| Campaigns of the South | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Colombian War of Independence and Spanish American Wars of independence | |||||||||

Greater Colombia in 1821 Territory annexed to

Greater Colombia

Peru, consolidation of its independence in 1824.

Bolivia, consolidation of its independence in 1825, without military action. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Pro-independence forces

Co-belligerents With support from |

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 30,000 soldiers | 24,000 soldiers (4000 soldiers in Quito and 20,000 soldiers in Peru) | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 24,000 casualties | 21,000 casualties | ||||||||

Campaigns of the South (1820—1826; Spanish: Campañas del Sur) is the name given to a series of military campaigns that Greater Colombia launched between 1820 and 1826 in South America with the purpose of expanding over the territories of the current republics of Colombia and Ecuador, as well as consolidating the independence of the republics of Peru and Bolivia. This was an extension of the multifaceted civil war launched against the Royalist Army in the Americas, which sustained the integrity of the Spanish Empire in such territories. Beyond the surrender of the regular armies, the royalist guerrillas in each country fought for several more years.

Determining which battles are included in the campaigns of the South varies so widely that some historians refer by this name to the liberation campaigns of Quito and Pasto between 1820 and 1822, while others refer to military operations between 1821 and 1826, when the fortress of El Callao surrendered. However, it can be said for certain that the goal of the campaigns of the South was to end the Spanish American wars of independence in South America and, as an additional result, the boom of the influence and power of Greater Colombia. The latter, under the presidency of Simón Bolívar, sought to bring together the new states under its hegemony. However, this project failed and Greater Colombia itself disappeared in 1831, balkanized for the secession of the states that conformed it.

Quito Campaign

Sucre’s Operations in Ecuador

After the revolution on 9 October 1820, the city of Guayaquil had been constituted as an independent state, the Free Province of Guayaquil. However, it soon found itself in a delicate military situation after the people of Guayaquil were defeated at the First Battle of Huachi and the Battle of Tanizagua. José Joaquín de Olmedo requested military aid from Greater Colombia to defend the city and to liberate the Royal Audience of Quito. Early in 1821, Bolívar sent his best general, Antonio José de Sucre, to Guayaquil to replace General José Mires. Sucre arrived on 6 May 1821 with around 650 Colombian soldiers, who were joined by around 1,400 Ecuadorians. [1] Sucre’s instructions consisted of taking command of the troops that were in Guayaquil, securing the incorporation of the province into Colombia, and working with the Liberator to prepare the operations to liberate Quito. [2] Quito was strongly guarded despite the fact that the Royalist troops had decreased by half in recent years, from 4,000 to 2,000. [3] [4] [5]

The forces that garrisoned Guayaquil in 1820 included 1,500 defenders: by order of José Fernando de Abascal, 250–300 sailors operating seven gunboats (the port was the main arsenal and shipyard in the Spanish Pacific), [6] 600 infantry soldiers of the Granaderos de Reserva battalion [7] originally from Cuzco, [8] 200 volunteers [9] of half [10] the Milicias Battalion from Guayaquil, 150 cavalry soldiers of the Caballería de Daule squadron, and 200 gunners of the Artillery brigade. The city had a population of 14,000 people and controlled a province of 71,000 souls, of whom 12,000 were Europeans. In total, the Royal Audience of Quito had 3,500 soldiers under the command of Marshal Melchior Aymerich.

Upon Sucre’s arrival in Guayaquil, he started to organize and train the troops. [11] On March 15, he signed an agreement with the city’s Government Junta, which stipulated that the Province of Guayaquil would remain under the protection and custody of Colombia, thus annulling the treaty signed with the Peruvian agents. Sucre placed his troops in Samborondón and Babahoyo to block the entrance of the royalists to the province. On 17 July of that year, an anti-Colombian and pro-royalist rebellion took place, which was successfully squashed.

Upon learning of the rebellion, the royalists prepared to support it. Meanwhile, Governor Aymerich marched south with 2,000 men, while Colonel González marched from Cuenca to Guayaquil threatening the communications sent by Sucre, who was on his way to fight Aymerich. When Sucre learned of the movement, he retreated to confront González, defeating him on 12 August in the Battle of Yaguachi. Afterwards, Sucre returned to the north to confront Aymerich, but the latter retreated to the north. The army pursued the royalists for a long stretch but the political situation in Guayaquil forced Sucre to return.

After the political situation in the city had calmed down, Sucre headed back to the mountains with 900 infantry soldiers and 70 cavalry soldiers, in search of Aymerich. For several days, he maneuvered against him, crossed the Chimborazo, and arrived on 11 September at the Upper Valley of the Ambato River. Sucre was reluctant to descend from the mountain range due to the numerical advantage of the Spanish cavalry but, harassed by his companions, he descended on the 12th to Santa Rosa, occupying defensive positions while Aymerich advanced towards Ambato. Both armies faced each other in the Second Battle of Huachi. Sucre set up a solid defensive formation but when the royalists attacked, General Mires got ahead of the counter-offensive and, after his attack was resisted, the patriot army was surrounded, defeated, and almost destroyed.

Back in Guayaquil, Sucre urgently needed reinforcements to recover from the defeat of Huachi, for which he asked Francisco de Paula Santander to send troops, but the latter chose instead to reinforce the division of Pedro León Torres, who had to go overland via Popayán- Pasto- Quito. In such circumstances, Sucre wrote a letter to the Protector of Peru, José de San Martín, to ask for the Numancia Battalion, a unit formed in Venezuela in 1813 and sent by Pablo Morillo to Peru three years later. In 1820, it had gone over to the Protector’s forces and wished to return home. San Martín did not want to give up the Numancia, which was the best battalion at his disposal. Therefore, he sent some forces in its place under the command of Colonel Andrés de Santa Cruz. Santa Cruz’s division was reorganized into battalions No. 2 and 4 or Piura, the Cazadores del Perú and Granaderos de los Andes squadrons, and an artillery picket, accounting for 1,622 [12] to 1,693 [13] troops.

With Santa Cruz’s forces and the imposed impressment, Sucre once again had about 1,200 troops though most did not have any military experience except for the Trujillo battalion, with some training, and the Mounted Grenadiers squadron of 90 veterans under the command of Lavalle.

