| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

|

Preferred IUPAC name

2-(1H-Indol-3-yl)ethan-1-amine | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (

JSmol)

|

|

| 125513 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.464 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem

CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (

EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties [1] | |

| C10H12N2 | |

| Molar mass | 160.220 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | white to orange needles |

| Melting point | 118˚C |

| Boiling point | 137 °C (279 °F; 410 K) (0.15 mmHg) |

| negligible solubility in water | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their

standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

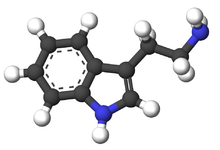

Tryptamine is an indolamine metabolite of the essential amino acid, tryptophan. [2] [3] The chemical structure is defined by an indole—a fused benzene and pyrrole ring, and a 2-aminoethyl group at the second carbon (third aromatic atom, with the first one being the heterocyclic nitrogen). [2] The structure of tryptamine is a shared feature of certain aminergic neuromodulators including melatonin, serotonin, bufotenin and psychedelic derivatives such as dimethyltryptamine (DMT), psilocybin, psilocin and others. [4] [5] [6] Tryptamine has been shown to activate trace amine-associated receptors expressed in the mammalian brain, and regulates the activity of dopaminergic, serotonergic and glutamatergic systems. [7] [8] In the human gut, symbiotic bacteria convert dietary tryptophan to tryptamine, which activates 5-HT4 receptors and regulates gastrointestinal motility. [3] [9] [10] Multiple tryptamine-derived drugs have been developed to treat migraines, while trace amine-associated receptors are being explored as a potential treatment target for neuropsychiatric disorders. [11] [12] [13]

For a list of tryptamine derivatives, see: List of substituted tryptamines.

Natural occurrences

For a list of plants, fungi and animals containing tryptamines, see List of psychoactive plants and List of naturally occurring tryptamines.

Mammalian brain

Endogenous levels of tryptamine in the mammalian brain are less than 100 ng per gram of tissue. [14] [15] However, elevated levels of trace amines have been observed in patients with certain neuropsychiatric disorders taking medications, such as bipolar depression and schizophrenia. [16]

Mammalian gut microbiome

Tryptamine is relatively abundant in the gut and feces of humans and rodents. [17] [18] Commensal bacteria, including Ruminococcus gnavus and Clostridium sporogenes in the gastrointestinal tract, possess the enzyme tryptophan decarboxylase, which aids in the conversion of dietary tryptophan to tryptamine. [17] Tryptamine is a ligand for gut epithelial serotonin type 4 (5-HT4) receptors and regulates gastrointestinal electrolyte balance through colonic secretions. [18]

Metabolism

Biosynthesis

To yield tryptamine in vivo, tryptophan decarboxylase removes the carboxylic acid group on the α-carbon of tryptophan. [19] Synthetic modifications to tryptamine can produce serotonin and melatonin; however, these pathways do not occur naturally as the main pathway for endogenous neurotransmitter synthesis. [20]

Catabolism

Monoamine oxidases A and B are the primary enzymes involved in tryptamine metabolism to produce indole-3-acetaldehyde, however it is unclear which isoform is specific to tryptamine degradation. [21]

Mechanisms of action and biological effects

Neuromodulation

Tryptamine can weakly activate the trace amine-associated receptor, TAAR1 (hTAAR1 in humans). [22] [23] [24] Limited studies have considered tryptamine to be a trace neuromodulator capable of regulating the activity of neuronal cell responses without binding to the associated postsynaptic receptors. [24] [25]

hTAAR1

hTAAR1 is a stimulatory G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) that is weakly expressed in the intracellular compartment of both pre- and postsynaptic neurons. [26] Tryptamine and other hTAAR1 agonists can increase neuronal firing by inhibiting neurotransmitter recycling through cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of the monoamine reuptake transporter. [27] [25] This mechanism increases the amount of neurotransmitter in the synaptic cleft, subsequently increasing postsynaptic receptor binding and neuronal activation. [25] Conversely, when hTAAR1 are colocalized with G protein-coupled inwardly-rectifying potassium channels (GIRKs), receptor activation reduces neuronal firing by facilitating membrane hyperpolarization through the efflux of potassium ions. [25] The balance between the inhibitory and excitatory activity of hTAAR1 activation highlights the role of tryptamine in the regulation of neural activity. [28]

