4-point player is a disability sport classification for wheelchair basketball. Players in this class have normal trunk function but have a reduced level of functioning in one or both of their lower limbs. They may have difficulty with sideways movements. People in this class include ISOD classified A1, A2 and A3 players.

Because of their high point number, players in this class may see fewer minutes than lower-point players. Their increased functionality means they can move faster on the court then lower-point players. This means they can pick up a lot more rebounds but are also prone to having more turnovers.

The class includes people with amputations. Amputees are put into this class depending on the length of their stumps and if they play using prosthetic legs. Classification into this classes has four phases. They are a medical assessment, observation during training, observation during competition and assessment. Observation during training may include a game of one on one. Once put into this class, it is very difficult to be classified out of it.

People in this class include Australia's Cobi Crispin, Bridie Kean, Liesl Tesch and Leanne Del Toso.

Definition

This classification is for wheelchair basketball. [1] Classification for the sport is done by the International Wheelchair Basketball Federation. [2] Classification is extremely important in wheelchair basketball because when players point totals are added together, they cannot exceed fourteen points per team on the court at any time. [3] Jane Buckley, writing for the Sporting Wheelies, describes the wheelchair basketball players in this classification as players having: "Normal trunk movement but some reduced lower limb function as they unable to lean to both sides with full control." [1] The Australian Paralympic Committee defines this classification as: "Players with normal trunk movement, but usually due to limitations in one lower limb they have difficulty with controlled sideways movement to one side." [4] The International Wheelchair Basketball Federation defines a 4-point player as "Normal trunk movement, but usually due to limitations in one lower limb they have difficulty with controlled sideways movement to one side." [5] The Cardiff Celts, a wheelchair basketball team in Wales, explain this classification as, "able to move the trunk forcefully in the direction of the follow-through after shooting. Class 4 players are able to flex, extend and rotate the trunk maximally while performing both one-handed and two-handed passes and can lean forward and to at least one side to grasp an over-the-head rebound with both hands. Class 4 players are able to push and stop the wheelchair with rapid acceleration and maximal forward movement of the trunk. Typical Class 4 Disabilities include : L5-S1 paraplegia, with control of hip abduction and extension movements on at least one side. Post-polio paralysis with one leg involvement. Hemipelvectomy. Single above- knee amputees with short residual limbs. Most double above-knee amputees. Some double below-knee amputees." [6]

Strategy and on court ability

4-point players and 4.5-point players receive less playing time than 1-point players because of their higher point value. [7] 4-point players can move their wheelchairs at a significantly faster speed than 1-point players. [8] There is a significant difference in special endurance between 2-point players, and 3- and 4-point players, with 2-point players having less special endurance. [8] In games, 4-point players steal the ball three times more often than 1-point players. [8] 4-point players generally have the greatest number of rebounds on the court because of competitive advantage when under the basket in terms of height, stability and strength. [8] 4-point players turn over the ball with much greater frequency than 1-point players. [8]

Disability groups

Amputees

People with amputations may compete in this class. This includes A1, A2, A3, A4 and A9 ISOD classified players. [9] Because of the potential for balance issues related to having an amputation, during weight training, amputees are encouraged to use a spotter when lifting more than 15 pounds (6.8 kg). [10]

Lower limb amputees

ISOD classified A1 players may be found in this class. [11] This ISOD class is for people who have both legs amputated above the knee. [10] There is a lot of variation though in which IWBF class these players may be put into. Those with hip articulations are generally classified as 3-point players, while those with slightly longer leg stumps in this class are 3.5-point players. Those above the knee amputees with the longest stumps who use prosthetic legs may be classified as 4-point players. [11] Lower limb amputations effect a person's energy cost for being mobile. To keep their oxygen consumption rate similar to people without lower limb amputations, they need to walk slower. [12] A1 basketball players use around 120% more oxygen to walk or run the same distance as someone without a lower limb amputation. [12]

ISOD classified A2 players can be classified a 4-point players, especially if the amputation type is a hip disarticulation. A2 players can have issues with controlling their sideways movements. [13] [14] A2 players use around 87% more oxygen to walk or run the same distance as someone without a lower limb amputation. [12]

ISOD classified A3 tend to be classified a 4-point players or 4.5-point players, though they could also be classified as 3.5-point players. The cutoff point between the three classes is generally based on the location of the amputations. People with amputations longer than 2/3rds the length of their thigh are generally 4.5-point players. Those with shorter amputations are 4-point players. [13] [15] A3 players use around 41% more oxygen to walk or run the same distance as someone without a lower limb amputation. [12] Players in this class can have issues with controlling their sideways movements. [13]

