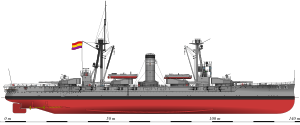

Illustration of España in 1912

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name | España class |

| Builders | Sociedad Española de Construcción Naval, Ferrol, Spain |

| Operators |

|

| Preceded by | None |

| Succeeded by | Reina Victoria Eugenia class (planned) |

| Built | 1909–1921 |

| In commission | 1913–1937 |

| Completed | 3 |

| Lost | 3 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 140 m (459 ft 4 in) o/a |

| Beam | 24 m (78 ft 9 in) |

| Draft | 7.8 m (25 ft 7 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 19.5 knots (36.1 km/h; 22.4 mph) |

| Range | 5,000 nmi (9,300 km) at 10 knots (19 km/h) |

| Complement | 854 |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

The España class was a series of three dreadnought battleships that were built for the Spanish Navy between 1909 and 1921: España, Alfonso XIII, and Jaime I. The ships were ordered as part of an informal mutual defense agreement with Britain and France, and were built with British support. The construction of the ships, particularly the third vessel, was significantly delayed by shortages of materiel supplied by the UK during World War I, particularly armaments; Jaime I was almost complete in May 1915 but her guns were not delivered until 1919. The ships were the only dreadnoughts completed by Spain and were the smallest of the type built by any country. The class's limited displacement was necessitated by the constraints imposed by the weak Spanish economy and existing naval infrastructure, requiring compromises on armor and speed to incorporate a main battery of eight 12-inch (305 mm) guns.

España represented Spain during the opening of the Panama Canal in 1915 and conducted training exercises with Alfonso XIII after she entered service later that year. Both ships conducted long-range voyages to North and South America in 1920–1921; España was damaged in an accidental grounding off the coast of Chile. Both vessels provided gunfire support to ground forces engaged in the Rif War, which started in mid-1921, and Jaime I joined them there after her commissioning later that year. In 1923, España ran hard aground off Cape Tres Forcas while bombarding Rif positions and could not be freed before storm damage destroyed the ship in November 1924. Some of her guns were salvaged and later used as coastal artillery in Spain. The two surviving ships of the class supported the landing at Alhucemas, where Alfonso XIII served as the flagship.

After King Alfonso XIII was deposed and the Second Spanish Republic was proclaimed in 1931, Alfonso XIII was renamed España and both members of the class were reduced to reserve to reduce costs. Jaime I returned to service for use as the fleet flagship in 1933. Plans to modernize the ships in the mid-1930s were interrupted by the start of the Spanish Civil War. España was seized by the rebel Nationalist faction at the start of the conflict while the Republican government retained control over Jaime I. España was used to enforce a blockade of Republican-controlled ports in northern Spain; the Spanish Republican Navy briefly deployed Jaime I to break the blockade but neither side attacked the other. España was lost after striking a mine in April 1937, though almost her entire crew was saved. Jaime I was attacked by German and Italian bombers during the war before being destroyed by an accidental explosion in June 1937. Guns from Jaime I were recovered and used for coastal batteries.

Background

The Spanish public blamed the Navy for the country's disastrous losses in the Spanish–American War of 1898 but recognized the need to modernize and rebuild it. The first attempt to rebuild the Navy came in the Fleet Plan of 1903, which called for a fleet centered on seven 15,000-metric-ton (14,763-long-ton) battleships and three 10,000-metric-ton (9,842-long-ton) cruisers. This plan proved to be too ambitious for the weak Spanish economy and an unstable Spanish parliament was unable to provide funding. The Fleet Plan of 1905 proposed a fleet of eight 14,000 t (13,779-long-ton) battleships, a number of torpedo boats, and submarines; this plan also fell victim to the weaknesses of the Spanish government and a lack of public support. International developments, particularly conflicts with Germany in the First Moroccan Crisis, provided the impetus and public support necessary for the Spanish government to embark on a major naval construction program. [1]

