| Battle of Riggins Hill | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Civil War replica cannon at Fort Defiance in Clarksville | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| William Warren Lowe | Thomas Woodward | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,100 | 700 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| negligible | 107 | ||||||

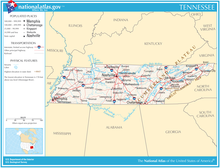

The Battle of Riggins Hill (September 7, 1862) was a minor engagement in western Tennessee during the American Civil War. A Confederate raiding force under Colonel Thomas Woodward captured Clarksville, Tennessee, threatening Union shipping on the Cumberland River. Several Union regiments led by Colonel William Warren Lowe advanced from nearby Fort Donelson and drove off the Confederates after a struggle lasting less than an hour. The action occurred during the Confederate Heartland Offensive but only affected the local area.

Background

In November 1861, the Confederates built a three-gun fort on the Cumberland River, downstream from Clarksville, to protect the nearby railroad bridge that spanned the Cumberland and Red Rivers. By early 1862, there were two forts guarding the river; Fort Sevier, armed with two 12-pounder long guns and one 42-pounder gun, and farther upstream, low-lying Fort Clarke with two 24-pounder long guns and one 32-pounder gun. [1]

Federal commander Ulysses S. Grant's capture of Fort Donelson on 11–16 February 1862 forced the Confederates to give up Kentucky and a large portion of Tennessee. [2] On 19 February, the gunboats USS Cairo and USS Conestoga and a number of transport vessels with Union infantry steamed up the Cumberland River. Commodore Andrew Hull Foote led the Federal naval force which first found and destroyed the Cumberland Iron Works. Later that day, Foote's expedition found the two forts abandoned, disembarked its infantry at Trice's Landing, and occupied Clarksville without fighting. Union forces soon occupied the state capital Nashville. Fort Sevier was renamed Fort Defiance, enlarged, and garrisoned in April by a small body of Union soldiers under Colonel Rodney Mason of the 71st Ohio Infantry Regiment. [1]

On 4 July 1862, John Hunt Morgan left Knoxville, Tennessee with 900 Confederate cavalrymen. For three weeks, Morgan's raiders rampaged through Kentucky, capturing and paroling 1,200 Union troops, seizing hundreds of horses, and destroying stockpiles of Federal supplies. The hugely successful raid caused President Abraham Lincoln to remark, "They are having a stampede in Kentucky", and compelled the Federal government to assign thousands of troops to garrison duty. [3] On his return at the end of July, Morgan insisted to General Edmund Kirby Smith that an invasion of Kentucky would cause 25,000–30,000 men to enlist in the Confederate army. [3] On 13 August, Kirby Smith's army began to move north, initiating the Confederate Heartland Offensive. [4] On 30 August, Kirby Smith's troops obliterated two brigades of Union recruits at the Battle of Richmond. The Confederates went on to occupy Lexington, Kentucky and threaten Cincinnati. However, the hoped-for thousands of Kentucky recruits did not show up. [5]

On 13 July, Nathan Bedford Forrest and his Confederate cavalrymen forced the Union garrison to surrender in the First Battle of Murfreesboro and destroyed 200,000 rations needed for Don Carlos Buell's Union Army of the Ohio. On 18 July, Forrest destroyed two key railroad bridges in Tennessee, further delaying the re-supply of Buell's army. On 10 August, Morgan's raiders captured Gallatin, Tennessee along with its Federal garrison and burned out the railroad tunnel north of town. When Union cavalry gave chase, Morgan routed them at Hartsville on 19 August and captured their commander, Richard W. Johnson. [6] On 26 August, Braxton Bragg led his Confederate army north from Chattanooga, Tennessee, heading for Kentucky via Sparta, Tennessee. By 29 August, Buell ordered his army to retreat toward Nashville. [7]

Battle

July and August 1862 saw a significant increase of Confederate guerilla warfare in the Clarksville area. On 18 August, Thomas Woodward's 2nd Kentucky Cavalry Regiment captured Clarksville and obtained the surrender of Colonel Mason and his garrison. [1] Mason had not distinguished himself at the Battle of Shiloh on 6 April. [8] He was soon disciplined and demoted for surrendering so easily. On 5 September 1862, a 1,100-man Union force led by Colonel William W. Lowe left Dover, Tennessee with the goal of recapturing Clarksville. Lowe's expedition included detachments of the 5th Iowa Cavalry Regiment, the 71st Ohio, 11th Illinois, and 13th Wisconsin Infantry Regiments, and one section each from James P. Flood's Battery C and Andrew Stenbeck's Battery H, 2nd Illinois Light Artillery. [1] [note 1] Batteries C and H were stationed at Fort Donelson for much of the war. [9]

Skirmishing began on 6 September as Lowe's Union troops advanced toward Clarksville and were delayed by Woodward's Confederates. The Federals pushed their opponents through a one-time town called New Providence. [1] Woodward's 700 defenders included the dismounted 2nd Kentucky Cavalry and some armed civilians. On 7 September, Woodward deployed his men facing west on a north–south ridge called Riggins Hill. This is on modern U.S. Route 79 at Dotsonville Road. The Confederates took cover behind homes, farm buildings, trees, fences, and stone walls. Lowe positioned his troops along a ridge to the west and ordered his artillery to bombard the defenders. [10] Lowe placed the 13th Wisconsin on the left, the 11th Illinois in the center, the 71st Ohio on the right, and the 5th Iowa Cavalry in reserve. [1] After 45 minutes of shelling, Woodward's men began to waver. At this time, Lowe's flanking units pressed forward and the Confederates took to their heels. The Union cavalry pursued their fleeing enemies through Clarksville. Woodward's force suffered losses of 17 killed, 40 wounded, and about 50 captured. Lowe's losses were negligible. [10]

Aftermath

Lowe's soldiers took control of Clarksville and reopened the Cumberland to Union river traffic. However, because not enough troops were available, Clarksville was not permanently occupied until December 1862. The area remained subject to Confederate raids until the end of 1864. [10]

Historical markers

A battle marker is located at U.S. Route 79 and Magnolia Drive within the city limits of Clarksville. There are several other historical markers nearby, including markers for Fort Defiance, Fort Sevier, Trice's Landing, and Forts Versus Ironclads. [10]

Notes

- Footnotes

- ^ Battledetective identified Battery H's commander as Starbuck, but the Official Army Register (p. 216) listed Andrew Stenbeck as the captain.

- Citations

References

- "Battle Study #23". Battledetective Case Files. 2007. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- Boatner, Mark M. III (1959). The Civil War Dictionary. New York, N.Y.: David McKay Company Inc. ISBN 0-679-50013-8.

- Dyer, Frederick H. (1908). A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion: Batteries C to L, 2nd Illinois Light Artillery. Des Moines, Iowa: Dyer Publishing Co. pp. 1040–1042. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- Morfe, Don; Fisher, Bernard (2013). "Battle of Riggins Hill: Fight for Control". The Historical Marker Database. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- Noe, Kenneth W. (2011). Perryville: This Grand Havoc of Battle. Lexington, Ky.: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-3384-3.

- "Official Army Register of the Volunteer Force of the United States Army, Part VI". Washington, D.C.: Secretary of War. 1867. p. 216. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- Smith, Timothy B. (2014). Shiloh: Conquer or Perish. Lawrence, Kan.: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-2347-1.