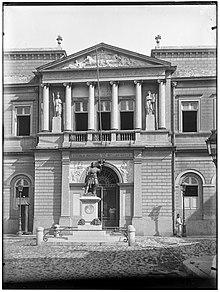

Entrance of the Academy building (Photographed by

Marc Ferrez, in 1891). Today, it is the entrance to the

Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden. | |

| Established | 1816 |

|---|---|

| Location | , |

The Imperial Academy of Fine Arts ( Portuguese: Academia Imperial de Belas Artes) was an institution of higher learning in the arts in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, established by King João VI. Despite facing many initial difficulties, the Academy was established and took its place at the forefront of Brazilian arts education in the second half of the nineteenth century. The Academy became the center of the diffusion of new aesthetic trends and the teaching of modern artistic techniques. It eventually became one of the principal arts institutions under the patronage of Emperor Dom Pedro II. With the Proclamation of the Republic, it became known as the National School of Fine Arts. It became extinct as an independent institution in 1931, when it was absorbed by the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and became known as the UFRJ School of Fine Arts, which still operates today.

Origins

The foundation of art schools in Brazil came from, according to Rafael Denis, Francophile initiatives headed by the ministry of Dom João and the Conde da Barca. These schools were seen as necessary for the formation of specialized professionals to serve the State and its nascent industries. In the early nineteenth century, the educational system was practically non-existent and artistic training was primarily transmitted through apprenticeships. It was thought that, by contracting foreign professors from places like Paris, the school could bring art education to Brazil.

Contact was made with Joaquim Lebreton at the Institut de France in the area of Fine Arts and a group of educators was assembled. [1] However, the origins of the school are debated among historians. It is unclear whether Dom João, the Marquis of Marialva, Lebreton, or French artist Nicolas-Antoine Taunay came up with the idea of bringing arts education to Brazil. [2] [3] In any case, Lebreton ultimately took charge of the project and brought a cohort of instructors to Brazil. Within the group, there was a naval architect ( Grandjean de Montigny), a mechanical engineer, a master ironsmith, carpenters, and various artisans in addition to traditional artists (including painter Nicolas-Antoine Taunay). The most famous member of the group was painter, Jean-Baptiste Debret, the illustrious student of celebrated artist Jacques-Louis David. Both Montigny and Taunay had won the prestigious Prix de Rome.

They arrived in Rio de Janeiro on 26 March 1816 aboard the Calpe and escorted by the Royal English Navy. A few brought their families and servants or sent for them later. This expatriate group formed a small colony that came to be known as the Missão Artística Francesa, or French Artistic Mission. The Mission strengthened the human, technical, and conceptual resources that structured the Escola Real de Ciências, Artes e Ofícios. The first institute of its kind in Brazil, the Real School was founded by royal decree on 12 August 1816. [1] [4] [5] The educational program was outlined by Lebreton, according to a letter his sent to Dom João on 12 June of the same year. In it, Lebreton divides the cycle of artistic apprenticeship into three phases, diverging from the system established by the Royal French Academy of Painting and Sculpture: [6]

Those phases were:

- General design and copying the work of masters.

- Landscapes and basic sculpting.

- Detailed painting and sculpting with the use of live models and study in the worships of master artists.

Architecture students also had a three-tiered system divided by theory and practice.

Theory:

- The history of architecture

- Construction and Perspective

- Stone masonry

Practice:

- Design

- Copying and Studying Dimensions

- Composition

Lebreton also regulated the process and criteria necessary for student evaluation, the schedule of classes (which included outside subjects like music), and paired alumnists with public works projects. He also expanded the school's official art collection and balanced the budget. Lebreton was fundamental in the formation of another arts institution, the Escola de Desenho para Artes e Ofícios (School of Design for the Arts and Trades), whose curriculum was equally rigorous but provided free instruction. [6]