ISOD classified A4 tend to be classified a 4-point players or 4.5-point players. The cutoff point between the two classes is generally based on the location of the amputations. People with amputations longer than 2/3rds the length of their thigh are generally 4.5-point players. Those with shorter amputations are 4-point players. [13] [16] A4 basketball players use around 7% more oxygen to walk or run the same distance as someone without a lower limb amputation. [12]

Upper and lower limb amputees

ISOD classified A9 players may be found in this class. [17] The class they play in will be specific to the location of their amputations and their lengths. Players with hip disarticulation in both legs are 3.0 point players while players with two slightly longer above the knee amputations are 3.5-point players. Players with one hip disarticulation may be 3.5-point players or 4-point players. People with amputations longer than 2/3rds the length of their thigh when wearing a prosthesis are generally 4.5-point players. Those with shorter amputations are 4-point players. At this point, the classification system for people in this class then considers the nature of the hand amputation by subtracting points to assign a person to a class. A wrist disarticulation moves a player down a point class, while a pair of hand amputations moves a player down two-point classes, with players with upper limb amputations ending up as low as a 1-point player. [18]

Spinal cord injuries

People with spinal cord injuries compete in this class, including F6 or F7 sportspeople. [19] [20]

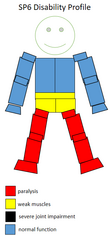

F6

This is wheelchair sport classification that corresponds to the neurological level L2 - L5. [21] [22] Historically, this class has been known as Lower 4, Upper 5. [21] [22] The location of lesions on different vertebrae tend to be associated with disability levels and functionality issues. L2 is associated with hip flexors. L3 is associated with knee extensors. L4 is associated with ankle doris flexors. L5 is associated with long toe extensors. [23] People with lesions at L4 have issues with their lower back muscles, hip flexors and their quadriceps. [24] People with lesions at the L4 to S2 who are complete paraplegics may have motor function issues in their gluts and hamstrings. Their quadriceps are likely to be unaffected. They may be absent sensation below the knees and in the groin area. [25] People with lesions at L4 have trunk stability, can lift a leg and can flex their hips. They can walk independently with the use of longer leg braces. They may use a wheelchair for the sake of convenience. Recommended sports include many standing related sports. [24] People in this class have a total respiratory capacity of 88% compared to people without a disability. [26]

The original wheelchair basketball classification system in 1966 had 5 classes: A, B, C, D, S. Each class was worth so many points. A was worth 1, B and C were worth 2. D and S were worth 3 points. A team could have a maximum of 12 points on the floor. This system was the one in place for the 1968 Summer Paralympics. Class A was for T1-T9 complete. Class B was for T1-T9 incomplete. Class C was for T10-L2 complete. Class D was for T10-L2 incomplete. Class S was for Cauda equina paralysis. [19] This class would have been part of Class C or Class D. [19]

From 1969 to 1973, a classification system designed by Australian Dr. Bedwell was used. This system used some muscle testing to determine which class incomplete paraplegics should be classified in. It used a point system based on the ISMGF classification system. Class IA, IB and IC were worth 1 point. Class II for people with lesions between T1-T5 and no balance were also worth 1 point. Class III for people with lesions at T6-T10 and have fair balance were worth 1 point. Class IV was for people with lesions at T11-L3 and good trunk muscles. They were worth 2 points. Class V was for people with lesions at L4 to L5 with good leg muscles. Class IV was for people with lesions at S1-S4 with good leg muscles. Class V and IV were worth 3 points. The Daniels/Worthington muscle test was used to determine who was in class V and who was class IV. Paraplegics with 61 to 80 points on this scale were not eligible. A team could have a maximum of 11 points on the floor. The system was designed to keep out people with less severe spinal cord injuries, and had no medical basis in many cases. [27] This class would have been IV or V. [27]

In 1982, wheelchair basketball finally made the move to a functional classification system internationally. While the traditional medical system of where a spinal cord injury was located could be part of classification, it was only one advisory component. With this system, players in this class became Class II and 3- or 3.5-point players. A maximum of 14 points was allowed on the court at a time. Under the current system, they would likely be classified a 3-point player. if they are L2 to L4. They are likely to be classified a 4-point player if they are L5 to S2. [20]

