-

Terracotta image of Isis lamenting the loss of Osiris ( Eighteenth Dynasty, Egypt) Musée du Louvre, Paris

-

Etruscan " Sarcophagus of the Spouses", at the National Etruscan Museum, c 520 BCE

-

Indian terracotta figure, Gupta dynasty, at the National Museum, New Delhi

-

Han dynasty tomb brick relief

-

Bust of an unidentified man by Pierre Merard, 1786, France

-

British Museum, Seated Luohan from Yixian, from the Yixian glazed pottery luohans, probably of 1150–1250

-

Maximilien Robespierre, unglazed bust by Claude-André Deseine, 1791

-

Glazed building decoration at the Forbidden City, Beijing

-

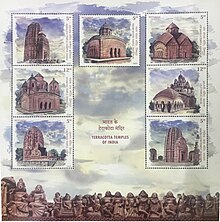

Terracotta temple, Bishnupur, India, a famous centre for terracotta temples

-

Hindu temple, 1739, Kalna, India

-

Terracotta designs outside the Kantajew Temple, Dinajpur, Bangladesh

-

The Bell Edison Telephone Building, Birmingham, England

-

The Natural History Museum in London has an ornate terracotta facade typical of high Victorian architecture. The carvings represent the contents of the Museum.

-

Bankura horses for sale in Bankura, West Bengal, India

-

Glazed terracotta casserole bowl

-

Salt-glazed terracotta jar

-

Terracotta vase. Crown Lynn, 1950s

Terracotta, also known as terra cotta or terra-cotta [2] (Italian: [ˌtɛrraˈkɔtta]; lit. 'baked earth'; [3] from Latin terra cocta 'cooked earth'), [4] is a term used in some contexts for earthenware. It is a clay-based non-vitreous ceramic, [5] fired at relatively low temperatures. [5]

Usage and definitions of the term vary, such as:

- In art, pottery, applied art, craft, construction and architecture, "terracotta" is a term often used for red-coloured earthenware sculptures or functional articles such as flower pots, water and waste water pipes, tableware, roofing tiles and surface embellishment on buildings. In such applications, the material is also called terracotta. [6]

- In archaeology and art history, "terracotta" is often used to describe objects such as figurines and loom weights not made on a potter's wheel, with vessels and other objects made on a wheel from the same material referred to as earthenware; the choice of term depends on the type of object rather than the material or shaping technique. [7]

- Terracotta is also used to refer to the natural brownish-orange color of most terracotta. [8]

Glazed architectural terracotta and its unglazed version as exterior surfaces for buildings were used in East Asia for centuries before becoming popular in the West in the 19th century. Architectural terracotta can also refer to decorated ceramic elements such as antefixes and revetments, which had a large impact on the appearance of temples and other buildings in the classical architecture of Europe, as well as in the Ancient Near East. [9]

This article covers the senses of terracotta as a medium in sculpture, as in the Terracotta Army and Greek terracotta figurines, and architectural decoration. East Asian and European sculpture in porcelain is not covered.

Production

Prior to firing, terracotta clays are easy to shape. Artifacts can be formed by an "additive" technique, adding portions of clay to the growing pieces, or a "subtractive" one, carving into a solid lump with a knife or similar tool. Sometime a combination of these is used: building up the broad shape and then removing or adding more in certain areas to produce details.

Other common shaping techniques include throwing and slip casting. [10] [11]

After drying, it is placed in a kiln or atop combustible material in a pit, and then fired. The typical firing temperature is around 1,000 °C (1,830 °F), though it may be as low as 600 °C (1,112 °F) in historic and archaeological examples. [12] During this process, the iron content of the clay reacts with oxygen, resulting in the iconic reddish color of terracotta clays. However, the overall color can vary widely, including shades of yellow, orange, buff, red, pink, grey or brown. [12]

A final method is to carve fired bricks or other terracotta shapes. This technique is less common, but examples can be found in the architecture of Bengal on Hindu temples and mosques.