Early years

The project, representative of Academism, had a profile in contrast with the educational system and the circulation of artistic knowledge already in place in Brazil. The country had a long and rich artistic history, seen in the vast collection of Baroque artwork that has survived. The implementation of fine arts education represented a break in methodology for artists. Previously, the informal apprenticeship model, dating back to the medieval period, determined the status of artists based on the notoriety of their masters. Artists were generally considered part of the general population of specialized artisans and their influence on society was marginal. Thematically, most art during this period focused on religious themes because the Catholic church was the greatest patron of the arts. The art world of Colonial Brazil did not have the ability to produce the "palatial" art that the recently arrived royal court desired. This explains the rapid support given to Lebreton's project by the exiled monarchy. It was seen as the beginning of Brazil's evolution into a "civilized" nation. [7]

Members of the Mission arrived in Brazil filled with high expectations, as Debret wrote:

"We were all animated by a similar zeal and, with the enthusiasm of wise travelers that no longer feared facing the vicissitudes of a long and often dangerous voyage, we left France, our shared homeland, to go study an unknown environment and impress upon this new world the profound and useful influence—we hoped-- of the presence of French artists".

[8]

The reality, however, was in contradiction with the expectations of the members of the Mission. Despite royal support, the Mission, proponents of Neoclassicism, encountered resistance among native artists who still followed a Baroque aesthetic and already-established Portuguese professionals, who felt their positions were threatened. French artists were received poorly by both Portuguese and Brazilian residents alike. The government had many other pressing concerns and was not able to give much attention to the school and its affairs. The Conde da Barca, one of the founders and principal promoters of the project, died a year after its inception. The contract for the artists came under fire and the French Consul in Brazil, a supporter of the restored Bourbon monarchy, did not approve of the presence of Napoleonic supporters like Lebreton under the patronage of the court. [4] [8]

The school lacked an ideological base and remained at the mercy of changing political currents. The artists were able to survive on the pension granted to them by the government and supplemented their income by accepting commissions for portraits and organizing elite parties for the court. There were few classes available for enrollment, given the precarious conditions artists like Debret faced in their small artisanal workshops in neighborhoods near Catumbi. Within the Mission group itself, internal divisions also developed. Lebreton was accused of favoritism and mismanagement of funds and had to separate himself from the group. He died shortly after in 1819. He was succeeded by Portuguese painter Henrique José da Silva, a staunch opponent of the French. His first official act as the director of the newly titled institution (then the Academia Real de Desenho, Pintura, Escultura e Arquitetura Civil) was to remove all members of the Mission group from their teaching positions. The resultant hardships endured by the group forced sculptor Auguste–Marie Taunay to leave Brazil (and his son, Félix) in 1821. Taunay died shortly after reaching France. This left the group with only five of its original members: Debret, Nicolas and Auguste Taunay, Montigny, and Ovide. [9] [10]

Despite all the obstacles and controversies, the French Mission group left an indelible mark on the Brazilian cultural scene. They planted a seed that, only later, came to fruition. Debret and Montigny became a nucleus of endurance for the group. Debret was named the official portrait artist for Dom Pedro I and Montigny was responsible for several architectural and urban planning that contributed to the renovation of the face of Rio de Janeiro. [4] Lebreton, in turn, with the curriculum plan he established in 1816, left methodological guidelines that with some modifications remained guiding the evolution of the institution throughout the nineteenth century. [5] Both artists had a profound impact on students at the school. Some of the first students became famous in their own right, like: Simplício Rodrigues de Sá and José de Cristo Moreira (Portuguese); Afonso Falcoz (French); Manuel de Araújo Porto-Alegre, Francisco de Sousa Lobo, José dos Reis Carvalho, José da Silva Arruda, and Francisco Pedro do Amaral (Brazilian). [11]

The Imperial period

After the Independence of Brazil, in 1822, the school became known as the Academia Imperial das Belas Artes and, later, as the Academia Imperial de Belas Artes. The institution was definitively installed in its own building, erected by Montigny, on 5 November 1826. The building was inaugurated by Emperor Pedro I. [12] As the first director of the Academy, Henrique José da Silva was responsible for an important modification to Lebreton's original project. Silva suppressed courses in stone cutting, mechanics, and engraving, claiming that basic design instruction was sufficient for a country without artistic culture like Brazil. In his memoirs about the early years of the AIBA, Debret lamented the end of the technical trades which, according to him, forced the institution toward, "the errors and vices of the ancien régime". [13]