Sucre decided to resume the campaign from the south of Guayaquil, for which he sent small detachments in various directions in order to mislead the royalists about the route their offensive would take while he embarked with the army in Guayaquil and headed by sea to Machala. After disembarking his troops, he headed to Saguro, where he met with the Peruvians of Santa Cruz. Afterwards, he headed to Cuenca, arriving there on 23 February 1822. He waited there for the date agreed by Bolívar to start the offensive. Meanwhile, he increased his forces with some reinforcements that had arrived from Guayaquil.

Once Bolívar’s authorization had arrived, Sucre advanced towards Alausí at the beginning of April. He now had about 2,000 infantry troops and 400 cavalry troops at his disposal. The royalist forces were about 2,000 regular soldiers, plus hundreds of conscripts. By mid-month, the republicans numbered 3,000 men under Sucre's command in various garrisons, including Chileans and Argentinians in the mounted units. [14] On the 20th of that same month, they were ambushed by the Spaniards but these were repulsed. The following day, they found that the royalists had fortified the road so Sucre flanked the position and offered battle, but the Spaniards preferred to retreat. Sucre ordered Colonel Diego Ibarra to attack with his cavalry the royalists who were retreating from the village of Riobamba. In turn, the Spaniards sent their cavalry to protect their retreat.

The army left Riobamba on 28 April headed to the city of Latacunga, where they arrived on 2 May and where 200 men of the Magdalena battalion of Colonel José María Córdova, who had come from the Cauca River, were incorporated. The rest of the Magdalena battalion (about 400 men) were in Guayaquil and in Cuenca, ill and exhausted. The royalists were in Machachi with about 2,200 infantry soldiers of Nicolás López and about 300 cavalry troops led by Colonel Tolrá covering the passes of Jalupana and La Viudita.

Sucre decided to evade the royalist position by the right. On the 13th, he headed along the Limpiopongo road and climbed the slopes of the Cotopaxi Volcano, where he made camp. On the 17th, he descended to the Chillo Valley. Upon learning of these movements, Colonel Nicolás López retreated to Quito on the 16th.

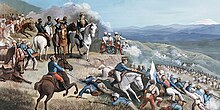

On the 20th, he crossed the hill of Puengasí and the following day he descended to the plain of Turubamba, offering battle in a terrain that was favorable to the Spaniards, who refused to accept it. After several maneuvers to attract the royalists, Sucre flanked the Spaniards on the right and positioned himself in the town of Pasto. Sucre began the march on the night of the 23rd, and at 8 in the morning of the 24th he was on the heights of the Pichincha Volcano, from where he had command of the city of Quito. Upon seeing themselves surrounded, the Spaniards climbed the volcano as well. Due to the difficult terrain, both armies were forced to fight in waves. After the patriot victory in the Battle of Pichincha, Quito was occupied by the Liberator’s Army and Ecuador was in the hands of the pro-independence troops. The following day, Aymerich surrendered by means of the Capitulation of Quito. On 29 May, the Municipality of Quito proclaimed the integration of the former Royal Audience of Quito into Colombia.

Between September 1821 and May 1822, the government of Greater Colombia had sent 137 officers and 7,314 soldiers to support the Liberator’s operations, excluding the contingents sent to Guayaquil to help Sucre, but only 2,000 were active and as many were hospitalized.

Bolívar's Operations Against Pasto

After the Battle of Carabobo, the Constituent Congress of 1821 named Bolívar President of the Republic and Santander as Vice President. [15] Bolívar made arrangements that same year: he organized an army of 4,000 soldiers, entrusted Santander with the Presidency, and headed south. Initially, the Liberator wanted to transport the troops by sea in three brigantines. When he was embarking in the port of Buenaventura, a Spanish squadron appeared, sent by Juan de la Cruz Mourgeón y Achet from the current northern coast of Ecuador. It consisted of one corvette, four schooners, and three transports. The weakness of the Colombian Navy in the Pacific, when compared to the Spanish, forced him to take the land route, which was more arduous due to the difficult terrain of the Andes. That, coupled with illnesses, caused greater casualties in the army than what was expected, and thus he could not replace them with the contingents that he found on the way. Upon arriving in Popayán, he was reinforced with 1,200 men from the division of General Pedro León Torres. He waited in the province of Popayán for reinforcements that he had requested from the government, but when they were not granted, he continued on to Pasto.

The Liberator wanted to avoid Patía and Pasto, knowing the disasters suffered by other commanders in previous years. He preferred to attack Quito, transporting his army by sea to Guayaquil. He also hoped to count on the support of the Chilean Government and of San Martín to liberate Quito. In a letter dated 24 August 1821 and addressed to San Martín, he argued that since the Venezuelan royalists, crushed in Carabobo, would soon find their end in Puerto Cabello, then resources could be destined to Thomas Cochrane's powerful Chilean squadron to transport his army. In October of that year, 4,000 Colombian soldiers would sail from Santa Marta headed to Panama, where they would be joined by 4,000 more troops. From there, both contingents would sail to Guayaquil, where 3,000 republicans were billeted. Finally, more than 4,000 units would leave Buenaventura to reinforce the current Ecuadorian port, with 2,000 or 3,000 rifles in reserve. The force would total 10,000 to 12,000 elements. However, the remoteness of the Peruvian and Ecuadorian coasts from their bases prevented Cochrane from taking action. Finally, Bolívar was satisfied. He abandoned his plans and began to devise the advance of some 4,000 men on Patía and Pasto.

The city of Pasto had been a royalist stronghold since the beginning of the emancipation from New Granada. The territory between Quito and Popayán was in the hands of the Pasto guerrillas, who in the past had destroyed several New Granada armies sent to pacify the region. The resistance of the population, together with the difficult terrain, made the region a position of great defensive capacity. There, the royalist guerrillas led by mixed-raced Pastuso General Agustín Agualongo managed to maintain their resistance for a long time. For example, after the Battle of Boyacá (7 August 1819), the royalist Commander Sebastián de la Calzada, who was garrisoning the city of Santa Fe de Bogotá, retreated two days later to Pasto, where he managed to organize an army of 4,000 men to attack Popayán (24 January 1820). [16] After some clashes in the Cauca Valley, Calzada was relieved of his command and sent to Venezuela while the Pastusos continued waging the resistance. The royalists lost the city of Popayán definitively on 14 July 1820 with the entrance of General Juan Manuel Valdés.