Properties

Fired terracotta is not watertight, but its porousness decreases when the body is surface-burnished before firing. A layer of glaze can further decrease permeability and increase watertightness.

Unglazed terracotta is suitable for use below ground to carry pressurized water (an archaic use), for garden pots and irrigation or building decoration in many environments, and for oil containers, oil lamps, or ovens. Most other uses require the material to be glazed, such as tableware, sanitary piping, or building decorations built for freezing environments.

Terracotta will also ring if lightly struck, as long as it is not cracked. [13]

Painted (polychrome) terracotta is typically first covered with a thin coat of gesso, then painted. It is widely used, but only suitable for indoor positions and much less durable than fired colors in or under a ceramic glaze. Terracotta sculptures in the West were rarely left in their "raw" fired state until the 18th century. [14]

In art history

Terracotta female figurines were uncovered by archaeologists in excavations of Mohenjo-daro, Pakistan (3000–1500 BC). Along with phallus-shaped stones, these suggest some sort of fertility cult. [15] The Burney Relief is an outstanding terracotta plaque from Ancient Mesopotamia of about 1950 BC. In Mesoamerica, the great majority of Olmec figurines were in terracotta. Many ushabti mortuary statuettes were also made of terracotta in Ancient Egypt.

The Ancient Greeks' Tanagra figurines were mass-produced mold-cast and fired terracotta figurines, that seem to have been widely affordable in the Hellenistic period, and often purely decorative in function. They were part of a wide range of Greek terracotta figurines, which included larger and higher-quality works such as the Aphrodite Heyl; the Romans too made great numbers of small figurines, which were often used in a religious context as cult statues or temple decorations. [16] Etruscan art often used terracotta in preference to stone even for larger statues, such as the near life-size Apollo of Veii and the Sarcophagus of the Spouses. Campana reliefs are Ancient Roman terracotta reliefs, originally mostly used to make friezes for the outside of buildings, as a cheaper substitute for stone.

Indian sculpture made heavy use of terracotta from as early as the Indus Valley civilization (with stone and metal sculpture being rather rare), and in more sophisticated areas had largely abandoned modeling for using molds by the 1st century BC. This allows relatively large figures, nearly up to life-size, to be made, especially in the Gupta period and the centuries immediately following it. Several vigorous local popular traditions of terracotta folk sculpture remain active today, such as the Bankura horses. [17]

Precolonial West African sculpture also made extensive use of terracotta. [18] The regions most recognized for producing terracotta art in that part of the world include the Nok culture of central and north-central Nigeria, the Ife/ Benin cultural axis in western and southern Nigeria (also noted for its exceptionally naturalistic sculpture), and the Igbo culture area of eastern Nigeria, which excelled in terracotta pottery. These related, but separate, traditions also gave birth to elaborate schools of bronze and brass sculpture in the area. [19]

Chinese sculpture made great use of terracotta, with and without glazing and color, from a very early date. The famous Terracotta Army of Emperor Qin Shi Huang, 209–210 BC, was somewhat untypical, and two thousand years ago reliefs were more common, in tombs and elsewhere. Later Buddhist figures were often made in painted and glazed terracotta, with the Yixian glazed pottery luohans, probably of 1150–1250, now in various Western museums, among the most prominent examples. [20] Brick-built tombs from the Han dynasty were often finished on the interior wall with bricks decorated on one face; the techniques included molded reliefs. Later tombs contained many figures of protective spirits and animals and servants for the afterlife, including the famous horses of the Tang dynasty; as an arbitrary matter of terminology these tend not to be referred to as terracottas. [21]

