| War of the second fall of Ayutthaya | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Burmese–Siamese wars | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

Co-belligerents: | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Tavoy column: Chiang Mai column: |

| ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

Including: 1 British sloop-of-war | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Initial invasion force:

Outer Ayutthaya: 50,000 [8] Siege of Ayutthaya: 40,000+ |

Initial defenses:

1 British sloop-of-war Outer Ayutthaya: 50,000 [8] Siege of Ayutthaya: unknown | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Unknown | Approximately 200,000 soldiers and civilians killed | ||||||||

The Burmese–Siamese War also known as the War of the second fall ( Thai: สงครามคราวเสียกรุงครั้งที่สอง, Burmese: ယိုးဒယား-မြန်မာစစ် (၁၇၆၅–၁၇၆၇)) was the second military conflict between Burma under Konbaung dynasty and Ayutthaya Kingdom under Siamese Ban Phlu Luang dynasty that lasted from 1765 until 1767, and the war that ended the 417-year-old Ayutthaya Kingdom. [9] Nonetheless, the Burmese were soon forced to give up their hard-won gains when the Chinese invasions of their homeland forced a complete withdrawal by the end of 1767. A new Siamese dynasty, to which the current Thai monarchy traces its origins, emerged to reunify Siam by 1771. [10] [11]

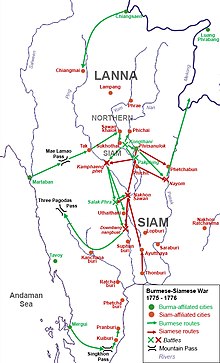

This war was the continuation of the 1759–60 war. The casus belli of this war was also the control of the Tenasserim coast and its trade, and Siamese support for rebels in the Burmese border regions. [12] [13] The war began in August 1765 when a 20,000-strong northern Burmese army invaded northern Siam, and was joined by three southern armies of over 20,000 in October, in a pincer movement on Ayutthaya. By late-January 1766, the Burmese armies had overcome numerically superior but poorly coordinated Siamese defenses, and converged before the Siamese capital. [9] [14]

The siege of Ayutthaya began during the first Chinese invasion of Burma. The Siamese believed that if they could hold out until the rainy season, the seasonal flooding of the Siamese central plain would force a retreat. But King Hsinbyushin of Burma believed that the Chinese war was a minor border dispute, and continued the siege. During the rainy season of 1766 (June–October), the battle moved to the waters of the flooded plain but failed to change the status quo. [9] [14] When the dry season came, the Chinese launched a much larger invasion but Hsinbyushin still refused to recall the troops. In March 1767, King Ekkathat of Siam offered to become a tributary but the Burmese demanded unconditional surrender. [5] On 7 April 1767, the Burmese sacked the starving city for the second time in its history, committing atrocities that have left a major black mark on Burmese-Thai relations to the present day. Thousands of Siamese captives were relocated to Burma.

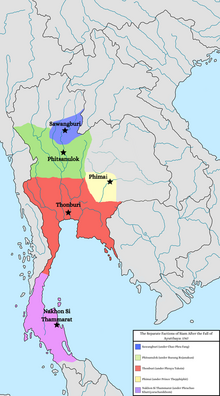

The Burmese occupation was short-lived. In November 1767, the Chinese again invaded with their largest force yet, finally convincing Hsinbyushin to withdraw his forces from Siam. In the ensuing civil war in Siam, the Siamese state of Thonburi, led by Taksin, had emerged victorious, defeating all other breakaway Siamese states and eliminating all threats to his new rule by 1771. [15] The Burmese, all the while, were preoccupied defeating a fourth Chinese invasion of Burma by December 1769.

By then, a new stalemate had taken hold. Burma had annexed the lower Tenasserim coast but again failed to eliminate Siam as the sponsor of rebellions in her eastern and southern borderlands. In the following years, Hsinbyushin was preoccupied by the Chinese threat, and did not renew the Siamese war until 1775—only after Lan Na had revolted again with Siamese support. The post-Ayutthaya Siamese leadership, in Thonburi and later Rattanakosin ( Bangkok), proved more than capable; they defeated the next two Burmese invasions ( 1775–1776 and 1785–1786), and vassalized Lan Na in the process.

Background

Rise of the Konbaung dynasty

With the weakening of centuries-old Burmese Toungoo dynasty by mid-eighteenth century, the Mons in Lower Burma were able to break free and form their own kingdom. The Mons elected the monk Smim Htaw Buddhaketi to be their king of their Restored Hanthawaddy Kingdom in 1740. [16] Smim Htaw, however, was deposed by a coup and replaced by his prime minister Binnya Dala in 1747 with Smim Htaw fleeing to Ayutthaya. [17] [18] Maha Damayaza Dipati, the last king of Toungoo dynasty, had authorities only in Upper Burma. Binnya Dala sent his brother Upayaza to lead Mon armies to conquer Upper Burma in 1751. [16] Upayaza was able to seize Ava, the Burmese royal capital, in 1752, capturing Maha Damayaza Dipati to Pegu and ending the Toungoo dynasty. [16]

When Ava was falling to the Mon invaders, a local village chief of Moksobo named U Aung Zeiya rallied Burmese patriots to rise against the Mons. [16] Aung Zeiya was enthroned as King Alaungpaya in 1752, founding the new Burmese Konbaung dynasty. [16] Siam took hostile attitudes towards the Mon kingdom, [17] [18] leading to the Mons being preoccupied with possible Siamese threats from the east and allowing Alaungpaya to gather his Burmese forces and consolidate in Upper Burma. Alaungpaya's son Thado Minsaw (later Hsinbyushin) retook Ava from the Mons in 1754. Alaungpaya mobilized his Burmese forces to invade Lower Burma in the same year, capturing Prome in 1755 and attacking Syriam, where British and French traders had been residing, [19] in 1756. Alaungpaya took Syriam in 1756 and killed French officials there for he was informed that the French had supported the Mons. [20] Alaungpaya also seized two French ships containing field guns, thousands of flintlock muskets and other ammunitions – a great haul to Burmese armory. [21] Alaungpaya then laid siege on Pegu, the Mon royal seat. The panicked Mon King Binnya Dala executed the former Burmese king Maha Damayaza Dipati, inadvertently giving Alaungpaya full legitimacy as the savior of Burmese nation. Alaungpaya seized Pegu in May 1757, [16] thus unifying Upper and Lower Burma under him. [17] Pegu was destroyed and the political administrative center of Lower Burma shifted from Pegu to Rangoon. [16]

In 1757, a British envoy from East India Company (EIC) arrived at the Burmese court to establish Anglo–Burmese relations. [16] The British also presented Alaungpaya with firearms and gunpowder. The Anglo–Burmese Treaty of 1757 granted Negrais and Bassein for the British to establish their trade factories. [16] The treaty also promised gunpower supply to Burma. [16] Next year, while Alaungpaya was on his campaign in Manipur, the Mons of Lower Burma stage rebellion in Pegu in 1758. [20] The Mon rebellion was soon put down by 1759. In 1759, the EIC ship Arcot, under the command of a sea captain named Whitehall, fired on Burmese targets at Rangoon. [19] [20] Whitehall was captured by the Burmese and sent to Alaungpaya. Whitehall was bailed out only by the payment of a heavy ransom. Alaungpaya was convinced that the British had supported and given firearms to the Mon rebels. He then decided to attack and occupy the town of Negrais (modern Hainggyi at the mouth of Pathein River), which had been under the control of the EIC since the Anglo-Siamese War in 1686. Ten Europeans and one hundred Indians in service of the EIC at Negrais were massacred by Burmese forces in late 1759 and the remaining survivors were taken to Upper Burma. [19] [20] Anglo–Burmese relations was put to halt for four decades until the mission of Michael Symes in 1795.

Internal developments of Ayutthaya

Burmese armies had not reached the outskirts of Ayutthaya since 1586 [22] and, after King Naresuan's victory over the Battle of Nong Sarai in 1593, there had not been serious threatening Burmese invasions since then. In the aftermath of Siamese Revolution of 1688, Phetracha ascended the throne and founded his Ban Phlu Luang dynasty [23] of the Late Ayutthaya Period, which was known for internal conflicts, including those in 1689, 1699, 1703 and 1733, owing to increasing powers of royal princes and nobility. [24] Phetracha faced undaunting rebellions at regional centers of Nakhon Ratchasima (Khorat) and Nakhon Si Thammarat (Ligor) in 1699–1700, [25] which took great efforts to quell. Siamese court of Late Ayutthaya, therefore, sought to decrease the powers of provincial governors. However, this reform became a failure and Ayutthayan court eventually lost effective control over its periphery. [24]

In pre-modern Siam, the military relied on conscripted levies as the backbone rather than professionally-trained personnel. In Late Ayutthaya Period, in early eighteenth century, Siam's rice export to Qing China grew. [23] Siam became a prominent rice exporter into China through Teochew Chinese merchants. [26] Siamese Phrai commonners of Central Siam, who cleared more lands and cultivated more rice [23] for exports, became enriched through this economic prosperity and they became less willing to participate in military conscription and corvée levies. The Phrai evaded conscription through capitation taxes or commodity taxes and outright absence [27] in order to partake in other more-profitable commercial activities. [23] This led to overall decline of effective manpower control of Siamese Ayutthayan royal court over its own subjects. When Dowager Queen Yothathep died in 1735, there was not enough men to parade her funeral [23] so King Borommakot had to relegate his own palace guards to join the procession. In 1742, the royal court managed to round up ten thousands of conscription evaders. [23] Suppression of local governors means that they were less-armed and unable to provide frontline defenses against external invaders. Chronic manpower shortage undermined Siam's defense system. [27] Government structure of Late Ayutthaya served to ensure internal stability and to prevent insurrections rather than to defend against invasions. [24] Internal rebellions were more of realistic and immediate threats than Burmese incursions, which had become something of distant past, to Siam. Decline of manpower control and compromised defense system that would eventually lead to the Fall of Ayutthaya in 1767 left Siam vulnerable and resulted from Siamese court being unable to adapt and reform in response to changes. [23]

