g. sleep apnea; [93]

- stroke;[ medical citation needed]

- thyroid disease such as hypothyroidism;[ medical citation needed]

Substance use illnesses

- substance use disorders including alcohol use disorder; [97]

Mental illnesses

- anxiety disorders, such as generalized anxiety disorder; [98]

- depression; [99] [14]

- eating disorders, which can produce fatigue due to inadequate nutrition;[ medical citation needed]

- Gulf War syndrome;[ medical citation needed]

Other

- myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS); [97]

- idiopathic chronic fatigue, a term used to describe chronic fatigue which does not have symptoms of ME/CFS. [100] [101] However ICF does not have a dedicated diagnostic code in the World Health Organization's ICD-11 classification. [102]

Primary vs. secondary

In some areas it has been proposed that fatigue be separated into primary fatigue, caused directly by a disease process, and ordinary or secondary fatigue, caused by a range of causes including exertion and also secondary impacts on a person of having a disease (such as disrupted sleep). [103] [104] [105] [106] [107] [108] The ICD-11 MG22 definition of fatigue [109] captures both types of fatigue; it includes fatigue that "occur[s] in the absence of... exertion... as a symptom of health conditions."[ medical citation needed]

Obesity

Obesity correlates with higher fatigue levels and incidence. [110] [111] [112]

Drug use

Caffeine and alcohol can cause fatigue. [113]

Somatic symptom disorder

In somatic symptom disorder [114] the patient is overfocused on a physical symptom, such as fatigue, that may or may not be explained by a medical condition. [115] [116] [117]

Scientifically unsupported causes

The concept of adrenal fatigue is often raised in media but no scientific basis has been found for it. [118] [119] [120]

Mechanisms

The mechanisms that cause fatigue are not well understood. [38] Several mechanisms may be in operation within a patient, [121] with the relative contribution of each mechanism differing over time. [14]

Some mechanisms proposed as active in fatigue are inflammation, heat shock proteins and reduced brain connectivity.

Inflammation

Inflammation distorts neural chemistry, brain function and functional connectivity across a broad range of brain networks, [122] and has been linked to many types of fatigue. [38] [123] Findings implicate neuroinflammation in the etiology of fatigue in autoimmune and related disorders. [14] [38] Low-grade inflammation may cause an imbalance between energy availability and expenditure. [124]

Cytokines are small protein molecules that modulate immune responses and inflammation (as well as other functions) and may have causal roles in fatigue. [125] [126] However a 2019 review was inconclusive as to whether cytokines play any definitive role in ME/CFS. [127]

The inflammation model may have difficulty in explaining the "unpredictability" and "variability" (i.e. appearing intermittently during the day, and not on all days) of the fatigue associated with inflammatory rheumatic diseases and autoimmune diseases (such as multiple sclerosis). [14]

Heat shock proteins

A small 2016 study found that primary Sjögren's syndrome patients with high fatigue, when compared with those with low fatigue, had significantly higher plasma concentrations of HSP90α, and a tendency to higher concentrations of HSP72. [128] A small 2020 study of Crohn's disease patients found that higher fatigue visual analogue scale (fVAS) scores correlated with hgher HSP90α levels. [129] A related small 2012 trial investigating if application of an IL-1 receptor antagonist ( anakinra) would reduce fatigue in primary Sjögren's syndrome patients was inconclusive. [130] [131] [132]

Reduced brain connectivity

Fatigue has been correlated with reductions in structural and functional connectivity in the brain. [133] This has included in post-stroke, [134] MS, [135] NMOSD and MOG, [15] and ME/CFS. [136] This was also found for fatigue after brain injury, [137] including a significant linear correlation between self-reported fatigue and brain functional connectivity. [138]

Areas of the brain for which there is evidence of relation to fatigue are the thalamus and middle frontal cortex, [138] fronto-parietal and cingulo-opercular, [137] and default mode network, salience network, and thalamocortical loop areas. [133] [139]

Prevalence

2023 guidance stated fatigue prevalence is between 4.3% and 21.9%. Prevalence is higher in women than men. [6] [140]

A 2021 German study found that fatigue was the main or secondary reason for 10–20% of all consultations with a primary care physician. [141]

A large study based on the 2004 Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a biennial longitudinal survey of US adults aged 51 and above, with mean age 65, found that 33% of women and 29% of men self-reported fatigue. [142]

Diagnosis

This section needs more

reliable medical references for

verification or relies too heavily on

primary sources. (April 2024) |  |

2023 guidance [6] stated the following:

- in the primary care setting, a medical or psychiatric diagnosis is found in at least two-thirds of patients;

- the most common diagnoses are viral illness, upper respiratory infection, iron-deficiency anaemia, acute bronchitis, adverse effects of a medical agent in the proper dose, and depression or other mental disorder, such as panic disorder, and somatisation disorder;

- the origin of fatigue may be central, brain-derived, or peripheral, usually of a neuromuscular origin—it may be attributed to physical illness, psychological (e.g., psychiatric disorder), social (e.g., family problems), and physiological factors (e.g., old age), occupational illness (e.g., workplace stress);

- when unexplained, clinically evaluated chronic fatigue can be separated into ME/CFS and idiopathic chronic fatigue. [6]

A 2016 German review found that

- about 20% of people complaining of tiredness to a GP (general practitioner) suffered from a depressive disorder.

- anaemia, malignancies and other serious somatic diseases were only very rarely found in fatigued primary care patients, with prevalence rates hardly differing from non-fatigued patients.

- if fatigue occurred in primary care patients as an isolated symptom without additional abnormalities in the medical history and in the clinical examination, then extensive diagnostic testing rarely helped detect serious diseases. Such testing might also lead to false-positive tests. [143]

A 2014 Australian review recommended that a period of watchful waiting may be appropriate if there are no major warning signs. [144]

A 2009 study found that about 50% of people who had fatigue received a diagnosis that could explain the fatigue after a year with the condition. In those people who had a possible diagnosis, musculoskeletal (19.4%) and psychological problems (16.5%) were the most common. Definitive physical conditions were only found in 8.2% of cases. [145]

Treatment and Management

Management may include review of existing medications, and other factors and methods explained below.

