Commerce, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

Looking west from Commerce | |

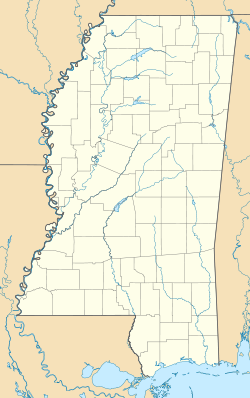

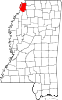

| Coordinates: 34°49′10″N 90°22′49″W / 34.81944°N 90.38028°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Mississippi |

| County | Tunica |

| Elevation | 200 ft (61 m) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 ( Central (CST)) |

| • Summer ( DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| GNIS feature ID | 668724 [1] |

Commerce is a ghost town in Tunica County, Mississippi, United States. Commerce Landing was the town's port.

Commerce is located on the Mississippi River, 4 mi (6.4 km) west of Tunica Resorts.

Once a thriving river port, Commerce today is farmland surrounded by large casinos. Little remains of the original community.

History

Commerce Landing is one of two hypothesized locations where Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto may have crossed the Mississippi River (the other is Friars Point, Mississippi). Archeological sites at Commerce have dated to around 1541, and three archeological sites near Commerce have been found to contain Late Mississippian ceramics, which corresponds to records left by the Spanish describing three Quizquiz Indian villages they encountered near the Mississippi River. [2]

During the 1820s, both Commerce and Mound City, Arkansas were considered commercial rivals of Memphis, Tennessee, and by 1839, Commerce had a larger population than Memphis (located 40 mi (64 km) north on the Mississippi River). [3]

Thomas Fletcher, an early settler, along with an unknown Choctaw Indian, named the place "Commerce", expecting it to become a great city. Commerce was founded in 1834, and became the county seat in 1836. It incorporated in 1839, and was the first town in Tunica County. [4]

There is a story about artist John Banvard stopping at Commerce as he traveled the Mississippi River with a floating exhibition of his paintings during the 1840s. When a local "official" in Commerce attempted to extort a docking fee, Banvard's crew floated downstream with the man still on board.

They set him ashore in a thick cane-break, on the opposite side of the river, about three miles below the town. How he got home that night is best known to himself. We venture to say he never meddled with business that did not concern him after passing that night among the musquitoes and alligators. [5]

The construction of a railroad through Commerce was nearly completed in 1840, when the administration of Governor Alexander McNutt took the charter away from the Hernando Bank, bankrupting both the bank and the railroad. [4]

In 1843, the Mississippi River changed its course, submerging a portion of Commerce Landing. In an effort to save their homes, the early settlers built the first levees in this portion of the Delta. The county seat was temporarily moved to Peyton. Six months later it was moved back to Commerce. [6] [7] The Board of Supervisors then moved the county seat to Austin. [4] [8]

Explorer and naturalist Samuel Washington Woodhouse documented stopping above Commerce in 1849 "to take in wood". [9]

Much of the land of Commerce was sold by Thomas Fletcher to Ransom H. Byrn, who planted cotton, and was by 1860 the second largest slave owner in Tunica County. [10]

In 1888, the steamer Kate Adams, the fastest boat of its type on the Mississippi River, caught fire near Commerce, killing 23. The people of Commerce provided food, clothing and transportation to the survivors. [11]

As a child during the 1920s, blues musician Robert Johnson lived with his parents on the Abbay & Leatherman plantation in Commerce, and attended nearby Indian Creek School. A Mississippi Blues Trail marker is located in Commerce. [12] [13]

In 1955, a tornado touched down on the Abbay & Leatherman plantation, killing 28. It cut a 200 ft (61 m) wide path and destroyed a row of tenant houses, a school, a church, and a cotton gin. The school was in session, and most of the dead were children and their teacher. [14]

References

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Commerce, Mississippi

- ^ Morse, Dan F. (1983). "Archeology of the Central Mississippi Valley" (PDF). Academic Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- ^ Biles, Roger (1986). Memphis in the Great Depression. University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 9781572331570.

- ^ a b c "Communities of Tunica County, Mississippi". MSGenWeb. Retrieved September 9, 2013.

- ^ Howitt, Mary Botham (1848). Howitt's Journal of Literature and Popular Progress, Volume 3. William Lovett.

- ^ "Museum History". Tunica Museum. Retrieved December 1, 2013.

- ^ "Tunica Timeline". Tunica Convention and Visitors Bureau. Archived from the original on 2014-02-07. Retrieved December 1, 2013.

- ^ McElvaine, Robert S. (1988). Mississippi: The WPA Guide to the Magnolia State. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781604732894.

- ^ Woodhouse, S.W. (1992). A Naturalist in Indian Territory: The Journals of S. W. Woodhouse, 1849-1850. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806128054.

- ^ Blake, Tom (Feb 2002). "Tunica County: Largest Slaveholders from 1860 Slave Census Schedules". Rootsweb.

- ^ "Twenty-Three Lives Lost" (PDF). New York Times. Dec 24, 1888.

- ^ "Abbay & Leatherman". Mississippi Blues Foundation. Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- ^ Gates, Henry Louis (2004). African American Lives. Oxford. ISBN 9780199882861.

- ^ "Commerce, Olive Branch, MS Tornado Damages Small Towns, Feb 1955". Dixon Evening Telegraph. Feb 2, 1955. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved September 11, 2013.

External links

- Map from 1842 showing the location of Commerce in Mississippi

- Photo of Commerce Landing in 2011

- Video of Abbay & Leatherman Plantation