Dynastic conflicts in Ayutthaya

Princely struggles began in 1755 when Prince Thammathibet, Borommakot's eldest son who had been the Wangna or Prince of the Front Palace and heir presumptive, arrested the servants of his half-brothers Chao Sam Krom or the Three Princes, who were sons of Borommakot born to secondary consorts rather than principal queens, for the princes' violation of ranks and honors. One of the Three Princes retaliated by informing Borommakot that Thammathibet had been in romantic relationships with two of the king's consorts. Borommakot punished Thammathibet by whipping with one hundred and eighty lashes of rattan blows, according to Siamese law. Thammathibet eventually succumbed to the wounds and died in 1756. [28] In 1757, Prince Thepphiphit, other son of Borommakot, in concert with high ministers of Chatusadom, proposed his father the king to make Prince Uthumphon the new heir. Uthumphon initially refused the position due to the fact that he had an older brother Prince Ekkathat. However, Borommakot intentionally passed over Ekkathat, citing that Ekkathat was incompetent [28] and sure to bring disaster to the kingdom. Borommakot forced his son Ekkathat to become a Buddhist monk to keep him away from politics and made his other son Uthumphon as the new Wangna in 1757.

Borommakot died in May 1758. The Three Princes laid their claims to the throne against Uthumphon and had their armies break into royal palace to seize the guns. Five senior Buddhist prelates then beseeched the Three Princes to cease their belligerent actions. The Three Princes complied and went to visit Uthumphon to pay obeisance. However, Ekkathat secretly sent policemen to arrest the Three Princes and had them executed. Uthumphon ascended the throne as the new king but faced political pressure from his elder brother Ekkathat, who defiantly stayed in royal palace not returning to his temple despite being a Buddhist monk. Uthumphon eventually gave in and abdicated in June 1758 after merely a month on the throne. [28] Ekkathat then eagerly left monkhood to take the throne as King Ekkathat the last king of Ayutthaya in 1758. Uthumphon became a monk at Wat Pradu Songtham Temple, earning him the epithet Khun Luang Hawat ('The King who seeks Temple'). In November 1758, Prince Thepphiphit, joined by other high-ranking ministers, came up with a conspiracy to overthrow Ekkathat in favor of Uthumphon. However, Uthumphon, not wanting the throne, chose to leak the seditious plot to Ekkathat himself. Ekkathat then had those conspiring ministers imprisoned and had his half-brother Thepphiphit board on a Dutch ship to be exiled to Sri Lankan Kingdom of Kandy. [28] Phraya Phrakhlang the Minister of Trade was also implicated. Phrakhlang managed to pay a large sum of money to the king to avoid punishments. Ekkathat not only spared Phrakhlang but also created him Chaophraya Phrakhlang the Samuha Nayok or Prime Minister.

Burmese invasion of 1760

In early eighteenth century, the Tenasserim Coast was divided between Burma and Siam, with Tavoy belonging to Burma and Siam having Mergui and Tenasserim. In 1742, in the face of Mon insurrection, the Burmese governors of Martaban and Tavoy took refuge in Siam. [18] Siam then took over the whole Tenasserim Coast. With Alaungpaya's conquest of Lower Burma in 1757, Tavoy returned to Burma. In 1758, Mon dissidents attacked Rangoon and Syriam but were repelled by the Burmese. [16] The Mons rebels took a French vessel to flee and ended up in the Siamese port of Mergui. Burma demanded that Siam hand over the Mon rebels but Siamese authorities refused, saying that it was a mere French merchant ship. Burma then took this Siamese stance as being supportive of Mon insurrections against Burma. Realizing that Burmese eastern frontiers would never be pacified with Siam advocating the Mon cause, Alaungpaya decided to attack Siam. [16] Tenasserim Coast then became Burmese–Siamese competing grounds.

Alaungpaya was also determined to conquer Siam as a part of Chakravartin concept of universal ruler to bring forth the new epoch of Maitreya Future Buddha. [29] Alaungpaya and his armies left Shwebo in mid-1759 to Rangoon, where he was informed that the Siamese attacked Tavoy and Burmese trade ships were seized by the Siamese in Tavoy. [30] Burmese vanguard, led by Minkhaung Nawrahta and the Prince of Myedu (Hsinbyushin) quickly took Mergui and Tenasserim in January 1760. King Ekathat sent an army under Phraya Yommaraj, with Phraya Phetchaburi Rueang as vanguard, to take position at the Singkhon Pass and another army under Phraya Rattanathibet as rearguard at Kuiburi. However, Phraya Yommaraj was defeated as the Burmese entered Western Siam. Phraya Rattanathibet sent his subordinate Khun Rong Palat Chu (ขุนรองปลัดชู) to face the Burmese at Wakhao Bay [31] on the shore of Gulf of Siam near modern Prachuap Khiri Khan but was defeated by the Burmese in the Battle of Wakhao. Siamese generals, who were apparently inept compared to their battle-hardened Burmese counterparts, completely fell back to Ayutthaya. The Burmese vanguard took Kuiburi, Pranburi, Phetchaburi, Ratchaburi and Suphanburi in rapid succession. [16] As the situation became critical, the panicked Ayutthayan court and people pleaded for the more-capable King Uthumphon to left monkhood to assume commands. Uthumphon sent Chaophraya Kalahom Khlongklaeb the Samuha Kalahom or Minister of Military with Siamese army to take position at Phakhai on the Talan River to the northwest of Ayutthaya. In the Battle of Talan, the Burmese vanguard was shelled by Siamese gunmen while crossing the river. Only when the main royal forces of Alaungpaya arrived in time to save the vanguard. [30] Kalahom Khlongklaeb and other Siamese commanders were killed in battle.

The Burmese reached the northwestern outskirts of Ayutthaya in April 1760 and took position at Bangban. Siamese boat people and foreign merchants moved to take refuge in the southern parts of the city moat. However, Burmese forces went to attack and massacre those refugees in the southern moat and plundering the area. Nicolas Bang, the Dutch opperhoofd of Ayutthaya, died from drowning while trying to escape the Burmese. [28] The Burmese mounted their cannons onto constructed towers to inflict fires onto Ayutthaya. The fires hit the Suriyat Amarin Palace, the royal residence of King Ekkathat, causing the palace spire to collapse. However, the time for the Burmese was running out as the wet rainy season approached that would turn Ayutthaya's suburbs into hostile swamps bred with diseases and discomfort. Thai chronicles stated that Alaungpaya was injured from an accidental cannon explosion, while Burmese chronicles stated that Alaungpaya fell ill with dysentery. [16] Nevertheless, Alaungpaya had to turn back, retreating through the Maesot Pass and eventually died from illness at Kinwya village, [16] halfway between Myawaddy and the Salween River, [32] in May 1760. [16] Siam was thus saved from Burmese conquest for one last time.

Interbellum events in Burma and Siam: 1760–1763

After the demise of Alaungpaya, his eldest son Naungdawgyi succeeded to the throne in 1760 as the new Burmese king but Burma descended into a short period of internal upheaval. Minkhaung Nawrahta, while returning from Siamese campaign as the rearguard, [32] passed through Toungoo where Thado Theinkathu the Prince of Toungoo, [30] who was a brother of Alaungpaya, attempted to arrest him by orders from the new king Naungdawgyi. [32] Minkhaung Nawrahta then arose in rebellion and seized Ava, only to be defeated and killed. [30] Thado Theinkathu also soon took up arms against his nephew Naungdawgyi but was also suppressed in 1762. [30] After these events, Burma became ready again for another round of military expeditions.

Ayutthaya was saved from Burmese conquest for one last time after the retreat of Alaungpaya in May 1760 and political conflicts resumed. The more-capable Uthumphon, the former king, had left monkhood to lead commands against the Burmese invasion of 1760. In June 1760, Uthumphon visited his brother Ekkathat on one day but found Ekkathat having bare sword laying on his laps – a gesture of political aggression and enmity. Uthumphon then decided to leave royal palace and politics to become Buddhist monk at Wat Pradu temple again in mid-1760, this time permanently. In February 1761, a group of 600 Mon refugees took up arms and rebelled against Siam, taking position at Khao Nangbuat Mountain in modern Sarika, Nakhon Nayok to the east of Ayutthaya. Ekkathat sent royal forces of 2,000 men under Phraya Siharaj Decho to deal with Mon rebels. The Mons, armed with only melee sharpened wooden sticks, managed to repel Siamese forces. Ekkathat had to send another regiment of 2,000 men under Phraya Yommaraj and Phraya Phetchaburi Rueang in order to successfully put down the Mon rebellion. This showed how ineffective the Siamese military forces had become by 1761.