Review of existing medications

Medications may be evaluated for side effects that contribute to fatigue [146] [78] [147][ better source needed] and the interactions of medications are complex.[ non-primary source needed] [148]

Medications to treat fatigue

The UK NICE recommends consideration of amantadine, modafinil and SSRIs for MS fatigue. [149] Psychostimulants such as methylphenidate, amphetamines, and modafinil have been used in the treatment of fatigue related to depression, [150] [151] [152] [153] and medical illness such as chronic fatigue syndrome [154] [155] and cancer. [151] [156] [157] [158] [159] [160] [161] They have also been used to counteract fatigue in sleep loss [162] and in aviation. [163]

Mental health tools

CBT has been found useful for fatigue. [164]

Improved sleep

Improving sleep can reduce fatigue. [165] [166]

Lifestyle changes

Fatigue may be reduced by reducing obesity, caffeine and alcohol intake,[ citation needed] pain and sleep disturbance, and by improving mental well-being. [167] [14] Aerobic exercise may reduce fatigue. [168] Caffeine is used by many people to manage fatigue, but may have complex effects including later tiredness. [169] [166] [170] [171]

Avoidance of body heat

Fatigue in MS has been linked to relatively high endogenous body temperature. [172] [173] [174] [175] [176] [177] [178] [179] [180] [181] [182]

Qigong and Tai Chi

Qigong and Tai chi have been postulated as helpful to reduce fatigue, but the evidence is of low quality. [183] [184] [185]

Intermittent fasting

A small 2022 study found both physical and mental fatigue were significantly reduced after three months of 16:8 intermittent fasting. [186]

Vagus nerve stimulation

A small 2023 study showed possible efficacy of vagus nerve stimulation for fatigue reduction in Sjogren's patients. [126]

Possible purposes of fatigue

Body resource management purposes

Fatigue has been posited as a bio-psycho-physiological state reflecting the body's overall strategy in resource (energy) management. Fatigue may occur when the body wants to limit resource utilisation ("rationing") in order to use resources for healing (part of sickness behaviour) [129] or conserve energy for a particular current or future anticipated need, including a threat. [14]

Evolutionary purposes

It has been posited that fatigue had evolutionary benefits in making more of the body's resources available for healing processes, such as immune responses, and in limiting disease spread by tending to reduce social interactions. [121]

Needs for research

Differentiating characteristics of fatigue due to different causes

Whilst fatigue may vary considerably by person, it may be possible to identify distinguishing characteristics linking it to different causes. [187] [33] [188]

Impact of phsychological factors

The possible influence of personal psychological factors on fatigue formation is another possible area of research. [189]

See also

- Acquiescence

- Affect

- Cancer-related fatigue

- Central governor

- Chronic stress

- Clouding of consciousness

- Combat stress reaction

- Directed attention fatigue

- Effects of fatigue on safety

- Feeling

- Gaucher's disease

- Heat illness

- Malaise

- Microsleep

- Museum fatigue

- Presenteeism

- Sleep-deprived driving

- Pacing (activity management)

- Zoom fatigue

References

- ^ "10 medical reasons for feeling tired". nhs.uk. 3 October 2018. Archived from the original on 24 November 2021. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Fatigue". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 2023-01-06. Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- ^ a b "Cancer terms". Archived from the original on 2023-01-06. Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- ^ "ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Archived from the original on 2018-08-01. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- ^ Finsterer J, Mahjoub SZ (August 2014). "Fatigue in healthy and diseased individuals". Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 31 (5): 562–575. doi: 10.1177/1049909113494748. PMID 23892338. S2CID 12582944.

- ^ a b c d e "Evaluation of fatigue - Differential diagnosis of symptoms". BMJ Best Practice. Archived from the original on 2023-12-03. Retrieved 2024-03-25.

- ^ a b c "Medically unexplained symptoms". 19 October 2017. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ^ a b Haß U, Herpich C, Norman K (September 2019). "Anti-Inflammatory Diets and Fatigue". Nutrients. 11 (10): 2315. doi: 10.3390/nu11102315. PMC 6835556. PMID 31574939.

- ^ Gandevia SC (February 1992). "Some central and peripheral factors affecting human motoneuronal output in neuromuscular fatigue". Sports Medicine. 13 (2): 93–98. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199213020-00004. PMID 1561512. S2CID 20473830.

- ^ Hagberg M (July 1981). "Muscular endurance and surface electromyogram in isometric and dynamic exercise". Journal of Applied Physiology. 51 (1): 1–7. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1981.51.1.1. PMID 7263402.

- ^ Hawley JA, Reilly T (June 1997). "Fatigue revisited". Journal of Sports Sciences. 15 (3): 245–246. doi: 10.1080/026404197367245. PMID 9232549.

- ^ a b Marcora SM, Staiano W, Manning V (March 2009). "Mental fatigue impairs physical performance in humans". Journal of Applied Physiology. 106 (3): 857–864. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.557.3566. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91324.2008. PMID 19131473. S2CID 12221961.

- ^ Martin K, Meeusen R, Thompson KG, Keegan R, Rattray B (September 2018). "Mental Fatigue Impairs Endurance Performance: A Physiological Explanation". Sports Med. 48 (9): 2041–2051. doi: 10.1007/s40279-018-0946-9. PMID 29923147. S2CID 49317682.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Davies K, Dures E, Ng WF (November 2021). "Fatigue in inflammatory rheumatic diseases: current knowledge and areas for future research". Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 17 (11): 651–664. doi: 10.1038/s41584-021-00692-1. PMID 34599320. S2CID 238233411.

- ^ a b Camera V, Mariano R, Messina S, Menke R, Griffanti L, Craner M, Leite MI, Calabrese M, Meletti S, Geraldes R, Palace JA (2 May 2023). "Shared imaging markers of fatigue across multiple sclerosis, aquaporin-4 antibody neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder and MOG antibody disease". Brain Communications. 5 (3): fcad107. doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcad107. PMC 10171455. PMID 37180990.

- ^ Hubbard AL, Golla H, Lausberg H (2020). "What's in a name? That which we call Multiple Sclerosis Fatigue". Multiple Sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England). 27 (7): 983–988. doi: 10.1177/1352458520941481. PMC 8142120. PMID 32672087.

- ^ "MeSH Browser". meshb.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2023-05-08. Retrieved 2024-01-25.

- ^ Rogers AE (April 11, 2008). "The Effects of Fatigue and Sleepiness on Nurse Performance and Patient Safety". In Hughes RG (ed.). Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Advances in Patient Safety. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). PMID 21328747 – via PubMed.

- ^ Lichstein KL, Means MK, Noe SL, Aguillard RN (August 11, 1997). "Fatigue and sleep disorders". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 35 (8): 733–740. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00029-6. PMID 9256516 – via PubMed.

- ^ Shen J, Barbera J, Shapiro CM (February 2006). "Distinguishing sleepiness and fatigue: focus on definition and measurement". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 10 (1): 63–76. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.05.004. PMID 16376590.

- ^ Goërtz YM, Braamse AM, Spruit MA, Janssen DJ, Ebadi Z, Van Herck M, Burtin C, Peters JB, Sprangers MA, Lamers F, Twisk JW, Thong MS, Vercoulen JH, Geerlings SE, Vaes AW, Beijers RJ, van Beers M, Schols AM, Rosmalen JG, Knoop H (25 October 2021). "Fatigue in patients with chronic disease: results from the population-based Lifelines Cohort Study". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 20977. Bibcode: 2021NatSR..1120977G. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-00337-z. PMC 8546086. PMID 34697347.

- ^

a

b Swain MG (2006).

"Fatigue in Liver Disease: Pathophysiology and Clinical Management". Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology. 20 (3): 181–188.

doi:

10.1155/2006/624832.

PMC

2582971.

PMID

16550262.

{{ cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI ( link) - ^ Pope JE (May 2020). "Management of Fatigue in Rheumatoid Arthritis". RMD Open. 6 (1): e001084. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2019-001084. PMC 7299512. PMID 32385141.