Activation of hTAAR1 is under investigation as a novel treatment for depression, addiction, and schizophrenia. [29] hTAAR1 is primarily expressed in brain structures associated with dopamine systems, such as the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and serotonin systems in the dorsal raphe nuclei (DRN). [29] Additionally, the hTAAR1 gene is localized at 6q23.2 on the human chromosome, which is a susceptibility locus for mood disorders and schizophrenia. [30] Activation of TAAR1 suggests a potential novel treatment for neuropsychiatric disorders, as TAAR1 agonists produce anti-depressive activity, increased cognition, reduced stress and anti-addiction effects. [28] [30]

Gastrointestinal motility

Tryptamine produced by mutualistic bacteria in the human gut activates serotonin GPCRs ubiquitously expressed along the colonic epithelium. [31] Upon tryptamine binding, the activated 5-HT4 receptor undergoes a conformational change which allows its Gs alpha subunit to exchange GDP for GTP, and its liberation from the 5-HT4 receptor and βγ subunit. [31] GTP-bound Gs activates adenylyl cyclase, which catalyzes the conversion of ATP into cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). [31] cAMP opens chloride and potassium ion channels to drive colonic electrolyte secretion and promote intestinal motility. [32] [33]

Pharmacodynamics

| Tryptamine | Human TAAR1 | Mouse TAAR1 | Rat TAAR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 | Ki | EC50 | Ki | EC50 | Ki | |

| Tryptamine | 21 | N/A | 2.7 | 1.4 | 0.41 | 0.13 |

| Serotonin | >50 | N/A | >50 | N/A | 5.2 | N/A |

| Psilocin | >30 | N/A | 2.7 | 17 | 0.92 | 1.4 |

| DMT | >10 | N/A | 1.2 | 3.3 | 1.5 | 22 |

|

EC50 and Ki values are in micromolar (μM).

EC50 reflects the amount

of tryptamine required to elicit 50% of the maximum TAAR1 response. The smaller the Ki value, the stronger the tryptamine binds to the receptor. | ||||||

Tryptamine-based therapeutics

| Drug | Mechanism | Treatment | Effect | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sumatriptan [35] | 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D agonist | Migraine Headaches | Vasoconstriction of brain blood vessels |  |

| Rizatriptan [35] | 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D agonist | Migraine Headaches | Vasoconstriction of brain blood vessels |  |

| Zolmitriptan [35] | 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D agonist | Migraine Headaches | Vasoconstriction of brain blood vessels |  |

| Almotriptan [35] | 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D agonist | Migraine Headaches | Vasoconstriction of brain blood vessels |  |

| Eletriptan [35] | 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D agonist | Migraine Headaches | Vasoconstriction of brain blood vessels |  |

| Frovatriptan [35] | 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D agonist | Migraine Headaches | Vasoconstriction of brain blood vessels |  |

| Naratriptan [35] | 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D agonist | Migraine Headaches | Vasoconstriction of brain blood vessels |  |

See also

- Tryptophan

- Substituted tryptamines

- Trace amines

- Serotonin receptor agonist

- Human trace amine associated receptor 1

- Neuromodulation

References

- ^ Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (85th ed.). CRC Press. p. 3-564. ISBN 978-0-8493-0484-2.

- ^ a b "Tryptamine". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2020-12-01.

- ^ a b Jenkins, Trisha A.; Nguyen, Jason C. D.; Polglaze, Kate E.; Bertrand, Paul P. (2016-01-20). "Influence of Tryptophan and Serotonin on Mood and Cognition with a Possible Role of the Gut-Brain Axis". Nutrients. 8 (1): 56. doi: 10.3390/nu8010056. ISSN 2072-6643. PMC 4728667. PMID 26805875.

- ^ Tylš, Filip; Páleníček, Tomáš; Horáček, Jiří (2014-03-01). "Psilocybin – Summary of knowledge and new perspectives". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 24 (3): 342–356. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.12.006. ISSN 0924-977X. PMID 24444771. S2CID 10758314.

- ^ Tittarelli, Roberta; Mannocchi, Giulio; Pantano, Flaminia; Romolo, Francesco Saverio (2015). "Recreational Use, Analysis and Toxicity of Tryptamines". Current Neuropharmacology. 13 (1): 26–46. doi: 10.2174/1570159X13666141210222409. ISSN 1570-159X. PMC 4462041. PMID 26074742.

- ^ "The Ayahuasca Phenomenon". MAPS. 21 November 2014. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ Khan, Muhammad Zahid; Nawaz, Waqas (2016-10-01). "The emerging roles of human trace amines and human trace amine-associated receptors (hTAARs) in central nervous system". Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 83: 439–449. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.07.002. ISSN 0753-3322. PMID 27424325.