Prince Thepphiphit, who had earlier been exiled to Sri Lanka after his failed rebellion in 1758, became involved in political conflicts in Sri Lanka. The Dutch conspired with native Sinhalese nobles, including the monks of Siam Nikaya sect, [33] to assassinate King Kirti Sri Rajasinha of Kandy and to replace him with the Siamese prince Thepphiphit in 1760. [28] [33] However, Kirti Sri Rajasinha became aware of the plot and drove Thepphiphit out of Sri Lanka. Thepphiphit ended up returning to Siam, arriving at the port of Mergui in 1762. [28] Ekkathat was shocked and enraged at the return of his fugitive half-brother and ordered his confinement in Tenasserim.

Dutch–Siamese relations had been in deterioration state due to Dutch trade in Siam being unprofitable and the Siamese court forcing the Dutch to pay Recognitiegelden or procession fees to Siamese trade officials. [28] The Dutch outright closed their factories at Ayutthaya, Ligor and left Siam in 1741. However, the Dutch decided to return and resume their trading post in Siam in 1748 for fear that the British would arrive and take over. [28] During this low ebb of Dutch–Siamese relations, the British stepped in. In 1762, George Pigot the governor of Madras and President of East India Company sent a British merchant William Powney (known in Thai chronicles as "Alangkapuni") [34] to Ayutthaya in order to renew relation with Siam. Powney presented King Ekkathat with a lion, an Arabian horse, an ostrich and proposed to establish a British outpost in Mergui. [34]

In late 1763, a Burmese governor named Udaungza rose up and seized power in Tavoy, killing the Konbaung-appointed Tavoy governor. Udaungza then proclaimed himself the governor of Tavoy and sent tributes to submit to Siam. Tavoy and Tenasserim Coast returned to Siamese rule again after this incident.

Burmese conquests of Lanna and Laos

Burmese conquest of Lanna (1763)

After the Burmese conquest of Lanna in 1558, Lanna or modern Northern Thailand had been mostly under Burmese rule. At the time when the Burmese Toungoo dynasty became weak, Ong Kham, the former Tai Lue king of Luang Prabang, expelled the Burmese from Chiang Mai in 1727 and made himself the King of Chiang Mai [35] as an independent sovereign. The rest of Lanna soon followed and Burma lost control over the region but Lanna became fragmented into individual princedoms. Ong Kham of Chiang Mai died 1759, to be succeeded by his son Ong Chan. [35] However, Ong Chan was deposed by his brother in 1761 who gave the throne to a Buddhist monk instead. In 1762, King Naungdawgyi of Burma recalled that the fifty-seven towns of Lanna used to be under Burmese suzerainty and sought to bring Lanna back under Burmese control. [30] Naungdawgyi sent Burmese army under Abaya Kamani, with Minhla Thiri (later Maha Nawrahta) as second-in-command, with the forces of 7,500 men to conquer Chiang Mai in October 1762. [30] Abaya Kamani reached Chiang Mai in December, taking position at Wat Kutao and laying siege on Chiang Mai. Chiang Mai requested supports from King Ekkathat of Ayutthaya. Chiang Mai persisted many months until August 1763 [36] when Chiang Mai fell to the Burmese invaders. Ekkathat sent Chaophraya Phitsanulok Rueang the governor of Phitsanulok to bring Siamese forces to rescue Chiang Mai but he was too late as Chiang Mai had already fallen to the Burmese so the Siamese turned back.

King Naungdawgyi died in December 1763 and was succeeded by his brother the Myedu Prince who became King Hsinbyushin. [30] Abaya Kamani deported nearly the whole Northern Thai population of Chiang Mai, including the former king Ong Chan and Smim Htaw the former king of Pegu, to Burma in 1764. The new king Hsinbyushin appointed Abaya Kamani to be the Myowun or Burmese governor of Chiang Mai and elevated Minhla Thiri to become Maha Nawrahta. [30] However, Lanna soon broke out in rebellion against Burma in 1764 under leaderships of Saen Khwang in Phayao and Nwe Mano in Lamphun. Hsinbyushin was determined to complete the unfinished mission of his father Alaungpaya in the conquest of Siam so initiated a grand campaign to accomplish his goal in 1764. He sent 20,000-men-strong army, under the command of Nemyo Thihapate, the Burmese commander who had a Lao (Lanna) mother according to a Thai chronicle composed in 1795, to conquer Lanna, Laos and then went on to conquer Siam. Nemyo Thihapate left for Lanna in February 1764, [30] defeating Saen Khwang near Chiang Saen and Nwe Mano at Lamphun. Nemyo Thihapate also took Lampang, installing Chaikaew (father of Kawila) as the ruler of Lampang. After pacifying Lanna, as the rainy season arrived, Nemyo Thihapate and his Burmese forces rested and sheltered at Nan.

Burmese conquest of Laos (1765)

Since early eighteenth century, the Lao kingdom of Lanxang had fragmented into three separate kingdoms of Luang Prabang, Vientiane and Champasak. Lao kingdoms of Luang Prabang and Vientiane had been engaging in political rivalry. In October 1764, King Ong Boun of Vientiane wrote a letter to King Hsinbyushin, urging the Burmese to invade his rival Luang Prabang. After sheltering for wet season at Nan in 1764, Nemyo Thihapate and his Burmese army set off to conquer Luang Prabang. The Burmese left Nan in November 1764 to reach Luang Prabang. [30] [37] King Sotikakumman of Luang Prabang and his brother Prince Surinyavong led Lao army of 50,000 men [37] to face the Burmese on the banks of Mekong. However, in the Battle of Mekong, the Lao were soundly defeated and had to retreat into the city. Nemyo Thihapate reminded his soldiers that the goal of this campaign was not only to conquer Lanna and Laos but also to conquer Ayutthaya so they should not waste much time and should take Luang Prabang with urgency. [30] [37] Luang Prabang fell to the Burmese in March 1765. [29] [37] Sotikakumman had to give away his daughter, other Lao noblewomen and servants to the Burmese court. [30] His brother Surinyawong was also captured as prisoner-of-war and hostage.

After Burmese victory at Luang Prabang, King Ong Boun of Vientiane submitted his kingdom to Burmese rule. Lao kingdoms of Luang Prabang and Vientiane (not including the Kingdom of Champasak) then became Burmese vassals in 1765 and would remain so until the Siamese conquest of Laos in 1778–1779. After the Luang Prabang campaign, Nemyo Thihapate and his army went to pacify Kengtung and then took the wet season shelter at Lampang, [30] contemplating for the invasion of Siam by the end of that year.

Burmese preparations

Cause of the war

At his ascension in 1764, the new Burmese king Hsinbyushin was determined to accomplish the unfinished mission of his father King Alaungpaya to conquer Ayutthaya. Hsinbyushin had wanted to continue the war with Siam since the end of the last war. [38] The Burmese–Siamese War (1765–1767) was the continuation of the war of 1759–1760, the casus belli of which was a dispute over the control of the Tenasserim coast and its trade, [39] and Siamese support for ethnic Mon rebels of the fallen restored Hanthawaddy Kingdom of Lower Burma. [40] The 1760 war, which claimed the life of the dynasty founder King Alaungpaya, was inconclusive. Although Burma regained control of the upper Tenasserim coast to Tavoy, it achieved none of its other objectives. In the Burmese south, the Siamese readily provided shelter to the defeated ethnic Mon rebels.

Burmese strategy

As the deputy commander-in-chief in the 1760 war, Hsinbyushin used his first hand experience to plan the next invasion. His general plan called for a pincer movement on the Siamese capital from the north and the south. [13] The Burmese battle plan was greatly shaped by their experience in the 1759–1760 war. First, they would avoid a single pronged attack route along the narrow Gulf of Siam coastline, which they discovered, could easily be clogged up by more numerous Siamese forces. In 1760, the Burmese were forced to spend nearly three months (January–March) to fight their way out of the coastline. [41] This time, they planned a multi-pronged attack from all sides to stretch out the numerically superior Siamese defenses. [13]

Secondly, they would start the invasion early to maximize the dry-season campaign period. In the previous war, Alaungpaya started the invasion too late (in late December 1759/early January 1760). [42] When the Burmese finally reached Ayutthaya in mid April, they only had a little over a month left before the rainy season to take the city. This time, they elected to begin the invasion at the height of the rainy season. By starting the invasion early, the Burmese hoped, their armies would be within a striking distance from Ayutthaya at the beginning of the dry season. [43]

Burmese preparations

After sending Nemyo Thihapate to Lanna in late 1764, Hsinbyushin dispatched another army of 20,000 men led by Maha Nawrahta to Tavoy in December 1764 (8th waxing of Nadaw 1126 ME), [44] with Nemyo Gonnarat and Tuyin Yanaunggyaw as seconds-in-command [30] and with Metkya Bo and Teingya Minkhaung as vanguard. The Burmese artillery corps were led by a group of about 200 French soldiers who were captured in the Battle of Syriam in 1756 during the Burmese civil war of 1752–1757. Simultaneously, while the main Burmese armies were being massed at the Siamese border, a rebellion broke out in Manipur. Characteristically, Hsinbyushin did not recall the armies. Instead, the Burmese king himself led his army to subjugate Manipur in December 1764, capturing the Manipuri capital of Imphal and deported Manipuri population to settle in Burma. [45]

Burmese conquests of Lanna and Laos in 1762–1765 allowed Burma to access food and manpower resources that were later proven to be crucial to the Ayutthaya campaign. Ne Myo Thihapate was ordered to raise an army from the Shan States throughout 1764. By November, Ne Myo Thihapate commanded a 20,000-strong army at Kengtung, preparing to leave for Chiang Mai. As was customary, the Shan regiments were led by their own saophas (chiefs). [6] (Not everyone was happy about the Burmese army's conscription drive, however. Some of the saophas of northern Shan states, which at the time paid dual tribute to Burma and China, fled to China, and complained to the Chinese emperor). [46] [47] Nemyo Thihapate rested his armies in Lampang for the rainy season of 1765, preparing for the upcoming invasion of Siam.