- ^ "Myalgische Enzephalomyelitis / Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) – Aktueller Kenntnisstand" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-11-02. Retrieved 2024-03-26.

- ^ Trust MS. "Temperature sensitivity | MS Trust". mstrust.org.uk.

- ^ "MS and heat fatigue: does it come down to sweating?".

- ^ "Fatigue in Patients With Multiple Sclerosis". Practical Neurology.

- ^ https://www.mssociety.org.uk/about-ms/types-of-ms/relapsing-remitting-ms.

- ^ a b "Presentation and Clinical Course of ME/CFS | Information for Healthcare Providers | Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome ME/CFS | CDC". www.cdc.gov. November 19, 2019.

- ^ A 2009 review found that sleep loss had a wide range of concurrent cognitive and neurobehavioral effects including unstable attention, slowing of response times, decline of memory performance, reduced learning of cognitive tasks, deterioration of performance in tasks requiring divergent thinking, perseveration with ineffective solutions, performance deterioration as task duration increases; and growing neglect of activities judged to be nonessential. Table 1. Goel N, Rao H, Durmer JS, Dinges DF (2009). "Neurocognitive Consequences of Sleep Deprivation - PMC". Seminars in Neurology. 29 (4): 320–339. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1237117. PMC 3564638. PMID 19742409.

- ^ "What is cancer fatigue?". www.cancerresearchuk.org.

- ^ "Fatigue After Brain Injury: BrainLine Talks With Dr. Nathan Zasler | BrainLine". www.brainline.org. February 4, 2010.

- ^ a b Jaime-Lara RB, Koons BC, Matura LA, Hodgson NA, Riegel B (June 2020). "A Qualitative Metasynthesis of the Experience of Fatigue Across Five Chronic Conditions". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 59 (6): 1320–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.12.358. PMC 7239763. PMID 31866485.

- ^ a b Ng WF, Bowman SJ (May 2010). "Primary Sjogren's syndrome: too dry and too tired". Rheumatology. 49 (5): 844–853. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq009. PMID 20147445.

- ^ "Fatigue | MS Trust".

- ^ Roald Omdal, Svein Ivar Mellgren, Katrine Brække Norheim (July 2021). "Pain and fatigue in primary Sjögren's syndrome". Rheumatology. 6 (7): 3099–3106. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez027. PMID 30815693.

- ^ Gerber LH, Weinstein AA, Mehta R, Younossi ZM (July 28, 2019). "Importance of fatigue and its measurement in chronic liver disease". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 25 (28): 3669–3683. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i28.3669. PMC 6676553. PMID 31391765.

- ^ a b c d e f g Zielinski MR, Systrom DM, Rose NR (2019). "Fatigue, Sleep, and Autoimmune and Related Disorders". Frontiers in Immunology. 10: 1827. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01827. PMC 6691096. PMID 31447842.

- ^ "Weakness and fatigue". Webmd. Healthwise Inc. Archived from the original on 30 December 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ^ Gandevia SC (October 2001). "Spinal and supraspinal factors in human muscle fatigue". Physiological Reviews. 81 (4): 1725–1789. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.4.1725. PMID 11581501.

- ^ Davis JM, Alderson NL, Welsh RS (August 2000). "Serotonin and central nervous system fatigue: nutritional considerations". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 72 (2 Suppl): 573S–578S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.2.573S. PMID 10919962.

- ^ Perrier JF, Delgado-Lezama R (August 2005). "Synaptic release of serotonin induced by stimulation of the raphe nucleus promotes plateau potentials in spinal motoneurons of the adult turtle". The Journal of Neuroscience. 25 (35): 7993–7999. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1957-05.2005. PMC 6725458. PMID 16135756.

- ^ Cotel F, Exley R, Cragg SJ, Perrier JF (March 2013). "Serotonin spillover onto the axon initial segment of motoneurons induces central fatigue by inhibiting action potential initiation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (12): 4774–4779. Bibcode: 2013PNAS..110.4774C. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216150110. PMC 3607056. PMID 23487756.

- ^ Enoka RM, Duchateau J (January 2008). "Muscle fatigue: what, why and how it influences muscle function". The Journal of Physiology. 586 (1): 11–23. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.139477. PMC 2375565. PMID 17702815.

- ^ Lin H, Saunders B, Friese M, Evans NJ, Inzlicht M (May 2020). "Strong Effort Manipulations Reduce Response Caution: A Preregistered Reinvention of the Ego-Depletion Paradigm". Psychological Science. 31 (5): 531–547. doi: 10.1177/0956797620904990. PMC 7238509. PMID 32315259.

- ^ Giannini AJ (1991). "Fatigue, Chronic". In Taylor RB (ed.). Difficult Diagnosis 2. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-7216-3481-4. OCLC 954530793.

- ^ Possin KL, Moskowitz T, Erlhoff SJ, Rogers KM, Johnson ET, Steele NZ, Higgins JJ, Stiver J, Alioto AG, Farias ST, Miller BL, Rankin KP (January 2018). "The Brain Health Assessment for Detecting and Diagnosing Neurocognitive Disorders". J Am Geriatr Soc. 66 (1): 150–156. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15208. PMC 5889617. PMID 29355911.

- ^ Menzies V, Kelly DL, Yang GS, Starkweather A, Lyon DE (June 2021). "A systematic review of the association between fatigue and cognition in chronic noncommunicable diseases". Chronic Illn. 17 (2): 129–150. doi: 10.1177/1742395319836472. PMC 6832772. PMID 30884965.

- ^ Elliott TR, Hsiao YY, Randolph K, Urban RJ, Sheffield-Moore M, Pyles RB, Masel BE, Wexler T, Wright TJ (2023). "Efficient assessment of brain fog and fatigue: Development of the Fatigue and Altered Cognition Scale (FACs)". PLOS ONE. 18 (12): e0295593. Bibcode: 2023PLoSO..1895593E. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0295593. PMC 10712873. PMID 38079429.

- ^ Ishii A, Tanaka M, Watanabe Y (2014). "Neural mechanisms of mental fatigue". Rev Neurosci. 25 (4): 469–79. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2014-0028. PMID 24926625.

- ^ Garcia-Rill E, Virmani T, Hyde JR, D'Onofrio S, Mahaffey S (2016). "Arousal and the control of perception and movement". Curr Trends Neurol. 10: 53–64. PMC 5501251. PMID 28690375.

- ^ Jones BE (January 2020). "Arousal and sleep circuits". Neuropsychopharmacology. 45 (1): 6–20. doi: 10.1038/s41386-019-0444-2. PMC 6879642. PMID 31216564.

- ^ Taran S, Gros P, Gofton T, Boyd G, Briard JN, Chassé M, Singh JM (April 2023). "The reticular activating system: a narrative review of discovery, evolving understanding, and relevance to current formulations of brain death". Can J Anaesth. 70 (4): 788–795. doi: 10.1007/s12630-023-02421-6. PMC 10203024. PMID 37155119.