- ^ Berry, Mark D.; Gainetdinov, Raul R.; Hoener, Marius C.; Shahid, Mohammed (2017-12-01). "Pharmacology of human trace amine-associated receptors: Therapeutic opportunities and challenges". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 180: 161–180. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.07.002. ISSN 0163-7258. PMID 28723415. S2CID 207366162.

- ^ Bhattarai, Yogesh; Williams, Brianna B.; Battaglioli, Eric J.; Whitaker, Weston R.; Till, Lisa; Grover, Madhusudan; Linden, David R.; Akiba, Yasutada; Kandimalla, Karunya K.; Zachos, Nicholas C.; Kaunitz, Jonathan D. (2018-06-13). "Gut Microbiota-Produced Tryptamine Activates an Epithelial G-Protein-Coupled Receptor to Increase Colonic Secretion". Cell Host & Microbe. 23 (6): 775–785.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.05.004. ISSN 1931-3128. PMC 6055526. PMID 29902441.

- ^ Field, Michael (2003). "Intestinal ion transport and the pathophysiology of diarrhea". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 111 (7): 931–943. doi: 10.1172/JCI200318326. ISSN 0021-9738. PMC 152597. PMID 12671039.

- ^ "Serotonin Receptor Agonists (Triptans)", LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury, Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2012, PMID 31644023, retrieved 2020-10-15

- ^ "New Compound Related to Psychedelic Ibogaine Could Treat Addiction, Depression". UC Davis. 2020-12-09. Retrieved 2020-12-11.

-

^ ServiceDec. 9, Robert F.

"Chemists re-engineer a psychedelic to treat depression and addiction in rodents". Science | AAAS. Retrieved 2020-12-11.

{{ cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list ( link) - ^ Tittarelli, Roberta; Mannocchi, Giulio; Pantano, Flaminia; Romolo, Francesco Saverio (2015). "Recreational Use, Analysis and Toxicity of Tryptamines". Current Neuropharmacology. 13 (1): 26–46. doi: 10.2174/1570159X13666141210222409. ISSN 1570-159X. PMC 4462041. PMID 26074742.

- ^ Berry, Mark D.; Gainetdinov, Raul R.; Hoener, Marius C.; Shahid, Mohammed (2017-12-01). "Pharmacology of human trace amine-associated receptors: Therapeutic opportunities and challenges". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 180: 161–180. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.07.002. ISSN 0163-7258. PMID 28723415. S2CID 207366162.

- ^ Miller, Gregory M. (2011). "The Emerging Role of Trace Amine Associated Receptor 1 in the Functional Regulation of Monoamine Transporters and Dopaminergic Activity". Journal of Neurochemistry. 116 (2): 164–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x. ISSN 0022-3042. PMC 3005101. PMID 21073468.

- ^ a b Jenkins, Trisha A.; Nguyen, Jason C. D.; Polglaze, Kate E.; Bertrand, Paul P. (2016-01-20). "Influence of Tryptophan and Serotonin on Mood and Cognition with a Possible Role of the Gut-Brain Axis". Nutrients. 8 (1): 56. doi: 10.3390/nu8010056. ISSN 2072-6643. PMC 4728667. PMID 26805875.

- ^ a b Bhattarai, Yogesh; Williams, Brianna B.; Battaglioli, Eric J.; Whitaker, Weston R.; Till, Lisa; Grover, Madhusudan; Linden, David R.; Akiba, Yasutada; Kandimalla, Karunya K.; Zachos, Nicholas C.; Kaunitz, Jonathan D. (2018-06-13). "Gut Microbiota-Produced Tryptamine Activates an Epithelial G-Protein-Coupled Receptor to Increase Colonic Secretion". Cell Host & Microbe. 23 (6): 775–785.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.05.004. ISSN 1931-3128. PMC 6055526. PMID 29902441.

- ^ Tittarelli, Roberta; Mannocchi, Giulio; Pantano, Flaminia; Romolo, Francesco Saverio (2015). "Recreational Use, Analysis and Toxicity of Tryptamines". Current Neuropharmacology. 13 (1): 26–46. doi: 10.2174/1570159X13666141210222409. ISSN 1570-159X. PMC 4462041. PMID 26074742.

- ^ "Serotonin Synthesis and Metabolism". Sigma Aldrich. 2020.

- ^ "MetaCyc L-tryptophan degradation VI (via tryptamine)". biocyc.org. Retrieved 2020-12-11.