In April 1904, Britain and France reached the Entente Cordiale, putting aside their traditional rivalry to oppose German expansionism. The agreement directly affected Spain because it settled matters of control over Morocco and placed Tangier under joint British–French–Spanish control. The agreement brought Spain closer with Britain and France, leading to an exchange of notes between the three governments in May 1907, by which time a strong cabinet led by Antonio Maura had come to power. The notes created an informal agreement to contain the German-led Central Powers; Britain would concentrate the bulk of the Royal Navy in the North Sea while Spain would contribute its fleet to support the French Navy against the combined fleets of Italy and Austria-Hungary. Britain and France would provide technical assistance to develop new warships for the Spanish fleet. Accordingly, Maura secured passage of the Fleet Plan of 1907, which proposed the construction of three battleships, several destroyers, torpedo boats, and other craft. The construction plan was to last for eight years. Debates over the plan took place in the Cortes Generales (General Courts—the Spanish legislature) until the end of November and a final approval vote on 2 December. The 1907 Fleet Plan was formally signed into law on 7 January 1908. [1] [2]

Development

Work on the new design had begun before the fleet plan was approved by the legislature. Initial plans called for the three ships to displace 12,000 t (11,810 long tons) and have an armament of four 12-inch (305 mm) and at least twelve 6-inch (152 mm) guns in a manner similar to standard British pre-dreadnoughts of the period. The commissioning of the revolutionary "all-big-gun" Dreadnought in late 1906 prompted Commodore José Ferrándiz y Niño, the Spanish naval minister, to press the Junta Técnica de la Armada (Navy Technical Board) to revise its design to match the new, more powerful type of battleship in March 1907. Some consideration was given to reducing the caliber of the main battery to 11- or 9.2-inch (279 or 234 mm) guns, but six of the nine board members agreed that the 12-inch gun should be retained. With the general type of ship determined, the Navy began discussions over general design requirements, given the limitations that would be imposed on the new ships. [3]

The Spanish Navy was principally concerned with defending its main naval bases at Ferrol, Cádiz, and Cartagena; given this requirement, the ships would not need an extensive cruising range. The need to keep the new battleship design tightly constrained due to the frail Spanish economy and industrial sector was of secondary importance. [4] [5] A third constraint was the need to build ships small enough to fit in existing dockyard facilities because Spain had insufficient funds to both build larger battleships and to enlarge the navy's dockyards. [6] As a result, the design requirements called for relatively heavy offensive power with minimal range and armor protection. The Navy began discussing the design requirements with Armstrong Whitworth and Vickers in 1907. On 5 September 1907, Vickers provided a proposed design for a 15,000-ton battleship armed with eight 12-inch guns. This design was the basis for the requirements for the design competition, which was issued on 21 April 1908. [4] Rather than simply order the ships from foreign builders, the government required any tender to include provisions for the submitter to take control of and modernize the Spanish shipyard facilities that would build the vessels. While this would increase costs and delay completion of the ships, the government decided improving domestic facilities was an important goal of the program. [3]

Four shipbuilders submitted bids: the Italian Gio. Ansaldo & C. led a group that included the Austro-Hungarian Škoda Works and the French Marrel Freres Forges de La Loire et du Midi; the French firm Schneider-Creusot partnered with Société Nouvelle des Forges et Chantiers de la Méditerranée and Forges et Chantiers de la Gironde; the Spanish firm Sociedad Española de Construcción Naval (SECN), which was formed by Vickers, Armstrong Whitworth, and John Brown & Company; and a group of Spanish industrialists backed by Palmers Shipbuilding and Iron Company and William Beardmore and Company. Only the first three proposals were seriously considered; the fourth was considered to be too vague. The Junta Superior de la Armada (the Navy Staff) and the Navy Minister were responsible for reviewing the three proposals. Ansaldo prepared two design variants; the first called for four twin gun turrets for the main battery with one forward, one aft, and two offset amidships. The second proposal had two triple turrets fore and aft with a twin turret on the centerline amidships. Artillery experts in the Navy rejected the second variant. The SECN and Schneider designs featured the same arrangement as the first Ansaldo proposal. [7]