After crossing the Mayo River, the army deviated from the Berruecos Road (the most direct path to Pasto) and took instead the one on the right, with the goal of flanking the positions of the Spaniards, located behind the Juanambú River. After several false crossings, the Colombians managed to cross the river through the Burrero pass almost without resistance, after which they made camp in the Pañol, an area abundant in agricultural products where they took the opportunity to reorganize their forces.

On 2 April, the army continued on their way. When assaulted by the royalist guerrillas, they crossed the ravine of Molinos de Aco, making camp in Cerro Gordo. The army had been reduced by casualties and garrisons to 2,100 troops.

After a day’s rest, Bolívar resumed the march on 4 April on the road to Pasto, but upon reaching the summit near Genoy, where the royalists had fortified the road, they converged to the right towards Mombuco. The same day, they were attacked by royalist guerrillas, but these were shot down by the Bogota battalion and barricaded themselves in the fortifications of Genoy. The following day, the guerrilla attacks continued. After repulsing them, the army continued through the Trapiche de Matacuchos and made camp on the 6th in the town of Consacá, very close to Pasto, while the Bogotá battalion made camp as a vanguard further on, in the hacienda of Bomboná.

The Battle of Bomboná took place on 7 April. In spite of the unfavorable conditions, Bolívar decided to attack because he wanted to arrive on time in Quito, where Sucre would be waiting for him to fight the decisive battle. The royalists, under the command of Basilio García in a solid position, inflicted great losses on the Colombians. The result of this battle was even, with heavy losses on both sides.

The losses in Bomboná forced Bolívar to wait in Cariaco until he received reinforcements. On 16 April, still without news of any reinforcements, Bolívar began his retreat. The following day, he was attacked by a large group of guerrilla fighters while marching along the Genoy road, but they were repulsed by the Colombians. On the afternoon of the 19th, the guerrillas attacked again and were again repulsed.

On 20 April, having replenished his losses, the Spanish commander waged battle at the siege of El Peñol. The combat lasted an hour, after which the royalists retreated. García withdrew to Pasto while Bolívar crossed the Mayo River and made camp in the elevation known as Trapiche. There, he received reinforcements, and his forces again reached 2,000 men.

With the reinforced Colombian army back on the offensive and the news of the defeat at Pichincha, Commander Basilio García capitulated to Bolívar on 8 June as the Colombian Army entered Pasto. Benito Boves fled to the mountains with a great number of the population. The Liberator offered peace to the Pastusos. Among the terms were: respect for their religion, as well as exemption from military service and from the payment of obligatory taxes for the rest of the Colombians. The road between Quito and Bogotá was opened. The royalist cause had been lost, its last defenders were isolated from Spain in the lower Peruvian Sierra and in Upper Peru by San Martín's army. In Bogota, it was expected that they would soon capitulate.

The Pasto Rebellion

While Bolívar and Sucre were in Quito, the Pastusos rebelled under Boves’s leadership. Bolívar sent Sucre to quell the insurrection, but the rebels defeated Sucre on 24 November 1822 at the First Battle of the Cuchilla del Taindalá. Sucre withdrew, pursued by Boves but, after regrouping, he returned and defeated the Pastusos in the Second Battle of the Cuchilla del Taindalá and in the Yacuanquer ravine.

Boves withdrew and headed back to Pasto to prepare his defense and resist until the end. On the evening of 24 December 1822, Marshal Sucre stormed the city, taking advantage of the apparent calm of Christmas Eve. The people of Pasto were not prepared for such a battle, and the Rifles Battalion ruthlessly perpetrated all kinds of excesses, killing more than 400 civilians, including women, the elderly, and children, and forcibly recruiting 1,300 men. Moreover, the order was given to secretly execute 14 illustrious people of the city, who were captured, tied with their hands behind their back, and thrown over a cliff into the Guáitara River. This is one of the darkest and least known episodes in the Colombian Wars of Independence. [17] This is how the old military outpost of the Pasto region was defeated and the rebellion was crushed almost definitively.

Annexation and Conference of Guayaquil

The city of Guayaquil would be the bone of contention between the two Liberators and the site for the meeting that would pave the way for the Colombian intervention in the struggle for Peruvian independence.

At the end of the campaign for the liberation of Ecuador, the city of Quito and the other provinces—with the exception of Guayaquil, which had been constituted as a Free Province since 1820—had declared their annexation to the Republic of Colombia. In Guayaquil, public opinion remained divided between those in favor of the annexation, either to Peru or to Colombia, and those who wished to remain independent of any foreign power.

Both the Protector and the Liberator were in favor of the annexation of the province to their states, but Bolívar would be the one to act decisively, with a military occupation of the city on 13 July and the proclamation two days later of the annexation of Guayaquil to Colombia.

Bolívar and San Martín met on 26 July, and they discussed matters pertaining to the sovereignty of Guayaquil and the war in Peru. Shortly after the conference, San Martín renounced the protectorate. It would not take long for Peru and Colombia to find it necessary to wage war together against the royalists and secure their respective independence. As part of the agreements reached, Bolívar agreed to the sending of six Colombian soldiers to Peru. The first contingent of 3,000 men would arrive in El Callao in April of the following year. [18] With this, the Liberator had between 7,000 and 9,000 men in Peru.

Campaigns in Peru

Background

After the boost to the emancipation project of the Americas that represented José de San Martín's campaigns in the south of the continent at the end of the 1810s, the situation in the Southern Cone was extremely worrying. In the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata, the conflicts between the provinces and Buenos Aires had started to gain strength and the caudillos would have free rein after the Battle of Cepeda. The United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves launched an aggressive policy of southward expansion that, due to its monarchical nature, posed a danger to the independence of the Americas and its nascent democracies. In Peru, San Martín sought a political solution to the war with the coronation of a European prince in the Americas. However, the power struggles between the caudillos, the political ambitions of the oligarchy, and the powerful army that the Spaniards maintained in the country were about to lead to the greatest of all anarchies. All of these conditions had split the emancipation movement into small centers of power, in which the ruling classes zealously clung to it, resulting in a dangerous fragmentation of power that would be unable to withstand an advance of the Spaniards from Peru, let alone attack them. [19]

In the north, on the other hand, they had overcome disunity and drawn together the various social classes and interests to the emancipation movement under the leadership of Simón Bolívar. This had given it a collective nature that broke with the times in which only the aristocracy was interested in maintaining its power and the bourgeoisie in attaining it. After several campaigns, they had liberated a good part of the territory of the former Viceroyalty of New Granada. The latter had been reorganized as a republic, the Greater Colombia, from which Bolívar wished to complete his Americanist dream of uniting the former Spanish dominions into a single republic that would have the strength to resist any attempt at recolonization by Spain or any other power.