- ^ Arguinchona JH, Tadi P (2024). Neuroanatomy, Reticular Activating System. PMID 31751025.

- ^ "Drowsy Driving is Impaired Driving". National Safety Council. Archived from the original on 1 February 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ Hubbard AL, Golla H, Lausberg H (June 2021). "What's in a name? That which we call Multiple Sclerosis Fatigue". Multiple Sclerosis. 27 (7): 983–988. doi: 10.1177/1352458520941481. PMC 8142120. PMID 32672087.

- ^ Mills RJ, Young CA, Pallant JF, Tennant A (February 2010). "Development of a patient reported outcome scale for fatigue in multiple sclerosis: The Neurological Fatigue Index (NFI-MS)". Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 8: 22. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-22. PMC 2834659. PMID 20152031.

- ^ "TikTok - Make Your Day". www.tiktok.com. Archived from the original on 2024-03-26. Retrieved 2024-03-26.

- ^ Piraino B, Vollmer-Conna U, Lloyd A (May 2012). "Genetic associations of fatigue and other symptom domains of the acute sickness response to infection". Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 26 (4): 552–558. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.12.009. PMC 7127134. PMID 22227623.

- ^ Billones R, Liwang JK, Butler K, Graves L, Saligan LN (August 2021). "Dissecting the fatigue experience: A scoping review of fatigue definitions, dimensions, and measures in non-oncologic medical conditions". Brain Behav Immun Health. 15: 100266. doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2021.100266. PMC 8474156. PMID 34589772.

- ^ Griffith JP, Zarrouf FA (2008). "A systematic review of chronic fatigue syndrome: don't assume it's depression". Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 10 (2): 120–8. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v10n0206. PMC 2292451. PMID 18458765.

- ^ Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, Sharpe MC, Dobbins JG, Komaroff A (December 1994). "The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group". Annals of Internal Medicine. 121 (12): 953–959. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-12-199412150-00009. PMID 7978722. S2CID 510735.

- ^ Hemmett L, Holmes J, Barnes M, Russell N (October 2004). "What drives quality of life in multiple sclerosis?". QJM. 97 (10): 671–676. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hch105. PMID 15367738.

- ^ Mæland E, Miyamoto ST, Hammenfors D, Valim V, Jonsson MV (2021). "Understanding Fatigue in Sjögren's Syndrome: Outcome Measures, Biomarkers and Possible Interventions". Frontiers in Immunology. 12: 703079. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.703079. PMC 8267792. PMID 34249008.

- ^ Fredriksson-Larsson U, Alsen P, Brink E (January 21, 2013). "I've lost the person I used to be— Experiences of the consequences of fatigue following myocardial infarction". International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being. 8 (1): 20836. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v8i0.20836. PMC 3683631. PMID 23769653.

- ^ "ICD-11 - Mortality and Morbidity Statistics | MG22 Fatigue". World Health Organization. 2019. Archived from the original on 2018-08-01. Retrieved 2023-04-25.

-

^

- 8E49 Postviral fatigue syndrome

- QE84 Acute stress reaction, Combat fatigue

- 6A70-6A7Z Depressive disorders

- 07 Sleep-wake disorders

- FB32.5 Muscle strain or sprain, causing muscular fatigue

- NF01.3 Heat fatigue, transient

- MA82.Y Voice disturbances, causing voice fatigue

- BD1Z Heart failure, unspecified, causing myocardial fatigue

- JA65.Y Conditions predominantly related to pregnancy, causing fatigue which complicates pregnancy

- SD91 Fatigue consumption disorder, causing coughing, fever, diarrhea, chest pain etc.

- MG2A Ageing associated decline in intrinsic capacity, causing senile fatigue

- NF07.2 Exhaustion due to exposure

- NF01 Heat exhaustion

- 6C20 Bodily distress disorder.

- ^ Desai G, Sagar R, Chaturvedi SK (2018). "Nosological journey of somatoform disorders: From briquet's syndrome to bodily distress disorder". Indian Journal of Social Psychiatry. 34 (5): 29. doi: 10.4103/ijsp.ijsp_37_18.

- ^ Basavarajappa C, Dahale AB, Desai G (September 2020). "Evolution of bodily distress disorders". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 33 (5): 447–450. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000630. PMID 32701520. S2CID 220731306.

- ^ "Depression Definition and DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria". www.psycom.net. August 26, 2022. Archived from the original on February 13, 2024. Retrieved March 21, 2024.

- ^ Machado MO, Kang NY, Tai F, Sambhi RD, Berk M, Carvalho AF, Chada LP, Merola JF, Piguet V, Alavi A (September 2021). "Measuring fatigue: a meta-review". International Journal of Dermatology. 60 (9): 1053–1069. doi: 10.1111/ijd.15341. hdl: 11343/276722. PMID 33301180. S2CID 228087205.

-

^

"Archived copy" (PDF).

Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-01-30. Retrieved 2024-03-26.

{{ cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title ( link) - ^ Valko PO, Bassetti CL, Bloch KE, Held U, Baumann CR (2008). "Validation of the Fatigue Severity Scale in a Swiss Cohort - PMC". Sleep. 31 (11): 1601–1607. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.11.1601. PMC 2579971. PMID 19014080.

-

^

"Archived copy" (PDF).

Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-03-29. Retrieved 2024-03-26.

{{ cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title ( link) - ^ "Fatigue Survey Results Released". 23 March 2015. Archived from the original on 6 January 2023. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ^ "Nintendo's first health care device will be sleep and fatigue tracker". The Japan Times. Reuters. 30 October 2014. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ^ "Nintendo presses snooze button on planned sleep-tracking device". 4 February 2016. Archived from the original on 6 January 2023. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ^ a b c "Fatigue Causes". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 2023-01-06. Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- ^ "Consequences of Fatigue from Insufficient Sleep". Commercial Motor Vehicle Driver Fatigue, Long-Term Health, and Highway Safety: Research Needs. National Academies Press (US). 12 August 2016. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ Kayser KC, Puig VA, Estepp JR (February 25, 2022). "Predicting and mitigating fatigue effects due to sleep deprivation: A review". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 16. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.930280. PMC 9389006. PMID 35992930.

- ^ Strober LB (12 February 2015). "Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis: A Look at the Role of Poor Sleep". Frontiers in Neurology. 6: 21. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2015.00021. PMC 4325921. PMID 25729378.

- ^ GudbjöRnsson B, Broman JE, Hetta J, HäLlgren R (1993). "SLEEP DISTURBANCES IN PATIENTS WITH PRIMARY SJÖGREN'S SYNDROME". Rheumatology. 32 (12): 1072–1076. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/32.12.1072. PMID 8252317.

- ^ Strober LB (2015). "Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: a look at the role of poor sleep". Frontiers in Neurology. 6: 21. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2015.00021. PMC 4325921. PMID 25729378.

- ^ https://academic.oup.com/rheumatology/article/49/7/1294/1786149

- ^ Dey M, Parodis I, Nikiphorou E (January 26, 2021). "Fatigue in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Comparison of Mechanisms, Measures and Management". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 10 (16): 3566. doi: 10.3390/jcm10163566. PMC 8396818. PMID 34441861.