In October 1908, the Artillery Committee met to make its recommendations to the Junta Superior. The Committee concluded the SECN and Schneider proposals were superior to the Ansaldo version but neither had a marked advantage over the other. The following month, the Naval Construction Committee met to evaluate the proposals. It recommended the SECN design followed by Schneider and with Ansaldo last. The Office of the Navy Controller also evaluated the proposals in November and advised the Junta Superior only the SECN bid met the design requirements without any legal, administrative, or cost problems. [8] Given the strategic context that foresaw the likely use of the ships against the Italian and Austro-Hungarian fleets, the Ansaldo-led consortium had obvious drawbacks. [9] In February 1909, the Navy requested a revised design from SECN to incorporate several alterations including an increased freeboard to improve seakeeping, an increased height and length of the main belt armor, and the addition of individual rangefinders for each gun turret. SECN agreed to make the changes on 20 March and the company received the contract on 14 April. [10]

Due to the constraints imposed by the Spanish economy, the resulting design produced the smallest dreadnought-type battleships ever built. [6] They were obsolete before completion due to rapid technological change—most significantly the advent of the superdreadnought battleships—and lengthy delays in completion of the later units of the class. [11]

Design

General characteristics

The España-class ships were 132.6 m (435 ft) long at the waterline and 140 m (459 ft 4 in) long overall. They had a beam of 24 m (78 ft 9 in) and a draft of 7.8 m (25 ft 7 in); their freeboard was 4.6 m (15 ft) amidships, much lower than was normal for battleships of the period. They displaced 15,700 metric tons (15,500 long tons) as designed and up to 16,450 t (16,190 long tons) at combat load. The vessels had two tripod masts and a small superstructure. [6] They were equipped with six 75 cm (30 in) searchlights. [12] The ships were reasonably stable compared to foreign designs but they had a low metacentric height of 1.56 m (5 ft 1 in) at full loading that caused them to have poor stability when damaged. [13] Steering was controlled with a single semi-balanced rudder. At full speed, the ships could make a 180 degree turn in the space of 321 m (1,053 ft). [14]

Each ship had a crew of 854 officers and enlisted men, [6] though in peacetime the crew was limited to around 700 for habitability reasons. The enlisted crew spaces were located forward in the upper deck and were cramped and unhygienic; they were split between two areas, the first being a large mess deck between the barbettes for the forward turret and the starboard wing turret. The rest of the enlisted men were housed in the forward casemates for the secondary guns. The cabins for non-commissioned officers were also located in the casemates. The superstructure included several cabins for senior officers. [15] [16] The ships were initially painted black but in the 1920s they were repainted gray. Alfonso XIII's funnel bore a white identification band and Jaime I's bore two; these bands were removed from both ships after the start of the Civil War. Jaime I was also repainted dark gray at this time. [17]

Machinery

The ships' propulsion system consisted of four-shaft Parsons steam turbines and steam was provided by twelve coal-fired water-tube Yarrow boilers. [6] The turbines drove three-bladed screw propellers that had diameters of 2.4 metres (7 feet 10 inches). Two spare screws were kept aboard each ship. [18] The boilers were trunked into a single funnel that was placed amidships; the funnel's location far from the foremast kept the latter's spotting top free from smoke interference but still rendered the spotting top on the mainmast essentially useless. [19]

The engines were rated at 15,500 shaft horsepower (11,600 kW) and produced a top speed of 19.5 knots (36.1 km/h; 22.4 mph). [6] According to the design contract, the engines were to be capable of a normal maximum of 22,000 shp (16,000 kW) with a top speed of 19.9 knots (36.9 km/h; 22.9 mph), and up to 26,000 shp (19,000 kW) and 20.2 knots (37.4 km/h; 23.2 mph) at forced draft. All three ships exceeded 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph) in speed trials. [18] Each ship could store up to 1,900 t (1,870 long tons) of coal; according to Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, this permitted a cruising radius of 5,000 nautical miles (9,300 km; 5,800 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph), [6] though the historian Agustín Rodríguez González states the ships had a range of 7,500 nmi (13,900 km; 8,600 mi) at a speed of 10.8 knots (20.0 km/h; 12.4 mph). [14]

