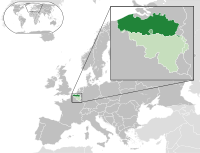

The Dutch language used in Belgium can also be referred to as Flemish Dutch or Belgian Dutch ( Dutch: Vlaams Nederlands, Belgisch Nederlands). Dutch is the mother tongue of about 60% of the population in Belgium, spoken by approximately 6.5 million out of a population of 11 million people. [1] [2] [3] It is the only official language in Flanders, that is to say the provinces of Antwerp, Flemish Brabant, Limburg, East Flanders and West Flanders. Alongside French, it is also an official language of Brussels. However, in the Brussels Capital Region and in the adjacent Flemish-Brabant municipalities, Dutch has been largely displaced by French as an everyday language. [4] [5]

Belgian Dutch differs from Standard Dutch in terms of accent and vocabulary. The most spoken Dutch dialects in Belgium are West Flemish, East Flemish, Brabantian and Limburgish. [6] [7] Although the Brabant dialect has historically been associated with working-class areas of Brussels, in particular the Marolles, the virtual disappearance of those populations means that linguistic variants in which an influence of the Brabant can be discerned exist in a diminishing degree.

Changes and conflicts

The position of Dutch in Belgium has improved considerably over the past 50 years at the expense of French, which once dominated strongly in political, economic and cultural life. The main reasons for this are the strengthened economic position of Flanders and the problematic situation of heavy industry in Wallonia since the 1960s.

The position of Standard Dutch as a general language has been reinforced at the expense of the previously almost exclusive use of the dialects as spoken languages. Incidentally, the status of standard Dutch in speech is floating, which means that it is used at socially higher levels according to the rules that are also applicable in the Netherlands, but at lower social levels, and especially locally, many gradations of dialect are used.

For a long time a Flemish standard has existed as a close variant of Standard Dutch existence, the so-called Schoonvlaams. The spoken standard was also under the influence of Antwerp for a long time as a dialect with high status, which also applied outside this city. The high quality of Dutch-speaking schools is an explanation for the growing success of the Dutch-speaking educational network in Brussels. On the other hand, French-speaking education has had a lower status due to the massive influx of non-French-speaking children.

Knowledge of French as a second language among Dutch speakers in Flanders is decreasing, especially to the benefit of English. In Flemish education, as opposed to Dutch in Wallonia, French is still a compulsory second language. [8] In schools in Wallonia, Dutch is often offered only as an option, and as such it must compete against English. There are also Walloon educational institutions where several subjects are taught in Dutch as a form of language immersion.

Despite its name, Brabantian is the dominant contributor to the Flemish Dutch tussentaal. The combined region, culture, and people of Dutch-speaking Belgium have come to be known as "Flemish". [9] Flemish is also used to refer to one of the historical languages spoken in the former County of Flanders. [10] Linguistically and formally, "Flemish" refers to the region, culture and people of (North) Belgium or Flanders. Flemish people speak (Belgian) Dutch in Flanders, the Flemish part of Belgium.

By region

Brussels

The Brussels-Capital Region is officially bilingual French–Dutch. This means that Dutch should be on an equal footing with French, which is often not the case at local Brussels level: in many municipal and regional services, hospitals, public transport, and also in shops and offices, Dutch is little used. On the other hand, Dutch in Brussels is important because the Flemish government resides there, alongside the federal government services, and especially because many Flemish people work in Brussels, but do not live there.

The last official census count in Brussels dates from 1947. At that time, the proportions were 24.24% Dutch-speaking and 70.61% French-speaking. Since then no official census has been conducted. These were abolished under Flemish political pressure because they were often unreliably performed and could not substantiate further 'minorizing' of Dutch. Since then, it has been necessary to rely on different sources to get the number of Dutch and French speakers in Brussels. Dutch speakers tend to congregate in the city's northern municipalities.

Languages spoken at home as determined by a 2013 survey are: [11]

- French: 38.1%

- French and other language: 23.2%

- Dutch and French: 17.0%

- Neither Dutch nor French: 16.5%

- Dutch: 5.2%

In the last decade Dutch seems to be used more, both in education, where this development has been going on for some time, and in economic and social life. In 2012, 35% of the higher education institutions in Brussels were Dutch-speaking. The percentage of participants in nursery and primary education who received Dutch lessons approached 25% in 2013. The percentage of participants in secondary and higher education who received Dutch lessons was also on the rise and in 2013 reached 17%. Among foreign inhabitants of Brussels, there is also a clear increase in both the number and percentage of children and adults choosing Dutch-speaking education. [12]

Flanders

Dutch is the official language in Flanders, but there are a number of Flemish municipalities in the Brussels Periphery with a French-speaking majority, which are officially Dutch-speaking with French-language facilities. [13] [14] [15] [16]

The number of people in Flanders who submitted their vehicle registration in French in 2010 is six times higher than the number of Dutch-language applications in Wallonia. [17]

Wallonia

To the east of the Flemish counties Voeren, in the Low Dietsch region in the Liège province, a transitional dialect between Dutch and German is still being spoken. This regional language is closely related to that of Dutch South Limburgish, the dialect of Eupen and of the adjacent Aachen. These rural municipalities, which have been able to preserve their 'Platdietse' character despite two centuries of French-speaking administration, remained officially monolingual French after the establishment of the language border in 1963, although there is a legal possibility for facilities for Dutch or German. In the last three decades more and more Germans working in Aachen have settled in this region. They do not reinforce the Dutch language but a German language element.