- ^ Hafiz W, Nori R, Bregasi A, Noamani B, Bonilla D, Lisnevskaia L, Silverman E, Bookman AA, Johnson SR, Landolt-Marticorena C, Wither J (2019). "Fatigue severity in anti-nuclear antibody-positive individuals does not correlate with pro-inflammatory cytokine levels or predict imminent progression to symptomatic disease". Arthritis Research & Therapy. 21 (1): 223. doi: 10.1186/s13075-019-2013-9. PMC 6827224. PMID 31685018.

- ^ A 2015 US survey found that 98% of people with autoimmune diseases experienced fatigue, 89% said it was a "major issue", 68% said "fatigue is anything but normal. It is profound and prevents [them] from doing the simplest everyday tasks." and 59% said it was "probably the most debilitating symptom of having an AD." https://autoimmune.org/fatigue-survey-results-released/ Archived 2023-01-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Fatigue after brain injury". Archived from the original on 2023-01-06. Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- ^ "The daily struggle of living with extreme fatigue". www.bbc.com.

- ^ "What is cancer fatigue? | Coping physically | Cancer Research UK". Archived from the original on 2023-01-06. Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- ^ "Long-term effects of coronavirus (Long COVID)". 7 January 2021. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ^ Williams ZJ, Gotham KO (2021-10-03), Current and Lifetime Somatic Symptom Burden Among Transition-aged Autistic Young Adults (PDF), Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, doi: 10.1101/2021.10.02.21264461, S2CID 238252764

- ^ a b c d e Friedman HH (2001). Problem-oriented Medical Diagnosis. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-7817-2909-3.

- ^ Alsén P, Brink E, Brändström Y, Karlson BW, Persson LO (August 27, 2010). "Fatigue after myocardial infarction: relationships with indices of emotional distress, and sociodemographic and clinical variables". International Journal of Nursing Practice. 16 (4): 326–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2010.01848.x. PMID 20649663. Archived from the original on March 27, 2024. Retrieved March 27, 2024 – via PubMed.

- ^ Whitehead WE, Palsson O, Jones KR (April 2002). "Systematic review of the comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: what are the causes and implications?". Gastroenterology. 122 (4): 1140–1156. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32392. PMID 11910364.

- ^ Gibson PR, Newnham E, Barrett JS, Shepherd SJ, Muir JG (February 2007). "Review article: fructose malabsorption and the bigger picture". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 25 (4): 349–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03186.x. PMID 17217453. S2CID 11487905.

- ^ a b Avellaneda Fernández A, Pérez Martín A, Izquierdo Martínez M, Arruti Bustillo M, Barbado Hernández FJ, de la Cruz Labrado J, et al. (October 2009). "Chronic fatigue syndrome: aetiology, diagnosis and treatment". BMC Psychiatry. 9 (Suppl 1): S1. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-S1-S1. PMC 2766938. PMID 19857242.

- ^ Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5th edition: DSM-5. Arlington, VA Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association. 2013. p. 189–195. ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8. OCLC 830807378.

- ^ "ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Archived from the original on 2024-02-23. Retrieved 2024-03-26.

- ^ Son CG (2019-06-01). "Differential diagnosis between "chronic fatigue" and "chronic fatigue syndrome"". Integrative Medicine Research. 8 (2): 89–91. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2019.04.005. ISSN 2213-4220. PMC 6522773. PMID 31193269.

- ^ van Campen C(, Visser FC (June 19, 2021). "Comparing Idiopathic Chronic Fatigue and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) in Males: Response to Two-Day Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing Protocol". Healthcare. 9 (6): 683. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9060683. PMC 8230194. PMID 34198946.

-

^

"ICD-11 - Mortality and Morbidity Statistics | MG22 Fatigue". World Health Organization. 2019.

Archived from the original on 2018-08-01. Retrieved 2023-04-25.

This includes a category MG22 Fatigue (typically fatigue following exertion but sometimes may occur in the absence of such exertion as a symptom of health conditions), and many other categories where fatigue is mentioned as a secondary result of other factors.

- 8E49 Postviral fatigue syndrome

- QE84 Acute stress reaction, Combat fatigue

- 6A70-6A7Z Depressive disorders

- 07 Sleep-wake disorders

- FB32.5 Muscle strain or sprain, causing muscular fatigue

- NF01.3 Heat fatigue, transient

- MA82.Y Voice disturbances, causing voice fatigue

- BD1Z Heart failure, unspecified, causing myocardial fatigue

- JA65.Y Conditions predominantly related to pregnancy, causing fatigue which complicates pregnancy

- SD91 Fatigue consumption disorder, causing coughing, fever, diarrhea, chest pain etc.

- MG2A Ageing associated decline in intrinsic capacity, causing senile fatigue

- NF07.2 Exhaustion due to exposure

- NF01 Heat exhaustion

- 6C20 Bodily distress disorder.

- ^ "Fatigue in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis". Archived from the original on 2022-06-16. Retrieved 2021-10-18.

- ^ Chalah MA, Riachi N, Ahdab R, Créange A, Lefaucheur JP, Ayache SS (2015). "Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis: Neural Correlates and the Role of Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation". Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 9: 460. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00460. PMC 4663273. PMID 26648845.

- ^ Gerber LH, Weinstein AA, Mehta R, Younossi ZM (July 2019). "Importance of fatigue and its measurement in chronic liver disease". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 25 (28): 3669–3683. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i28.3669. PMC 6676553. PMID 31391765.

- ^ Hartvig Honoré P (June 2013). "Fatigue". European Journal of Hospital Pharmacy. 20 (3): 147–148. doi: 10.1136/ejhpharm-2013-000309. S2CID 220171226.

- ^ Newland P, Starkweather A, Sorenson M (2016). "Central fatigue in multiple sclerosis: a review of the literature: The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine: Vol 39, No 4". The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine. 39 (4): 386–399. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2016.1168587. PMC 5102292. PMID 27146427.

- ^ Patejdl R, Zettl UK (27 July 2022). "The pathophysiology of motor fatigue and fatigability in multiple sclerosis". Frontiers in Neurology. 13. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.891415. PMC 9363784. PMID 35968278.

- ^ "ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Archived from the original on 2018-08-01. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- ^ Resnick HE, Carter EA, Aloia M, Phillips B (15 April 2006). "Cross-Sectional Relationship of Reported Fatigue to Obesity, Diet, and Physical Activity: Results From the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 02 (2): 163–169. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.26511.

- ^ Lim W, Hong S, Nelesen R, Dimsdale JE (25 April 2005). "The Association of Obesity, Cytokine Levels, and Depressive Symptoms With Diverse Measures of Fatigue in Healthy Subjects". Archives of Internal Medicine. 165 (8): 910–915. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.8.910. PMID 15851643.

- ^ "Obesity". nhs.uk. November 23, 2017. Archived from the original on March 21, 2024. Retrieved March 21, 2024.

