This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section

has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{

in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was

last edited by

FeralOink (

talk |

contribs) 71 seconds ago. (

Update timer) |

The Decline of the Mughal Empire was a period in Indian History roughly between the early 18th century and mid 19th Century where the Mughal Empire, which once dominated the subcontinent, experienced a large scale decline. There are various factors responsible for this decline such as internal conflicts, Maratha, Afghan and Persian Invasions and British colonialism.

Causes of Decline

The cause of decline of Mughal Power has ben a debate among historians. Various factors including rebellions and orthodox religious policies have been asserted as a cause of decline

Several Historians assert such orthodox policies resulting in decline of Mughal power in the Indian Subcontinent. [1] During the reign of Aurangzeb imposed practices of orthodox Islamic state based on the Fatawa 'Alamgiri. This resulted in the persecution of Shias, Sufis and non-Muslims [2] [3] G. N. Moin Shakir and Sarma Festschrift argue that he often used political opposition as pretext for religious persecution, resulting in revolts of groups of Jats, Marathas, Sikhs, Satnamis and Pashtuns . [4] [5] [6]

Aurangzeb's son, Bahadur Shah I, repealed the religious policies of his father and attempted to reform the administration. "However, after he died in 1712, the Mughal dynasty began to sink into chaos and violent feuds. In 1719 alone, four emperors successively ascended the throne. [7]

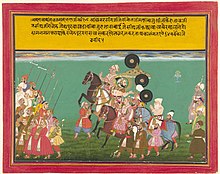

Mughal war of succession (1707–1709)

Following the Deccan Wars, the three sons of Aurangzeb Bahadur Shah I, Muhammad Azam Shah, and Muhammad Kam Bakhsh fought each other for the throne. Muhammad Azam Shah lived in Ahmednagar. Khafi Khan suggested that whoever reached the capital city of Agra first would capture the throne. [8] The distances to Agra from Jamrud and Ahmednagar were 715 and 700 miles, respectively. Azam Shah and Bahadur Shah were involved in the Battle of Jajau, south of Agra, on 20 June 1707. [9] Azam Shah and his three sons were killed in the battle and were buried with other royals in Humayun's Tomb in Delhi. [10]

Bahadur Shah's half-brother, Muhammad Kam Bakhsh, marched to Bijapur in March 1707 with his soldiers. When the news of Aurangzeb's death spread through the city, the city's monarch, King Sayyid Niyaz Khan surrendered the fort to Baksh without a fight. [11] In May 1708, Bahadur Shah sent a letter to Kam Bakhsh warning that he hoped would prevent him from proclaiming himself an independent sovereign. Bahadur Shah then began a journey to the Tomb of Aurangzeb to pay his respects to his father. [12] Kam Bakhsh replied, thanking him "without either explaining or justifying [his actions]". [13]

When Bahadur Shah reached Hyderabad on 28 June 1708, he learned that Kam Bakhsh had attacked Machilipatnam (Bandar) in an attempt seize over three million rupees worth of treasure hidden in its fort. The subahdar of the province, Jan Sipar Khan, refused to hand over the money. [13] Enraged, Kam Bakhsh confiscated his properties and ordered the recruitment of four thousand soldiers for the attack. [14] In July, the garrison at the Gulbarga Fort declared its independence and garrison leader Daler Khan Bijapuri "reported his desertion from Kam Bakhsh". On 20 December 1708, Kam Bakhsh marched towards Talab-i-Mir Jumla, on the outskirts of Hyderabad, with "three hundred camels, [and] twenty thousand rockets" for war with Bahadur Shah. Although Kam Bakhsh had little money and few soldiers left, the royal astrologer had predicted that he would "miraculously" win the battle. [15] At sunrise the following day, Bahadur Shah's army charged towards Kam Bakhsh. His 15,000 troops were divided into two bodies: one led by Mumin Khan, assisted by Rafi-ush-Shan and Jahan Shah, and the second under Zulfiqar Khan Nusrat Jung. Two hours later Kam Bakhsh's camp was surrounded, and Zulfiqar Khan impatiently attacked him with his "small force". [16] With his soldiers outnumbered and unable to resist the attack, Kam Bakhsh joined the battle and shot two quivers of arrows at his opponents. A dispute arose between Mumin Khan and Zulfikar Khan Nusrat Jung over who had captured them, with Rafi-us-Shan ruling in favor of the latter. [17] Bahadur Shah I was crowned the Mughal empire after the conflicts.

Later Civil Wars

After the death of Bahadur Shah I, a war of succession brow out between his sons in which Jahandar Shah was victorious. Unlike previous Mughal wars of succession, the outcome of this war was engineered by a noble, Zulfiqar Khan. He built an alliance between Jahandar Shah, and his younger brothers Rafi-us-Shan and Jahan Shah, proposing to them that they could divide the empire between them upon victory (with Zulfiqar Khan serving as their common mir bakhshi). Azim-us-Shan was defeated and killed, following which Jahandar Shah broke the alliance and turned on his brothers, defeating them and killing them with the help of Zulfiqar Khan, emerging as the victor of the succession struggle. [18] [19]

Farrukhsiyar defeated Jahandar Shah with the aid of the Sayyid brothers, and one of the brothers, Abdullah Khan. According to historian William Irvine, Farrukhsiyar's close aides Mir Jumla III and Khan Dauran sowed seeds of suspicion in his mind that they might usurp him from the throne. [20] [21]

Syed Brothers

During the reign of the Aurangzeb in 1697, Hassan Ali Khan and Hussain Ali Khan were appointed into Mughal administration. [22] [23] They were Indian Muslims belonging to the Sadaat-e-Bara clan of the Barha dynasty, who claimed to be Sayyids or the descendants of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. [24] The brothers became highly influential in the Mughal Court after Aurangzeb's death in 1707 and became de facto sovereigns of the empire when they began to make and unmake emperors. [25] [26]

After Prince Mu'izz ud-Din Jahandar Shah, the eldest of Emperor Bahadur Shah's sons, had been appointed in 1695 to the charge of the Multan province. [27] When Emperor Aurangzeb died and Prince Muhammad Mu'azzam Shah Alam, reached Lahore on his march to Agra to contest the throne, the Sayyids presented themselves, and their services were gladly accepted. In the Battle of Jajau or Jajowan on the 18th Rabi I, 1119 H. (18 June 1707), they served in the vanguard and fought valiantly on foot, as was the Sayyid habit in an emergency. [28] The two Sayyids managed to quarrel with Khanazad Khan, the vizier Munim Khan's second son, and offended Jahandar Shah, though the breach was healed by a visit to them from the vizier in person, there is little doubt that this difference helped to keep them out of employment . [29]

Rajput Rebellions

In the 18th century, various Rajput noblemen previously loyal to the Mughal crown, revolted and carved out their own independent kingdoms. These revolts lasted throughout the 18th and 19th centuries.