Burmese invasion of Western Siam

Burmese conquest of Tenasserim

Tenasserim Coast came under Siamese domination again in late 1763 due to defection of Udaungza the self-proclaimed governor of Tavoy. Maha Nawrahta and his armies left Burma in December 1764, [30] reaching Martaban. Maha Nawrahta sent his vanguard of 5,000 men to take Tavoy in January 1765. Udaungza took refuge in Mergui. Maha Nawrahta sent a ship to Mergui, asking for the surrender of Udaungza. When Siamese authorities did not comply, Maha Nawrahta then quickly took Mergui and Tenasserim on January 11, 1765, massacring the population who failed to escape. [28] Ayutthaya received the news of Burmese conquest of Tenasserim with consternation as the royal court prepared for defense of the capital. [28]

In April 1765, King Hsinbyushin moved his royal seat to Ava, the traditional Burmese capital. He also reinforced Maha Nawrahta with additional forces of 10,000 men including; [30]

- Pegu regiment; 3,000 men, under Einda Yaza

- Martaban regiment; 3,000 men, under Binnya Sein

including the newly-recruited forces from Tenasserim;

- Tavoy regiment; 2,000 men, under governor of Martaban

- Mergui and Tenasserim regiment; 2,000 men, under Lakyawdin

This, combined with the original number of 20,000 men, made the total forces of 30,000 men [48] under Maha Nawrahta. The Burmese army now had mobilized 50,000 men, including those in Lanna. (This likely represented the largest mobilization of the Burmese army since Bayinnaung's 1568–1569 invasion.). [49]

Burmese invasion of Western Siam

Thai, French and Dutch sources state that the Burmese forces invaded Western Siam in early 1765. Udaungza the fugitive former governor of Tavoy fled from Tenasserim down south to Kra Isthmus to Kraburi. [50] The Burmese were keen on chasing after Udaungza and then followed Udaungza to Kraburi, burning down the town. The Tavoy governor fled further to Phetchaburi, where Prince Thepphiphit also took refuge. The Burmese forces sacked and burnt down the Siamese towns of Chumphon, Pathio, Kuiburi and Pranburi on the way and then returned to Tavoy via the Singkhon Pass.

King Ekkathat arranged for Prince Thepphiphit to be grounded in Chanthaburi and Udaungza to reside in Chonburi on Eastern Siamese Coast. The Siamese king then sent out forces to halt Burmese advances;

- Chaophraya Phrakhlang the Samuha Nayok or Prime Minister, accompanied by Phraya Yommaraj and Phraya Tak, led the forces of 15,000 men [50] including armored elephants and mounted cannons to deal with the Burmese at Phetchaburi and Ratchaburi.

- Chaophraya Nakhon Si Thammarat the governor of Nakhon Si Thammarat (Ligor) led Southern Siamese forces to defend the Singkhon Pass against possible Burmese incursion from Tenasserim.

- Phraya Kalahom the Samuha Kalahom of Minister of Military led Siamese forces to the Three Pagodas Pass, where the Burmese did not come, showing the inaccuracy of Siamese intelligence system.

- Phraya Phetchaburi Rueang the governor of Phetchaburi led Siamese army north to Sawankhalok to defend against Burmese invasion from Lanna.

- Phra Phirenthorathep stationed his troops at Kanchanaburi.

In May 1765, Maha Nawrahta at Tavoy sent his vanguard forces of 5,000 men under Metkya Bo and Teingya Minkhaung passing through the Myitta Pass to attack Kanchanaburi. Phra Phirenthorathep at Kanchanaburi, with his 3,000 men, was defeated and retreated. The Burmese vanguard then quickly conquered Western Siamese cities. By this point, the Ayutthayan royal government had lost any controls over its peripheral cities, which were left at the mercy of the Burmese. The Burmese invaders took reconciliatory approach to these outlying Siamese towns. Towns that brought no resistances were spared from destruction and surrendered Siamese leaders were made to swear loyalty. [30] Any cities that resisted and took up arms against Burmese invaders would face military punishment and subjugation.

The main Siamese forces of Chaophraya Phrakhlang met with the Burmese vanguard at Ratchaburi, leading to the Battle of Ratchaburi. The Siamese in Ratchaburi resisted for many days. Siamese elephant mahouts intoxicated their elephants with alcohol in order to make them more aggressive but one day this intoxication went too far as the elephants became uncontrollable, [50] leading to Siamese defeat and Burmese capture of Ratchaburi. Western Siamese towns of Ratchaburi, Phetchaburi, Kanchanaburi and Chaiya all fell to the Burmese. Siamese people in these fallen cities fled into the jungles in large numbers as they were hunted down and captured by the invaders.

After conquering Western Siam, the Burmese vanguard encamped at Kanchanaburi in modern Tha Maka district where the two rivers ( Khwae Yai and Khwae Noi) met, while Maha Nawrahta himself was still in Tavoy. Maha Nawrahta also organized Western Siamese captives from Phetchaburi, Ratchaburi, Kanchanaburi, Suphanburi, Chaiya and Chumphon into regiments placed under the rearguard of Mingyi Kamani Sanda [30] the Wun of Pagan. French and Dutch sources stated that all cities to the west of Ayutthaya had fallen under Burmese control by early 1765. [28] Abraham Werndlij, the new Dutch opperhoofd of Ayutthaya, expressed his concerns that Siam was unable to do anything and left the Burmese to occupy Western Siam, which was the sources of Dutch commodities including sappanwood and tin. [28]

The main reason for the quick fall of Kanchanaburi could be that the Burmese were battle-hardened. But it could also be that the Siamese command miscalculated where the Burmese main attack would come from, and had not sufficiently reinforced the fort to withstand a major attack. Judging by the Siamese chronicles' reporting of the main attack route, the Siamese command appeared to have believed that the main Burmese attack would come from the Gulf of Siam coastline, instead of the most obvious and shortest route via Kanchanaburi. The Siamese sources say that Maha Nawrahta's main invasion route came from southern Tenasserim, crossing the Tenasserim range at Chumphon and Phetchaburi. [51] [52] The path is totally different from the Kanchanaburi route reported by the Burmese chronicles. Historian Kyaw Thet specifically adds that the main attack route was via the Myitta Pass. [7]

- The Chumphon route is unlikely to have been the main attack route as it was even farther south than Alaungpaya's Kui Buri route. It means the Burmese would have had a longer route to go back up the Gulf of Siam coast. Without the element of surprise that Alaungpaya enjoyed in the 1760 war, the Burmese invasion force of 1765 would have had to fight more than three months it took Alaungpaya to break away from the coast. Yet, Maha Nawrahta's army was west of Ayutthaya by December. To be sure, the smaller Burmese army that took Tenasserim could have crossed over at Chumphon, and marched up the coast although the most southerly battles reported by the Burmese were at Ratchaburi [53] and Phetchaburi, [6] on the northern coast. At any rate, according to the Burmese sources, Chumphon was not the main attack route

Siamese preparations

As the Burmese had occupied all of Western Siam by early 1765 encamping at Kanchanaburi, King Ekkathat organized Siamese forces of 15,000 to 16,000 men [28] to spread out to defend against Burmese invaders in June 1765;

- Chaophraya Nakhon Si Thammarat the governor of Ligor (which was the administrative center of Southern Siam) stationed his Southern Siamese troops of 1,000 men at Bang Bamru just to the south of Burmese-occupied Ratchaburi.

- Chaophraya Phitsanulok Rueang the governor of Phitsanulok (which was the administrative center of Northern Siam) took position of his Northern Siamese forces at Wat Phukhaothong temple to the northwest of Ayutthaya.

- Phraya Nakhon Ratchasima the governor of Nakhon Ratchasima led his Khorat troops to take position at Wat Chedi Daeng temple to the north of Ayutthaya.

- Phraya Rattanathibet the Minister of Palace Affairs led the Khorat forces of 4,000 men to take position at Thonburi to the south of Ayutthaya to prevent Burmese riverine advances through the Chao Phraya River. An iron chain was erected across the river to obstruct the Burmese fleet. [28]

- Phraya Yommaraj the Head of Police Bureau, with 2,000 men, stationed at Nonthaburi.

Wet Season Campaign (August–October 1765)

Southern Front: Battle of Thonburi

By mid-1765, Maha Nawrahta the commander of the Burmese Tavoy column had still been in Tavoy, while his vanguard had already encamping at Kanchanaburi. In August 1765, the Burmese vanguard at Kanchanaburi, led by Metkya Bo, attacked and repelled the Southern Siamese forces under the governor of Ligor at Bang Bamru. Suffering the defeat, the Ligor governor was then charged with incompetency, arrested and imprisoned in Ayutthaya. Metkya Bo and Teingya Minkhaung led their Burmese vanguard to proceed to attack Thonburi. The panicked Siamese commander Phraya Rattanathibet abandoned his position and retreated with his Khorat regiment technically dispersed. The Burmese vanguard seized the French-constructed Wichaiyen Fort at Bangkok. French Catholic seminary and Dutch trade factory at Thonburi were also burnt down and destroyed. [28] After successful capture of Thonburi, the Burmese vanguard then returned to the position at Kanchanaburi.