Armament

The ship's main armament consisted of eight Vickers Mk H. 12-inch 50- caliber guns. These guns were housed in four twin-gun turrets, arranged with two on the centerline fore and aft, the others en echelon as wing turrets. [20] Each weighed 65.6 metric tons (64.6 long tons) and fired an 850-pound (385 kg) shell at a muzzle velocity of 3,000 ft/s (914 m/s). The guns had a maximum range of 23,500 yards (21,500 m) and a rate of fire of one round per minute. [21] The turrets were hydraulically operated and could be loaded at any angle of elevation. The en echelon arrangement was chosen over superfiring turrets such as those used in the American dreadnoughts to save weight and cost. All four turrets could in theory fire on the broadside and three of them could fire ahead or astern. [5] [6] Blast effects from the wing turrets, however, generally prohibited firing them across the deck or directly ahead and astern. [19]

The secondary battery comprised twenty 4-inch (102 mm), 50-caliber guns mounted individually in casemates along the length of the hull. They were manufactured by several Spanish arsenals [20] and fired a 31-pound (14 kg) shell. [22] The guns were too close to the waterline, however; they were unusable in heavy seas and had a limited range caused by insufficient elevation. The guns were also too weak to be effective against contemporary destroyers, which were becoming increasingly powerful. [19] The ships also carried four 3-pounder guns, two machine guns, and two landing guns that could be taken ashore. [5] [6]

Armor

The armor layout for the España class was essentially a scaled-down version of that used in the British Bellerophon class. [12] The reductions were mostly due to the heavy armament in a vessel of such limited displacement. [23] The main belt armor was 8 in (203 mm) thick and tapered to 4 in (102 mm) on either end of the central citadel. The upper belt that protected the casemate guns was 6 in (152 mm) thick. Each turret, which had 8 in sides, sat on a barbette that was protected with 10 in (254 mm) thick plating. The conning tower also had 10-inch thick sides. Both the armored deck and the torpedo bulkhead were 1.5 in (38 mm) thick. [6] The ships' heavy armor plating consisted of Krupp cemented steel, with Krupp homogeneous steel used for armor thinner than 4 in (100 mm); both types were manufactured in Britain. [24]

Though the ships were poorly armored compared to most foreign designs, the ships' underwater protection was the greatest weakness in the armor scheme. The torpedo bulkhead was placed too close to the outer hull, which reduced its ability to absorb damage. This weakness played a central role in the losses of both España to grounding in 1923 and the sinking of Alfonso XIII by a single mine in 1937. [24]

Modifications

Only limited modifications were possible due to technical constraints imposed by the need to keep displacement low and insufficient funds to effect a major reconstruction to free up tonnage for other uses. [25] The arrangement of the main battery occupied much of the deck space, limiting what could be done to update the vessels. [20] The Navy considered proposals to modernize the three battleships in the early 1920s but the Spanish military budget was being consumed by the costs of the Rif War in North Africa so the proposed modernization was not carried out. These modernization plans called for the installation of new fire control equipment with more effective rangefinders, additional, newer anti-aircraft guns, and the building of anti-torpedo bulges into the hull to improve underwater protection for a loss of one knot of speed. Deck armor was also to be strengthened. [26] Only minor modifications were possible. In 1926, both Jaime I and Alfonso XIII had a pair of Vickers 76.2-millimeter (3 in) anti-aircraft guns installed, one each on top of turret numbers 1 and 2. In the 1930s, the foremast was reduced slightly on the two surviving ships. [17]

A more ambitious plan to significantly improve the surviving ships' capabilities was proposed in the mid-1930s. The height of the wing turret barbettes was to be increased, improving their fields of fire and freeing up space around the turrets for a new secondary battery of 120 mm (4.7 in) Mk F dual-purpose guns. The ships were to carry twelve of the guns individually in open mounts; the casemates of the old secondary guns would be converted into more crew spaces. A new anti-aircraft battery of either ten 25 mm (1 in) or eight 40 mm (1.6 in) guns were to be fitted, the type would be determined by tests of their effectiveness. Other changes were to be made to improve fire-control systems, overhaul the machinery, and install anti-torpedo bulges, among other improvements but the start of the Spanish Civil War in July 1936 prevented work on either ship from beginning. [27]