Rajput Rebellion of 1708–1710

Various Rajput nobles including Ajit Singh, Amar Singh II, Maharaja Jai Singh II and Durgadas Rathore formed an alliance and revolted against the Mughal crown in 1708. [30]

Bahadur Shah I was forced to move south and could not come back till 12 June 1710. Jodhpur was captured in July and Amber in October 1708. [31] Sayyid Hussain Barha and Churaman Jat were sent with a large force to retake Amber, however Barha was shot dead with his brothers and the Mughals were defeated. Three thousand Mughals were killed at Sambhar. Jai Singh in his letter to Chattrasal has written that "among the dead were all three Faujdars". The Rajputs also took all the Mughal treasury of Sambhar and distributed it among the people. [30] When Bahadur Shah got to know of this defeat, he immediately tried to sue for peace by offering to restore Ajit Singh and Jai Singh to their thrones, however the Rajputs demanded the restoration of their lands that had been forcefully taken by Aurangzeb in 1679 and the expulsion of the Mughals from Rajputana. [30]

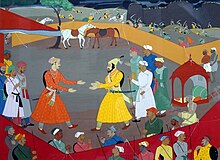

When Bahadur Shah returned, he had no choice but to negotiate with the Rajputs. Gifts and letters were sent to the two rebel Rajas in May 1710. The rise of Banda Singh Bahadur and death of Wazir Khan, faujdar of Sirhind, further caused fear in the Mughal court and on 11 June 1710 Jai Singh and Ajit Singh were invited to the Mughal court and were given robes of honour, presents and governorships of Malwa and Gujarat.

War with the Marathas

Early Conflicts

The Maratha Empire was founded by Shivaji. [32] He led a resistance against the Sultanate of Bijapur in 1645 by winning the fort Torna, followed by many more forts, placing the area under his control. He created an independent Maratha kingdom with Raigad as its capital [33] and successfully fought against the Mughals to defend his kingdom.

In 1665 the Marathas Under Shivaji sacked Surat, a wealthy Mughal port city. The Maratha soldiers took away cash, gold, silver, pearls, rubies, diamonds & emeralds from the houses of rich merchants such as Virji Vora, Haji Zahid Beg, Haji Kasim and others. The business of Mohandas Parekh, the deceased broker of the Dutch East India Company, was spared as he was reputed as a charitable man. [34] [35] In 1660 in the Shaista Khan defeated Maratha forces under Firangoji Narsala. [36] Shaista Khan's residence in Pune was later attacked by Shivaji. Mughal Commander Jai Singh defeated Shivaji in Battle of Purandar in 1665. [37]

Deccan Wars

Mughal and Maratha Forces clashed in the 27 years long Deccan Wars. [38] Shivaji's son Sambhaji enguaged rebellion against the Mughal state and service to the Mughal sovereign in an official capacity. [39] It was common practice in late 17th-century India for members of a ruling family of a small principality to both collaborate with the Mughals and rebel. [39]

In 1681, Sambhaji was contacted by Prince Akbar, the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb's son, who was keen to enter into a partnership with the Marathas in order to assert his political power againt his ageing father's continuing dominance. [38] Akbar spent several years under the protection of Sambhaji but eventually went into exile to Persia in 1686. Sambhaji was later executed by Mughal forces in 1689. [40] [38] at the age of 31. His death was a significant event in Indian history, marking the end of the golden era of the Maratha Empire. Sambhaji's wife and minor son, later named Shahuji was taken into the Mughal camp, and Rajaram, who was now an adult, was re-established as ruler; he quickly moved his base to Gingee, far into the Tamil country. [38] From here, he was able to frustrate Mughal advances into the Deccan until 1700. On 1689, Sambhaji's son Shahu was taken prisoner along with his mother by Mughals after the Battle of Raigarh. [41] [42]

Constant warfare in Deccan, especially with the Marathas, largely contributed in the bankruptcy and decline of the Mughal Empire. [43] The Indologist Stanley Wolpert, emeritus professor at UCLA, [44] says that:

The conquest of the Deccan, to which Aurangzeb devoted the last twenty-six years of his life, was in many ways a Pyrrhic victory, costing an estimated hundred thousand lives a year during its last decade of fruitless, chess-game warfare ... The expense in gold and rupees can hardly be imagined or accurately estimated. Alamgir's moving capital alone-a city of tents thirty miles in circumference, two hundred and fifty bazaars, with half a million camp followers, fifty thousand camels, and thirty thousand elephants, all of whom had to be fed, stripped peninsular India of any and all of its surplus grain and wealth ... Not only famine, but bubonic plague arose ... Even Alamgir had ceased to understand the purpose for it all by ... 1705. The emperor was nearing ninety by then ... "I came alone and I go as a stranger. I do not know who I am, nor what I have been doing," the dying old man confessed to his son in February 1707. [45]

Maratha Invasions

In 1707, Emperor Aurangzeb died and Shahu was recognized by the Mughal Emperors as the rightful heirs to Shivaji. [46] Over the 18th century Maratha Forces invaded and conquered former Mughal territories.

Shahu appointed Balaji Vishwanath as Peshwa in 1713. In 1719, Marathas under Balaji marched to Delhi with Sayyid Hussain Ali, the Mughal governor of Deccan, and deposed the Mughal emperor, Farrukhsiyar. [47]The new teenaged emperor, Rafi ud-Darajat and a puppet of the Sayyid brothers, granted Shahu rights to collecting Chauth and Sardeshmukhi from the six Mogul provinces of Deccan, and full possession of the territories controlled by Shivaji in 1680. [48] [49]

