| Cardiomyopathy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Opened left ventricle showing thickening, dilatation, and subendocardial fibrosis noticeable as increased whiteness of the inside of the heart. | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

| Symptoms | |

| Complications | |

| Types | |

| Causes |

|

| Treatment | Depends on type and symptoms [5] |

| Frequency | 2.5 million with myocarditis (2015) [6] |

| Deaths | 354,000 with myocarditis (2015) [7] |

Cardiomyopathy is a group of primary diseases of the heart muscle. [1] Early on there may be few or no symptoms. [1] As the disease worsens, shortness of breath, feeling tired, and swelling of the legs may occur, due to the onset of heart failure. [1] An irregular heart beat and fainting may occur. [1] Those affected are at an increased risk of sudden cardiac death. [2]

As of 2013, cardiomyopathies are defined as "disorders characterized by morphologically and functionally abnormal myocardium in the absence of any other disease that is sufficient, by itself, to cause the observed phenotype." [8] [9] Types of cardiomyopathy include hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, dilated cardiomyopathy, restrictive cardiomyopathy, arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia, and Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (broken heart syndrome). [3] In hypertrophic cardiomyopathy the heart muscle enlarges and thickens. [3] In dilated cardiomyopathy the ventricles enlarge and weaken. [3] In restrictive cardiomyopathy the ventricle stiffens. [3]

In many cases, the cause cannot be determined. [4] Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is usually inherited, whereas dilated cardiomyopathy is inherited in about one third of cases. [4] Dilated cardiomyopathy may also result from alcohol, heavy metals, coronary artery disease, cocaine use, and viral infections. [4] Restrictive cardiomyopathy may be caused by amyloidosis, hemochromatosis, and some cancer treatments. [4] Broken heart syndrome is caused by extreme emotional or physical stress. [3]

Treatment depends on the type of cardiomyopathy and the severity of symptoms. [5] Treatments may include lifestyle changes, medications, or surgery. [5] Surgery may include a ventricular assist device or heart transplant. [5] In 2015 cardiomyopathy and myocarditis affected 2.5 million people. [6] Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy affects about 1 in 500 people while dilated cardiomyopathy affects 1 in 2,500. [3] [10] They resulted in 354,000 deaths up from 294,000 in 1990. [7] [11] Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia is more common in young people. [2]

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of cardiomyopathy include:

- Shortness of breath or trouble breathing, especially with physical exertion

- Fatigue

- Swelling in the ankles, feet, legs, abdomen and veins in the neck

- Dizziness

- Lightheadedness

- Fainting during physical activity

- Arrhythmias (abnormal heartbeats)

- Chest pain, especially after physical exertion or heavy meals

- Heart murmurs (unusual sounds associated with heartbeats)

Causes

Cardiomyopathies can be of genetic (familial) or non-genetic (acquired) origin. [12] Genetic cardiomyopathies usually are caused by sarcomere or cytoskeletal diseases, neuromuscular disorders, inborn errors of metabolism, malformation syndromes and sometimes are unidentified. [13] [14] Non-genetic cardiomyopathies can have definitive causes such as viral infections, myocarditis and others. [15] [16]

Cardiomyopathies are either confined to the heart or are part of a generalized systemic disorder, both often leading to cardiovascular death or progressive heart failure-related disability. Other diseases that cause heart muscle dysfunction are excluded, such as coronary artery disease, hypertension, or abnormalities of the heart valves. [17] Often, the underlying cause remains unknown, but in many cases the cause may be identifiable. [18] Alcoholism, for example, has been identified as a cause of dilated cardiomyopathy, as has drug toxicity, and certain infections (including Hepatitis C). [19] [20] [21] Untreated celiac disease can cause cardiomyopathies, which can completely reverse with a timely diagnosis. [22] In addition to acquired causes, molecular biology and genetics have given rise to the recognition of various genetic causes. [20] [23]