After the Battle of Carabobo in 1821, the territory of Greater Colombia was largely secured. Nonetheless, the war would last until 1823 in Venezuela with the fall of Puerto Cabello in the Republican hands of General José Antonio Páez, and some royalist guerrillas would continue in New Granada and Venezuela.

Peru Asks Colombia for Help

After San Martín’s withdrawal, the Constituent Congress appointed General José de La Mar as President of the Governing Junta. De la Mar compromised a large portion of the army in ambitious campaigns that failed in the battles of Torata and Moquegua, leaving the Peruvian Government in a fragile military condition. So much so that, upon learning of the victory in Pichincha, San Martín wrote to Sucre on 24 June 1822 to ask him for the return of the Santa Cruz division plus another one composed of 1,500 to 2,000 combatants, to finish off the Royal Army of Peru. However, the expected reinforcements could not come from Quito’s resources since, as it had been speculated, the province had been destroyed by the war. On 13 July, San Martín accepted the offer of Colombian aid.

On 31 July 1822, the Liberation Army stationed in Lima had 7,491 troops and 397 leaders and officers ready to launch the campaign under the command of General Rudecindo Alvarado. They were organized in the Artillery of Chile Regiment; the Artillery of the Andes Company; Battalions Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, and 11; the Numancia Battalion; the Army Rangers Battalion; the Peruvian Legion Battalion; the Río de la Plata Regiment; the Mounted Grenadiers Regiment; and the Hussars of the Legion or of the Guard Regiment. It was the largest army that had been assembled in the capital of the viceroyalty since the times of Manuel de Amat y Junyent. During the Seven Years' War, he organized the civic militias to raise a host of 5,000 infantry troops and 2,000 cavalry soldiers to protect the Spanish territories from potential attacks by the English or the Portuguese. [20] In the mountains, there were eight troop of mounted rebels, totaling 649 armed men, who were led by five captains, two lieutenants, and a sergeant major. This estimate does not include the parties of commanders Juan Evangelista Vivas in Jauja and Isidoro Villar in Cerro de Pasco. In addition, there were the civic militias that totaled 21,288 “sufficiently armed inhabitants” organized into a force for the northern departments ( Trujillo and the Coast) and another one for Lima Province. The first included one company, three regiments, and four battalions—all infantry—as well as seven regiments (two of dragoons) and four squadrons—all cavalry—from Huaura, Chalaco, Amotape, Querocotó, Pacasmayo, San Pablo, Huambos, Chota, San Marcos de Ferreñafe, Trujillo, Moyobamba, Piura, Huamachuco, San Antonio de Cajamarca, and Lambayeque. In total, 13,970 men. The second one was split into the Peruvian Loyalists Battalion, the Patriot Battalion, and the Peruvian Legion Battalion; the Civic Guard Line Regiment; combat engineers; the artillery brigade of the 4th company of the 1st Creation; the Moran Loyalists Company; the cavalry company in the Loyalist Cavalry Regiment; and the Pardos Squadron. In total, there were 5,584 infantry troops, and 1,734 artillery and cavalry soldiers (7,318 enlisted).

The next return of the Santa Cruz division was also expected, which, due to casualties and replacements, had decreased to 1,604 men organized in the No. 2 Battalion (712 men), the Piura Battalion (477), the mounted grenadiers (123), mounted rangers (277), and an artillery picket (15), considered to have suffered 89 casualties. They would be joined by 1,656 veterans sent by Bolívar who had been taken from the Vencedores de Boyacá, Vencedores de Pichincha, and Yaguachi battalions. They were expected by September. Thus, San Martín would have 10,647 line soldiers and more than 22,000 conscripts to face the 9,530 soldiers whom the viceroy had left in the mountains, according to his sources. Finally, there was the Navy: the frigate Protector; the corvettes Limeña and O'Higgins; the brigantines Belgrano, Balcarce, and Nancy; and schooners Cruz, Castelli, and Macedonia, totaling 126 cannons and 642 crew members. By comparison, in 1805, the viceroy’s forces totaled 23,802 disciplined conscripts and 27,816 urban conscripts in Lima, Arequipa, Cuzco, Trujillo, and Chiloé. [21]

Military defeats and political struggles among the Peruvian patriots weakened the Peruvian pro-independence forces. The government of José de la Riva-Agüero was pressured by public opinion to request the intervention of Bolívar, who was interested in getting involved in Peru. For this, it was necessary to create the proper environment for calling on him. The Liberator, who was in Guayaquil overseeing the events in Peru, responded to the first Peruvian requests by sending the 6,000 men he had already prepared in Ecuador in two successive expeditions of 3,000 each. General Sucre was in command of the forces and in charge of negotiating with Peru the terms under which Bolívar would intervene in the war.

By late February 1823, the royalist forces consisted of 18,000 men: 5,000 from the Army of the North under the command of José de Canterac in the Jauja Valley; 4,000 from the division of Pedro Antonio Olañeta with the garrison of Santa Cruz de la Sierra; 3,000 in Charcas; 3,000 from the Army of the South located between Puno and Arequipa; 1,000 in Cuzco, and 2,000 in other garrisons. [22] The revolutionary leaders, Bolívar in particular, believed that the Peruvian royalist army in 1822 was more powerful than it was two years prior. At the time, they expected to defeat the royalists with 5,000 to 6,000 soldiers.