After Balaji Vishwanath's death in April 1720, his son, Bajirao I, was appointed Peshwa by Shahu. Bajirao is credited with expanding the Maratha Empire tenfold from 3% to 30% of the modern Indian landscape during 1720–1740. He fought over 41 battles before his death in April 1740 and is reputed to have never lost any. [50] The Battle of Palkhed was a land battle that took place on 28 February 1728 at the village of Palkhed, near the city of Nashik, Maharashtra, India between Baji Rao I and Qamar-ud-din Khan, Asaf Jah I of Hyderabad. The Marathas defeated the Nizam. The battle is considered an example of the brilliant execution of military strategy. [47] In 1737, Marathas under Bajirao I raided the suburbs of Delhi in a blitzkrieg in the Battle of Delhi (1737). [51] [52] The Nizam set out from the Deccan to rescue the Mughals from the invasion of the Marathas, but was defeated decisively in the Battle of Bhopal. [53] [54] The Marathas extracted a large tribute from the Mughals and signed a treaty which ceded Malwa to the Marathas. [55] Raghuji I of Nagpur undertook six expeditions into Bengal from 1741 to 1748. [56] In 1743, the Nizam recaptured Tiruchirappalli from the Maratha forces in the Siege of Trichinopoly. [57] Alivardi Khan, the Nawab of Bengal made peace with Raghuji in 1751 ceding Cuttack up to the river Subarnarekha, and agreeing to pay Rs. 1.2 million annually as the Chauth for Bengal and Bihar. [58]

By 1760 Delhi had been sacked several times, and there was an acute shortage of supplies in the Maratha camp. Sadashivrao Bhau ordered the sacking of the already depopulated city. [59] [60] He is said to have planned to place his nephew and the Peshwa's son, Vishwasrao, on the Mughal throne. By 1760, with the defeat of the Nizam in the Deccan, Maratha power stretched across large parts of former Mughal territory. [61] In 1761, Maratha power in Northern India declined following the Third Battle of Panipat. [62]

In 1771, Mahadaji Shinde recaptured Delhi from the Rohilla Pashtuns. Shinde captured the family of Zabita Khan, desecrated the grave of Najib ad-Dawlah and looted his fort. [63] With the fleeing of the Rohillas, the rest of the country was burnt, with the exception of the city of Amroha, which was defended by some thousands of Amrohi Sayyid tribes. [64] Hafiz Rahmat Khan Barech sought assistance in an agreement formed with the Nawab of Oudh, Shuja-ud-Daula, by which the Rohillas agreed to pay four million rupees in return for military help against the Marathas. Hafiz Rehmat sought an alliance with Awadh to keep the Marathas out of Rohilkhand. However, after he refused to pay, Oudh attacked the Rohillas. [65]

In 1784, Shinde installed Shah Alam II as a puppet ruler on the Mughal throne. [66] Shinde receiving in return the title of deputy Vakil-ul-Mutlak or vice-regent of the Empire. The Mughals also gave him the title of Amir-ul-Amara (head of the amirs). [67] After taking control of Delhi, the Marathas sent a large army in 1772 to punish Afghan Rohillas for their involvement in Panipat. Their army devastated Rohilkhand by looting and plundering as well as taking members of the royal family as captives. [66]

Later Conflicts

The Marathas had lost control of Delhi in 1803 to the East India Company during the Second Anglo-Maratha War. [68] In 1804, Mughal forces under Shah Alam II, allied with the East India Company, engaged with Maratha forces in Delhi. Yashwantrao Holkar confronted the British commander David Ochterlony. Holkar abandoned the siege after reinforcements led by Gerard Lake arrived on 18 October. [69] With this victory, Shah Alam II retained control over Delhi under protection of the East India Company. [69]

Nader Shah's Invasion of India

Emperor Nader Shah,of the Afsharid dynasty, invaded large parts of Northern India including Delhi. His army had easily defeated the Mughals at the Battle of Karnal and would eventually capture the Mughal capital in the aftermath of the battle. [70]

Battle of Khyber Pass

Mughal and Afsharid forces Faught the Battle of Khyber Pass 1738. This was an overwhelming victory for the Persians, opening up the path ahead to invade the crown-lands of the Mughal Empire of Muhammad Shah. On November 26 from near Jalalabad, the Persian army arrived at Barikab (33 kilometres from the Khyber Pass) where Nader divided his army leaving his son Nasrollah Mirza behind with the bulk of the forces at his disposal and sending forth 12,000 men to the Khyber Pass under Nasrollah Qoli whilst he gathered a 10,000 light cavalry under his direct command. Beginning an epic flank-march of over 80 kilometres through some of the most unnavigable terrain in Asia, Nader reached close to Ali-Masjed where the 10,000 troops of his army curved their route of march northwards and onto the eastern end of the Khyber Pass. [71]

As the reports reached the Mughal high command, disagreement arose as to whether these calls for reinforcement ought to be answered. Muhammad Shah was eager to join Sa'adat Khan in the field, but his two chief advisers, Nizam-ul-Mulk and Khan Dowran, advised caution against rash decisions. Khan-i Dauran declared that it was not the Indian style to abandon a friend, even if he was imprudent. [72] The initial total of men leaving the Mughal camp alongside Khan Dowran was 8,000–9,000 men, mostly cavalry with some musket-bearing infantry. A steady stream of reinforcements left the Mughal encampment to cross the Alimardan river and join battle throughout the day, but there was no effort to bring these large numbers under a unified deployment east of the Alimardan river in support of Mughal units already engaged. Instead, the Mughals at the front would receive a continuous line of reinforcements with no grand tactical plan to help direct them. [73]

Battle of Karnal

On 24 February 1739 Mughal and Afsharid forces Faught the Battle of Karnal [74] Nader observed the massacre from behind the main line of jazāyers as they fired volley after volley into the reeling enemy before them. The cavalry of Khan Dowran, consisting of Indian Muslims, [75] looked down on fighting with muskets with contempt, which was a talent of the mostly Hindu infantrymen in India. [76] [77] They prided themselves on sword-play and fancy-riding, while musketeers were not given importance in the Mughal military compared to Iran. [78] [79] The heavy bullets of the jazāyer muskets, and the even more powerful cannonballs of the zamburaks, easily penetrated the armour of the war elephants. Many nobles were killed and captured amongst the Mughals; Khan Dowran himself was struck. Badly injured, he fell from his elephant as his own blood splattered over him, prompting his remaining retainers to scramble to his aid. [80]

Tahmasp Khan Jalayer, in command of the Persian right, did not engage until this phase in the battle and began wrapping his forces around the left flank of Sa'adat Khan's men from the north. After two hours of intense fighting in the centre, Sa'adat Khan's war elephant became entangled with another and in the frenzy a Persian soldier climbed the side of the Khan's beast and implored him to surrender. Being caught in an impossible set of circumstances Sa'adat Khan decided to lay down his arms. Unwilling to engage the Mughals on disadvantageous ground Nader re-established his lines in the valley to the east. [81] Muhammad Shah urged the Nizam to help Khan Dowran, but the Nizam moved no further and ignored all pleas for action. [82]