A more clinical categorization of cardiomyopathy as 'hypertrophied', 'dilated', or 'restrictive', [24] has become difficult to maintain because some of the conditions could fulfill more than one of those three categories at any particular stage of their development. [25]

The current American Heart Association (AHA) definition divides cardiomyopathies into primary, which affect the heart alone, and secondary, which are the result of illness affecting other parts of the body. These categories are further broken down into subgroups which incorporate new genetic and molecular biology knowledge. [26]

Mechanism

The pathophysiology of cardiomyopathies is better understood at the cellular level with advances in molecular techniques. Mutant proteins can disturb cardiac function in the contractile apparatus (or mechanosensitive complexes). Cardiomyocyte alterations and their persistent responses at the cellular level cause changes that are correlated with sudden cardiac death and other cardiac problems. [27]

Cardiomyopathies are generally varied individually. Different factors can cause Cardiomyopathies in adults as well as children. To exemplify, Dilated Cardiomyopathy in adults is associated with Ischemic Cardiomyopathy, Hypertension, Valvular diseases, and Genetics. While in Children, Neuromuscular diseases such as Becker muscular dystrophy, including X-linked genetic disorder, are directly linked with their Cardiomyopathies. [28]

Diagnosis

Among the diagnostic procedures done to determine a cardiomyopathy are: [29]

- Physical exam

- Family history

- Blood test

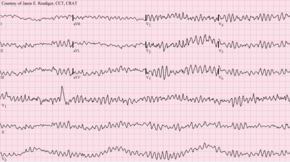

- ECG

- Echocardiogram

- Stress test

- Genetic testing

Classification

Cardiomyopathies can be classified using different criteria: [30]

- Primary/intrinsic cardiomyopathies

[31]

- Congenital

- Mixed

- Acquired

- Stress cardiomyopathy

- Myocarditis, inflammation of and injury to heart tissue due in part to its infiltration by lymphocytes and monocytes [32] [33]

- Eosinophilic myocarditis, inflammation of and injury to heart tissue due in part to its infiltration by eosinophils [32]

- Ischemic cardiomyopathy (not formally included in the classification, due to ischemic cardiomyopathy being a direct result of another cardiac problem) [31]

- Secondary/extrinsic cardiomyopathies

[31]

- Metabolic/storage

- Fabry's disease

- Hemochromatosis

- Endomyocardial

- Endocrine

- Cardiofacial

- Neuromuscular

- Other

- Obesity-associated cardiomyopathy [34]

- Metabolic/storage

Treatment

Treatment may include suggestion of lifestyle changes to better manage the condition. Treatment depends on the type of cardiomyopathy and condition of disease, but may include medication (conservative treatment) or iatrogenic/implanted pacemakers for slow heart rates, defibrillators for those prone to fatal heart rhythms, ventricular assist devices (VADs) for severe heart failure, or catheter ablation for recurring dysrhythmias that cannot be eliminated by medication or mechanical cardioversion. The goal of treatment is often symptom relief, and some patients may eventually require a heart transplant. [29]

See also

- Myopathy

- Fibrosing cardiomyopathy (disease in great apes)

- Basic Research in Cardiology

References

- ^ a b c d e f "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Cardiomyopathy?". NHLBI. 22 June 2016. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ a b c "Who Is at Risk for Cardiomyopathy?". NHLBI. 22 June 2016. Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Types of Cardiomyopathy". NHLBI. 22 June 2016. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "What Causes Cardiomyopathy?". NHLBI. 22 June 2016. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ a b c d "How Is Cardiomyopathy Treated?". NHLBI. 22 June 2016. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ a b GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ a b GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ Harrison's principles of internal medicine (21st ed.). New York: McGraw Hill. 2022. p. 1954. ISBN 978-1-264-26850-4.