After the Nationalists seized her in 1936, Alfonso XIII—since renamed España—had her 76.2 mm (3 in) guns removed for use ashore. They were replaced with four German 88 mm (3.5 in) SK C/30 flak guns and two 20 mm (0.79 in) C/30 anti-aircraft guns. Jaime I, which remained with the Republicans, was reequipped with two Vickers 47 mm (1.9 in) 50-caliber anti-aircraft guns and a twin 25 mm (0.98 in) Hotchkiss mounting. [28]

Construction

A new 184 by 35 m (604 by 115 ft) drydock and two 180 by 35 m (591 by 115 ft) slipways were built at Ferrol to accommodate the construction of the three battleships. All material except the armor plate, heavy guns, and fire control equipment was manufactured in Spain. The contract specified a build time of four years for the first ship, five years for the second, and seven years for the third. [29] Despite the allowance for longer construction times for the later units, their completion, particularly that of the third unit, Jaime I, was delayed by a lack of materials from Britain as a result of the outbreak of World War I in July 1914. [5] The main guns for Jaime I were not delivered until 1919; she had been completed apart from her armament in May 1915. [29] [30]

| Name | Builder [6] | Laid down [6] | Launched [6] | Completed [6] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| España | SECN, Ferrol | 6 December 1909 | 5 February 1912 | 23 October 1913 |

| Alfonso XIII | 23 February 1910 | 7 May 1913 | 16 August 1915 | |

| Jaime I | 5 February 1912 | 21 September 1914 | 20 December 1921 |

History

Early careers

España was the only member of the class that was completed by the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, though she did not see action because Spain remained neutral for the duration of the war. [31] In August 1914, she participated in the opening ceremonies for the Panama Canal. [32] Alfonso XIII joined her in August 1915 in the 1st Squadron of the Spanish fleet. During the war, the fleet conducted training operations in home waters. Alfonso XIII was involved in assisting ships in distress and suppressing civil unrest during and immediately after the war. In late 1921, Jaime I was completed. Throughout the early 1920s, the three ships served in the Training Squadron. España and Alfonso XIII were sent on long-distance cruises to North and South America in 1920 and 1921, respectively. [31] [33] [34] During España's voyage, she was damaged off the coast of Chile and required extensive repairs before she could return home. [35] [36]

During this period, the Riffians living in Spanish Morocco rebelled against the Spanish colonial government, initiating the Rif War in mid-1921. All three España-class battleship saw action during the conflict, primarily providing artillery support to Spanish ground forces engaging the Rif rebels. In August 1923, while bombarding Rif positions, España ran aground off Cape Tres Forcas. A lengthy salvage operation failed to free the ship, and, in November 1924, severe storms battered the wreck and broke the hull in half, rendering her a complete loss. Alfonso XIII served as the flagship of the Spanish fleet during the landing at Alhucemas in 1925. Spanish forces were able to defeat the rebels by 1927. [37] [38]

In 1931, after the overthrow of King Alfonso XIII and the establishment of the Second Spanish Republic, his namesake battleship was renamed España to erase traces of the monarchy. [6] Both vessels were immediately decommissioned to reduce costs during the Great Depression, though Jaime I was recommissioned in 1933 to serve as the fleet flagship. [39] In the mid-1930s, the Spanish Navy considered modernization programs for the two surviving battleships but none came to fruition, mainly because of the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in July 1936. [40] España was undergoing a limited refit to bring her back into service in anticipation of the modernization when the Spanish coup of July 1936 initiated the conflict. [41]