- ^ "Tiredness and fatigue". 26 April 2018. Archived from the original on 6 January 2023. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ^ "Evaluation of fatigue - Differential diagnosis of symptoms | BMJ Best Practice US". Archived from the original on 2023-06-04. Retrieved 2024-01-30.

- ^ D'Souza RS, Hooten WM (2024). "Somatic Symptom Disorder". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30335286.

- ^ "Evaluation of fatigue - Differential diagnosis of symptoms | BMJ Best Practice US". bestpractice.bmj.com. Archived from the original on 2023-06-04. Retrieved 2024-03-25.

- ^ "Somatic symptom disorder - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 2024-03-26. Retrieved 2024-03-25.

- ^ Cadegiani FA, Kater CE (24 August 2016). "Adrenal fatigue does not exist: a systematic review". BMC Endocrine Disorders. 16 (1): 48. doi: 10.1186/s12902-016-0128-4. ISSN 1472-6823. PMC 4997656. PMID 27557747.

- ^ Whitbourne K (February 7, 2021). "Adrenal Fatigue: Is It Real?". WebMD. Metcalf, Eric. Retrieved 2014-03-19.

-

^ Shah R, Greenberger PA (2012-05-01).

"Chapter 29: Unproved and controversial methods and theories in allergy-immunology". Allergy and Asthma Proceedings. 33 (3): 100–102.

doi:

10.2500/aap.2012.33.3562.

ISSN

1088-5412.

PMID

22794702.

There is no scientific basis for the existence of this disorder and no conclusive method for diagnosis

- ^ a b Korte SM, Straub RH (November 15, 2019). "Fatigue in inflammatory rheumatic disorders: pathophysiological mechanisms". Rheumatology. 58 (Suppl 5): v35–v50. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez413. PMC 6827268. PMID 31682277.

- ^ Korte SM, Straub RH (November 2019). "Fatigue in inflammatory rheumatic disorders: pathophysiological mechanisms". Rheumatology. 58 (Suppl 5): v35–v50. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez413. PMC 6827268. PMID 31682277.

- ^ Omdal R (June 2020). "The biological basis of chronic fatigue: neuroinflammation and innate immunity". Current Opinion in Neurology. 33 (3): 391–396. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000817. PMID 32304437. S2CID 215819309.

- ^ Lacourt TE, Vichaya EG, Chiu GS, Dantzer R, Heijnen CJ (2018). "The High Costs of Low-Grade Inflammation: Persistent Fatigue as a Consequence of Reduced Cellular-Energy Availability and Non-adaptive Energy Expenditure". Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 12: 78. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00078. PMC 5932180. PMID 29755330.

- ^ Karshikoff B, Sundelin T, Lasselin J (2017). "Role of Inflammation in Human Fatigue: Relevance of Multidimensional Assessments and Potential Neuronal Mechanisms". Frontiers in Immunology. 8: 21. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00021. PMC 5247454. PMID 28163706.

- ^ a b Tarn J, Evans E, Traianos E, Collins A, Stylianou M, Parikh J, Bai Y, Guan Y, Frith J, Lendrem D, Macrae V, McKinnon I, Simon BS, Blake J, Baker MR, Taylor JP, Watson S, Gallagher P, Blamire A, Newton J, Ng WF (April 2023). "The Effects of Noninvasive Vagus Nerve Stimulation on Fatigue in Participants With Primary Sjögren's Syndrome" (PDF). Neuromodulation: Technology at the Neural Interface. 26 (3): 681–689. doi: 10.1016/j.neurom.2022.08.461. PMID 37032583.

- ^ Corbitt M, Eaton-Fitch N, Staines D, Cabanas H, Marshall-Gradisnik S (August 24, 2019). "A systematic review of cytokines in chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis/systemic exertion intolerance disease (CFS/ME/SEID)". BMC Neurology. 19 (1): 207. doi: 10.1186/s12883-019-1433-0. PMC 6708220. PMID 31445522.

- ^ Bårdsen K, Nilsen MM, Kvaløy JT, Norheim KB, Jonsson G, Omdal R (2016). "Heat shock proteins and chronic fatigue in primary Sjögren's syndrome". Innate Immunity. 22 (3): 162–167. doi: 10.1177/1753425916633236. PMC 4804286. PMID 26921255.

- ^ a b Grimstad T, Kvivik I, Kvaløy JT, Aabakken L, Omdal R (February 2020). "Heat-shock protein 90 α in plasma reflects severity of fatigue in patients with Crohn's disease". Innate Immunity. 26 (2): 146–151. doi: 10.1177/1753425919879988. PMC 7016405. PMID 31601148.

- ^ Norheim KB, Harboe E, Gøransson LG, Omdal R (10 January 2012). "Interleukin-1 Inhibition and Fatigue in Primary Sjögren's Syndrome – A Double Blind, Randomised Clinical Trial". PLOS ONE. 7 (1): e30123. Bibcode: 2012PLoSO...730123N. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030123. PMC 3254637. PMID 22253903.

- ^ Omdal R, Gunnarsson R (September 2005). "The effect of interleukin-1 blockade on fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis—a pilot study". Rheumatology International. 25 (6): 481–484. doi: 10.1007/s00296-004-0463-z. PMID 15071755.

- ^ Skoie IM, Bårdsen K, Nilsen MM, Eidem LE, Grimstad T, Dalen I, Omdal R (June 2022). "Fatigue and expression of heat-shock protein genes in plaque psoriasis". Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 47 (6): 1068–1077. doi: 10.1111/ced.15068. PMID 34921435.

- ^ a b Qi P, Ru H, Gao L, Zhang X, Zhou T, Tian Y, Thakor N, Bezerianos A, Li J, Sun Y (April 1, 2019). "Neural Mechanisms of Mental Fatigue Revisited: New Insights from the Brain Connectome". Engineering. 5 (2): 276–286. Bibcode: 2019Engin...5..276Q. doi: 10.1016/j.eng.2018.11.025.

- ^ Schaechter JD, Kim M, Hightower BG, Ragas T, Loggia ML (February 28, 2023). "Disruptions in Structural and Functional Connectivity Relate to Poststroke Fatigue". Brain Connectivity. 13 (1): 15–27. doi: 10.1089/brain.2022.0021. PMC 9942175. PMID 35570655.

- ^ Cruz Gómez ÁJ, Ventura Campos N, Belenguer A, Ávila C, Forn C (October 22, 2013). "Regional Brain Atrophy and Functional Connectivity Changes Related to Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis". PLOS ONE. 8 (10): e77914. Bibcode: 2013PLoSO...877914C. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077914. PMC 3805520. PMID 24167590.

- ^ Gay CW, Robinson ME, Lai S, O'Shea A, Craggs JG, Price DD, Staud R (February 1, 2016). "Abnormal Resting-State Functional Connectivity in Patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Results of Seed and Data-Driven Analyses". Brain Connectivity. 6 (1): 48–56. doi: 10.1089/brain.2015.0366. PMC 4744887. PMID 26449441.

- ^ a b Ramage AE, Ray KL, Franz HM, Tate DF, Lewis JD, Robin DA (January 30, 2021). "Cingulo-Opercular and Frontoparietal Network Control of Effort and Fatigue in Mild Traumatic Brain Injury". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 15. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2021.788091. PMC 8866657. PMID 35221951.