First exhibition

The Academy was responsible for the first art exposition in Brazil. It was titled, "Exposition of Historic Painting" and took place in 1829. The exposition was decreed by the Emperor in a Ministerial Advisory on 26 November 1828, reading:

- His Majesty the Emperor. On Tuesday, the 2nd day of the coming month of December, there will be a public exposition of all of the best works produced at the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts by students from their respective classes in the current year. His Majesty has ordered, for this purpose, a preparatory conference intended to benefit the said exposition; with the participation of members of the Academy on Saturday, the 29th of the current month, at eleven o'clock in the morning, in order to that His Majesty can hear them and arrange this situation definitively-- God Save His Majesty-- 26 November 1828— José Clemente Pereira.

The following year Debret and Grandjean de Montigny, with their own works and those of their students, presented forty-seven pieces of artwork, one hundred and six architectural designs, four landscapes, and four busts sculpted by Marc Ferrez. The exposition was a success—visited by more than two thousand people, covered by newspapers, and organized into a commemorative catalogue. Among the stand-out pieces, Debret had ten paintings, including: A Sagração de D. Pedro I, O Desembarque da Imperatriz Leopoldina, and Retrato de D. João VI. Other artists involved were: Félix Taunay with four landscapes of Rio de Janeiro; Simplício de Sá with several portraits; Cristo Moreira with historic figures, ships and landscapes; Francisco de Sousa Lobo with portraits and historical figures; José dos Reis Carvalho, with ships and still life portraits; Afonso Falcoz with the human figure and portraits; João Clímaco with sketches; and Augusto Goulart with anatomical sketches.

Second exhibition

Thanks to the efforts of Debret and Araújo Porto-Alegre, a second exposition occurred in 1830. During the eight days that it was open to the public, it had a flood of visitors. In the Painting Section, there were sixty-four pieces from the same artists as the first exposition and a few new people—including Henrique José da Silva (painter), Domingos José Gonçalves Magalhães, Antônio Pinheiro de Aguiar, Marcos José Pereira, Correia de Lima, Frederico Guilherme Briggs, Jó Justino de Alcântara, and Joaquim Lopes de Barros Cabral.

Second reign era

In 1831, the structure of the school already necessitated renovations, which were introduced by the so-called Lino-Coutinho Reform implemented by decree in 1833. This decree reformulated the statutes and, among other things, systematized the granting of distinguished honors and awards. [14] The reform also established a traditional academic system at the school, which was defined by the emulation of masters, the copying of famous works, and the mastery of basic tools of the trade. [15]

In 1834, Félix Taunay assumed the directorship of the AIBA. Taunay was the son of one of the members of The French Mission. Despite this connection, he did little to try and re-establish the vocational technical courses which were originally part of the curriculum. [13] On the other hand, he reinforced the teaching model inspired by European academics and, for him, the only way to introduce Brazilians to the "civilized" world of art was through European imitation. To accomplish this, Taunay acquired significant collections of sketches and sculptures for the students at the Academy to study. Included in these collections were the copies of several celebrated pieces, adding to the didactic resources initially gathered by Lebreton and Dom João. Taunay also created a scholarship in 1845 for Brazilian artists at the Academy to study in Europe. The award was intended to help students perfect their craft under the tutelage of important professors and world-famous masters. [15] [16] Some of his other contributions include: turning the school's General Exhibitions into public events, fighting for the Academy's participation as a consultant on official government projects, and organizing the school's library, which included translating books to facilitate study of neoclassical concepts by Brazilian students who had little previous instruction. [5]

Despite constantly facing difficulties, in the second half of the nineteenth century the Imperial Academy reached its golden age under the dynamic (but brief) leadership of Araújo Porto-Alegre. As the impact of the Industrial Revolution spread across the globe, interest in vocational and technical trades experienced a rebirth because they were seen as an important part of Brazil's modernization process. [15] After assuming his post in 1854, Porto-Alegre championed the 'Reforma Pedreira' (Quarry Reform). He left his progressive and reformist intentions clear, stating:

- "I did not come here with unfounded desires, or with the vanity to ostentatiously create public expositions in a new country in which the rich and the aristocratic still do not recognize the fine arts and instead adorn themselves with their coat of arms and their acts of charity. We all know that artistic exhibitions only shine in countries that invest in original statues and paintings, and where architects are continuously planning buildings that become part of the public space. We all know that only Their Majesties buy pieces of art at exhibitions…Our mission will be of a more modest order that is more useful and necessary in reality…before the artist can create, he must first become an artisan.". [17]

- "The new classes that the Imperial Government offers (…) will reform the instruction of our youth and begin a new era of Brazilian industry. It will give the youth an honest and stable livelihood. Through them, apprentices will receive an opportunity, denied for thirty years by those that lived off of their sweat. This will pay back a portion of the debt incurred in Ipiranga; because a nation is only independent when it values intellectual production, when it is content in its own identity, and when it fosters a sense of national consciousness. In doing so, it steps out of a tumultuous arena in which internal and external contradictions are debated to occupy itself with material progress based in morality. These new classes will have a rich future and a new vision for the study of nature and for an admiration of its infinite varieties and forms. (…) Young people, turn away from government jobs that will age you prematurely, trap you in a life of poverty, and enslave you. Apply yourselves in the arts and industries: the arm that was born to plane or wield a trowel should not hold a pen. Banish your prejudices about decadence, laziness and corruption: the artist and the tradesman are building the fatherland, equal to the priest, the magistrate, and the soldier. The work requires strength, intelligence, and the power to channel the divine". [18]

The "Quarry Reform" rebuilt much of Lebreton's original project, in relation to the valorization of technical courses and a curriculum as broad as it was profound for Academy students. As a result, the school began offering courses in decorative drawing and sculpture, geometric design, art history and theory, aesthetics, archaeology, industrial design, and applied mathematics. A curriculum for night classes was also created for trade apprentices, focusing on industrial design, light and perspective, decorative drawing and sculpting, drawing the human body with live models, and elementary mathematics. [13] Porto-Alegre fez mais pela escola: construiu uma nova biblioteca, construiu e decorou a pinacoteca, lutou por melhorias e ampliação da sede da Academia, iniciou a restauração dos quadros da coleção didática e propôs a realização de debates e estudos sobre temas relevantes para o amadurecimento de uma arte condizente com a realidade brasileira. [5]

Above all, the normative influence of the Academy was reinforced through the national production of art. The Academy was responsible for any and all artistic projects financed by the State, for which they put strict rules and methodologies in place and oversaw compliance. This high level of control, which seemed excessive and unnecessary to some, generated new controversy and resistance. Principally, conflict surrounded the copying requirement within the artistic curriculum. On the other hand, from that moment on the AIBA ceased being a simple preparatory center for artists and became actively engaged in the creation of a national identity consistent with the modernizing project of Dom Pedro II. Dom Pedro III was the greatest patron of the period and his personal income provided resources for the functioning of the school. [15] [19]

Rise and fall of an institution

The Academy eventually consolidated itself, with alumni becoming teachers and foreigners attracted into its circle, which stimulated cultural life in Rio de Janeiro and, by extension, throughout the Empire. Among its many artistic specialties, historically-themed paintings became the most popular during this period; followed only by official portraits, landscapes and still-life pieces. This hierarchy of subjects was directly connected to the moral and educational preferences of Academic art. In terms of style, Neoclassicism remained influential but Romanticism came to dominate artistic tendencies. Romanticism, imported from Europe, evolved into a more optimistic and less morbid version, known as Ultra-Romanticism in Brazil. This synthesis made the style more eclectic and appropriate to the historical moment. Artists, often commissioned directly by the government, produced a series of grandiose works, especially in painting, intended to visually portray a civilized and heroic past comparable to that of Europe. African slaves and people of color were ignored and generally relegated to anonymous figures in artwork from this period. In contrast, Native Brazilians received considerable representation in historic paintings as idealized figures. [5] [15]