Sacking of Delhi

Nader entered Delhi with Mohammed Shah as his vassal on 20 March 1739. The person of the Shah was accompanied by 20,000 Savaran-e Saltanati (royal guard), and 100 war elephants mounted by his Jazāyerchi. Rumors began spreading amongst the populace of Delhi that a gratuitous levy was imminent. Nader sent out a fowj (a thousand-strong unit) but ordered them to engage only those involved in the violence. [83] [84] Nader sent forth 1,000 cavalrymen to each district of the city to ensure the collection of taxes. But perhaps the greatest riches were plundered from the treasuries of the Mughal dynasty's capital. The Peacock Throne was also taken away by the Persian army, and thereafter served as a symbol of Persian imperial might. Among a trove of other fabulous jewels, Nader also gained the Koh-i-Noor ("Mountain of Light") and Darya-ye Noor ("Sea of Light") diamonds. It is estimated that the total worth of the treasures plundered was perhaps 700 million rupees. [85]

Persian troops left Delhi at the beginning of May 1739, also taking with them thousands of elephants, horses, and camels, all loaded with the booty they had collected. The plunder seized from India was so rich that Nader stopped taxation in Persia for a period of three years following his return. [86] On Nader's return to Iran, Sikhs fell upon Nader's army and seized a large amount of booty and freed the slaves in captivity. [87] [88] [89] [90]

Losses and consequences

The Mughals suffered far heavier casualties than the Persians. Exact figures are uncertain as accounts of that period were prone to bombast. Various contemporary commentators estimated Mughal casualties being up to 30,000 men slain with most agreeing on a figure of around 20,000 and with Axworthy giving an estimate of roughly 10,000 Mughal soldiers killed. Nader himself claimed that his army slew 20,000. [91] The number of Mughal officers slain amounted to a staggering 400. [92] The Mughals had been defeated in part due to their outdated cannons. In addition, Indian elephants were an easy target for Persian artillery and Persian troops were more skilled with a musket. [93]

The city of Delhi was sacked for several days. An enormous fine of 20 million rupees was levied on the people of Delhi. Muhammad Shah handed over the keys to the royal treasury, and lost the Peacock Throne, to Nader Shah, which thereafter served as a symbol of Persian imperial might. Amongst a treasure trove of other fabulous jewels, Nader also gained the Koh-i-Noor and Darya-i-Noor ("Mountain of Light" and "Sea of Light", respectively) diamonds; they are now part of the British and Iranian Crown Jewels, respectively. Nader and his Afsharid troops left Delhi in the beginning of May 1739, but before they left, he ceded back all territories to the east of the Indus, which he had overrun, to Muhammad Shah. [94]

European Colonialism

From the 17th to 19th Centuries, the British and French East India Company faught several proxy wars with the Mughal Empire and its successor states. [95] The British were overall victorious. This led to the weakening of the empire's power and economy.

Anglo-Mughal war

In 1682 the English East India Company sent William Hedges to Shaista Khan, the Mughal governor of Bengal Subah to grant the company trading privileges. causing Emperor Aurangzeb to break off the negotiations. After that Child decided to go to war against the Mughals. [96]

In 1685, after some breaking of negotiations by Sir Josiah Child, Bt, the Governor of Bengal reacted by increasing the tributaries of the trade with the north-east from 2% to 3.5%. The company established a fortified enclave throughout the region, and attain independence of the surrounding subah from the Mughal territory by bringing the local governors and the Hooghly River to their control, which would later allow to form relationships with the Kingdom of Mrauk U based in Arakan (today's Myanmar) and hold substantial power in the Bay of Bengal. [97]

Upon request, King James II [98] sent warships to the company based in India, but the expedition failed. [99] Following the dispatch of twelve warships loaded with troops, a number of battles took place, leading to the Siege of Bombay Harbour and bombardment of the city of Balasore. New peace treaties were negotiated, and the East India Company sent petitions to the emperor, Aurangzeb. [100]

The English naval forces established a blockade of the Mughal ports on the western Indian coast and engaged in several battles with the Mughal Army, and ships with Muslim pilgrims to Arabia's Mecca were also captured. [101] [100] [102] The East India Company navy blockaded several Mughal ports on the western coast of India and engaged the Mughal Army in battle. The blockade started to effect major cities like Chittagong, Madras and Mumbai (Bombay), which resulted in the intervention of Emperor Aurangzeb, who seized all the factories of the company and arrested members of the East India Company Army, while the Company forces commanded by Sir Josiah Child, Bt captured further Mughal trading ships. [103]

In 1689, the strong Mughal fleet from Janjira commanded by Yakut Khan and blockaded the East India Company fort in Bombay. After a year of resistance, a famine broke out due to the blockade, the Company surrendered, and in 1690 the company sent envoys to Aurangzeb's court to plea for a pardon and to renew the trade firman [104] Ultimately the Company was forced to concede by the armed forces of the Mughal Empire and the company was fined 150,000 rupees (roughly equivalent to today's $4.4 million). The company's apology was accepted and the trading privileges were reimposed by Aurangzeb. [105] [106] [107]

Carnatic Wars

The Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb died in 1707. He was succeeded by Bahadur Shah I, but there was a general decline in central control over the empire during the tenure of Jahandar Shah and later emperors. Nizam-ul-Mulk established Hyderabad as an independent kingdom. Several erstwhile Mughal territories were autonomous such as the Carnatic, ruled by Nawab Dost Ali Khan Dost Ali's death sparked a power struggle between his son-in-law Chanda Sahib, supported by the French, and Muhammad Ali, supported by the British. [108]

In 1740, the First Carnatic War broke out as a part of the War of the Austrian Succession. [108] Great Britain was drawn into the war in 1744, opposed to France and its allies. [109] In July 1746, French commander La Bourdonnais and British Admiral Edward Peyton fought an indecisive action off Negapatam, after which the British fleet withdrew to Bengal. On 21 September 1746, the French captured the British outpost at Madras. La Bourdonnais had promised to return Madras to the British, but Joseph François Dupleix withdrew that promise, and wanted to give Madras to Anwar-ud-din after the capture. The Nawab, Anwaruddin Khan, then sent a 10,000-man army to take Madras from the French but this was repulsed in the Battle of Adyar. The French then made several attempts to capture the British Fort St. David at Cuddalore, but were halted. British Admiral Edward Boscawen besieged Pondicherry in the later months of 1748, but lifted the siege with the advent of the monsoon rains in October. [108]