Around that time, the Liberator promised the governments of Lima to send them 4,000 to 4,500 troops, which he did not have but hoped to gather in Ecuador. However, he soon realized that the ravaged region could not provide him with even 3,000 forcibly recruited men. Besides, the army assembled in Quito and Guayaquil barely numbered 3,000 combatants. He would have to be satisfied with sending 1,700 reinforcements. According to General John Miller, brother of Guillermo Miller, Bolívar had captured a large number of prisoners in Quito, who, when forcibly recruited, increased his army to 9,600 troops. However, since they could not be trusted, he could only support Lima with 1,070 units. The possibility of the Peruvian Army being defeated by the royalists before reinforcements arrived had also been considered, as the remnants would retreat north to join the Colombians. [23]

In an attempt to fulfill his promises, Bolívar asked Santander to send 3,000 soldiers on 29 October 1822 and on 15 April 1823.He also could not leave unguarded the provinces of Loja, Cuenca, Quito, Pasto, and even Guayaquil, where support for the royal cause was still strong and there could be uprisings. The arguments for refusing to send renewed support were the uprising of the Pastusos and the royalist resistance in Puerto Cabello. On 29 August, Bolívar finally ceased his requests. The projected reinforcement of 4,000 men was impossible to maintain once in Peru, where most of them would fall ill or desert—especially, according to him, the recruits coming from Venezuela, the Isthmus, and Cartagena. And even if it were only half of them, it was possible that they would be needed more in Venezuela. Such troops would only be sent when Caracas did not need them. [24] On the other hand, the Peruvians feared that Bolívar would gather too powerful an army, and thus they ended up rejecting the offer of help.

The Second Pasto Rebellion

In mid-1823, with Colombia’s southern region stripped of military troops because they were either in Peru or embarking to go there, the leaders of the Pasto resistance—Estanislao Merchancano as civilian chief and Agustín Agualongo as military chief—rose up in Pasto in support of the King's cause. The people of Pasto were defeated several times, including in Ibarra. But after being defeated, they retreated to the mountains where they regrouped and attacked again. The rebellion finally ended in July 1824 with the capture and execution of Agualongo.

Sucre, Supreme Military Leader

Upon the arrival of the first Colombian expedition to the port of El Callao (3,000 troops, including Venezuelan lancers, grenadiers from New Granada, and mercenary fusiliers from Scotland, England, Germany, Russia, and Ireland), [25] Andrés de Santa Cruz and Agustín Gamarra were in an offensive near La Paz with almost all of the Peruvian forces. Lima had been left almost unguarded by the Peruvian Army, a situation that Brigadier José de Canterac took advantage of to organize an army of 8,000 men in Jauja. With this army, he marched on the capital, entering Lima on 18 June. Congress named Sucre general in chief. On 18 June, with only 3,700 men, Sucre evacuated the city and headed to El Callao. The following days there were several clashes between both advance forces, including a bloody combat at Carrizal and La Legua on 1 July. On 21 June, the Peruvian Congress proclaimed Sucre as Supreme Military Leader.

The 1822–1823 period was one of constant crisis for the revolution in Peru.

Expedition to Intermedios

At a council of war, Sucre recommended sending an expedition of 4,000 men to reinforce the Peruvian forces that were on the high Andean plateau and to force Canterac to evacuate Lima. Congress agreed to the idea and Sucre appointed General Rudecindo Alvarado as chief. The latter left El Callao on 13 July headed for Intermedios with Jacinto Lara’s brigade, composed of three Colombian battalions, and General Pinto’s brigade of two Chilean battalions.

Bolívar and San Martín thought the campaign was too risky, but its proponents hoped that, with a double offensive of 8,000 soldiers, they would be able to annihilate the last royalist enclaves. The Republican troop was too small when compared to the enemy forces, estimated at a total of 19,000 to 20,000 men who could easily assemble between 10,000 and 12,000 in any specific location.

When Canterac learned of the expedition, he evacuated Lima on 16 July and headed south via Jauja and Huancavelica to halt the progress of Santa Cruz and prevent a union of the Peruvian and Colombian armies.

Sucre left El Callao on 20 July and arrived at the port of Chala on 2 August. He took with him 4,500 men, while 11,000 veterans remained garrisoned in Lima. There, he asked Santa Cruz for help, but disagreements between the two destroyed any hope of working together. From Quilca, Sucre continued on to Arequipa, which he took on 18 August. The Spanish garrison retreated to Apo.

Meanwhile, in the mountains, the forces of Jerónimo Valdés and the Viceroy had assembled. Santa Cruz avoided combat and headed towards Oruro to meet with Gamarra. There, they received news that General Olañeta had arrived from Potosí to join the viceroy’s army.

Sucre received a letter from Santa Cruz on 12 September, inviting him to meet, but by the time he arrived in Apo he learned of Santa Cruz’s and Gamarra’s retreat. After heading for Puno, he learned there that the Peruvian Army was retreating to the coast and Sucre. He headed back and reached Cangallo, a city located on the road to Moquegua, from where he returned to Arequipa on 29 September.

Arrival of Bolivar

Bolívar left Guayaquil on 6 August of that year on the brigantine Chimborazo. After 25 days of sailing against the southern current, he docked the Chimborazo in the port of El Callao on 1 September, and then entered Lima on the 10th amid great celebrations. The Peruvian Congress named him Supreme Director of War. In the days that followed, Colombian reinforcements continued to arrive in El Callao.

Confrontation with Riva Agüero

Bolívar had to face the machinations of former President José de la Riva Agüero, who, after being removed from office by Congress, had retreated before Bolívar's arrival in Trujillo with his army of 3,000 men and refused to submit to the authority of new President José Bernardo de Tagle. [26] The day after his landing in Peru, Congress had authorized Bolívar to put an end to the dissension between Riva Agüero and the government presided by Torre Tagle. On the 4th, Bolívar addressed a letter to Riva Agüero urging him to submit to Congress. With the supreme military authority conferred upon him by Congress on the 10th of that month, Bolívar had sufficient scope of action to take the necessary political and military measures.

Bolívar appointed a commission composed of Representative José María Galdeano and Brigadier General Luis Urdaneta to deal with Riva Agüero. On 11 September, they arrived at the headquarters in Huaraz without having reached an acceptable agreement with the dissident, as he was waiting for favorable news from Santa Cruz's army and the negotiations he was carrying out with the Spaniards.