There has also been a considerable linguistic deviation of Flemish workers with their families to the Borinage and the Liège industrial areas. This immigration took place from the 19th to the middle of the 20th century. These were mostly dialect speakers who had little or no knowledge of Standard Dutch and became French-speaking quite quickly. The conservative Belgian government and especially the Catholic clergy also saw such 'social risks' for Flanders in the rise of socialism in these industrial areas, and therefore stimulated train and tram traffic, which allowed the Flemish to continue to live in their own environment.

In the years after the Second World War, many Flemish farmers also moved to Wallonia, often because of the size of the farms and the attractive price of agricultural land. Dutch has also become more important in tourism, especially in the Ardennes. The Flemish and Dutch are increasingly serviced at campsites, hotels and attractions in their own language by Dutch-speaking staff. There are also more Flemish families now living across the language border because it is cheaper to build, buy or rent. These developments do not yet lead to legal facilities for Dutch speakers.

Characteristics

Dutch is the majority language in northern Belgium, being spoken natively by three-fifths of the population of Belgium. It is one of the three national languages of Belgium, together with French and German, and is the only official language of the Flemish Region.

The various Dutch dialects spoken in Belgium contain a number of lexical and a few grammatical features which distinguish them from Standard Dutch. [18] As in the Netherlands, the pronunciation of Standard Dutch is affected by the native dialect of the speaker.

All Dutch dialect groups spoken in Belgium are spoken in adjacent areas of the Netherlands as well. East Flemish forms a continuum with both Brabantic and West Flemish. Standard Dutch is primarily based on the Hollandic dialect [19] (spoken in the Western provinces of the Netherlands) and to a lesser extent on Brabantian, which is the dominant dialect in Flanders, as well as in the south of the Netherlands.

The supra-regional, semi-standardized colloquial form of Dutch spoken in Belgium uses the vocabulary and the sound inventory of the Brabantic dialects. It is often called Tussentaal ("in-between-language" or "intermediate language", intermediate between dialects and standard Dutch). [20]

See also

References

- ^ "ATLAS - Dutch: Who speaks it?". UCL. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- ^ "Belgium Bickering Over French and Dutch, Its Dual Languages". Los Angeles Times. 20 February 2005. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- ^ "About Belgium - Language Matters". Beer Tourism. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- ^ Harbert, The Germanic Languages, CUP, 2007

- ^ Jan Kooij, "Dutch", in Comrie, ed., The World's Major Languages, 2nd ed. 2009

- ^ "Belgium: A nation divided". The Independent. 18 December 2007. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ^ Leidraad van de Taaltelefoon. Dienst Taaladvies van de Vlaamse Overheid (Department for Language advice of the Flemish government).

- ^ "Walen moeten meer Nederlands leren". Vrt Flemish Public Broadcaster. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ "Vlaams". Ethnologue. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^ König & Auwera, eds, The Germanic Languages, Routledge, 1994

- ^ (in Dutch) Janssens, Rudi, BRIO-taalbarometer 3: diversiteit als norm (pdf), Brussels Informatie-, Documentatie- en Onderzoekscentrum, 2013.

- ^ "bruselo.info". www.bruselo.info. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

-

^

"Dubbel zoveel Franstalige rechtszaken dan Nederlandstalige in BHV".

Concreet schreef de rechtbank van eerste aanleg in 2010 ruim 20.300 Franstalige zaken in, tegenover bijna 9.900 Nederlandstalige dossiers. Bij de arbeidsrechtbank telde men meer dan 15.900 Franstalige zaken, tegenover ruim 5.800 Nederlandstalige zaken.

- ^ Libre.be, La (July 6, 2011). "Deux fois plus d'affaires inscrites au rôle en français qu'en néerlandais à BHV". www.lalibre.be. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

-

^

"Verfransing en ontnederlandsing van faciliteitengemeenten gaat nog steeds verder".

Afgaande op deze gegevens zou 78% van de bevolking van de faciliteitengemeenten Franstalig zijn.

-

^

"7,6 % du personnel médical à Bruxelles est néerlandophone".

[...] dans le Brabant flamand. En 2010, 16,75 % des dispensateurs étaient enregistrés comme francophones par l'Inami. [...] C'est surtout dans les communes à facilités que cela se marque. Les chiffres de la ministre des Affaires sociales révèlent qu'en 2010, 77,17 % des prestataires de soins actifs à Drogenbos, Linkebeek, Kraainem, Rhode-Saint-Genèse, Wemmel et Wezembeek-Oppem sont recensés comme des francophones par l'Inami et s'adressent en français à lui.

-

^

"93,7% des immatriculations enregistrées en français à Bruxelles".

Il est également ressorti des chiffres qu'il y a nettement plus de demandes d'immatriculation libellées en français en Flandre (31.921, dont 22.959 dans le Brabant flamand) qu'il y en a en néerlandais en Wallonie (5.187).

- ^ G. Janssens and A. Marynissen, Het Nederlands vroeger en nu (Leuven/Voorburg 2005), 155 ff.

- ^ "De gesproken standaardtaal: het Algemeen Beschaafd Nederlands". Structuur en geschiedenis van het Nederlands Een inleiding tot de taalkunde van het Nederlands (in Dutch). Niederländische Philologie, Freie Universität Berlin. 2014-06-10. Retrieved 2015-08-10.

- ^ "Geeraerts, Dirk. 2001. "Een zondagspak? Het Nederlands in Vlaanderen: gedrag, beleid, attitudes". Ons Erfdeel 44: 337-344" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-25. Retrieved 2012-01-19.