- ^ Arbustini E, Narula N, Dec GW, Reddy KS, Greenberg B, Kushwaha S, Marwick T, Pinney S, Bellazzi R, Favalli V, Kramer C, Roberts R, Zoghbi WA, Bonow R, Tavazzi L (3 December 2013). "The MOGE(S) Classification for a Phenotype–Genotype Nomenclature of Cardiomyopathy". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 62 (22): 2046–2072. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.08.1644. PMID 24263073. S2CID 43240625.

- ^ Practical Cardiovascular Pathology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2010. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-60547-841-8. Archived from the original on 14 September 2016.

- ^ GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ^ Bakalakos A, Ritsatos K, Anastasakis A (1 September 2018). "Current perspectives on the diagnosis and management of dilated cardiomyopathy Beyond heart failure: a Cardiomyopathy Clinic Doctor's point of view". Hellenic Journal of Cardiology. 59 (5): 254–261. doi: 10.1016/j.hjc.2018.05.008. ISSN 1109-9666. PMID 29807197. S2CID 44146977.

- ^ Rath A, Weintraub R (23 July 2021). "Overview of Cardiomyopathies in Childhood". Frontiers in Pediatrics. 9: 708732. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.708732. ISSN 2296-2360. PMC 8342800. PMID 34368032.

- ^ Gorla S, Raja K, Garg A, Barbouth D, Rusconi P (December 2018). "Infantile Onset Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Secondary to PRKAG2 Gene Mutation is Associated with Poor Prognosis". Journal of Pediatric Genetics. 07 (4): 180–184. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1657763. ISSN 2146-4596. PMC 6234042. PMID 30430036.

- ^ Law ML, Cohen H, Martin AA, Angulski AB, Metzger JM (February 2020). "Dysregulation of Calcium Handling in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy-Associated Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Mechanisms and Experimental Therapeutic Strategies". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 9 (2): 520. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020520. ISSN 2077-0383. PMC 7074327. PMID 32075145.

- ^ Cimiotti D, Budde H, Hassoun R, Jaquet K (8 January 2021). "Genetic Restrictive Cardiomyopathy: Causes and Consequences—An Integrative Approach". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 22 (2): 558. doi: 10.3390/ijms22020558. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 7827163. PMID 33429969.

- ^ Lakdawala NK, Stevenson LW, Loscalzo J (2015). "Chapter 287". In Kasper DL, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J (eds.). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (19th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 1553. ISBN 978-0-07-180215-4.

- ^ Lilly, Leonard S., ed. (2011). Pathophysiology of heart disease: a collaborative project of medical students and faculty (5th ed.). Baltimore, MD: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1-60547-723-7. OCLC 649701807.

- ^ Adam A, Nicholson C, Owens L (2008). "Alcoholic dilated cardiomyopathy". Nurs Stand (Review). 22 (38): 42–7. doi: 10.7748/ns2008.05.22.38.42.c6565. PMID 18578120.

- ^ a b Westphal JG, Rigopoulos AG, Bakogiannis C, Ludwig SE, Mavrogeni S, Bigalke B, et al. (2017). "The MOGE(S) classification for cardiomyopathies: current status and future outlook". Heart Fail Rev (Review). 22 (6): 743–752. doi: 10.1007/s10741-017-9641-4. PMID 28721466. S2CID 36117047.

- ^ Domont F, Cacoub P (2016). "Chronic hepatitis C virus infection, a new cardiovascular risk factor?". Liver Int (Review). 36 (5): 621–7. doi: 10.1111/liv.13064. PMID 26763484.

- ^ Ciaccio EJ, Lewis SK, Biviano AB, Iyer V, Garan H, Green PH (2017). "Cardiovascular involvement in celiac disease". World J Cardiol (Review). 9 (8): 652–666. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v9.i8.652. PMC 5583538. PMID 28932354.

- ^ Simpson S, Rutland P, Rutland CS (2017). "Genomic Insights into Cardiomyopathies: A Comparative Cross-Species Review". Vet Sci (Review). 4 (1): 19. doi: 10.3390/vetsci4010019. PMC 5606618. PMID 29056678.