Bolívar invited Riva Agüero several times to add his men to the 3,000 that the former had in Paseo, in order to launch the campaign that he would lead against the Spaniards. Meanwhile, Sucre sought to bring Santa Cruz closer and thus cut off the latter's support for Riva Agüero. Bolivar then learned of the dissolution of Santa Cruz’s army along with the alarming news that Riva Agüero was seeking an agreement with Viceroy José de la Serna. Having exhausted diplomatic resources, the Liberator began preparations to reduce Riva Agüero by force.

By late that month, the military situation was as follows: the royalists were divided into the Army of the North (6,000 men) in the district of Cusco under the command of the Viceroy, and the Army of the South (3,000) in Upper Peru under the command of Jerónimo Valdés. Meanwhile, the republicans, under Bolívar’s command, had about 7,000 soldiers left, out of the 9,000 to 10,000 with whom they had started the campaign. [27] These numerous casualties were not new. Between mid-1818 and June 1822, more than 22,000 Colombians had been recruited but only 600 were still active. The rest had either died, were sick or wounded, or had deserted.

Bolívar would express his opinion of the chaotic Peruvian situation (three governments, Riva Agüero in Trujillo, Torre Tagle in Lima, and La Serna in Cuzco):

The Pizarro brothers and Almagro fought; La Serna fought with Pezuela; Riva Agüero fought with Congress, Torre Tagle with Riva Agüero, and Torre Tagle with his homeland; now, Olañeta is fighting with La Serna and, for the same reason, we have had time to regroup and to stand in the arena armed from head to toe.

— Letter from Bolívar to Santander, Huamachuco, May 6th, 1824 [28]

Military Campaign Against Riva Agüero

The rebels were in Huaraz and Trujillo and the Viceroy was in Jauja and Cerro de Pasco. Bolívar decided to confront both by occupying the territory between the two armies and thus preventing them from joining forces. Sucre had refused to take part in the campaign against the Peruvian rebels, as he believed that he should not interfere in the affairs of that nation. Therefore, Bolívar assigned them to contain the Spaniards in Jauja and Pasco. The campaign in the south against Santa Cruz’s forces had mobilized many of the men available to the Viceroy in the north, leaving a few in the area where Bolívar and Sucre were operating.

I went out to stand in the way between Riva Agüero and the loyalists in Jauja, because this wicked man, desperate for victory, was trying to surrender his homeland to the enemy in order to gain more profit even if he is less successful.

— Bolívar to Santander, Pallasca, December 8th, 1823.

The republicans numbered 15,000 men, distributed as follows at the beginning of September: 6,000 with Santa Cruz in La Paz, 3,000 with Sucre in Arequipa, 4,000 in the outskirts of Lima, and 2,000 following Riva Agüero in Trujillo, besides the 2,000 reinforcements that were expected from Chile. [29] The royalist forces totaled 18,000, as follows: 8,000 with Canterac in Jauja, 3,000 with Valdés between Puno and Arequipa, 4,000 with Olañeta in Charcas, 1,000 with the viceroy in Cuzco, and 2,000 in other areas. But the need to face Santa Cruz forced him to weaken the forces in the north, leaving 3,000 in Jauja and Ica, and concentrating 4,000 in Arequipa. Sucre was forced to avoid facing superior forces, and thus he had to retreat to Lima or join Santa Cruz.

With the Colombian troops—3,000 soldiers [30]—Bolívar climbed from the coast towards the Cordillera Negra; next, through the valleys of Pativilca and the fortresses; then he crossed the Summit, and finally descended to the Callejón de Huaylas. The bulk of the army marched towards Huaraz, where Sucre and his division joined in. Sucre was entrusted to cross the mountain range with some select soldiers and head south to face the Spaniards who were in the regions of Huánuco and Pasco. Meanwhile, Bolívar headed north directly against Riva Agüero, who had retreated to Trujillo. While the campaign was developing in the mountains, on the coast, Admiral Guisse pronounced himself in favor of Riva Agüero and established the blockade of the whole Peruvian coast from Cobija to Guayaquil.

Riva Agüero avoided combat with the Colombian troops until 25 November, when he was removed from office along with his second in command, General Ramón Herrera, by his subordinates, who were against the former president’s deals with the Spaniards. General La Fuente arrested Riva Agüero in Trujillo, while Colonel Ramón Castilla did the same in Santa, arresting General Ramón Herrera. Bolívar remained in the western mountain range, where he was chasing Riva Agüero's subordinates who had retreated to the Marañón River and were surrendering along Bolívar’s path.

Upon the campaign’s end, the army was exhausted, tired of marching through the high mountain ranges and with its equipment worn out and with no possibility of replacing it. Bolívar asked Colombia for reinforcements, but these would only begin to arrive when the war was practically over.

Rebellion of the Argentine Forces

On 5 February 1824, the soldiers of the Río de la Plata Regiment rebelled in El Callao, together with some Chilean and Peruvian units, due to delays in their payments. They captured their officers, among them General Alvarado, governor of the city’s fortresses. The rebels freed Colonel José de Casariego, a Spanish royalist, and gave him command of their forces. A few days later, the Mounted Grenadiers joined the rebellion from Lurín. A hundred of them protested the action and, under the command of José Félix Bogado, they managed to join the Liberator’s army, forming a squadron that fought in Junín and Ayacucho, returning later to Buenos Aires.

At once, Bolívar ordered to take all the military and logistics corps possible out of Lima before the arrival of the Spanish Army to support the rebels in El Callao. In view of the serious military situation, Congress appointed him Dictator with unlimited powers through a resolution dated 10 February.

Military Situation

The army was then made up of only 5,000 men—4,000 Colombians and 1,000 Peruvians. Apart from that, about 750 Colombians had fallen ill due to the long walks and soroche or altitude sickness. By 30 March, the main corps of the Colombian Army were on the coast and the Callejón de Huaylas. On the other side of the Cordillera Blanca, a Colombian battalion and squadron and two Peruvian corps protected the entrance by serving as an advance guard. North of Trujillo, there were three Peruvian and two Colombian battalions. The Spanish Army was on the other side of the mountain range, in the valleys of Jauja and Tarma, thus confronting the Colombian-Peruvian forces. Meanwhile, desertions continued in several Peruvian units, and Lima, unoccupied by the Liberation Army, was occupied by the royalists on 18 June while the pro-independence garrison took refuge in El Callao. [31] This chaotic situation in the Peruvian Government would last until 16 July, when the capital city was occupied by Sucre after the evacuation of the soldiers and supporters of royalism that had started on the first day of that month. The garrison, until then besieged in El Callao, left and entered the city. [32] Four days later, Sucre would leave Lima to help Santa Cruz in the Second Intermedios Campaign.