Northern Front: Burmese invasion of Northern Siam

Burmese territory

Siamese territory

After subjugating Lanna and Laos, Nemyo Thihapate and his Burmese forces took rainy season shelter in Lampang. Conquest of Lanna and Laos allowed the Burmese to access vast manpower and other resources to be utilized in their invasion of Siam from the north. In mid-1765, Nemyo Thihapate recruited local Lanna and Lao men into regiments, adding to the total of 43,000 men, 400 elephants, 1,200 horses and 300 riverine vessels alongside the existing Burmese forces; [30]

- The Lanna (Yun) regiments, under the command of Thado Mindin (who later became the Burmese governor of Chiang Mai in 1769), composing of 12,000 men, 200 elephants and 700 horses, were recruited from Chiang Mai, Lampang, Lamphun, Chiang Saen, Nan, Phrae, Chiang Rai, Phayao, Chiang Khong, Mong Hsat, Mongpu, Kenglat and Mongnai.

- The Lanxang (Linzin) regiments, under the command of Thiri Yazathingyan, composing of 8,000 men, 100 elephants and 300 horses, were recruited from Luang Prabang, Vientiane, Muang La, Mong Yawng and Mong Hang.

- Burmese riparian fleet, composing of 10,000 men and 300 boats under leadership of Tuyin Yamagyaw.

Nemyo Thihapate and his Burmese-Lanna-Lao forces left Lampang on 23 August 1765 (8th waxing of Tawthalin 1127 ME) [44] at the height of the rainy season down the Wang River to attack Hua Mueang Nuea or Northern Siam. The reason for the earlier start of the northern army was that it was much farther away from Ayutthaya than its southern counterparts. Still the strategy did not work as planned. Like Maha Nawrahta, Nemyo Thihapate sent his vanguard forces of 5,000 men under Satpagyon Bo to do the initial conquests. Satpagyon Bo met Phraya Phetchaburi Rueang the commander of northern Siamese defense forces at Sawankhalok, leading to the Battle of Sawankhalok. Sawankhalok resisted for many days but was eventually conquered by the Burmese commander Satpagyon Bo and Phraya Phetchaburi Rueang had to retreat south to Chainat.

Siamese initial defeat at Sawankhalok left the whole Northern Siam vulnerable to Burmese conquests. After Sawankhalok, Satpagyon Bo attacked Sukhothai and Tak, where the governor Phraya Tak was called to Ayutthaya leaving little defense to the town. Tak offered resistance but eventually fell to the Burmese commander Satpagyon Bo. After Tak, Satpagyon Bo proceeded to attack Kamphaeng Phet, which offered no resistances. Burmese invading forces in the northern front implemented in the same policy as in the southwestern front in regard to peripheral Siamese cities, in which the cities that surrendered would be spared from destruction but any cities that resisted would face punishment. The northern army's advance was greatly slowed by the rainy weather and the "petty chiefs" who put up a fight, forcing Thihapate to storm town after town. [6] [43] Nonetheless, the Burmese vangaurd fought the way down the Wang, finally taking Tak and Kamphaeng Phet by the end of the rainy season. [53]

Dry Season Campaign (October 1765–January 1766)

Southern Front: Battle of Nonthaburi

Maha Nawrahta himself marched his main forces from Tavoy to Kanchanaburi, leaving Tavoy on October 23, 1765 (10th waxing of Tazaungmon 1127 ME) [54] in three directions. He had 20,000 to 30,000 under his command. (The Burmese sources say 30,000 men including 2000 horses and 200 elephants [54] but G E Harvey gives the actual invasion force as 20,000. [6] At least part of the difference could be explained by the rearguard who stayed behind to defend the Tenasserim coast). A small army invaded by the Three Pagodas Pass towards Suphan Buri. Another small army invaded down the Tenasserim coast towards Mergui (Myeik) and Tenasserim (Tanintharyi) town. However, the main thrust of his attack was at Kanchanaburi. [43] His 20,000-strong main southern army invaded via the Myitta Pass. (It was also the same route the Japanese used in 1942 to invade Burma from Thailand.) Kanchanaburi fell with little resistance. [7]

In 1765, the British trader William Powney (called Alangkapuni in Thai sources) sailed his merchant ship to Ayutthaya, [34] bringing Indian textiles to sell. However, his business was unsuccessful apparently because Siam had been in the middle of warfare and no one was bothered to buy luxurious goods. Powney instead was caught in the indigenous warfare as King Ekkathat, through his minister Chaophraya Phrakhlang, requested for the aid from Powney to defend against the Burmese invasion, in which Powney agreed on conditions that the Siamese court should provide him with adequate resources. [34] Powney then sailed downstream from Ayutthaya and anchored his brigantine at Thonburi to halt Burmese advances. Abraham Werndlij, the Dutch opperhoofd, was very concerned about the prospect that Ayutthaya royal city would again be attacked by the Burmese, as fresh memory of the death of the previous opperhoofd in 1760 and the loss of commodity goods were still looming. [28] In October 1765, a Dutch diplomatic ship arrived in Ayutthaya from Batavia, giving instructions to Werndlij to secretly close down and abandon the Dutch factory in Ayutthaya to escape Burmese attacks. Werndlij, with the ship carrying as many Dutch goods as possible, hurriedly left Ayutthaya on October 28. [28] After resting at the mouth of Chao Phraya River, Werndlij and his Dutch ship left Siam in early November 1765, [28] ending Ayutthaya–Dutch relations.

In December 1765, Maha Nawrahta at Kanchanaburi sent his vanguard under Metkya Bo to occupy Thonburi again, reaching Thonburi on December 24. Metkya Bo took position at the Wichayen Fort in Bangkok, mounting his cannon to fire on Powney's brigantine warship at Thonburi, prompting Powney to retreat to Nonthaburi. The Siamese commander Phraya Yommaraj at Nonthaburi abandoned his position and retreated in panic, leaving Powney alone to fight the Burmese. Metkya Bo then proceeded to take position and encamp at Wat Khema Phitaram temple in Nonthaburi, about 60 km south of Ayutthaya, on both banks of the Chao Phraya River. Powney requested for more firearms and ammunition from the Siamese royal court. [34] Ayutthayan court agreed to send supplies but Powney had to deposit his trade goods [34] in the Phra Klang Sinkha or Royal Warehouse in exchange – the condition that Powney only reluctantly complied.

The Burmese finally faced a serious Siamese defensive line guarding the route to the capital. On one night, Powney and his Siamese allies sailed down to make a joint land-naval attack on the Burmese garrison at Nonthaburi by surprise, leading to the Battle of Nonthaburi in December 1765 – the first major battle of the southern theatre. The Burmese suffered losses but also feigned retreat. The unsuspecting Siamese soldiers along with a number of British traders entered Nonthaburi without caution, where they were ambushed and routed by the Burmese. [34] The Burmese put the decapitated head of a British supercargo on a pike for display. Defeated, Powney pressed for more guns, boats and personnel from Ayutthaya through Chaophraya Phrakhlang but this time his demands were not met due to the Siamese court being low in resources and did not fully trust Powney. Powney was dissatisfied about Siam [34] not complying to his demands so he decided to turn against Siam. Powney abandoned his position and eventually left Siam, leaving his cargo behind in Ayutthaya and plundering six Chinese–Siamese junks on the way.

Northern Front: Battle of Sukhothai

Green represents the Burmese.

Magenta shows the trail of Ayutthayan captives being deported to Burma.

Chaophraya Phitsanulok Rueang, who had been in command of Northern Siamese regiment at Wat Phukhaothong temple in Ayutthaya, in the middle of warfare, gained permission from King Ekkathat to return to Phitsanulok to attend his mother's funeral, leaving his subordinate Luang Kosa to be in charge. [50] In October 1765, the Burmese vanguard under Satpagyon Bo attacked Sukhothai and took the city. The Siamese had to initially abandon their city and returned to lay siege on the Burmese-occupied Sukhothai, leading to the Battle of Sukhothai. Chaophraya Phitsanulok brought forces from his base in Phitsanulok to participate in the siege of Sukhothai.

In November 1765, Prince Chaofa Chit, who had been a political prisoner inside of the Ayutthayan palace, broke free and went to visit Uthumphon [28] the temple king at Wat Pradu Songtham temple with the help of Luang Kosa of Phitsanulok. This political incident put the Siamese royal court in commotion. Luang Kosa then took Prince Chit north to Phitsanulok, where Chaophraya Phitsanulok the governor was absent and away fighting the Burmese at Sukhothai. Prince Chit then decided to seize power and establish himself in Phitsanulok, fortifying himself against King Ekkathat. Lady Chuengchiang, wife of Chaophraya Phitsanulok, escaped in a small boat to inform her husband at Sukhothai about the coup of Prince Chit in Phitsanulok. Chaophraya Phitsanulok was so enraged that he decided to abandon his campaign in Sukhothai and returned to Phitsanulok, bringing his forces to subjugate Prince Chit. [50] Battle ensued between Chaophraya Phitsanulok and Prince Chit in Phitsanulok and this distraction allowed the Burmese to proceed. Eventually, Chaophraya Phitsanulok was able to retake his city, capturing the fugitive Prince Chit. Chaophraya Phitsanulok then had Prince Chit executed by drowning.