European medieval art made little use of terracotta sculpture, until the late 14th century, when it became used in advanced International Gothic workshops in parts of Germany. [22] The Virgin illustrated at the start of the article from Bohemia is the unique example known from there. [1] A few decades later, there was a revival in the Italian Renaissance, inspired by excavated classical terracottas as well as the German examples, which gradually spread to the rest of Europe. In Florence Luca della Robbia (1399/1400–1482) was a sculptor who founded a family dynasty specializing in glazed and painted terracotta, especially large roundels which were used to decorate the exterior of churches and other buildings. These used the same techniques as contemporary maiolica and other tin-glazed pottery. Other sculptors included Pietro Torrigiano (1472–1528), who produced statues, and in England busts of the Tudor royal family. The unglazed busts of the Roman Emperors adorning Hampton Court Palace, by Giovanni da Maiano, 1521, were another example of Italian work in England. [23] They were originally painted but this has now been lost from weathering.

In the 18th-century unglazed terracotta, which had long been used for preliminary clay models or maquettes that were then fired, became fashionable as a material for small sculptures including portrait busts. It was much easier to work than carved materials, and allowed a more spontaneous approach by the artist. [24] Claude Michel (1738–1814), known as Clodion, was an influential pioneer in France. [25] John Michael Rysbrack (1694–1770), a Flemish portrait sculptor working in England, sold his terracotta modelli for larger works in stone, and produced busts only in terracotta. [26] In the next century the French sculptor Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse made many terracotta pieces, [27] but possibly the most famous is The Abduction of Hippodameia depicting the Greek mythological scene of a centaur kidnapping Hippodameia on her wedding day.

Architecture

Terracotta tiles have a long history in many parts of the world. Many ancient and traditional roofing styles included more elaborate sculptural elements than the plain roof tiles, such as Chinese Imperial roof decoration and the antefix of western classical architecture. In India West Bengal made a speciality of terracotta temples, with the sculpted decoration from the same material as the main brick construction.

In the 19th century the possibilities of terracotta decoration of buildings were again appreciated by architects, often using thicker pieces of terracotta, and surfaces that are not flat. [28] The American architect Louis Sullivan is well known for his elaborate glazed terracotta ornamentation, designs that would have been impossible to execute in any other medium. Terracotta and tile were used extensively in the town buildings of Victorian Birmingham, England. Terra cotta was marketed as a miracle material, largely impervious to the elements. Terra cotta, however, can indeed be damaged by water penetration or exposure or fail through faulty design or installation. An excessive faith in the durability of the material led to shortcuts in design and execution, which coupled with a belief that the material did not require maintenance tainted the reputation of the material. By about 1930 the widespread use of concrete and Modernist architecture largely ended the use of terracotta in architecture. [29] It has been defined as 'Unglazed fired clay building blocks and moulded ornamental building components.' [30]

Terracotta tiles have also been used extensively for floors since ancient times. The quality of terracotta floor tiles depends on the suitability of the clay, the manufacturing methods (kiln-fired being more durable than sun baked), and whether the terracotta tiles are sealed or not.

Advantages in sculpture

As compared to bronze sculpture, terracotta uses a far simpler and quicker process for creating the finished work with much lower material costs. The easier task of modelling, typically with a limited range of knives and wooden shaping tools, but mainly using the fingers, [31] allows the artist to take a more free and flexible approach. Small details that might be impractical to carve in stone, of hair or costume for example, can easily be accomplished in terracotta, and drapery can sometimes be made up of thin sheets of clay that make it much easier to achieve a realistic effect. [32]

Reusable mold-making techniques may be used for production of many identical pieces. Compared to marble sculpture and other stonework the finished product is far lighter and may be further painted and glazed to produce objects with color or durable simulations of metal patina. Robust durable works for outdoor use require greater thickness and so will be heavier, with more care needed in the drying of the unfinished piece to prevent cracking as the material shrinks. Structural considerations are similar to those required for stone sculpture; there is a limit on the stress that can be imposed on terracotta, and terracotta statues of unsupported standing figures are limited to well under life-size unless extra structural support is added. This is also because large figures are extremely difficult to fire, and surviving examples often show sagging or cracks. [33] The Yixian figures were fired in several pieces, and have iron rods inside to hold the structure together. [34]