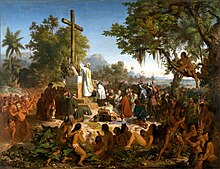

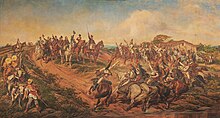

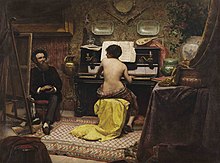

The most outstanding results of this cultural revolution centered at the AIBA appeared in the last two decades of the Empire through the work of Victor Meirelles, Pedro Américo, and, soon after, Almeida Júnior, Rodolfo Bernardelli, and Rodolfo Amoedo who formed part of the landscape group following in the footsteps of German Georg Grimm. Among the large number of artists during this period, Meirelles and Américo were the greatest of their generation, creating pieces that form part of collective national memory even today. Some of the many classic works include: A Primeira Missa no Brasil (1861), Batalha de Guararapes (1879), Combate Naval do Riachuelo (1882–83), Moema (1866), A Fala do Trono (1872), A Batalha do Avaí (1877), O Grito do Ipiranga (1888), and Tiradentes Esquartejado (1893). [5] Lesser known, though significant, works include: O Último Tamoio (1883), O Derrubador Brasileiro (1879), O Descanso do Modelo (1882), Caipira Picando Fumo (1893), and O Violeiro (1899).

At the same time that the Academy solidified its ascendancy within the Brazilian artistic community, it began to be heavily criticized. The basis of this criticism evolved from the changing tastes at the end of the 19th century, a period in which new aesthetics and themes were being absorbed by the bourgeoisie public. This educated group filled official artistic discourse, though they were considered backward and elitist. Angelo Agostini ignited controversy in 1870 over national identity and the support of alternate artistic practices, as defended by George Grimm and his group. Gonzaga Duque was another critic who wrote during the same period. Duque denounced what he saw as the distancing of Brazil from its culture and the lack of originality of the followers of the old masters, calling them talentless imitators. [20]

The Republican period

With the proclamation of the Republic, the old imperial Academy was converted into the "National School for the Fine Arts", under the direction of Rodolfo Bernardelli, who was already a professor of sculpture and artist laureate and highly respected by many influential members of the intellegencia. However, he was a controversial figure and an administrator amidst accusations of partisanship and incompetence. The problems continued to worsen, resulting in the end of classes and the erasure of illustrious names, like Victor Meirelles, from the official roster along with the names of several notable alumni. The professors revolted and signed a motion against him, calling his administration a disaster. [21] Under pressure, Bernardelli stepped down in 1915. The school survived for a few more years, easing their technical requirements and permitting the increased participation of women. The school also faced the appearance of various aesthetic trends in rapid succession, including Symbolism, Impressionism, Expressionism, and Art Nouveau. [22] [23]

As higher education was being re-shaped in Brazil, the school was absorbed by UFRJ in 1931 which signified the end of one system and the beginning of another dominated by Modernism. The principles of modernism combated the predictable and routine aspects of artistic practices along with methodical, disciplined curriculums; they instead emphasized creative spontaneity and individual genius. [24] Despite criticism, the Academy's traditional model inspired the structures used by art schools across Brazil, like the Liceu de Artes e Ofícios do Rio de Janeiro (1856), the Liceu de Artes e Ofícios de São Paulo (1873), and the Liceu Nóbrega de Artes e Ofícios in Pernambuco (1880). It also influenced the curriculum of arts programs at several universities, particularly the Instituto de Artes da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (1908). The widespread adoption of the Academy's values proved its efficiency and capacity for adaptation and innovation. [13] [25]

References

- ^ a b Denis, Rafael Cardoso. "Academicism, Imperialism and national identity: the case of Brazil's Academia Imperial de Belas Artes", In: Denis, Rafael Cardoso; Trod, Colin. Art and the academy in the nineteenth century. Manchester University Press, 2000. pp. 55–56

- ^ Pinassi, Maria Orlanda. Três devotos, uma fé, nenhum milagre: Nitheroy, revista brasiliense de ciências, letras e artes. Coleção Prismas. UNESP, 1998, pp. 55–59

- ^ Schwarcz, Lilia Moritz. O sol do Brasil: Nicolas-Antoine Taunay e as desventuras dos artistas franceses na corte de d. João. Companhia das Letras, 2008, pp. 176–188

- ^ a b c Neves, Lúcia M. B. Pereira das. A missão artística francesa Archived 10 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Rede da Memória Virtual Brasileira.