Ne Myo Thihapate's northern army was stuck in northern Siam although the pace of his advance had improved considerably since the end of the rainy season. After taking Kamphaeng Phet, Thihapate turned northeast, and captured the main northern cities of Sukhothai and Phitsanulok. Burmese chronicles states that the Burmese army took Phitsanulok by force, occupying Phitsanulok as the base for months. [30] However, Thai chronicles describes that Nemyo Thihapate went directly from Sukhothai to Kamphaeng Phet in January 1766 without taking Phitsanulok, presuming that Chaophraya Phitsanulok retained his position in Phitsanulok as he would later survive to become one of the regional regime leaders after the Fall of Ayutthaya. At Phitsanulok, Nemyo Thihapate paused to refill the ranks because in about 4 months, he had already lost many men to the grueling campaign and to "preventable diseases". The local chiefs were made to drink the water of allegiance and provide conscripts to the Burmese army. (Outside Ayutthaya, Maha Nawrahta too was collecting local levies.) [43] [55]

While the Burmese refilled their ranks, the Siamese command belatedly sent another army to retake Phitsanulok. But the Siamese army was driven back with heavy losses. It was the last major stand by the Siamese in the north. The Siamese defense collapsed afterwards. Nemyo Thihapate sent his two commanders Thiri Nanda Thingyan and Kyawgaung Kyawthu to finish up the remaining Northern Siamese towns of Phichai, Phichit, Nakhon Sawan and Ang Thong. [30] The Burmese army moved by boat down the Nan River, taking Phichai, Phichit, Nakhon Sawan, and down the Chao Phraya, taking Ang Thong. [52] Captured Siamese cannons and firearms were sent to Burmese-held Chiang Mai to be stocked. [30] Nemyo Thihapate also organized Northern Siamese men from Tak, Kamphaeng Phet, Sawankhalok, Sukhothai, Phitsanulok, Phichai, Phichit, Nakhon Sawan and Ang Thong into new regiments under the vanguard command of Nanda Udein Kyawdin. [30]

Western Front: Battle of Siguk

In early 1766, King Ekkathat sent Phraya Phollathep the Minister of Agriculture to lead Siamese forces, which the Burmese chronicles describes as having up to 60,000 men with 500 elephants and 500 cannons, [30] to station at Siguk (Thigok in Burmese, in modern Nam Tao, Bang Ban, Ayutthaya) about ten kilometers to the west of Ayutthaya.

Maha Nawrahta at Kanchanaburi proceeded towards Ayutthaya in January 1766, dividing his armies into two routes; [30]

- The first route, the land armies taken by Maha Nawrahta himself, would march through Suphanburi to approach Ayutthaya from the west.

- The second route, the riparian fleet led by Mingyi Kamani Sanda, sailed through Thonburi and Nonthaburi on the Chao Phraya River, approaching Ayutthaya from the south.

Maha Nawrahta and his main forces met the Siamese force of 60,000 men under the command of Chaophraya Phollathep at Siguk to the west of Ayutthaya, leading to the Battle of Siguk. Outnumbered 3 to 1, the more experienced Burmese army nonetheless routed the much larger Siamese army, which according to the Burmese, was "chopped to pieces", [56] forcing the remaining Siamese troops to retreat to the capital. [5] Maha Nawrahta had now arrived at Ayutthaya as planned, in record time. ("It took Alaungpaya's 40,000 men about three and a half months to arrive at Ayutthaya in 1760 whereas it took Maha Nawrahta's 20,000 plus army just about two months"). But he pulled back to the northwest of the city because he did not see Thihapate's northern army, and because he did not want to take on another major battle with his depleted army. He used the hiatus to refill the ranks with Siamese conscripts. [55]

Burmese Approach onto Ayutthaya

Mingyi Kamani Sanda and his fleet proceeded through the Chao Phraya River and took position at Bangsai (in modern Bang Pa-in district), about five kilometers to the south of Ayutthaya where the main Ayutthayan waterway checkpoint stood. After the victorious Battle of Siguk, Maha Nawrahta informed King Hsinbyushin at Ava that he had conquered all cities to the west of Ayutthaya and had already taken position in the outskirts of Ayutthaya, [30] waiting for Nemyo Thihapate to join from the north. King Hsinbyushin appointed Mingyi Manya to be the new governor of Tavoy to replace Udaungza, signifying long-term Burmese control of Tavoy. The Burmese king also sent a Mon regiment of 2,000 men under the command of Binnya Sein to join as an additional force. From Ang Thong, Nemyo Thihapate marched his army through the old route of Chao Phraya River that would become modern Khlong Bangkaeo canal from Ang Thong to Ayutthaya (Old route of Chao Phraya River was inadvertently diverted through a digging of a new canal from Ang Thong to Pamok. The old route gradually dried out in favor of the new route and became a smaller Bang Kaeo canal by Early Bangkok Period.). Nemyo Thihapate reached the environs of Ayutthaya on 20 January 1766 (5th waxing of Tabodwe 1127 ME), [30] making contact with Maha Nawrahta's army. [43] Nemyo Thihapate took position at Paknam Prasop (Panan Pathok in Burmese, modern Bang Pahan district), about seven kilometers to the north of Ayutthaya.

By January 1766, all of the main Burmese forces, including both Tavoy and Chiang Mai columns, approached Ayutthaya in three directions;

- Nemyo Thihapate, with his Burmese-Lanna-Lao forces of 20,000 men, encamped at Paknam Prasop to the north of Ayutthaya.

- Maha Nawrahta, with his 20,000-30,000 men, encamped at Siguk to the west of Ayutthaya.

- Mingyi Kamani Sanda stationed his fleet at Bangsai to the south of Ayutthaya, under the command of Maha Nawrahta. He was joined by the Mon regiment of Binnya Sein.

Battle at the outskirts (January 1766)

Northern Front: Battle of Paknam Prasop

In January 1766, when the main Burmese Chiang Mai column of Nemyo Thihapate was approaching Ayutthaya via the old route of Chao Phraya River, King Ekkathat sent Siamese armies, both by land and rivers, under Chaophraya Phrakhlang the Prime Minister with 10,000 men (50,000 men according to Burmese chronicles) [30] to halt the advancing Burmese at Paknam Prasop (Panan Pathok in Burmese) to the north of Ayutthaya. Nemyo Thihapate met the Siamese armies at about two and a quarter miles [30] northwest from Paknam Prasop on the Lopburi River, leading to the Battle of Paknam Prasop in January 1766. Thai chronicles emphasized the undisciplined ineffectiveness of Siamese military. Nemyo Thihapate totally defeated the Siamese armies of Phrakhlang in this battle, inflicting heavy casualties and losses on Siamese side. Phrakhlang and the remaining of his armies retreated into Ayutthaya. Nemyo Thihapate was then able to proceed and establish himself at Paknam Prasop to the north of Ayutthaya. 1,000 Siamese soldiers, 200 elephants, 500 guns and 300 small boats were captured by the Burmese. [30]

Three days after the first Siamese defeat at Paknam Prasop, King Ekkathat sent another army under Chaophraya Phrakhlang with 10,000 men in a new attempt to dislodge the Burmese from Paknam Prasop in January 1766. This time, a number of Ayutthayan city dwellers even followed the Siamese armies to the battle only to watch the Burmese-Siamese battle out of curiosity. Nemyo Thihapate led his Burmese army of 10,000 men, 100 elephants and 1,000 horses to engage with the Siamese. [30] According to Thai chronicles, Nemyo Thihapate lured the Siamese into thinking that he was going to retreat. The unsuspecting Siamese charged directly into Burmese standing at Paknam Prasop, only to be ambushed and overwhelmed from the flanks. The Siamese again suffered heavy losses and defeat for the second time at Paknam Prasop, with dead bodies of Siamese soldiers scattering on the battlefield. Curious Ayutthayan battle spectators were also killed. The Burmese captured 1,000 Siamese personnel and 100 of Siamese elephants as war spoils. [30]

Western Front: Battle of Wat Phukhaothong

Five days after Siamese defeat at Paknam Prasop, in late January 1766, the Siamese made another attempt to attack the Burmese at the outskirts. King Ekkathat made a last-ditch effort to prevent a siege of the city by sending two armies of 50,000 men, 400 elephants and 1,000 guns [30] under Phraya Phetchaburi Rueang (called Bra Than in Burmese chronicles) the governor of Phetchaburi and Phraya Tak (future King Taksin) to attack Maha Nawrahta at Siguk to the west of Ayutthaya. Swelled by the Siamese levies, Maha Nawrahta responded by sending two armies, with 20,000 men, 100 elephants and 500 horses each [30] (total of 40,000 men, surpassing their pre-invasion strength of 20,000–30,000 men), under Nemyo Gonnarat and Mingyi Zeyathu. The Burmese took position at the Chedi pagoda of Wat Phukhaothong temple, which was built by the Burmese king Bayinnaung after the First Fall of Ayutthaya in 1569 some two hundred years earlier, to the northwest of Ayutthaya, leading to the Battle of Wat Phukhaothong in January 1766. Siamese forces came out and attacked Burmese positions centered around the Chedi Phukhao Thong Pagoda. Phraya Phetchaburi and Phraya Tak implemented a new strategy. [30] Instead of directly charging onto all Burmese contingents at once, Siamese commanders chose to single out the Burmese west wing regiment of Mingyi Zeyathu at the west side of the pagoda to attack. The Siamese governor of Suphanburi, who had joined the Burmese ranks, volunteered to fight his own former Siamese comrades. Phraya Phetchaburi challenged the former governor of Suphanburi for a personal battle. The governor of Phetchaburi (fought for Siam) and the governor of Suphanburi (fought for Burma) engaged in an elephant duel. However, the defected governor of Suphanburi was eventually shot dead by a Siamese fire. [30]