Reorganization of the Liberation Army

Faced with the chaotic political-military situation, Bolívar took energetic action to avoid the collapse of the Peruvian state, which seemed imminent. Desertions continued among the Peruvian forces, and even former President Torre Tagle joined the Spaniards. In the meantime, Bolívar was reorganizing his forces based on the Colombian Army. He asked for reinforcements from Bogotá while he remained on the offensive. Sucre and Bolívar were arguing about the military strategy to follow. Sucre wanted to make a preventive attack to take Jauja and reach the Izcuchaca Valley, while Bolivar preferred to save his strength until he had received reinforcements, and thus was opposed to occupying land that they would not be able to consolidate. The reinforcements sent by Páez from Venezuela would arrive in May.

In total, the Liberator had requested up to 37,000 reinforcements during the Peruvian campaign to Bogotá (3,000 on 3 March 1823; 6,000 on 4 August; 12,000 on 22 December, and 16,000 on 9 February 1824). Only 2,500 arrived (500 in December 1823, 900 on 27 March 1824, and 1,100 on 22 May). This difference between the number of men requested and those sent can be found from Carabobo—more than 20,000 men wanted to mobilize in New Grenada but there were barely 6,400 in the republican army. Another example is that in early 1822, Bolívar asked Santander for 2,000 reinforcements in order to have 4,000 men with whom to advance from Popayán to Quito. As he never got them, the Liberator was satisfied with 2,000 combatants. The reasons were in the scant support of the Colombian Congress and the danger that Francisco Tomás Morales represented, as he pointed out in a letter dated 29 April 1823, in which he accused the Colombian politicians of abandoning to their fate “15,000 men from four nations” who were fighting in Peru.

On the other hand, he constantly asked for support from the governments of Santiago, Buenos Aires, Mexico, and Guatemala. Only Chile made an economic contribution of one million pesos to Peru, but also with an auxiliary troop during the Second Intermedios Campaign. Bolívar would ask the Chilean Government of Ramón Freire to send 3,000 soldiers to conquer the north of El Callao, from Supe to Huanchaco, and prevent the royalist victory in Peru, which directly affected Santiago, as he relates in a letter dated 18 January 1824. With this added to the reinforcements he expected from Colombia, victory would be certain, but neither Freire had the resources, nor the Chilean Congress was willing to get involved in the factional struggle that was taking place in Peru.

Olañeta's Dissidence: Colombian Offensive

General Olañeta, contrary to the liberal tendencies of Viceroy La Serna, rebelled in Potosí. The viceroy decided that Bolívar was the lesser threat. Therefore, believing that the latter would continue to wait for reinforcements without moving, he sent Jerónimo Valdés to put an end to Olañeta, which he almost achieved after his victory in the battle of Lava. The royalist forces were mortally divided, and everything would end for them in Ayacucho. By then, the United Army of Peru totaled 8,080 combatants (5,123 infantry troops and 589 cavalry soldiers from Greater Colombia, and 1,727 infantry troops, 519 cavalry soldiers, and 25 gunners with some pieces from Peru). [33] The patriot forces in Peru totaled 8,000 combatants from Greater Colombia and 5,000 from Peru by late 1824. [34]

See also

References

- ^ Hooker, Terry D. (1991). The armies of Bolivar and San Martin. London: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-85532-128-9.

-

^ Lumbreras, Luis Guillermo (2003). Historia de América andina: Creación de las repúblicas y formación de la nación. Tomo V. Quito: Libresa. p. 165.

ISBN

978-9-97880-759-0.

For the Popayán and Quito campaigns, Bolívar recruited 5,000 slaves who were freed after two years of service. Bolívar's attitude towards slavery tends to be considered as "pragmatic" as it changed according to the circumstances.

- ^ Restrepo Tirado, Ernesto (1916). Archivo Santander. Tomo VII. Bogota: Aguila Negra Editorial. p. 257.

- ^ de Sucre, Antonio José (1973). Archivo de Sucre: 1812-1821. Tomo I. Caracas: Fundación Vicente Lecuna. p. 519.

-

^ Flores y Caamaño, Alfredo (1960). Objeciones históricas: a la obra intitulada: "Angel Grisanti. El gran mariscal de Ayacucho y su esposa la marquesa de Solanda. Caracas, Imprenta Nacional, 1955" y a tres anteriores del mismo origen. Lima: Editorial Salesiana. p. 281.

He estimates that the provinces of Guayaquil, Ecuador (Quito), and Azuay could support 4,000 to 5,000 soldiers perfectly well if they set their minds to it.

- ^ Macías Núñez, Edison (1997). El capitán Abdón Calderón Garaycoa, soldado, héroe y mártir. Quito: Centro de Estudios Históricos del Ejército. p. 90.

- ^ Macías Núñez, Edison (1997). El capitán Abdón Calderón Garaycoa, soldado, héroe y mártir. Quito: Centro de Estudios Históricos del Ejército. p. 90.

- ^ Núñez Sánchez, Jorge (2002). El Ecuador en la historia. Quito: Archivo General de la Nación. p. 134. ISBN 9789945074451.

- ^ Macías Núñez, Edison (1997). El capitán Abdón Calderón Garaycoa, soldado, héroe y mártir. Quito: Centro de Estudios Históricos del Ejército. p. 90.

- ^ Vargas, Francisco Alejandro (1970). Guayaquil y sus libertadores. Quito: Archivo General de la Nación. p. 13.

-

^ Encina, Francisco Antonio (1954). Bolívar y la independencia de la América Española. Emancipación de Quito y Alto y Bajo Perú. Tomo V. Santiago: Nascimiento. p. 50.