- ^ a b c d e f Fernandes, Cybele Vidal Neto. "O Ensino de Pintura e Escultura na Academia Imperial das Belas Artes" In: 19&20, Rio de Janeiro, v. II, n. 3, jul. 2007

- ^ a b Lebreton, Joachim. Memória do Cavaleiro Joachim Lebreton para o estabelecimento da Escola de Belas Artes, no Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro, 12 de junho de 1816.

- ^ Schwarcz, pp. 189–193

- ^ a b Siqueira, Vera Beatriz. "Redescobrir o Rio de Janeiro". In: 19&20 – A revista eletrônica de DezenoveVinte. Volume I, no 3, novembro de 2006.

- ^ Freire, Laudelino. Um Século de Pintura (1816–1916). Disponível em Pitoresco.com

- ^ Schwarcz, pp. 233–234

- ^ Mattos, Adalberto "O Salão de MCMXXIV. Pintura, Escultura, Arquitetura, Gravura". In: Illustração Brasileira, ano V, n. 48, ago. 1924, s/p

- ^ Almeida, Bernardo Domingos de. "Portal da antiga Academia Imperial de Belas Artes: A entrada do Neoclassicismo no Brasil". In: 19&20. Rio de Janeiro, v. III, n. 1, jan. 2008

- ^ a b c d Cardoso, Rafael. "A Academia Imperial de Belas Artes e o Ensino Técnico". In: 19&20 – A revista eletrônica de DezenoveVinte. Volume III, n. 1, janeiro de 2008.

- ^ Decretos e Regulamentações. Disponível em 19&20

- ^ a b c d e Leite, Reginaldo da Rocha. "A Contribuição das Escolas Artísticas Européias no Ensino das Artes no Brasil Oitocentista". In: 19&20, Rio de Janeiro, v. IV, n. 1, jan. 2009

- ^ Leite, Reginaldo da Rocha. "A Pintura de Temática Religiosa na Academia Imperial das Belas Artes: Uma Abordagem Contemporânea". 19&20, Rio de Janeiro, v. II, n. 1, jan. 2007

- ^ Migliaccio, Luciano. "O Século XIX". In: Aguilar, Nelson. Mostra do Redescobrimento: Arte do Século XIX. São Paulo: Fundação Bienal de São Paulo; Associação Brasil 500 Anos Artes Visuais, 2000. p. 201

- ^ Ferrari, Paula (org.). Manoel de Araujo Porto-Alegre: Discurso pronunciado na Academia das Belas Artes em 1855, por ocasião do estabelecimento das auras de matemáticas, estéticas, etc.. In: 19&20. Rio de Janeiro, v. III, n. 4, out. 2008

- ^ Biscardi, Afrânio & Rocha, Frederico Almeida. "O Mecenato Artístico de D. Pedro II e o Projeto Imperial". In: 19&20 – A revista eletrônica de DezenoveVinte. Volume I, n. 1, maio de 2006

- ^ Quírico, Tamara. "Comentários e críticas de Gonzaga Duque a Pedro Américo". In: 19&20. Rio de Janeiro, v. I, n. 1, mai. 2006

- ^ Weisz, Suely de Godoy. "Rodolpho Bernardelli, um perfil do homem e do artista segundo a visão de seus contemporâneos". In: 19&20 – A revista eletrônica de DezenoveVinte. Rio de Janeiro, v. II, n. 4, out. 2007

- ^ Valle, Arthur. "Pensionistas da Escola Nacional de Belas Artes na Academia Julian (Paris) durante a 1ª República (1890–1930)". In: 19&20. Rio de Janeiro, v. I, n. 3, nov. 2006

- ^ Marques-Samyn, Henrique. MARQUES-SAMYN "O direito da mulher às artes" Archived 1 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Resenha de Simioni, Ana Paula Cavalcanti, In: Profissão artista: pintoras e escutoras acadêmicas brasileiras. Edusp/Fapesp, 2008

- ^ Eulálio Alexandre. "O Século XIX". In: Tradição e Ruptura. Síntese de Arte e Cultura Brasileiras. São Paulo: Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, 1984–85, p. 121

- ^ Simon, Círio. Origens do Instituto de Artes da UFRGS. Porto Alegre: PUC-RS, 2006