F7

F7 is wheelchair sport classification, that corresponds to the neurological level S1- S2. [21] [28] The location of lesions on different vertebrae tend to be associated with disability levels and functionality issues. S1 is associated with ankle plantar flexors. [29] People with a lesion at S1 have their hamstring and peroneal muscles affected. Functionally, they can bend their knees and lift their feet. They can walk on their own, though they may require ankle braces or orthopedic shoes. They can generally change in any physical activity. [24] People with lesions at the L4 to S2 who are complete paraplegics may have motor function issues in their glutes and hamstrings. Their quadriceps are likely to be unaffected. They may be absent sensation below the knees and in the groin area. [25]

Wheelchair basketball was one of the earliest sports available to people in this class. From 1969 to 1973, players in this class would have been V. [19] Under the system that went into place starting in 1982, players in this class would have been 4- or 4.5-point players. [19] Under the current classification system, they would likely be classified as a 4-point player. [20]

History

The original classification system for wheelchair basketball was a 3 class medical one managed by ISMGF. Players in this system were class 3. Following the move to the functional classification system in 1983, class 3 players became class 4 players. The change also allowed amputee players to be part of this class, and they came to be some of the most dominant players in it. [30]

The classification was created by the International Paralympic Committee and has roots in a 2003 attempt to address "the overall objective to support and coordinate the ongoing development of accurate, reliable, consistent and credible sport focused classification systems and their implementation." [31]

Wheelchair basketball players who went to compete at the 2012 Summer Paralympics in this classification need to have their classification be in compliance with the system organised by the IWBF and their status being listed as ‘Review’ or ‘Confirmed’. [32] For the 2016 Summer Paralympics in Rio, the International Paralympic Committee had a zero classification at the Games policy. This policy was put into place in 2014, with the goal of avoiding last minute changes in classes that would negatively impact athlete training preparations. All competitors needed to be internationally classified with their classification status confirmed prior to the Games, with exceptions to this policy being dealt with on a case-by-case basis. [33] In case there was a need for classification or reclassification at the Games despite best efforts otherwise, wheelchair basketball classification was scheduled for September 4 to 6 at Carioca Arena 1. [33]

Getting classified

Classification generally has four phases. The first stage of classification is a health examination. For amputees in this class, this is often done on site at a sports training facility or competition. The second stage is observation in practice, the third stage is observation in competition and the last stage is assigning the sportsperson to a relevant class. [34] Sometimes the health examination may not be done on site for amputees because the nature of the amputation could cause not physically visible alterations to the body. This is especially true for lower limb amputees as it relates to how their limbs align with their hips and the impact this has on their spine and how their skull sits on their spine. [35] For wheelchair basketball, part of the classification process involves observing a player during practice or training. This often includes observing them go one on one against someone who is likely to be in the same class the player would be classified into. [36] Once a player is classified, it is very hard to be classified into a different classification. Players have been known to have issues with classification because some players play down their abilities during the classification process. At the same time, as players improve at the game, movements become regular and their skill level improves. This can make it appear like their classification was incorrect. [7]

In Australia, wheelchair basketball players and other disability athletes are generally classified after they have been assessed based on medical, visual or cognitive testing, after a demonstration of their ability to play their sport, and the classifiers watching the player during competitive play. [37]

Competitors

Australian Brett Stibners is a 4-point player. [38] Cobi Crispin, Bridie Kean, Liesl Tesch and Leanne Del Toso are 4-point players for Australia's women's national team. [39] Adam Lancia is a 4-point player for the Canadian men's national team. [40]

Variants

Wheelchair Twin Basketball is a major variant of wheelchair basketball aimed at tetraplegic players, who are typically more impaired than a wheelchair basketball 1-point player. [41] This version is supported by the International Stoke Mandeville Wheelchair Sports Federation, [41] and played in Japan. [42] Twin basketball has a three-point classification system based on the evaluation of the mobility of people with cervical spinal cord injuries. In this variant, the equivalent to 4-point players would be players without a head band who "possess good triceps, a good balance of the hand and some finger functions. They can score by shooting with a smaller and lighter basketball to the normal basket." [41]

References

- ^ a b Buckley, Jane (2011). "Understanding Classification: A Guide to the Classification Systems used in Paralympic Sports". Archived from the original on 11 April 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- ^ "IPC CLASSIFICATION CODE AND INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee. November 2007. p. 21. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- ^ "Wheelchair Basketball". International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- ^ "Classification Information Sheet: Wheelchair Basketball" (PDF). Sydney, Australia: Australian Paralympic Committee. 1 July 2013. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ "International Wheelchair Basketball Federation Functional Player Classification System" (PDF). International Wheelchair Basketball Federation. December 2004. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- ^ "Simplified Rules of Wheelchair Basketball and a Brief Guide to the Classification system". Cardiff Celts. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ a b Berger, Ronald J. (March 2009). Hoop dreams on wheels: disability and the competitive wheelchair athlete. Routledge. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-415-96509-5.