- ^ a b Nordin LE, Möller MC, Julin P, Bartfai A, Hashim F, Li TQ (February 16, 2016). "Post mTBI fatigue is associated with abnormal brain functional connectivity". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 21183. Bibcode: 2016NatSR...621183N. doi: 10.1038/srep21183. PMC 4754765. PMID 26878885.

- ^ Borghetti L, Rhodes LJ, Morris MB (September 2022). "Fatigue Leads to Dynamic Shift in Fronto-parietal Sustained Attention Network". Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting. 66 (1): 606–610. doi: 10.1177/1071181322661056. S2CID 253205546.

- ^ Loge JH, Ekeberg Ø, Kaasa S (July 1998). "Fatigue in the general norwegian population". Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 45 (1): 53–65. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(97)00291-2. PMID 9720855.

- ^ Maisel P, Baum E, Donner-Banzhoff N (August 30, 2021). "Fatigue as the Chief Complaint". Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 118 (33–34): 566–576. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.m2021.0192. PMC 8579431. PMID 34196270.

- ^ Meng H, Hale L, Friedberg F (2010). "Prevalence and Predictors of Fatigue Among Middle-Aged and Older Adults: Evidence from the Health and Retirement Study - PMC". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 58 (10): 2033–2034. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03088.x. PMC 2981161. PMID 20929479.

- ^ Stadje R, Dornieden K, Baum E, Becker A, Biroga T, Bösner S, Haasenritter J, Keunecke C, Viniol A, Donner-Banzhoff N (October 20, 2016). "The differential diagnosis of tiredness: a systematic review". BMC Family Practice. 17 (1): 147. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0545-5. PMC 5072300. PMID 27765009.

- ^ Practitioners TR. "Fatigue – a rational approach to investigation". Australian Family Physician. Archived from the original on 2024-03-27. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ Nijrolder I, van der Windt D, de Vries H, van der Horst H (November 2009). "Diagnoses during follow-up of patients presenting with fatigue in primary care". CMAJ. 181 (10): 683–687. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090647. PMC 2774363. PMID 19858240.

- ^ Siniscalchi A, Gallelli L, Russo E, De Sarro G (October 2013). "A review on antiepileptic drugs-dependent fatigue: pathophysiological mechanisms and incidence". European Journal of Pharmacology. 718 (1–3): 10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.09.013. PMID 24051268.

- ^ "What to do when medication makes you sleepy". 8 March 2016. Archived from the original on 9 November 2021. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ Phansalkar S, van der Sijs H, Tucker AD, Desai AA, Bell DS, Teich JM, et al. (May 2013). "Drug-drug interactions that should be non-interruptive in order to reduce alert fatigue in electronic health records". Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 20 (3): 489–493. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001089. PMC 3628052. PMID 23011124.

- ^ "Recommendations | Multiple sclerosis in adults: management | Guidance | NICE". www.nice.org.uk. June 22, 2022. Archived from the original on January 7, 2023. Retrieved January 7, 2023.

- ^ Candy M, Jones L, Williams R, Tookman A, King M (April 2008). "Psychostimulants for depression". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD006722. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006722.pub2. PMID 18425966.

- ^ a b Hardy SE (February 2009). "Methylphenidate for the treatment of depressive symptoms, including fatigue and apathy, in medically ill older adults and terminally ill adults". Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 7 (1): 34–59. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2009.02.006. PMC 2738590. PMID 19281939.

- ^ Malhi GS, Byrow Y, Bassett D, Boyce P, Hopwood M, Lyndon W, Mulder R, Porter R, Singh A, Murray G (March 2016). "Stimulants for depression: On the up and up?". Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 50 (3): 203–207. doi: 10.1177/0004867416634208. PMID 26906078. S2CID 45341424.

- ^ Bahji A, Mesbah-Oskui L (September 2021). "Comparative efficacy and safety of stimulant-type medications for depression: A systematic review and network meta-analysis". J Affect Disord. 292: 416–423. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.119. PMID 34144366.

- ^ Van Houdenhove B, Pae CU, Luyten P (February 2010). "Chronic fatigue syndrome: is there a role for non-antidepressant pharmacotherapy?". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 11 (2): 215–223. doi: 10.1517/14656560903487744. PMID 20088743. S2CID 34827174.

- ^ Valdizán Usón JR, Idiazábal Alecha MA (June 2008). "Diagnostic and treatment challenges of chronic fatigue syndrome: role of immediate-release methylphenidate". Expert Rev Neurother. 8 (6): 917–927. doi: 10.1586/14737175.8.6.917. PMID 18505357. S2CID 37482754.

- ^ Masand PS, Tesar GE (September 1996). "Use of stimulants in the medically ill". Psychiatr Clin North Am. 19 (3): 515–547. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70304-x. PMID 8856815.

- ^ Breitbart W, Alici Y (August 2010). "Psychostimulants for cancer-related fatigue". J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 8 (8): 933–942. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0068. PMID 20870637.

- ^ Minton O, Richardson A, Sharpe M, Hotopf M, Stone PC (April 2011). "Psychostimulants for the management of cancer-related fatigue: a systematic review and meta-analysis". J Pain Symptom Manage. 41 (4): 761–767. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.06.020. PMID 21251796.

- ^ Gong S, Sheng P, Jin H, He H, Qi E, Chen W, Dong Y, Hou L (2014). "Effect of methylphenidate in patients with cancer-related fatigue: a systematic review and meta-analysis". PLOS ONE. 9 (1): e84391. Bibcode: 2014PLoSO...984391G. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084391. PMC 3885551. PMID 24416225.

- ^ Yennurajalingam S, Bruera E (2014). "Review of clinical trials of pharmacologic interventions for cancer-related fatigue: focus on psychostimulants and steroids". Cancer J. 20 (5): 319–324. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000069. PMID 25299141. S2CID 29351114.

- ^ Dobryakova E, Genova HM, DeLuca J, Wylie GR (2015). "The dopamine imbalance hypothesis of fatigue in multiple sclerosis and other neurological disorders". Front Neurol. 6: 52. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2015.00052. PMC 4357260. PMID 25814977.

- ^ Bonnet MH, Balkin TJ, Dinges DF, Roehrs T, Rogers NL, Wesensten NJ (September 2005). "The use of stimulants to modify performance during sleep loss: a review by the sleep deprivation and Stimulant Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine". Sleep. 28 (9): 1163–1187. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.9.1163. PMID 16268386.

- ^ Ehlert AM, Wilson PB (March 2021). "Stimulant Use as a Fatigue Countermeasure in Aviation". Aerosp Med Hum Perform. 92 (3): 190–200. doi: 10.3357/AMHP.5716.2021. PMID 33754977. S2CID 232325161.

- ^ "Self-help tips to fight tiredness". nhs.uk. January 27, 2022. Archived from the original on January 31, 2024. Retrieved January 31, 2024.