India

History

Terracotta has been the medium for art since the Harappan civilization. But the techniques used differed in each time period. In the Mauryan times, they were mainly figures of mother goddesses, indicating a fertility cult. Moulds were used for the face, whereas the body was hand-modelled. In the Shungan times, a single mould was used to make the entire figure and depending upon the baking time, the colour differed from red to light orange. The Satavahanas used two different moulds- one for the front and the other for the back and kept a piece of clay in each mould and joined them together, making some artefacts hollow from within. Some Satavahana terracotta artefacts also seem to have a thin strip of clay joining the two moulds. This technique may have been imported from the Romans and is seen nowhere else in the country. [35]

Present

The practice of terracotta art and its production continues even today in several states of India. The major centres that continue the practice in modern times include West Bengal, Bihar, Jharkhand, Rajasthan, and Tamil Nadu. In Bishnupur, West Bengal, the terracotta pattern–panels on the temples are known for their intricate details. The Bankura Horse is also very famous and belongs to the Bengal school of terracotta. Madhya Pradesh is one of the most prominent production centres of terracotta art today. The tribes of the Bastar area carry forward the rich tradition. They make intricate designs and statues of animals and birds. Hand-painted clay and terracotta products are famous in Gujarat. The Aiyanar cult in Tamil Nadu is associated with life-size terracotta statues. [36]

Traditional terracotta sculptures, mainly religious, also continue to be made. The demand for this craft is seasonal, reaching its peak during the harvest festival, when new pottery and votive idols are required. During the rest of the year, crafters rely on agriculture or some other means of income. The designs are often redundant as crafters apply similar reliefs and techniques for different subjects. The client suggest subjects and uses for each piece. This craft requires a strong understanding of composition and subject matter as well as skill to effectively to give each plaque its distinct character with patience. [37]

To sustain the legacy, the Indian Government has established the Sanskriti Museum of Indian Terracotta in New Delhi. The initiative encourages ongoing work in this medium through displays terracotta from different sub-continent regions and periods. From the Indus civilization to modern times, the Indian Terracotta school has incorporated various styles, techniques, methods, doctrines, and grammar. It borrows from diverse schools and traditions that range from realism to abstract. In 2010, the India Post Service issued a stamp commemorating the rich craft and its part in India's artistic tradition since the hoary past. The stamp shows a terracotta doll from the craft museum.

Gallery

See also

- Architectural terracotta

- Cittacotte

- John Marriott Blashfield, terracotta manufacturer

- Kulhar – traditional terracotta cups

- Majapahit Terracotta

- Redware

- Structural clay tile

- Tile Heritage Foundation

- Saltillo Terracotta Tile

- Bishnupur, Bankura

- Panchmura

- Bankura horse

Notes

- ^ a b Bust of the Virgin, ca. 1390–95, In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. (October 2008)

- ^ "Terracotta" is normal in British English, and perhaps globally more common in art history. "Terra-cotta" is more popular in general American English.

- ^ "terra-cotta". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary.

- ^ "Terracotta", p. 341, Delahunty, Andrew, From Bonbon to Cha-cha: Oxford Dictionary of Foreign Words and Phrases, 2008, OUP Oxford, ISBN 0199543690, 9780199543694; book

- ^ a b OED, "Terracotta"; "Terracotta", MFA Boston, "Cameo" database

- ^ 'Industrial Ceramics.' F.Singer, S.S.Singer. Chapman & Hall. 1971. Quote: "The lighter pieces that are glazed may also be termed 'terracotta.'

- ^ Peek, Philip M., and Yankah, African Folklore: An Encyclopedia, 2004, Routledge, ISBN 1135948720, 9781135948726, google books

- ^ "Home : Oxford English Dictionary". www.oed.com. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ "The many uses of terracotta tiles - a designers history". Lubelska. 2019-05-21. Retrieved 2020-10-07.

