The Treaties of Erzurum were two treaties that were ratified in 1823 and 1847 which settled boundary disputes between the Ottoman Empire and Persia. [1]

First Treaty of 1823

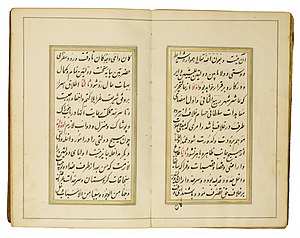

An official copy of the First Treaty of Erzurum.

Persian manuscript, created in

Qajar Iran, 19th century | |

| Type | Bilateral treaty |

|---|---|

| Signed | July 29, 1823 |

| Location | Erzurum, Ottoman Empire |

| Parties | |

Throughout history, there has been a constant primary concern of establishing an end to all hostility between the Ottoman Empire and Qajar Persia. Tensions between the two empires had been rising due to the Ottoman Empire's actions of harboring and withholding rebellious tribesmen from the Iranian Azerbaijan Province, which sparked issues with the Kurds. This tension led to an outbreak of wars between the two empires. The Persian also felt that their rights were being violated through unfair treatment by the Ottomans while the Ottomans struggled to view the Persian with respect and were not fond of their eastern neighbors until the Treaties of Erzurum were put in effect. With a goal of reaching a state of tranquility, it was attempted throughout multiple treaties that have all had the same objective in mind of achieving peace dating back to the Treaty of Zuhab in 1639 and leading all the way up to the final Treaty of Erzurum in 1848. Although the Treaty of Zuhab had established the boundary between the Ottoman Empire and Persia, the only clause that was stated in the treaty was that merchants from both realms could pass unharmed and unhampered into the lands of the other. [2] Although, the border in the mountainous Zuhab region remained a site of intermittent conflict in the subsequent two centuries. Over a century later, there were three issues that were still concerning Iranians the most: the levying of unfair taxes on pilgrims, the imposition of the jizya (the head tax on all adult male non-Muslims) on Iranian dhimmis, and the confiscation of the estates of deceased Iranian subjects. [2] Attempting to resolve these issues, the problem was addressed with the Treaty of Kerden in 1746, which affirmed the right of Iranian pilgrims to travel freely and limited the amount of custom duties they could be charged. This treaty, however, did not end the abuse of Iranian Muslims by Ottoman officials which is what led to continuous tension between the two states and what led to Karim Khan Zand invading Ottoman, Iraq in 1776 in attempt to punish the Ottomans for infractions of the treaty. [1] To add on top of that, the Russian Empire was secretly also attempting to put pressure on the Ottoman Empire, who was at war with the Greeks, whom were receiving arms from Russia. [3] At the instigation of the actions of the Russian Empire, Crown Prince Abbas Mirza of Persia, invaded Kurdistan and the areas surrounding Persian Azerbaijan, which led to the commencement of the Ottoman–Persian War. [3]

After the 1821 Battle of Erzurum, resulting in a Persian victory, both empires signed the first Treaty of Erzurum on July 1823, which confirmed the 1639 border. This treaty was composed of 21 leaves, 2 flyleaves, with 11 lines to the page. It was written in nasta'liq ink with the keywords highlighted in red catchwords, margins ruled in gold, and a camel-colored leather binding including an outer hard cover with a ribbon. The treaty had one main primary goal which was to re-establish the state of affairs that existed previously along the troublesome Kurdish frontier, where the Ottoman client state of Baban had just endured a civil war between pro-shah and pro-sultan factions, however the Iranians also wanted to achieve some purely economic objectives in their negotiations. [1] The treaty contained various economic and diplomatic clauses which stated that firstly, Iranian pilgrims would not be subjected to any extraordinary taxes that were ordinary to the Ottoman Empire and that their trade goods would be taxed at a fair and consistent rate. Secondly, the treaty regulated the taxes concerning the pilgrims and for the nomadic tribes pasturing their livestock in the borderlands. [4] There was a specific flat tax rate of 4% that was in direct proportion to the amount of goods that were being transported, which was collected at the first entry point of the merchant, likely Baghdad or Erzurum, or at Istanbul and the money would then be forwarded to Istanbul as part of the province's revenues. [1] There was also the regulation of the taxes concerning the pilgrims and for the nomadic tribes pasturing their livestock in the borderlands. [4] Thirdly, the treaty also allowed for Iranian merchants to freely trade in glass water pipes from Persia to Istanbul. Fourthly, Iranians wanted reforms to be instituted in the ways in which the estates of Iranians who died in the Ottoman Empire were handled. [1] Also included in the treaty, was the guaranteed access for Persian pilgrims to visit holy sites within the Ottoman Empire. [3] This had previously been promised by the 1746 Treaty of Kerden, but those rights had degraded over time. [1]