- ^ Valentin Fuster, John Willis Hurst (2004). Hurst's the heart. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 1884. ISBN 978-0-07-143225-2. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ Llamas-Esperón GA, Llamas-Delgado G (2022). "Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Proposal for a new classification". Arch Cardiol Mex. 92 (3): 377–389. doi: 10.24875/ACM.21000301. PMC 9262289. PMID 35772124.

- ^ McCartan C, Maso R, Jayasinghe SR, Griffiths LR (2012). "Cardiomyopathy Classification: Ongoing Debate in the Genomics Era". Biochem Res Int. 2012: 796926. doi: 10.1155/2012/796926. PMC 3423823. PMID 22924131.

- ^ Harvey PA, Leinwand LA (8 August 2011). "Cellular mechanisms of cardiomyopathy". The Journal of Cell Biology. 194 (3): 355–365. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201101100. ISSN 0021-9525. PMC 3153638. PMID 21825071.

- ^ Braunwald E (15 September 2017). "Cardiomyopathies: An Overview". Circulation Research. 121 (7): 711–721. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311812. ISSN 1524-4571. PMID 28912178. S2CID 36384619.

- ^ a b "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Cardiomyopathy? - NHLBI, NIH". nhlbi.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ^ Vinay K (2013). Robbins Basic Pathology. Elsevier. p. 396. ISBN 978-1-4377-1781-5.

- ^ a b c Maron BJ, Towbin JA, Thiene G, Antzelevitch C, Corrado D, Arnett D, Moss AJ, Seidman CE, Young JB (11 April 2006). "Contemporary Definitions and Classification of the Cardiomyopathies". Circulation. 113 (14): 1807–1816. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174287. ISSN 0009-7322. PMID 16567565. S2CID 6660623. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ a b Séguéla PE, Iriart X, Acar P, Montaudon M, Roudaut R, Thambo JB (2015). "Eosinophilic cardiac disease: Molecular, clinical and imaging aspects". Archives of Cardiovascular Diseases. 108 (4): 258–68. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2015.01.006. PMID 25858537.

- ^ Rose NR (2016). "Viral myocarditis". Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 28 (4): 383–9. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000303. PMC 4948180. PMID 27166925.

- ^ Lipshultz SE, Messiah SE, Miller TL (5 April 2012). Pediatric Metabolic Syndrome: Comprehensive Clinical Review and Related Health Issues. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 200. ISBN 978-1-4471-2365-1. Archived from the original on 29 May 2016.

Further reading

- Boudina S, Abel ED (1 March 2010). "Diabetic cardiomyopathy, causes and effects". Reviews in Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders. 11 (1): 31–39. doi: 10.1007/s11154-010-9131-7. ISSN 1389-9155. PMC 2914514. PMID 20180026.

- Marian AJ, Roberts R (1 April 2001). "The Molecular Genetic Basis for Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy". Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 33 (4): 655–670. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1340. ISSN 0022-2828. PMC 2901497. PMID 11273720.

- Acton QA (2013). Advances in Heart Research and Application: 2013 Edition. Scholarly Editions. ISBN 978-1-4816-8280-0.

- Towbin JA (2014). "Inherited cardiomyopathies". Circulation Journal. 78 (10): 2347–56. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-14-0893. ISSN 1347-4820. PMC 4467885. PMID 25186923.

- Maron BJ, Udelson JE, Bonow RO, Nishimura RA, Ackerman MJ, Estes NA, Cooper LT, Link MS, Maron MS (1 December 2015). "Eligibility and Disqualification Recommendations for Competitive Athletes With Cardiovascular Abnormalities: Task Force 3: Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy, Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy and Other Cardiomyopathies, and Myocarditis: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology". Circulation. 132 (22): e273–280. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000239. ISSN 1524-4539. PMID 26621644. S2CID 207639288.