Spanish Civil War

In 1936 at the start of the Nationalist uprising led by General Francisco Franco, the bulk of the Spanish Navy's fleet remained loyal to the Republican government. When most of the ship's officers declared support for Franco, España's crew killed most of them, but, after a duel with Nationalist coastal artillery batteries, they were persuaded to surrender and turn the ship over to Nationalist control. Jaime I remained under Republican control, serving as the core of the Spanish Republican Navy. The Republican fleet attempted to block the crossing of Franco's Army of Africa from Morocco to mainland Spain, resulting in a brief action between Jaime I and the gunboat Eduardo Dato, but German interference secured the Nationalists' passage. [42] [43] In August of that year, Jaime I was attacked and slightly damaged by two German bombers from the Condor Legion. [44] [45]

After being returned to service, España was used for coastal bombardment and to enforce the blockade of Republican ports in northern Spain, including Gijón, Santander, and Bilbao, frequently seizing vessels carrying supplies to the Republicans. Jaime I shelled Nationalist positions in Spanish Morocco and in September 1936 sortied with a pair of cruisers and four destroyers to disrupt the blockade imposed by España. Neither ship engaged the other and the Republicans withdrew in October that year, having achieved nothing. [46] [47] After returning to Spain's Mediterranean coast, Jaime I ran aground, necessitating repairs at Cartagena. While there in May 1937, she was attacked by five Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 bombers of the Italian Aviazione Legionaria. Reports of the damage inflicted are mixed; according to Albert Nofi the ship sustained minor damage but Marco Mattioli wrote the damage was more serious. [44] [48]

España was lost on 30 April 1937 off the coast of Santander while on blockade duty, having struck a single mine that had been laid by a Nationalist minelayer. She remained afloat long enough for the destroyer Velasco to take off most of her crew and only four men died in the sinking. [49] [50] Jaime I was still under repair at Cartagena in June when an accidental fire caused an internal explosion that destroyed the ship. [51] The Republicans raised the ship but determined she was beyond economical repair and discarded her on 3 July 1939. [6]

Many of the guns from the first España were recovered and used in coastal fortifications, some of which remained in service until 1999. Six of Jaime I's 12-inch guns were also salvaged and similarly employed after she was broken up in the 1940s. Jaime I's guns also remained in service until they were decommissioned in the mid-1990s. The second España (formerly Alfonso XIII) was never raised and her wreck was discovered in the early 1980s. Several expeditions to survey the wreck took place between February and May 1984. [52]

Notes

- ^ a b Fernández, Mitiukov, & Crawford, pp. 63, 65.

- ^ Rodríguez González, pp. 268–271.

- ^ a b Rodríguez González, p. 272.

- ^ a b Fernández, Mitiukov, & Crawford, pp. 66–67.

- ^ a b c d Fitzsimons, p. 856.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Sturton, p. 378.

- ^ Fernández, Mitiukov, & Crawford, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Fernández, Mitiukov, & Crawford, pp. 68–70.

- ^ Rodríguez González, p. 273.

- ^ Fernández, Mitiukov, & Crawford, p. 72.

- ^ Fitzsimons, p. 857.

- ^ a b Fernández, Mitiukov, & Crawford, p. 95.

- ^ Fernández, Mitiukov, & Crawford, p. 77.

- ^ a b Rodríguez González, p. 276.

- ^ Fernández, Mitiukov, & Crawford, p. 102.

- ^ Rodríguez González, p. 279.

- ^ a b Fernández, Mitiukov, & Crawford, p. 104.

- ^ a b Fernández, Mitiukov, & Crawford, p. 101.

- ^ a b c Fernández, Mitiukov, & Crawford, p. 84.

- ^ a b c Rodríguez González, p. 275.

- ^ Friedman, p. 65.

- ^ Friedman, p. 107.

- ^ Garzke & Dulin, p. 437.

- ^ a b Fernández, Mitiukov, & Crawford, p. 96.

- ^ Fernández, Mitiukov, & Crawford, p. 76.

- ^ Fernández, Mitiukov, & Crawford, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Rodríguez González, pp. 285–286.

- ^ Fernández, Mitiukov, & Crawford, pp. 91–93.