With the new Treaty in effect, there was a subtle progression in the way that the Ottomans viewed Persia. There was a shift from sectarian invectives from the 1746 Treaty of Kerden which were not in high favor of the Persian people that were not present in the Treaty of Erzurum. [1] Perhaps the clearest indication of change in the ways that the Ottomans perceived their eastern neighbors was the addition of Iran in 1823 to the list of countries which the bureaucrats at the Porte maintained separate registers of cases involving its citizens who needed state intervention. Although there was no guarantee of extraterritoriality in the treaty, the Ottoman bureaucrats started recognizing Iran as a separate nation whose subjects could call upon the central government for redress if their individual rights had been violated under the treaty - a privilege formerly only offered to European nations. [1] Iran was the first and only Muslim state to achieve this recognition from Istanbul. [1] There was also an agreement that every three years, Persia, as well as the Ottomans would send an envoy to the other country, therefore establishing permanent diplomatic relations with each other. [4]

Second Treaty of 1847

| Type | Bilateral treaty |

|---|---|

| Signed | May 31, 1847 |

| Location | Erzurum, Ottoman Empire |

| Effective | March 21, 1848 |

| Parties |

With the issue of Iranians still being taxed unjustly, and the Porte's fear of never seeing any of the revenue that was being collected on the rise, it instituted a very unwieldy regulation which stipulated that if a merchant would eventually be coming through Istanbul, then taxes would be collected in the capital. In such cases, the customs officers in the border cities were instructed to describe in a written report, but not to tax, all the merchandise being imported. That document would then be given to the merchant who would then present it upon arrival in Istanbul where he would pay the customs duties on the goods. [1] Having this system in place would help insure that both the merchants did not sell their goods along the way and that the central treasury would be able to collect their revenue. [1] However, due to all of the complaints that arose due to the mismanagement of this fiscal solution, it was discovered that Iranian merchants were not only actively trading in their usual destinations such as Baghdad, Aleppo, and Istanbul, but also in the Balkan cities which they were also apparently using as commercial gateways to Europe. [1] After 1830, however, it was discovered that the city from which most of the complaints had originated from was Trabzon. [1] This led to the certainty that trade between Iran and the Ottoman Empire was growing in the second quarter of the nineteenth century and that Iranian subjects, as opposed to Westerners, were its major purveyors. [1]