- ^ a b c d e Doll-Tepper, Gudrun; Kröner, Michael; Sonnenschein, Werner; International Paralympic Committee, Sport Science Committee (2001). "Organisation and Administration of the Classification Process for the Paralympics". New Horizons in sport for athletes with a disability : proceedings of the International VISTA '99 Conference, Cologne, Germany, 28 August-1 September 1999. Vol. 1. Oxford (UK): Meyer & Meyer Sport. pp. 355–368. ISBN 1841260363. OCLC 48404898.

- ^ DE PASQUALE, DANIELA (2009–2010). "VALUTAZIONE FUNZIONALE DELLE CAPACITA' FISICHE NEL GIOCATORE DI BASKET IN CARROZZINA D'ALTO LIVELLO" [FUNCTIONAL EVALUATION OF THE CAPACITY 'PHYSICAL IN WHEELCHAIR BASKETBALL PLAYER OF HIGH LEVEL] (PDF). Thesis: UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI ROMA (in Italian).

- ^ a b "Classification 101". Blaze Sports. Blaze Sports. June 2012. Archived from the original on August 16, 2016. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- ^ a b DE PASQUALE, DANIELA (2009–2010). "VALUTAZIONE FUNZIONALE DELLE CAPACITA' FISICHE NEL GIOCATORE DI BASKET IN CARROZZINA D'ALTO LIVELLO" [FUNCTIONAL EVALUATION OF THE CAPACITY 'PHYSICAL IN WHEELCHAIR BASKETBALL PLAYER OF HIGH LEVEL] (PDF). Thesis: UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI ROMA (in Italian).

- ^ a b c d e Miller, Mark D.; Thompson, Stephen R. (2014-04-04). DeLee & Drez's Orthopaedic Sports Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9781455742219.

- ^ a b c d Bressan, ES (2008). "Striving for fairness in Paralympic sport-Support from applied sport science". Continuing Medical Education.

- ^ DE PASQUALE, DANIELA (2009–2010). "VALUTAZIONE FUNZIONALE DELLE CAPACITA' FISICHE NEL GIOCATORE DI BASKET IN CARROZZINA D'ALTO LIVELLO" [FUNCTIONAL EVALUATION OF THE CAPACITY 'PHYSICAL IN WHEELCHAIR BASKETBALL PLAYER OF HIGH LEVEL] (PDF). Thesis: UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI ROMA (in Italian).

- ^ DE PASQUALE, DANIELA (2009–2010). "VALUTAZIONE FUNZIONALE DELLE CAPACITA' FISICHE NEL GIOCATORE DI BASKET IN CARROZZINA D'ALTO LIVELLO" [FUNCTIONAL EVALUATION OF THE CAPACITY 'PHYSICAL IN WHEELCHAIR BASKETBALL PLAYER OF HIGH LEVEL] (PDF). Thesis: UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI ROMA (in Italian).

- ^ DE PASQUALE, DANIELA (2009–2010). "VALUTAZIONE FUNZIONALE DELLE CAPACITA' FISICHE NEL GIOCATORE DI BASKET IN CARROZZINA D'ALTO LIVELLO" [FUNCTIONAL EVALUATION OF THE CAPACITY 'PHYSICAL IN WHEELCHAIR BASKETBALL PLAYER OF HIGH LEVEL] (PDF). Thesis: UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI ROMA (in Italian).

- ^ DE PASQUALE, DANIELA (2009–2010). "VALUTAZIONE FUNZIONALE DELLE CAPACITA' FISICHE NEL GIOCATORE DI BASKET IN CARROZZINA D'ALTO LIVELLO" [FUNCTIONAL EVALUATION OF THE CAPACITY 'PHYSICAL IN WHEELCHAIR BASKETBALL PLAYER OF HIGH LEVEL] (PDF). Thesis: UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI ROMA (in Italian).