- ^ a b Fernández, Mitiukov, & Crawford, p. 73.

- ^ Hall, p. 504.

- ^ a b Sturton, p. 376.

- ^ Shepherd, p. 28.

- ^ Garzke & Dulin, p. 438.

- ^ Rodríguez González, p. 283.

- ^ Fernández, Mitiukov, & Crawford, p. 105.

- ^ Repairs to the Spanish Battleship "Espana", p. 569.

- ^ Rodríguez González, p. 284.

- ^ Fernández, Mitiukov, & Crawford, p. 106.

- ^ Rodríguez González, pp. 283–285.

- ^ Garzke & Dulin, pp. 438–439.

- ^ Rodríguez González, p. 286.

- ^ Beevor, pp. 71–73.

- ^ Rodríguez González, p. 287.

- ^ a b Nofi, p. 32.

- ^ Proctor, p. 28.

- ^ Fernández, Mitiukov, & Crawford, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Rodríguez González, pp. 287–288.

- ^ Mattioli, p. 11.

- ^ Rodríguez González, pp. 288–289.

- ^ Roskill, p. 381.

- ^ Gibbons, p. 195.

- ^ Fernández, Mitiukov, & Crawford, pp. 106, 108–109.

References

- Beevor, Antony (2006). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939. New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-297-84832-5.

- Fernández, Rafael; Mitiukov, Nicholas; Crawford, Kent (March 2007). "The Spanish Dreadnoughts of the España class". Warship International. 44 (1). Toledo: International Naval Research Organization: 63–117. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Fitzsimons, Bernard (1978). "España". The Illustrated Encyclopedia of 20th Century Weapons and Warfare. Vol. 8. Milwaukee: Columbia House. pp. 856–857. ISBN 978-0-8393-6175-6.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Garzke, William; Dulin, Robert (1985). Battleships: Axis and Neutral Battleships in World War II. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-101-0.

- Gibbons, Tony (1983). The Complete Encyclopedia of Battleships and Battlecruisers: A Technical Directory of All the World's Capital Ships From 1860 to the Present Day. London: Salamander Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0-86101-142-1.

- Hall, R. A. (1922). Robinson, F. M. (ed.). "Professional Notes". United States Naval Institute Proceedings. 48 (1). Annapolis: Naval Institute Press: 455–506. OCLC 682045948.

- Mattioli, Marco (2014). Savoia-Marchetti S.79 Sparviero Torpedo-Bomber Units. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-78200-809-5.

- Nofi, Albert A. (2010). To Train The Fleet For War: The U.S. Navy Fleet Problems, 1923–1940. Washington, DC: Naval War College Press. ISBN 978-1-88-473387-1.

- Proctor, Raymond L. (1983). Hitler's Luftwaffe in the Spanish Civil War. London: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-22246-7.

- "Repairs to the Spanish Battleship 'Espana'". The Panama Canal Record. XIV (37). Balboa Heights, C.Z.: The Panama Canal Press. 27 April 1921. OCLC 564636647.

- Rodríguez González, Agustín Ramón (2018). "The Battleship Alfonso XIII (1913)". In Taylor, Bruce (ed.). The World of the Battleship: The Lives and Careers of Twenty-One Capital Ships of the World's Navies, 1880–1990. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. pp. 268–289. ISBN 978-0-87021-906-1.

- Roskill, Stephen (1976). Naval Policy Between the Wars. Vol. 1. London: Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-211561-2.

- Shepherd, R. C., ed. (February 1915). "Schedule of Operations of the Atlantic Fleet, and Preliminary Arrangements Incident to the Panama–San Francisco Cruise". Our Navy. VIII (10). New York: Our Navy Publishing Co.: 28–29. OCLC 41114005.

- Sturton, Ian (1985). "Spain". In Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 375–382. ISBN 978-0-85177-245-5.

Further reading

- Lyon, Hugh (1978). Encyclopedia of the World's Warships: A Technical Directory of Major Fighting Ships from 1900 to the Present Day. London: Salamander Books. ISBN 978-0-86101-007-3.