With the rising border incidents in the 1830s, the Ottoman Empire and Persia found themselves on the brink of war again. European powers Britain and Russia offered to not only mediate, but were also directly involved in its negotiation and drafting of the Treaty, and on May 31,1847, the second Treaty of Erzurum was signed. [5] [6] [7] This treaty consisted of nine articles which exemplified the transplantation of the European model of territorial sovereignty to the Middle East on the wings of European Imperialism. [6] [7] The treaty was the first serious attempt by the two leading powers of the Middle East to divide the disputed region between the two parties and provide for a boundary commission, composed of Ottoman, Persian, Russian, and British representatives, delimiting the entire border. [7] The boundary commission's work encountered several political setbacks but finally completed its task when the two countries agreed to the Constantinople Protocol of November 4, 1913. [8] [9] Once protocols were signed between Iran and the Ottoman state, the evolution of the Iranians into a community with extraterritorial rights received a major boost. In Article 6, it was stated that the tax rate set by the Treaty of Erzurum remained in effect and that no additional charge whatsoever shall be levied over and above the amounts fixed in said Treaty. [1] [6] Although this was not a change in innovation, there was a commercial treaty that was later signed with Great Britain, followed by one in France in which the import rate for Europeans was set at 12%. More significantly, the tax rate for Ottoman subjects was raised to 12% as well. [1] By contrast, the 4% rate for the subjects of the shah was reaffirmed in an order issued on January 4, 1859 which added that another 2% to the proportion of the estimated value of goods could be collected at the time of sale of the goods in the empire. [1] Perhaps the most notable change of all was that the same order stated that Iranians must now be treated the same as the Ottoman Muslims when reiterating their tax rate which was set at a lower rate for the Ottomans. [1]

Months after the new treaty, an order was received in Aleppo announcing that Khwaja Birz'a was named the shahbandar of Iran and that he was to be treated with the same consideration by city officials that was shown to other consuls of friendly nations. A few years later, officials in a number of other cities including Ankara, and Edirne had received the same orders. [1] Orders named that the Iranian officials in Ottoman cities stated that all cases involving Iranians, criminal or commercial, should be conducted according to the Sharia and that the shahbandar was to be present at the hearings and he could appeal ruling to Istanbul and as important as these changes were, they still did not confer extraterritoriality. [1] Although, the new rulings began giving distinct advantages in the Ottoman legal system to the Iranians and was represented the final shift in the evolution to full extraterritorial status. [1] In the final step to true extraterritoriality, the Iranians had to shift the Ottomans away from the Sharia to secular commercial laws. This final break with the past came with establishment of commercial courts in Istanbul in 1848 which seated both European and Ottoman judges and implemented a distinctly European commercial code. [1] When the Iranians were granted this right, they immediately pushed for the same legal exemptions that the Westerners were given and were finally granted these rights in a treaty that was signed between the two countries in 1875. [1] Fast forwarding to 1877, orders has been received in Aleppo in that stated the rights of Iranians to own property in the Ottoman realms. A similar order established the rights of citizens of the friendly countries including Italy, Austria, Sweden, Denmark, Spain, France, and Britain. [1] This transformation from the geopolitical concept was largely complete and Iran had become just another capitulatory power. This led to the Iranians becoming legally as foreign within the domains of the sultan as the Europeans. [1]