Mingyi Zeyathu at the west wing faced intense Siamese attacks and was on the verge of being routed. Mingyi Zeyathu decided to fall back in order to feign retreat and maneuvered to the eastern side of the pagoda, successfully outflanking the Siamese in the rear. Nemyo Gonnarat, upon seeing Mingyi Zeyathu's movements, drove his army to join the commotion. The Siamese were attacked in both front and rear, split into two, encircled, routed and defeated. Phraya Phetchaburi and Phraya Tak retreated into the Ayutthaya citadel. The Burmese captured 2,000 Siamese men, 200 Siamese elephants and 200 Siamese guns. [30] The ensuing battle wiped out much of the several-thousand-strong Siamese army and the rest were taken prisoner. The remaining Siamese troops retreated into the city and shut the gates. [8] [57]

After the battle, Maha Nawrahta at Siguk praised the Siamese governor of Suphanburi who, despite being a Siamese, died in the war for Burma. [30] Maha Nawrahta pointed out that Mingyi Zeyathu had violated the martial law by cowering and retreating in the face of the enemies, making rash movements causing losses on Burmese side and, therefore, deserved death penalty. Nemyo Gonnarat and other Burmese commanders, however, defended Mingyi Zeyathu by saying that decisions of Mingyi Zeyathu was made out of desperate attempts to save the situation as his contingent was heavily attacked by the Siamese. Maha Nawrahta then said that Mingyi Zeyathu was still guilty by the law but he would pardon and spare Mingyi Zeyathu only by the pleas of his comrade commanders. [30]

Bang Rachan encampment

By February 1766, the Chiang Mai Burmese column under Nemyo Thihapate had swept all the way from the north to Ang Thong, taking position and battling in the northern outskirts of Ayutthaya. While Nemyo Thihapate was besieging Ayutthaya, a local resistance of Siamese villagers of Bang Rachan emerged in his rear. The Bang Rachan or Bang Rajan encampment village was the first and only successful movement against the Burmese invaders since the beginning of the war. Bang Rachan was led by non-elite commoners. It was one of very few commoner deeds that was recorded in Siamese royal chronicles. The story of Bang Rachan villagers was totally absent in Burmese chronicles, maybe due to the fact that Bang Rachan resistance, if ever existed, was a minor threat to the main Burmese army. Bang Rachan narrative was recounted many times in versions of Thai chronicles, earliest extant in 1795, written in patriotic tone. The story of Bang Rachan was expanded by nationalist historiography of early twentieth century [58] and continued to inspire Thai nationalism into modern times.

Inhabitants of fallen Siamese towns either fled into the forests or entered into service of Burmese military. Bang Rachan villagers fought with a local Burmese garrison in Wiset Chaichan rather than the main Burmese forces. A venerable monk Phra Acharn Thammachot from Suphanburi moved to reside in Wat Phokaoton temple in Bang Rachan, [59] attracting many followers. By February 1766, refugee Siamese people from many towns in the area including Wiset Chaichan, Singburi and Sankhaburi gathered in Bang Rachan around the monk Thammachot. [50] A group of Siamese men led by Nai Thaen were dissatisfied with Burmese treatment as they were extorted of money and family members, according to Thai chronicles. [50] Nai Thaen then led his group to kill a number of Burmese officials and fled to join the monk Thammachot at Bang Rachan, leading to the inception of Bang Rachan encampment in February/March 1766. By the time of Bang Rachan uprising, the Burmese main armies had already established themselves on the outskirts of Ayutthaya.

Nai Thaen was the leader of the Bang Rachan defenders, while the monk Thammachot served as the spiritual leader, enchanting magical amulets for Bang Rachan fighters. [50] Nai Thaen fortified his position in Bang Rachan and gathered 400 men for battle. Bang Rachan endured eight Burmese attacks in five months, [60] according to Thai tradition, from February to June 1766. The minor Burmese garrison at Wiset Chaichan sent first attack with 500 men, second attack with 700 men and third attack with 900 men, all of which were repelled by Bang Rachan. The fourth attack in March 1766 was remembered as a victorious battle for the Siamese. The Burmese forces of 1,000 men approached Bang Rachan. Nai Thaen, now had 600 men, led his compatriots to fight the Burmese at a canal in modern Sawaeng Ha, Ang Thong. The Burmese were again repelled and the Burmese commander was killed. However, Nai Thaen the Bang Rachan leader was incapacitated by a gunshot on his knee. The leadership was then taken over by another Siamese commoner man Nai Chan Nuad Kheo ('Chan the Moustached').

After initial success of Bang Rachan encampment, the Burmese were opted to send larger troops. The sixth wave of more than 1,000 Burmese men was led by a Sitke from Tavoy. Bang Rachan requested two cannons from Ayutthaya to step up the defense. However, King Ekkathat decided not to grant the cannons to Bang Rachan for fear that if Bang Rachan was to fall to the Burmese, the precious Ayutthayan cannons would fall into Burmese hands. [50] Phraya Rattanathibet the Minister of Palace Affairs went to Bang Rachan to help the defenders to cast their own cannons from bronze. The seventh attack from 1,000-men Burmese force was again repelled by Bang Rachan, under leadership of Nai Chan

The war between Bang Rachan and the Burmese took a turn in April/May 1766 when Thugyi, a Mon refugee in Siam, collaborated with Burma and volunteered to take down Bang Rachan. (When the Burmese forces left Siam after the fall of Ayutthaya, this Thugyi was left to be in charge of small Burmese garrison in Ayutthaya.) Thugyi improvised a new strategy by not facing the Siamese in open field but rather fortified himself in a stockade. Nai Chan led Bang Rachan fighters to attack Thugyi but failed to dislodge the Mon commander. Thugyi retaliated by attacking (the eighth and last time) and firing cannons into Bang Rachan, killing many Bang Rachan villagers, leading to the Battle of Bang Rachan in May. Phraya Rattanathibet managed to cast two cannons but they were broken and not functional. Nai Chan the leader of Bang Rachan was shot dead in battle. Rattanathibet then gave up and returned to Ayutthaya. Bang Rachan persisted until June 20 (2nd waning of eighth lunar month), [60] 1766 when Bang Rachan encampment finally fell to the Burmese after enduring eight Burmese attacks in five months. Bang Rachan villagers eventually dispersed and the resistance was put to end.

First Chinese invasion of Burma (December 1765 – April 1766)

Burmese and Chinese sphere of power had been overlapping in the Shan and Tai Nuea states at the Burmese–Chinese frontiers, where the trans-border trade between Yunnan and Burma had been flourishing. [61] With the declining powers of the Burmese Toungoo dynasty in early half of eighteenth century, Qing China exerted influence over those border Tai states including Mogaung and Bhamo in Irrawaddy valley, Hsenwi and Tai Lue Sipsongpanna. These Shan states served as the buffer between Burma and China and also paid tributes to one or both powers. [16] With the resurgence of Burma under Alaungpaya of the newly-founded Konbaung dynasty, however, Burma regained its control over the Shan states, leading to Sino–Burmese conflicts on the borders. In 1762, Burma conquered Gengma, Mengding and Hsenwi. In the same time, there was a civil war in Kengtung between two contenders for the throne – Sao Mong Hsam and his nephew Sao Pin.

In 1765, King Hsinbyushin sent Nemyo Thihapate to subjugate and pacify Lanna as a part of his plan to conquer Ayutthaya. Also in 1765, the combined Burmese–Kengtung forces attacked Sipsongpanna, [62] which had been under Chinese suzerainty. Previously, the Qing had pursued a non-interventionist policy by letting the allied native Tai chiefs to ward off Burmese invasions by themselves. [62] However, in 1765, Liu Zhao (劉藻) the Viceroy of Yungui tried an alternative policy by deploying the main Qing Green Banner Army to fend off Burmese attacks, considering the native Tai forces ineffective against the Burmese. As Sino–Burmese tension escalated, the Burmese court shut down the Shan borders, hampering the Yunnanese traders from conducting their usual businesses. [61] The Yunnanese–Chinese merchants forced their way through the Burmese border barricade, resulting in two incidents, in which a Chinese merchant was imprisoned in Bhamo and another killed in Kengtung. [19] Provoked, Chinese authorities in Yunnan then used these minor incidents as the pretext for military punishment.

After Nemyo Thihapate had left Lanna to invade Ayutthaya in mid-1765, Liu Zhao sent 3,500 men [62] from the Green Standard Army to attack Kengtung in December 1765, [36] leading to the first Chinese invasion of Burma. However, the Chinese invaders were readily repelled by the Burmese commander Nemyo Sithu in Kengtung. The Qianlong Emperor, upon hearing about the Chinese defeat in Kengtung, sacked Liu Zhao from his position and appointed Yang Yingju (楊應琚) as the new viceroy of Yungui instead. Liu Zhao then committed suicide out of guilt and shame. Though battle-hardened Burmese forces eventually drove back the besiegers, Burma was now fighting on two fronts, one of which had the largest army in the world. [63] Nonetheless, Hsinbyushin apparently (as it turned out, mistakenly) believed that the border conflict could be contained as a low-grade war. He refused to recall his armies in Siam though he did reinforce Burmese garrisons along the Chinese border—in Kengtung, Kenghung and Kaungton.[ citation needed]

Siamese Preparations

Siamese defensive strategy

Ayutthaya had repaired and revitalized its unused defense system since Alaungpaya's invasion in 1760. However, the manpower control inefficiency continued to haunt Siamese defense capabilities. [27] Effective manpower mobilization and strong military leadership was not present as they were in the sixteenth century. Peripheral governors had been deprived of their military prowess for they were prone to rebellions. [24] King Ekkathat had sent Siamese forces to halt the Burmese advances at the frontiers but they were all defeated and failed. Siamese commanders were inexperienced and lacked strategies against the tactics of the Burmese. Ayutthaya exerted futile and minimal attempts to hold peripheral cities as the Burmese invaded. Ayutthayan court recruited forces from the peripheral cities, including their governors, to defend Ayutthaya city. This left the periphery even less defended as outlying Siamese towns quickly fell to Burmese conquests. With the Burmese victories at Paknam Prasop and Wat Phukhaothong in January 1766, they were able to set foot on Ayutthayan outskirts to lay siege on the Siamese royal city. Suffering from defeats, Ayutthaya had no choice but to resort to traditional defensive strategy. Siam evacuated all people from the suburbs into the city, shut the city gates tight and put up defenses.