- ^ DE PASQUALE, DANIELA (2009–2010). "VALUTAZIONE FUNZIONALE DELLE CAPACITA' FISICHE NEL GIOCATORE DI BASKET IN CARROZZINA D'ALTO LIVELLO" [FUNCTIONAL EVALUATION OF THE CAPACITY 'PHYSICAL IN WHEELCHAIR BASKETBALL PLAYER OF HIGH LEVEL] (PDF). Thesis: UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI ROMA (in Italian).

- ^ a b c d e Thiboutot, Armand; Craven, Philip (1996). The 50th Anniversary of Wheelchair Basketball. Waxmann Verlag. ISBN 9783830954415.

- ^ a b c "Simplified Rules of Wheelchair Basketball and a Brief Guide to the Classification system". Cardiff Celts. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ a b c National Governing Body for Athletics of Wheelchair Sports, USA. Chapter 2: Competition Rules for Athletics. United States: Wheelchair Sports, USA. 2003.

- ^ a b Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in European Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- ^ International Paralympic Committee (February 2005). "SWIMMING CLASSIFICATION CLASSIFICATION MANUAL" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee Classification Manual. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04.

- ^ a b c Winnick, Joseph P. (2011-01-01). Adapted Physical Education and Sport. Human Kinetics. ISBN 9780736089180.

- ^ a b Goosey-Tolfrey, Vicky (2010-01-01). Wheelchair Sport: A Complete Guide for Athletes, Coaches, and Teachers. Human Kinetics. ISBN 9780736086769.

- ^ Woude, Luc H. V.; Hoekstra, F.; Groot, S. De; Bijker, K. E.; Dekker, R. (2010-01-01). Rehabilitation: Mobility, Exercise, and Sports : 4th International State-of-the-Art Congress. IOS Press. ISBN 9781607500803.

- ^ a b Chapter 4. 4 - Position Statement on background and scientific rationale for classification in Paralympic sport (PDF). International Paralympic Committee. December 2009.

- ^ Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in European Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- ^ International Paralympic Committee (February 2005). "SWIMMING CLASSIFICATION CLASSIFICATION MANUAL" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee Classification Manual. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04.

- ^ Labanowich, Stan; Thiboutot, Armand (2011-01-01). Wheelchairs can jump!: a history of wheelchair basketball : tracing 65 years of extraordinary Paralympic and World Championship performances. Boston, MA.: Acanthus Publishing. ISBN 9780984217397. OCLC 792945375.

-

^ "Paralympic Classification Today". International Paralympic Committee. 22 April 2010: 3.

{{ cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=( help) - ^ "Wheelchair Basketball: LONDON 2012 PARALYMPIC GAMES" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Rio 2016 Classification Guide" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee. International Paralympic Committee. March 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- ^ Tweedy, Sean M.; Beckman, Emma M.; Connick, Mark J. (August 2014). "Paralympic Classification: Conceptual Basis, Current Methods, and Research Update". Paralympic Sports Medicine and Science. 6 (85): S11-7. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2014.04.013. PMID 25134747. S2CID 207403462. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ^ Gilbert, Keith; Schantz, Otto J.; Schantz, Otto (2008-01-01). The Paralympic Games: Empowerment Or Side Show?. Meyer & Meyer Verlag. ISBN 9781841262659.

- ^ DE PASQUALE, DANIELA (2009–2010). "VALUTAZIONE FUNZIONALE DELLE CAPACITA' FISICHE NEL GIOCATORE DI BASKET IN CARROZZINA D'ALTO LIVELLO" [FUNCTIONAL EVALUATION OF THE CAPACITY 'PHYSICAL IN WHEELCHAIR BASKETBALL PLAYER OF HIGH LEVEL] (PDF). Thesis: UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI ROMA (in Italian).

- ^ "Understanding Classification". Sydney, Australia: Australian Paralympic Committee. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- ^ "Brett Stibners". Basketball Australia. Archived from the original on 13 April 2012. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ "2010 WC Team". Basketball Australia. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- ^ "Team Canada: Men's Roster". Canada: Wheelchair Basketball Canada. 2011. Archived from the original on 22 May 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- ^ a b c Strohkendl, Horst (2002). "WHEELCHAIR TWIN BASKETBALL... an explanation" (PDF). International Stoke Mandeville Wheelchair Sports Federation. pp. 9–10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ IWAYA, TSUTOMU. "INSTRUCTION MANUAL FOR TWIN BASKETBALL GAMES - FOR PEOPLE WITH CERVICAL CORD INJURIES" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2011.