The siege was lifted in October 1748 with the arrival of the monsoon, and the war came to a conclusion with the arrival in December of news of the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle. Under its terms Madras was returned to British control. [110]

The Second Carnatic War broke out in 1749. On one side was Nasir Jung, the Nizam and his protege Muhammad Ali, supported by the British, and on the other was Chanda Sahib and Muzaffar Jung, supported by the French, vying to become the Nawab of Arcot. Muzaffar Jung and Chanda Sahib were able to capture Arcot while Nasir Jung's subsequent death allowed Muzaffar Jung to take control of Hyderabad. In 1751, however, Robert Clive led British troops to capture Arcot. The war ended with the Treaty of Pondicherry, signed in 1754, which recognised Muhammad Ali Khan Walajah as the Nawab of the Carnatic. [108]

The outbreak of the Seven Years' War in Europe in 1756 resulted in renewed conflict between French and British forces in India. This started the Third Carnatic War in 1757. This war beyond southern India and into Bengal where British forces captured the French settlement of Chandernagore in 1757. However, the war was decided in the south, where the British successfully defended Madras, and Sir Eyre Coote decisively defeated the French, commanded by the Comte de Lally at the Battle of Wandiwash in 1760. After Wandiwash, Pondicherry fell to the British in 1761. [108]

Battle of Plassey

The Battle of Plassey was Faught British East India Company, under the leadership of Robert Clive and the Nawab of Bengal and his French allies on 1757. [111] Clive defeated Siraj-ud-Daulah at Plassey in 1757 and captured Calcutta. [112] The victory was made possible by the defection of Mir Jafar, Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah's commander in chief. [113]

The battle took place at Palashi south of Murshidabad in West Bengal, then capital of Bengal Subah. The belligerents were the British East India Company, and the Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah, the last independent Nawab of Bengal. He succeeded Alivardi Khan (his maternal grandfather). Siraj-ud-Daulah had become the Nawab of Bengal the year before, and he had ordered the English to stop the extension of their fortification. Robert Clive bribed Mir Jafar, the commander-in-chief of the Nawab's army, and also promised to make him Nawab of Bengal. Clive defeated Siraj-ud-Daulah at Plassey in 1757 and captured Calcutta. [114]

The battle was preceded by an attack on British-controlled Calcutta by Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah and the Black Hole massacre. The British sent reinforcements under Colonel Robert Clive and Admiral Charles Watson from Madras to Bengal and recaptured Calcutta. Clive then seized the initiative to capture the French fort of Chandannagar. [115]

On 9 January 1757, a force of 650 men under Captain Coote and Major Kilpatrick stormed and sacked the town of Hooghly, 23 miles (37 km) north of Calcutta. [116] On learning of this attack, the Nawab raised his army and marched on Calcutta, arriving with the main body on 3 February and encamping beyond the Maratha Ditch. Siraj set up his headquarters in Omichund's garden. A small body of their army attacked the northern suburbs of the town but were beaten back by a detachment under Lieutenant Lebeaume placed there, returning with fifty prisoners. [117] [118] [119] [120] [121]

Clive decided to launch a surprise attack on the Nawab's camp on the morning of 4 February. The attack scared the Nawab into concluding the Treaty of Alinagar with the Company on 9 February, agreeing to restore the Company's factories, allow the fortification of Calcutta and restoring former privileges. The Nawab withdrew his army back to his capital, Murshidabad. [122] [123] Furthermore, Siraj-ud-Daula believed that the British East India Company did not receive any permission from the Mughal Emperor Alamgir II to fortify their positions in the territories of the Nawab of Bengal. [124]

On 23 June, Clive received a letter from Mir Jafar asking for a meeting with him. Clive was taken to the Nawab's palace, where he was received by Mir Jafar and his officers. Clive placed Mir Jafar on the throne and acknowledging his position as Nawab, presented him with a plate of gold rupees. [125] [126]

Siraj-ud-daulah had reached Murshidabad at midnight on 23 June. He summoned a council where some advised him to surrender to the British, some to continue the war and some to prolong his flight. At 22:00 on 24 June, Siraj disguised himself and escaped northwards on a boat with his wife and valuable jewels. His intention was to escape to Patna with aid from Jean Law. At midnight on 24 June, Mir Jafar sent several parties in pursuit of Siraj. On 2 July, Siraj reached Rajmahal and took shelter in a deserted garden but was soon discovered and betrayed to the local military governor, the brother of Mir Jafar, by a man who was previously arrested and punished by Siraj. His fate could not be decided by a council headed by Mir Jafar and was handed over to Mir Jafar's son, Miran, who had Siraj murdered that night. His remains were paraded on the streets of Murshidabad the next morning and were buried at the tomb of Alivardi Khan. [113] [127] [128]

According to the treaty drawn between the British and Mir Jafar, the British acquired all the land within the Maratha Ditch and 600 yards (550 m) beyond it and the zamindari of all the land between Calcutta and the sea. Besides confirming the firman of 1717, the treaty also required the restitution of 22,000,000 rupees (£2,750,000) to the British for their losses. However, since the wealth of Siraj-ud-daulah proved to be far less than expected, a council held with the Seths and Rai Durlabh on 29 June decided that one half of the amount was to be paid immediately – two-thirds in coin and one third in jewels and other valuables. [129] [130]

Battle of Bexar

Conflicts with the Afghans

Sikh rebellions

Indian Rebellion of 1857 and Formal End

Conflicts

Meanwhile, some regional polities within the increasingly fragmented Mughal Empire, involved themselves and the state in global conflicts, leading only to defeat and loss of territory during the Carnatic Wars and the Bengal War.

The Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II (1759–1806) made futile attempts to reverse the Mughal decline. Third Battle of Panipat was fought between the Maratha Empire and the Afghans (led by Abdali) in 1761 in which the Afghans were victorious. In 1771, the Marathas recaptured Delhi from Afghan control and in 1784 they officially became the protectors of the emperor in Delhi, [131] a state of affairs that continued until the Second Anglo-Maratha War. Thereafter, the British East India Company became the protectors of the Mughal dynasty in Delhi. [132] The British East India Company took control of the former Mughal province of Bengal-Bihar in 1793 after it abolished local rule (Nizamat) that lasted until 1858, marking the beginning of British colonial era over the Indian subcontinent. By 1857 a considerable part of former Mughal India was under the East India Company's control. After a crushing defeat in the war of 1857–1858 which he nominally led, the last Mughal, Bahadur Shah Zafar, was deposed by the British East India Company and exiled in 1858. Zafar was exiled to Rangoon, Burma. [133] His wife Zeenat Mahal and some of the remaining members of the family accompanied him. At 4 am on 7 October 1858, Zafar along with his wives, and two remaining sons began his journey towards Rangoon in bullock carts escorted by 9th Lancers under the command of Lieutenant Ommaney. [134] Through the Government of India Act 1858 the British Crown assumed direct control of East India Company-held territories in India in the form of the new British Raj. In 1876 the British Queen Victoria assumed the title of Empress of India.

References

- ^ Brown, Katherine Butler (January 2007). "Did Aurangzeb Ban Music? Questions for the Historiography of his Reign". Modern Asian Studies. 41 (1): 79. doi: 10.1017/S0026749X05002313. S2CID 145371208.

- ^ Pletcher, Kenneth, ed. (2010). The History of India. Britannica Educational Publishing. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-61530-201-7.

- ^ Joseph, Paul, ed. (2016). The SAGE Encyclopedia of War: Social Science Perspectives. Sage Publications. pp. 432–433. ISBN 978-1-4833-5988-5.

- ^ Edwardes, Stephen Meredyth; Garrett, Herbert Leonard Offley (1930). Mughal Rule in India. Atlantic Publishers and Distributors. p. 119. ISBN 978-81-7156-551-1.

- ^ Shakir, Moin, ed. (1989). Religion State And Politics in India. Ajanta Publications (India). p. 47. ISBN 978-81-202-0213-9.

- ^ Agrawal (1983), p. 15.

- ^ Berndl, Klaus (2005). National Geographic Visual History of the World. National Geographic Society. pp. 318–320. ISBN 978-0-7922-3695-5.

- ^ Khafi Khan (2006), p. 577.

- ^ Irvine (2006), p. 22.

- ^ Irvine (2006), p. 34.

- ^ Irvine (2006), p. 51.

- ^ Irvine (2006), p. 57.

- ^ a b Irvine (2006), p. 58.

- ^ Irvine (2006), p. 59.

- ^ Irvine (2006), p. 61.

- ^ Irvine (2006), p. 62.

- ^ Irvine (2006), p. 63.

- ^ Faruqui (2012), p. 310 & 315-317.

-

^

A history of modern India, 1480-1950. Claude Markovits, Nisha George, Maggy Hendry. London: Anthem Press. 2002. pp. 174–175.

ISBN

1-84331-004-X.

OCLC

50175836.

{{ cite book}}: CS1 maint: others ( link) - ^ Irvine (2006), p. 282.

- ^ Michael Fischer (2015). A Short History of the Mughal Empire. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 212. ISBN 9780857727770.

- ^ Audrey Truschke (2021). the Language of History:Sanskrit Narratives of Indo-Muslim Rule. Publisher:Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-55195-3. Archived from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

-

^ Muhammad Yasin (1958).

A Social History of Islamic India, 1605–1748. Upper India Publishing House. p. 18.

Archived from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

became virtual rulers and 'de facto' sovereigns when they began to make and unmake emperors. They had developed a sort of common brotherhood among themselves

- ^ Claude Markovits; Maggy Hendry; Nisha George (2002). A History of Modern India, 1480-1950. Anthem. ISBN 9781843310044.

- ^ Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. p. 193. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4.

- ^ Mohammad Yasin. Upper India Publishing House. 1958. p. 18.

-

^ Muzaffar Alam (1986). The Crisis of Empire in Mughal North India. Oxford University Press, Bombay. p. 21.

{{ cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list ( link) - ^ William Irvine (1971). Later Mughal. Atlantic Publishers & Distri. p. 204.

- ^ Calcutta Review Volume 52. Indiana University. 1871. p. 335.

- ^

a

b

c Bhatnagar, V.S. (1974).

Life and times of Sawai Jai Singh. Impex India. pp. 62–63.

The Rajputs broke open the treasury and disbursed its contents among the people.....three thousand enemy soldiers, as Jai Singh wrote to Chattrasal Bundela on October 16, 1708 were killed in the bloody engagement.......The Rajputs had despatched their armies towards Rohtak, Delhi and Agra and had established ouposts at Rewari and Narnaul.

- ^ Rajasthan Through the Ages. Sarup & Sons. 2008-01-01. pp. 100–103. ISBN 9788176258418.

- ^ Pearson (1976), pp. 221–235.

- ^ Vartak (1999), pp. 1126–1134.

- ^ H. S. Sardesai (2002). Shivaji, the great Maratha. Cosmo Publications. pp. 506–. ISBN 978-81-7755-286-7. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- ^ Balkrishna Govind Gokhale (1979). "VII. The Merchant Prince Virji Vora". Surat In The Seventeenth Century. Popular Prakashan. p. 25. ISBN 9788171542208. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- ^ Jacques, Tony (2006). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges. Greenwood Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-313-33536-5. Archived from the original on 2015-06-26. Retrieved 2015-03-27.

- ^ Mehta, Jaswant Lal (2005-01-01). Advanced Study in the History of Modern India 1707-1813. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-932705-54-6.

- ^ a b c d Laine, James W. (2003), "The Hindu Hero: Shivaji and the Saints, 1780–1810", Shivaji: Hindu King in Islamic India, Oxford University Press, pp. 45–47, ISBN 978-019-514126-9

- ^ a b Bang, Peter Fibiger (2021), "Empire—A World History: Anatomy and Concept, Theory and Synthesis", in Bang, Peter Fiber; Bayley, C. A.; Scheidel, Walter (eds.), The Oxford World History of Empire, vol. 1, Oxford University Press, p. 8, ISBN 978-0-19-977236-0

- ^ Mehta (2005), pp. 49–50.

- ^ https://archive.org/stream/rukaatialamgirio00aurarich#page/152/mode/2up%7C Rukaat-i-Alamgiri page 153

-

^

Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Buldhana. Director of Government Printing, Stationery and Publications, Maharashtra State. 1976.

Shahu, the son of Sambhaji along with his mother Yesubai, was made a prisoner

- ^ Richards, J. F. (1981). "Mughal State Finance and the Premodern World Economy". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 23 (2): 285–308. doi: 10.1017/s0010417500013311. JSTOR 178737. S2CID 154809724.