On 12 June 1821, Sucre asked San Martín for 800 to 1,000 men to attack Quito.

- ^ Paz Soldán, 1868: 250. Letter from Sucre to brigadier and war minister Tomás Guido, Cuenca, 25 February 1822; letter from Juan Antonio Álvarez de Arenales to Sucre, Lambayeque, 3 January 1822.

- ^ Seminario Ojeda, Miguel Arturo (1994). Piura y la independencia. Instituto de Cambio y Desarrollo. Prologue by Miguel Maticorena Estrada, pp. 156. According to a report from Santa Cruz, 31 May 1822, Quito.

- ^ Andrade Reimers, Luis (1995). Sucre en el Ecuador. Quito: Corporación Editora Nacional. p. 94. ISBN 9789978840290.

- ^ Encina, 1954: 63. After retaking Caracas, Bolívar turned his attention to Peru. On 16 August 1821, he wrote to Santander in Tocuyo, requesting 4,000 to 5,000 soldiers to advance on Peru and obtain victories such as Boyacá and Carabobo.

- ^ Francisco Pí y Margall & Francisco de Pi y Arsuaga (1903). Historia de España en el siglo xix: sucesos políticos, económicos, sociales y artísticos. Tomo II. Madrid: Seguí, pp. 545.

- ^ Bastidas Urresty, Édgar (2010). Las guerras de Pasto. Colección Bicentenarios de América Latina. Bogota: Fundación para la Investigación y la Cultura (FICA). ISBN 958-9480-37-3.

- ^ Soria, Diego A. (2004). Las campañas militares del General San Martín. Buenos Aires: Instituto Nacional Sanmartiniano. p. 145. ISBN 978-9-87945-962-1.

- ^ Liévano Aguirre, Indalecio (1983). Bolívar. Madrid: Cultura Hispánica del Instituto de Cooperación Iberoaméricana. ISBN 84-7232-311-0.

- ^ Palma, Ricardo (2014). Tradiciones limeñas. Barcelona: Linkgua digital. p. 68. ISBN 9788490075999.

- ^ Maldonado Favarato, Horacio & Carcelén Reluz, Carlos (2013). “El ejército realista en Perú a inicios del XIX. Las nuevas técnicas de artillería e ingeniería y la represión a los alzamientos en Quito y el Alto Perú”. Cuadernos de Marte Magazine. Year 4, No. 5, July—December 2013: 9-43 (see pp. 16).

- ^ Torrente, Mariano (1828). Geografía universal física, política é histórica. Tomo II. Madrid: Imprenta de Don Miguel de Burgos. p. 488.

- ^ Encina, 1954: 207. In that case, 6,000 to 8,000 troops were expected to be assembled. Ibid.: 208-209. Bolivar claimed that San Martín’s situation in Peru was bad, despite having 2,000 soldiers more than the enemy. If the latter was defeated, the former claimed to be ready to do anything to raise 8,000 to 10,000 men and finish them off definitively.

- ^ Encina, 1954: 206. The troops were to leave Caracas, cross through Panama, and reach Peru.

- ^ Fagúndez, Carlos & Marcano de Fagúndez, Carmen (2006). Simón Bolívar: año tras año: 1783-1830. Total Print 29, pp. 214.

- ^ Roca, José Luis (2007). Ni con Lima ni con Buenos Aires: la formación de un estado nacional en Charcas. Plural editores. p. 607. ISBN 9789995410766.

- ^ Torrente, Mariano (1828). Geografía universal física, política é histórica. Tomo II. Madrid: Imprenta de Don Miguel de Burgos, pp. 488

- ^ Lasheras, Jesús Andrés (2001). Simón Rodríguez. Cartas. Simón Rodriguez National Experimental University (UNERSR), pp. 107. Foreword by Pedro Cunill Grau. ISBN 9789802880164.

- ^ Rivas Vicuña, Francisco (1940). Las guerras de Bolivar: historia de la emancipacion americana. Perú, 1822-1825. Tomo VI. Santiago: Editorial El Esfuerzo, pp. 10.

- ^ Fagúndez, Carlos & Marcano de Fagúndez, Carmen (2006). Simón Bolívar: año tras año: 1783-1830. Total Print 29, pp. 218.

- ^ Encina, 1954: 210. While José de Canterac was entering Lima, Bolívar wrote to his men in El Callao, promising to send 6,000 men so that they could double the number of royalists and oust them. Ibid.: 270. On 30 May, after a war council, Riva Agüero and Sucre decided to shelter the 3,000 soldiers they had in Lima and its surroundings in El Callao, where 2,000 combatants were already entrenched (troops that were essential to secure the fortress). In the meantime, Canterac was advancing with 9,000 royalists to Lima, while the same number of royalist soldiers was dispersed in Upper Peru and in a vulnerable position against Santa Cruz. Ibid.: 271. Santa Cruz would still have about 3,000 men with whom he could advance to Desaguadero, the viceroy's line of defense.

- ^ García Gambra, Andrés (1825). Memorias del General García Gambra para la historia de las armas españolas en el Perú (1822-1825). Tomo II. Madrid: Editorial-América. Ayacucho Library under the direction of Rufino Blanco-Fombona, pp. 86.

- ^ Saavedra Galindo, José Manuel (1924). Colombia libertadora: la obra de la Nueva Granada, y especialmente del Valle del Cauca, en la campaña emancipadora del Ecuador y del Perú. El ejército boliviano, fundador de cinco repúblicas, en la ruta del sur. Bogotá: Editorial de Cromos Luis Tamayo & Co., pp. 79.

- ^ Morote Rebolledo, Herbert (2007). Bolívar, libertador y enemigo no. 1 del Perú. Lima: Jaime Campodónico Editor, pp. 80. ISBN 9789972729621.

Bibliography

- Cisneros Velarde, Leonor; Lumbreras, Luis Guillermo; López Mendoza, Víctor (2005). Historia general del Ejército peruano. El ejército de la república. Lima: Permanent Commission of History of the Army of Peru.

- Lecuna, Vicente (1983). Bolívar y el Arte Militar. New York: The Colonial Press INC.

- Paz Soldán, Mariano Felipe (1868). Historia del Perú independiente. Primer período, 1819-1822. Lima: Alfonso Lemale Press.