- ^ Yu, Ai-Ming; Granvil, Camille P.; Haining, Robert L.; Krausz, Kristopher W.; Corchero, Javier; Küpfer, Adrian; Idle, Jeffrey R.; Gonzalez, Frank J. (2003-02-01). "The Relative Contribution of Monoamine Oxidase and Cytochrome P450 Isozymes to the Metabolic Deamination of the Trace Amine Tryptamine". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 304 (2): 539–546. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.043786. ISSN 0022-3565. PMID 12538805. S2CID 18279145.

- ^ Khan, Muhammad Zahid; Nawaz, Waqas (2016-10-01). "The emerging roles of human trace amines and human trace amine-associated receptors (hTAARs) in central nervous system". Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 83: 439–449. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.07.002. ISSN 0753-3322. PMID 27424325.

- ^ a b Zucchi, R; Chiellini, G; Scanlan, T S; Grandy, D K (2006). "Trace amine-associated receptors and their ligands". British Journal of Pharmacology. 149 (8): 967–978. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706948. ISSN 0007-1188. PMC 2014643. PMID 17088868.

- ^ a b c d Miller, Gregory M. (2011). "The Emerging Role of Trace Amine Associated Receptor 1 in the Functional Regulation of Monoamine Transporters and Dopaminergic Activity". Journal of Neurochemistry. 116 (2): 164–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x. ISSN 0022-3042. PMC 3005101. PMID 21073468.

- ^ Berry, Mark D.; Gainetdinov, Raul R.; Hoener, Marius C.; Shahid, Mohammed (2017-12-01). "Pharmacology of human trace amine-associated receptors: Therapeutic opportunities and challenges". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 180: 161–180. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.07.002. ISSN 0163-7258. PMID 28723415. S2CID 207366162.

- ^ Jing, Li; Li, Jun-Xu (2015-08-15). "Trace amine-associated receptor 1: a promising target for the treatment of psychostimulant addiction". European Journal of Pharmacology. 761: 345–352. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.06.019. ISSN 0014-2999. PMC 4532615. PMID 26092759.

- ^ a b Grandy, David K.; Miller, Gregory M.; Li, Jun-Xu (2016-02-01). ""TAARgeting Addiction" The Alamo Bears Witness to Another Revolution". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 159: 9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.014. ISSN 0376-8716. PMC 4724540. PMID 26644139.

- ^ a b Berry, Mark D.; Gainetdinov, Raul R.; Hoener, Marius C.; Shahid, Mohammed (2017-12-01). "Pharmacology of human trace amine-associated receptors: Therapeutic opportunities and challenges". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 180: 161–180. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.07.002. ISSN 0163-7258. PMID 28723415. S2CID 207366162.

- ^ a b Gainetdinov, Raul R.; Hoener, Marius C.; Berry, Mark D. (2018-07-01). "Trace Amines and Their Receptors". Pharmacological Reviews. 70 (3): 549–620. doi: 10.1124/pr.117.015305. ISSN 0031-6997. PMID 29941461. S2CID 49411553.

- ^ a b c Bhattarai, Yogesh; Williams, Brianna B.; Battaglioli, Eric J.; Whitaker, Weston R.; Till, Lisa; Grover, Madhusudan; Linden, David R.; Akiba, Yasutada; Kandimalla, Karunya K.; Zachos, Nicholas C.; Kaunitz, Jonathan D. (2018-06-13). "Gut Microbiota-Produced Tryptamine Activates an Epithelial G-Protein-Coupled Receptor to Increase Colonic Secretion". Cell Host & Microbe. 23 (6): 775–785.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.05.004. ISSN 1931-3128. PMC 6055526. PMID 29902441.

- ^ Field, Michael (2003). "Intestinal ion transport and the pathophysiology of diarrhea". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 111 (7): 931–943. doi: 10.1172/JCI200318326. ISSN 0021-9738. PMC 152597. PMID 12671039.

- ^ "Microbiome-Lax May Relieve Constipation". GEN - Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News. 2018-06-15. Retrieved 2020-12-11.

- ^ Gainetdinov, Raul R.; Hoener, Marius C.; Berry, Mark D. (2018-07-01). "Trace Amines and Their Receptors". Pharmacological Reviews. 70 (3): 549–620. doi: 10.1124/pr.117.015305. ISSN 0031-6997. PMID 29941461. S2CID 49411553.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Serotonin Receptor Agonists (Triptans)", LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury, Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2012, PMID 31644023, retrieved 2020-10-15

External links

- Tryptamine FAQ

- Tryptamine Hallucinogens and Consciousness

- Tryptamind Psychoactives, reference site on tryptamine and other psychoactives.

- Tryptamine (T) entry in TiHKAL • info