- ^ "Stanley A. Wolpert". UCLA. Archived from the original on 30 September 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ^ Wolpert, Stanley A. (2004) [1977]. New History of India (7th ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 167–168. ISBN 978-0-19-516677-4.

- ^ Haig L, t-Colonel Sir Wolseley (1967). The Cambridge History of India. Volume 3 (III). Turks and Afghans. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University press. p. 395. ISBN 9781343884571. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- ^ a b Sen (2010), p. 12.

- ^ Agrawal (1983), pp. 24, 200–202.

- ^ Mehta (2005), pp. 492–494.

- ^ Montgomery (1972), p. 132.

- ^ Mehta (2005), p. 117.

- ^ Sen (2006), p. 12.

- ^ Sen (2006).

- ^ Sen (2010), p. 23.

- ^ Sen (2010), p. 13.

- ^ Sarkar (1991).

- ^ Roy, Olivier (2011). Holy Ignorance: When Religion and Culture Part Ways. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-80042-6.

- ^ Sen (2010), p. 15.

- ^ Agrawal (1983), p. 26.

- ^ Mehta (2005), p. 274.

- ^ Turchin, Adams & Hall (2006), p. 223.

- ^ Black, Jeremy (2002). Warfare In The Eighteenth Century. Cassell. ISBN 978-0304362127.

- ^ The Great Maratha Mahadji Scindia by N. G. Rathod pp. 8–9

- ^ Poonam Sagar (1993). Maratha Policy Towards Northern India. Meenakshi Prakashan. p. 158.

- ^ Jos J. L. Gommans (1995). The Rise of the Indo-Afghan Empire: c. 1710–1780. Brill. p. 178.

- ^ a b Rathod (1994), p. 8.

- ^ Farooqui (2011), p. 334.

- ^ "Contending with the Ocean", Conflicting Claims to East India Company Wealth, 1600-1650, Amsterdam University Press, pp. 137–170, 2024-02-08, doi: 10.2307/jj.11930968.7, ISBN 978-90-485-5785-1, retrieved 2024-04-06

- ^ a b Naravane (2014), p. 92.

- ^ "Nadir Shah". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Ghafouri (2008), p. 383.

- ^ G. S. Cheema (2002). The Forgotten Mughals: A History of the Later Emperors of the House of Babar, 1707–1857. Manohar Publishers & Distributors. p. 195. ISBN 9788173044168.

- ^ Moghtader, Gholam-Hussein (2008). The Great Battles of Nader Shah. Donyaye Ketab.

- ^ "India vii. Relations: The Afsharid and Zand – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- ^ Satish Chandra (1959). Parties And Politics At The Mughal Court. Oxford University Press. p. 245.

-

^ Sir Jadunath Sarkar (1920).

The Mughal Administration. Superintendent, Government Printing, Bihar and Orissa. p. 17.

musketeers were mostly recruited from certain Hindu tribes , such as the Bundelas , the Karnatakis , and the men of Buxar

-

^ Ghosh, D. K. Ed. (1978).

A Comprehensive History Of India Vol. 9. Orient Longmans.

The Indian muslims looked down upon fighting with muskets and prided on sword play. The best gunners in the mughal army were hindus

- ^ William Irvine (2007). Later Muguhals. Sang-e-Meel Publications. p. 668.

- ^ J.J.L. Gommans (2022). Mughal Warfare: Indian Frontiers and Highroads to Empire 1500–1700. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781134552764.

- ^ "History of Nadir Shah's Wars" (Taarikhe Jahangoshaaye Naaderi), 1759, Mirza Mehdi Khan Esterabadi, (Court Historian).

- ^ Moghtader, Gholam-Hussein(2008). The Great Batlles of Nader Shah. Donyaye Ketab.

- ^ Michael Axworthy (2010). Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 202. ISBN 9780857724168.

- ^ Axworthy p. 8.

- ^ "An Outline of the History of Persia During the Last Two Centuries (A.D. 1722–1922)". Edward G. Browne. London: Packard Humanities Institute. p. 33. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- ^ Axworthy, Michael, Iran: Empire of the Mind, Penguin Books, 2007. p. 159. [ ISBN missing]

- ^ Cust, Edward, Annals of the wars of the eighteenth century, (Gilbert & Rivington Printers: London, 1862), 228.

- ^ Hari Ram Gupta (1999). History of the Sikhs: Evolution of Sikh confederacies, 1708–69. Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 54. ISBN 9788121502481.

- ^ Vidya Dhar Mahajan (2020). Modern Indian History. S. Chand Limited. p. 57. ISBN 9789352836192.

- ^ Paul Joseph (2016). The Sage Encyclopedia of War: Social Science Perspectives. Sage Publications. ISBN 9781483359908.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi (1999). Revenge and Reconciliation: Understanding South Asian History. Penguin Books. pp. 117–118. ISBN 9780140290455.

- ^ Brigadier-General Sykes, Sir Percy (1930). "A history of Persia, Vol. II", third edition, p. 260. Macmillan & Co.

- ^ "La stratégie militaire, les campagneset les batailles de Nâder Shâh – La Revue de Téhéran – Iran". teheran.ir. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ^ Axworthy (2009)

- ^ Axworthy (2006), pp. 212, 216.

- ^ Hasan, Farhat (1991). "Conflict and Cooperation in Anglo-Mughal Trade Relations during the Reign of Aurangzeb". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 34 (4): 351–360. doi: 10.1163/156852091X00058. JSTOR 3632456.

- ^ "Asia Facts, information, pictures | Encyclopedia.com articles about Asia | Europe, 1450 to 1789: Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World". encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2015-02-23.

- ^ John Keay, India: A History, pp. 79–81, ISBN 9780802195500

- ^ The Evolution of Judicial Systems and Law in the Sub-continent by Ayub Premi, page 42, University of California

- ^ Bandyopādhyāẏa, Śekhara (2004). From Plassey to Partition. p. 39. ISBN 81-250-2596-0 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b James Talboys Wheeler. India under British Rule. pp. 19–22.

- ^ Ward; Prothero (1908). The Cambridge Modern History. Vol. 5. Macmillan, University of Michigan. p. 699.

- ^ Jaswant Lal Mehta (January 2005). Advanced Study in the History of Modern India 1707–1813. pp. 16–18. ISBN 9781932705546.