Siamese defense strategy relied on supposed impregnability of Ayutthaya's city walls and the arrival of Siamese wet season. Traditional warfare between Burma and Siam were usually conducted in dry season between January and August. The rains arrived in May and the waters began to rise in September, reaching the peak in November. In the flooding season, outlying areas of Ayutthaya became inundated and turned into a vast sea of flood water. Any invaders were obliged to leave Ayutthaya at the advent of flooding season as high water level would cripple the warfare. Military personnel would find less comfort in floods and provisions would be damaged. King Ekkathat and his court contemplated that the Burmese would eventually retreat at the end of dry season. [64] However, the Burmese had other plans and did not intend to leave. King Hsinbyushin planned his campaign to conquer Siam to possibly span many years, not to be deterred by the rainy season. Siam would simply wait for the Burmese to run out of their endurance and, with the coming of the treacherous rainy season, became exhausted, eventually abandoning their campaign. The Siamese command had made careful preparations to defend the capital. The fortifications consisted of a high brick wall with a broad wet ditch. The walls were mounted with numerous guns and cannon that they had stockpiled since the last Burmese war. Finally, they had banked on the advent of the rainy season, which had more than once saved the city in the past. They believed that if they could only hold out until the onset of the monsoon rains and the flooding of the great Central Plain, the Burmese would be forced to retreat. [5] [57]

When the Burmese approached Ayutthaya in January 1766, King Ekkathat moved all of Buddhist monks in temples of Ayutthayan outskirts, including his brother Uthumphon the temple king, to take refuge inside of Ayutthaya city walls. Uthumphon moved from Wat Pradu Songtham temple to reside at Wat Ratcha Praditsathan temple adjacent to the northern wall inside of Ayutthaya citadel. Uthumphon had previously left monkhood to command the war during Alaungpaya's invasion of 1760 but he faced political repercussion from Ekkathat. This time, Uthumphon was again asked to do the same thing by some Siamese nobles but the temple king sternly refused. Whenever he went out from his temple to ask for alms, Uthumphon received many letters pleading him to save the kingdom but Uthumphon was persistent on his stay in monkhood.

Ayutthaya City Walls and Armory

The Ayutthaya city situated on an island at the confluence of three rivers – namely Chao Phraya, Lopburi and Pasak, surrounded by the waters serving as natural city moat. During the period of Burmese–Siamese wars of the sixteenth century, Ayutthaya city walls were rebuilt from brick and stones and expanded to fully reach riverbanks of all sides. During the long period of external peace, the Ayutthayan walls stood for two centuries with limited usage. The walls were renovated several times. The most important occasion was during the reign of King Narai when Western engineers contributed to more sturdy, reinforced style of the wall. [65] After 1586, no invaders had reached the Ayutthaya city for nearly two hundred years [22] until 1760. The Ayutthaya city walls stood three wa and two sok (seven meters) in height with two wa (about four meters) in thickness. It has up to sixty regular city gates with about twenty large tunnel gates that allowed large group of people or domesticated animals to pass. It also has water gates that facilitate riparian transports.

Siam had learned production of matchlock firearms and bronze cannons from the Portuguese in the sixteenth century. Siam had domestic furnaces for cannon casting and became a renowned manufacturer of cannons. However, both Burma and Siam were unable to produce their own flintlock muskets, which were to be exclusively imported from the Europeans. Siamese government purchased a large number of Western-produced, cast-iron, larger-caliber cannons. Some of the cannon were thirty feet (9.1 m) long, and fired 100 lb (45 kg) balls. [66] Individual cannons were religiously worshipped by the Siamese for they believed supernatural protector spirits resided in those cannons. [67] Siam also utilized small-caliber breechloader cannons that were employed in hundreds into battlefields and could also be mounted onto elephants or ships.

Even though Ayutthaya possessed a large number of firearms, during the Burmese invasion of 1765–1767, they were not utilized to full potential. Long hiatus from warfare meant few Siamese were skilled to effectively operate those firearms. It is shown in Thai chronicles narrative that Siamese cannoneers mishandled their own cannons and missed their targets. When the Burmese finally captured Ayutthaya in 1767, they found over 10,000 new muskets and ammunition in the royal armory, still unused even after a 14-month siege. [68] Meanwhile, the Burmese put emphasis on marksmanship training to inflict greatest damage on their enemies. In 1759, King Alaungpaya issued a royal decree instructing his musketeers on how to properly use the flintlock firearms. [36] It is estimated that sixty percent of Burmese military personnel operated flintlock muskets. [69]

Siege of Ayutthaya (January 1766 – April 1767)

Early siege

In February 1766, the Burmese invading armies laid siege on Ayutthaya with two Bogyoke or grand commanders Maha Nawrahta and Nemyo Thihapate encamping in the west and the north of Ayutthaya, respectively;

- Maha Nawrahta, with his Burmese Tavoy column of more than 20,000 men and his subordinate commanders including Nemyo Gonnarat, Mingyi Zeyathu and Mingyi Kamani Sanda, stationed at Siguk about ten kilometers to the west of Ayutthaya.

- Nemyo Thihapate, with his Burmese Lanna column of more than 20,000 men, headquartered at Paknam Prasop about seven kilometers to the north of Ayutthaya.

Realizing that they had less than four months before the rainy season, the Burmese command initially launched a few assaults on the city walls. But the place proved too strong and too well-defended. Because of the numerous stockades outside the city, the Burmese could not even get near the wall, and those that got near were cut down by musket fire from atop. The Burmese now drew a line of entrenchments round the city, and prepared to reduce it by famine. The Siamese inside of Ayutthaya, however, flared quite well during the initial stage of the siege. Food supply was plentiful inside of the city as French missionary noted that "the beggars alone suffered from hunger and some died of it". Life went on as usual in the Ayutthaya citadel. Burmese blockade of Ayutthaya was relatively less-manned on the eastern side as it would later be shown that Ayutthaya was still able to communicate with outside through eastern perimeters. This Burmese–Siamese war then became a battle of endurance. No major battles occurred in Ayutthaya for seven months between February and September 1766.

Eastern Front: Battle of Paknam Yothaka

By 1766, Western and Northern Siam had fallen under Burmese occupation but Eastern Siam remained untouched. Since mid-1765, Prince Kromma Muen Thepphiphit, Ekkathat's rebellious half-brother, had been put under political confinement in Chanthaburi on Siamese eastern coast by orders of King Ekkathat. There, Prince Thepphiphit attracted a large number of Eastern Siamese followers. In mid-1766, upon learning about developments in Ayutthaya, Thepphiphit decided to gather his men from Chanthaburi and move to Prachinburi, establishing himself. Already a prominent political figure, Prince Thepphiphit became a new rallying point for anti-Burmese movement in Siam. Eastern Siamese men from Prachinburi, Nakhon Nayok, Chonburi, Bang Lamung and Chachoengsao rallied to Prince Thepphiphit at Prachinburi. Prince Thepphiphit built himself a stockade at Paknam Yothaka, about 30 kilometers to the southwest of Prachinburi at the confluence of Bangpakong and Nakhon Nayok rivers in modern Ban Sang, Prachinburi, to muster an army to attack the besieging Burmese at Ayutthaya. Thepphiphit's place at Prachinburi accommodated ten thousands of Siamese war refugees. [50] The Siamese prince raised a vanguard army of 2,000 men, preparing to march to Ayutthaya and declaring to save the Siamese royal city. [28]

When the news Prince Thepphiphit's uprising reached Ayutthaya, a large number of Siamese nobles and their subordinates left Ayutthaya to join with Thepphiphit at Prachinburi to the east, including Phraya Rattanathibet the Minister of Palace Affairs and many-time commander. Motivation of Prince Thepphiphit in his uprising probably stemmed from both patriotic and political intentions. King Ekkathat, who would never trust Thepphiphit, sent several forces to subjugate his restive half-brother. Maha Nawrahta and Nemyo Thihapate also sent Burmese forces to the east to put down Thepphiphit. The Burmese forces attacked Prince Thepphiphit at Paknam Yothaka, leading to the Battle of Paknam Yothaka in September 1766. Eastern Siamese regiment of Prince Thepphiphit was annihilated by the Burmese, with Thepphiphit fleeing to the northeast. Eastern Siamese resistance to Burmese invaders eventually dispersed. The Burmese then settled in Prachinburi and at Paknam Cholo in modern Bang Khla, Chachoengsao on Bangpakong River, leading to Burmese presence in Eastern Siam (these Burmese contingents would later engage in battle with Phraya Tak four months later in January 1767.).