- ^ Orlandi AC, Ventura C, Gallinaro AL, Costa RA, Lage LV (October 11, 2012). "Improvement in pain, fatigue, and subjective sleep quality through sleep hygiene tips in patients with fibromyalgia". Revista Brasileira de Reumatologia. 52 (5): 666–678. PMID 23090368 – via PubMed.

- ^ a b "Self-help tips to fight tiredness". nhs.uk. January 27, 2022.

- ^ Geenen R, Dures E (November 2019). "A biopsychosocial network model of fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review". Rheumatology. 58 (Supplement_5): v10–v21. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez403. PMC 6827269. PMID 31682275.

- ^ Strombeck BE, Theander E, Jacobsson LT (31 March 2007). "Effects of exercise on aerobic capacity and fatigue in women with primary Sjogren's syndrome". Rheumatology. 46 (5): 868–871. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem004. PMID 17308315.

- ^ "Exercise versus caffeine: Which is your best ally to fight fatigue?". Harvard Health. June 8, 2017.

- ^ Yan W (7 September 2021). "Why Does Coffee Sometimes Make Me Tired?". The New York Times.

- ^ McLellan TM, Caldwell JA, Lieberman HR (December 1, 2016). "A review of caffeine's effects on cognitive, physical and occupational performance". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 71: 294–312. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.09.001. PMID 27612937.

- ^ "Heat Sensitivity". Archived from the original on 2024-01-17. Retrieved 2024-03-15.

- ^ Trust MS. "Temperature sensitivity | MS Trust". mstrust.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2024-01-17. Retrieved 2024-03-15.

- ^ Staff B (August 11, 2014). "Higher Body Temperature in RRMS Patients Could Cause Increased Fatigue". multiplesclerosisnewstoday.com. Archived from the original on March 15, 2024. Retrieved March 15, 2024.

- ^ Sumowski JF, Leavitt VM (July 15, 2014). "Body temperature is elevated and linked to fatigue in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, even without heat exposure". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 95 (7): 1298–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.02.004. PMC 4071126. PMID 24561056.

- ^ Leavitt VM, De Meo E, Riccitelli G, Rocca MA, Comi G, Filippi M, Sumowski JF (November 2015). "Elevated body temperature is linked to fatigue in an Italian sample of relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis patients". Journal of Neurology. 262 (11): 2440–2442. doi: 10.1007/s00415-015-7863-8. PMID 26223805.

- ^ Manjaly ZM, Harrison NA, Critchley HD, Do CT, Stefanics G, Wenderoth N, et al. (June 2019). "Pathophysiological and cognitive mechanisms of fatigue in multiple sclerosis". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 90 (6): 642–651. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-320050. PMC 6581095. PMID 30683707.

- ^ Ellison PM, Goodall S, Kennedy N, Dawes H, Clark A, Pomeroy V, et al. (September 2022). "Neurostructural and Neurophysiological Correlates of Multiple Sclerosis Physical Fatigue: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cross-Sectional Studies". Neuropsychology Review. 32 (3): 506–519. doi: 10.1007/s11065-021-09508-1. PMC 9381450. PMID 33961198.

- ^ Newland P, Starkweather A, Sorenson M (2016). "Central fatigue in multiple sclerosis: A review of the literature". The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine. 39 (4): 386–399. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2016.1168587. PMC 5102292. PMID 27146427.

- ^ Christogianni A, O'Garro J, Bibb R, Filtness A, Filingeri D (November 2022). "Heat and cold sensitivity in multiple sclerosis: A patient-centred perspective on triggers, symptoms, and thermal resilience practices" (PDF). Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. 67: 104075. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2022.104075. PMID 35963205.

- ^ Davis SL, Wilson TE, White AT, Frohman EM (November 15, 2010). "Thermoregulation in multiple sclerosis". Journal of Applied Physiology. 109 (5): 1531–1537. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00460.2010. PMC 2980380. PMID 20671034.

- ^ Davis SL, Jay O, Wilson TE (2018). "Thermoregulatory dysfunction in multiple sclerosis". Thermoregulation: From Basic Neuroscience to Clinical Neurology, Part II. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 157. pp. 701–714. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-64074-1.00042-2. ISBN 978-0-444-64074-1. PMID 30459034.

- ^ Xiang Y, Lu L, Chen X, Wen Z (5 April 2017). "Does Tai Chi relieve fatigue? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". PLOS ONE. 12 (4): e0174872. Bibcode: 2017PLoSO..1274872X. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174872. PMC 5381792. PMID 28380067.

- ^ Wang R, Huang X, Wu Y, Sun D (22 June 2021). "Efficacy of Qigong Exercise for Treatment of Fatigue: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Frontiers in Medicine. 8. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.684058. PMC 8257957. PMID 34239889.

- ^ Chan JS, Ng S, Yuen L, Chan CL (2019). "Qigong exercise for chronic fatigue syndrome". Exercise on Brain Health. International Review of Neurobiology. Vol. 147. pp. 121–153. doi: 10.1016/bs.irn.2019.08.002. ISBN 978-0-12-816967-4. PMID 31607352.

- ^ Anic K, Schmidt MW, Furtado L, Weidenbach L, Battista MJ, Schmidt M, Schwab R, Brenner W, Ruckes C, Lotz J, Lackner KJ, Hasenburg A, Hasenburg A (October 10, 2022). "Intermittent Fasting—Short- and Long-Term Quality of Life, Fatigue, and Safety in Healthy Volunteers: A Prospective, Clinical Trial". Nutrients. 14 (19): 4216. doi: 10.3390/nu14194216. PMC 9571750. PMID 36235868.

- ^ Billones R, Liwang JK, Butler K, Graves L, Saligan LN (2021). "Dissecting the fatigue experience: A scoping review of fatigue definitions, dimensions, and measures in non-oncologic medical conditions - PMC". Brain, Behavior, & Immunity - Health. 15. doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2021.100266. PMC 8474156. PMID 34589772.

- ^ see section on Characteristics by cause above.

- ^ Schreiber H, Lang M, Kiltz K, Lang C (4 February 2015). "Is Personality Profile a Relevant Determinant of Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis?". Frontiers in Neurology. 6: 2. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2015.00002. PMC 4316719. PMID 25699007.

Further reading

-

Byung-Chul Han: Müdigkeitsgesellschaft. Matthes & Seitz, Berlin 2010,

ISBN

978-3-88221-616-5. (Philosophical essay about fatigue as a sociological problem and symptom).

- Danish edition: Træthedssamfundet. Møller, 2012, ISBN 978-87-994043-7-7.

- Dutch edition: De vermoeide samenleving. van gennep, 2012, ISBN 978-94-6164-071-0.

- Italian editions: La società della stanchezza. nottetempo, 2012, ISBN 978-88-7452-345-0.

- Korean edition: 한병철 지음 | 김태환 옮김. Moonji, 2011, ISBN 978-89-320-2396-0.

- Spanish edition: La sociedad del cansancio. Herder Editorial, 2012, ISBN 978-84-254-2868-5.

External links

- Fatigue – Information for Patients, U.S. National Cancer Institute