- ^ Chakrabarty, Phanindranath (1983). Anglo-Mughal Commercial Relations, 1583–1717. O.P.S. Publishers, University of California. p. 257.

- ^ "Asia Facts, information, pictures | Encyclopedia.com articles about Asia | Europe, 1450 to 1789: Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World". encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2015-02-23.

- ^ Keay, John. India: A History. New York: HarperCollins. p. 372.

- ^ Kohli, Atul (31 January 2020). Imperialism and the Developing World: How Britain and the United States Shaped the Global Periphery. Oxford University Press. pp. 42–44.

- ^ Erikson, Emily (13 September 2016). Between Monopoly and Free Trade: The English East India Company, 1600–1757. Princeton University Press. p. 193. ISBN 9780691173795.

- ^ a b c d e Naravane (2014), pp. 150–159.

- ^ Dodwell, H. H. (ed), Cambridge History of India, Vol. v.

- ^ Harvey (1998), p. 42

- ^ Campbell & Watts (1760), [1].

- ^ Robins, Nick. "This Imperious Company – The East India Company and the Modern Multinational – Nick Robins – Gresham College Lectures". Gresham College Lectures. Gresham College. Archived from the original on 19 June 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ a b Harrington (1994), p. 84.

- ^ Robins, Nick. "This Imperious Company – The East India Company and the Modern Multinational – Nick Robins – Gresham College Lectures". Gresham College Lectures. Gresham College. Archived from the original on 19 June 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ Naravane (2014), p. 38.

- ^ Hill (1905), pp. cxxxix–cxl.

- ^ Hill (1905), pp. cxliv.

- ^ Orme, pp. 126–128

- ^ Harrington (1994), p. 24.

- ^ Malleson, p. 46

- ^ Stanhope (1853), p. 334.

- ^ Hill (1905), pp. cxlvi–cxlvii.

- ^ Orme, pp. 131–136

- ^ Rai, R. History. FK Publications. p. 44. ISBN 978-8187139690. Retrieved 13 September 2015.[ permanent dead link]

- ^ Harrington (1994), pp. 83–84.

- ^ Orme, pp. 178–81

- ^ Orme, pp. 183–84

- ^ Stanhope (1853), pp. 346–347.

- ^ Orme, pp. 180–82

- ^ Stanhope (1853), pp. 347–348.

- ^ Rathod, N.G. (1994). The Great Maratha Mahadaji Scindia. New Delhi: Sarup & Sons. p. 8. ISBN 978-81-85431-52-9.

- ^ Bose, Sugata; Jalal, Ayesha (2004). Modern South Asia: History, Culture, Political Economy (2nd ed.). Routledge. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-203-71253-5.

- ^ Conermann, Stephan (2015-08-04), "Mughal Empire", Encyclopedia of Early Modern History Online, Brill, doi: 10.1163/2352-0272_emho_com_024206, archived from the original on 26 March 2022, retrieved 2022-03-28

- ^ Dalrymple, William (2007). The Last Mughal. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-310243-4.

Bibliography

- Agrawal, Ashvini (1983). Studies in Mughal History. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-2326-5.

-

Axworthy, Michael (2006). The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant. I.B.Tauris.

ISBN

978-1850437062.

- Axworthy, Michael (2009). The Sword of Persia; Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant. I B Tauris.

- Campbell, John; Watts, William (1760), "Memoirs of the Revolution in Bengal, Anno Domini 1757", World Digital Library, retrieved 30 September 2013

- Farooqui, Salma Ahmed (2011). A Comprehensive History of Medieval India: Twelfth to the Mid-Eighteenth Century. Pearson Education India. ISBN 978-81-317-3202-1.

- Faruqui, Munis D (2012), Princes of the Mughal Empire, 1504-1719, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-139-52619-7, OCLC 808366461

- Ghafouri, Ali (2008). History of Iran's wars: from the Medes to now. Etela'at Publishing.

- Harrington, Peter (1994), Plassey 1757, Clive of India's Finest Hour; Osprey Campaign Series #36, London: Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-85532-352-4

- Hill, S.C., ed. (1905), Bengal in 1756–1757, Indian Records, vol. 1, London: John Murray, ISBN 1-148-92557-0, OCLC 469357208

- Irvine, William (2006). The Later Mughals. Low Price Publications. ISBN 81-7536-406-8. [First published 1921]

- Jackson, William Joseph (2005). Vijayanagara voices: exploring South Indian history and Hindu literature. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7546-3950-3.

- Khafi Khan, Muhammad (2006). Elliot, H.M.; Dowson, John (eds.). Muntakhab-ul Lubab. Sang-e-Meel. ISBN 969-35-1882-9. [Translation first published 1877]

- Malleson, George B. (1885), The Decisive Battles of India from 1746 to 1819, London: W.H. Allen, ISBN 0-554-47620-7, OCLC 3680884

- Montgomery, Bernard Law (1972). A Concise History of Warfare. Collins. ISBN 9780001921498.

- Naravane, M.S. (2014). Battles of the Honorourable East India Company. A.P.H. Publishing Corporation. ISBN 9788131300343.

- Orme, Robert (1861), A History of the Military Transactions of the British Nation in Indostan from the year MDCCXLV, vol. II, Madras: Athenaeum Press, OCLC 46390406

- Pearson, M. N. (February 1976). "Shivaji and the Decline of the Mughal Empire". The Journal of Asian Studies. 35 (2): 221–235. doi: 10.2307/2053980. JSTOR 2053980. S2CID 162482005.

- Sarkar, Jadunath (1991). Fall of the Mughal Empire. Vol. I (4th ed.). Orient Longman. ISBN 978-81-250-1149-1.

- Sen, S.N (2006). History Modern India (3rd ed.). The New Age. ISBN 978-81-224-1774-6.

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (2010). An Advanced History of Modern India. Macmillan India. pp. 1941–. ISBN 978-0-230-32885-3.

- Stanhope, Philip H. (1853), History of England from the Peace of Utrecht to the Peace of Versailles (1713–1783), vol. IV, Leipzig: Bernhard Tauchnitz, ISBN 1-4069-8152-4, OCLC 80350373

- Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D. (2006). "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires and Modern States". Journal of World-Systems Research. 12 (2): 219–229. doi: 10.5195/JWSR.2006.369. ISSN 1076-156X.

- Vartak, Malavika (8–14 May 1999). "Shivaji Maharaj: Growth of a Symbol". Economic and Political Weekly. 34 (19): 1126–1134. JSTOR 4407933.