Legacy

The 1847 treaty was revoked by Iran after World War I and the establishment of the Mandatory Iraq. In the years just before World War I, Britain and Russia made new attempts to push a final settlement on the border, and more particularly on the Shatt al-Arab. On December 21, 1911, a protocol additional to the 1847 Treaty was signed between the two empires at Tehran. [7] The objective of this protocol was to revive Articles 1-3, and the parties accepted that any claims that could not be settled would refer to Article 4. [6] [7] After the compromise was laid down in the Protocol of Constantinople on November 17, 1913, the Ottoman Empire gave up the whole anchorage at Khorramshahr, which was essential for the exploitation of the oil concession that the British were holding from Iran, and which until after World War II, would be the most important in the whole Persian Gulf area. [7] The 1913 protocol also provided for the continuation of the activities of the commission. While the commission had made great progress by 1914, the eruption of war impeded the ratification and implementation of its achievements. [7] After the foundation of the Kingdom of Iraq at the end of the war, Iran proceeded to reject the additional protocols that were added onto the 1847 treaty. This led to continuous conflict between the two states, to the point where it was submitted to the Council of the League of Nations which only helped to clear some misunderstandings and barriers that led to the facilitation of a new treaty in 1937. This treaty was The Treaty of Tehran which was signed on July 4, 1937. [7] [10] [11] The Treaty of Tehran confirmed the previous treaties, but stipulated a new concession to Iran. Over a stretch of a few miles, between Khorramshahr and the great oil refinery at Abadan, the borderline between the two states was now fixed at the ' thalweg' which was the line formed by the lowest points in the valley and the river in the Shatt al-Arab, while for the rest of its course, the Shatt al-Arab remained fully under the sovereignty of Iraq. [7] After the Ba'ath rose to power in Iraq in 1968, the Iranian government rejected the 1937 treaty. Unresolved disputes over this part of the border would lead to the 1974–75 Shatt al-Arab conflict. [7] This conflict sparked the Iraq-Iran war and Iraq proceeded to attack Iran on September 22, 1980. Saddam Hussein sought to counter the revolutionary government of Ayatollah Khomeini, which had been attempting to destabilize Iraq's ruling Ba'ath government. [12] The ground invasion delivered Saddam the Shatt al-Arab waterway, thereby increasing Iraq's access to the Persian Gulf and redressing the humiliating concessions Saddam had been forced to make in the Algiers Accord of March 6, 1975. [12] The Iran-Iraq War lasted nearly eight years and ended on August 20, 1988 with the acceptance of the United Nations Security Council Resolution in 1987, first by Iraq and then by Iran. [7] [12] This resulted in Saddam Hussein reconfirming the border that had been settled by the 1975 compromise. [7] Today, Iran-Iraq relations have simmered down, with the two countries becoming trading partners. Iraq has an embassy in Tehran and three consulates in Kermanshah, Ahvaz, and Mashhad, while Iran has six diplomatic representative offices in Iraq including Baghdad, Basrah, Erbil, Karbala, Najaf, and Sulaymaniyah. [13] However, Kurdistan which is led by the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), is still not its own country and there are still some occasional disputes that occur with the Iranians, and the Turks as well.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Masters, Bruce (1991). "The Treaties of Erzurum (1823 and 1848) and the Changing Status of Iranians in the Ottoman Empire". Iranian Studies. 24 (1/4): 3–15. ISSN 0021-0862.

- ^ a b Masters, Bruce (1991). "The Treaties of Erzurum (1823 and 1848) and the Changing Status of Iranians in the Ottoman Empire". Iranian Studies. 24 (1/4): 3–15. ISSN 0021-0862.

- ^ a b c A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle, Vol.III, ed. Spencer C. Tucker, (ABC-CLIO, 2010), 1140.

- ^ a b c Ateş, Sabri (2013). Ottoman-Iranian Borderlands: Making a Boundary, 1843-1914. Cambridge University Press. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-1-107-03365-8.

- ^ Victor Prescott and Gillian D. Triggs, International Frontiers and Boundaries: Law, Politics and Geography (Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2008: ISBN 90-04-16785-4), p. 6.

- ^ a b c d "The Treaty of Erzurum". www.parstimes.com. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "The Iran-Iraq Border: A Story of Too Many Treaties". Oxford Public International Law. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- ^ Akhtar, Shameem (1969). "THE IRAQI-IRANIAN DISPUTE OVER THE SHATT-EL-ARAB". Pakistan Horizon. 22 (3): 213–220. ISSN 0030-980X.

- ^ "Protocol relating to the Delimitation of the Turco-Persian Boundary signed at Constantinople on November 4th (17th), 1913". www.parstimes.com. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- ^ Schofield, Julian; Zenko, Micah (2004). "Designing a Secure Iraq: A US Policy Prescription". Third World Quarterly. 25 (4): 677–687. ISSN 0143-6597.

- ^ Ghavami, Taghi (1974). "Shatt-Al-Arab (arvand-Rud) Crisis". Naval War College Review. 27 (2): 58–64. ISSN 0028-1484.

- ^ a b c "SADDAM HUSSEIN AND THE IRAN-IRAQ WAR" (PDF).

- ^ "Iran Embassy and Consulates in Iraq".

Bibliography

- Lambton, Ann K. S. "The Qajar Dynasty." In Qājār Persia: Eleven Studies, edited by Ann K. S. Lambton. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1987.