- ^ 'Technical Trends Of Cottage Ceramic Industries In Southwestern Nigeria' Journal of Visual Art and Design. Segun Oladapo Abiodun. Vol. 10, No. 1, 2018

- ^ 'Mechanisms To Improve Energy Efficiency In Small Industries. Part Two: Pottery In India And Khurja' A. Rath, DFID Project R7413. Policy Research International

- ^ a b Grove, 1

- ^ Dasgupta, Chittaranjan (2015). Collection of Essays on Terracotta Temples of Bishnupur (in Bengali). ISBN 9789385663109.

- ^ Grove, 2, i, a

- ^ Neusner, Jacob, ed. (2003). World Religions in America. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press.

- ^ Richardson, Emeline Hill (1953). "The Etruscan Origins of Early Roman Sculpture". Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome. 21: 75–124. doi: 10.2307/4238630. ISSN 0065-6801. JSTOR 4238630.

- ^ Grove, 5

- ^ H. Meyerowitz; V. Meyerowitz (1939). "Bronzes and Terra-Cottas from Ile-Ife". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 75 (439), 150–152; 154–155.

- ^ Grove, 3

- ^ Rawson, 140-145; Grove, 4

- ^ Rawson, 140-145,159-161

- ^ Schultz, 67-68

- ^ Grove, "Florence"

- ^ Draper and Scherf, 2-7 and throughout; Grove, 2, i, a and c

- ^ Well covered in Draper and Scherf, see index; Grove, 2, i, a and c

- ^ Grove, 2, i, c

- ^ Grove, 2, i, d

- ^ Grove, 2, ii

- ^ Grove, 2, ii, c and d

- ^ Dictionary of Ceramics 3rd edition. Dodd A., Murfin D., The Institute of Materials. 1994.

- ^ Grove, 2, i, a; Scultz, 167

- ^ Scultz, 67, 167

- ^ Scultz; Hobson, R.L. (May 1914). "A New Chinese Masterpiece in the British Museum". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. Vol. 25, no. 134. p. 70. JSTOR 859579.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Lecture by Derek Gillman at the Penn Museum, on their example and the group of Yixian figures. From YouTube". YouTube.

- ^ "National Museum, New Delhi". www.nationalmuseumindia.gov.in. Retrieved 2023-05-04.

- ^ Shyam Singh Rawat. A Historical Journey Of Indian Terracotta From Indus Civilization Up To Contemporary Art. European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine. Volume 07, Issue 07, 2020. https://ejmcm.com/article_5016_6156ca1810f72ca7bae4a7de754c9a0e.pdf

- ^ "Gaatha.org ~ Craft ~ Molela terracota". gaatha.org.

References

- Draper, James David and Scherf, Guilhem (eds.), Playing with Fire: European Terracotta Models, 1740-1840, 2003, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 1588390993, 9781588390998, fully available on Google books

- C. A. Galvin; et al. (2003). "Terracotta [It.: 'cooked earth']". Terracotta. Grove Art Online. Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T083896. ISBN 9781884446054.

- Rainer Kahnitz (1986). "Sculpture in Stone, Terracotta, and Wood". In Schultz, Ellen (ed.). Gothic and Renaissance Art in Nuremberg. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 67. ISBN 9780870994661.

External links

- Article on terracotta in Victorian and Edwardian Terracotta Buildings

- Bibliography, Smithsonian Institution, Ceramic Tiles and Architectural Terracotta

- Friends of Terra Cotta, non-profit foundation to promote education and preservation of architectural Terracotta

- Tiles and Architectural Ceramics Society (UK)

- Guidance on Matching Terracotta Practical guidance on the repair and replacement of historic terracotta focusing on the difficulties associated with trying to match new to old

- Throwing a terracotta pot on a wheel

- Slipcasting terracotta