This article has multiple issues. Please help

improve it or discuss these issues on the

talk page. (

Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Romance | |

|---|---|

| Latin/Neo-Latin | |

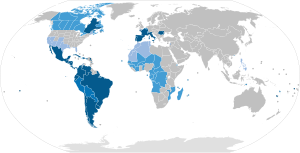

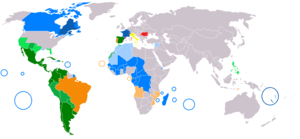

| Geographic distribution | Originated in Old Latium on the Apennine Peninsula, now also spoken in Latin Europe (parts of Eastern Europe, Southern Europe, and Western Europe) and Latin America (a majority of the countries of Central America and South America), as well as parts of Africa ( Latin Africa), Asia, and Oceania. |

| Linguistic classification |

Indo-European

|

Early forms | |

| Proto-language | Proto-Romance |

| Subdivisions | |

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | roa |

| Linguasphere | 51- (phylozone) |

| Glottolog | roma1334 |

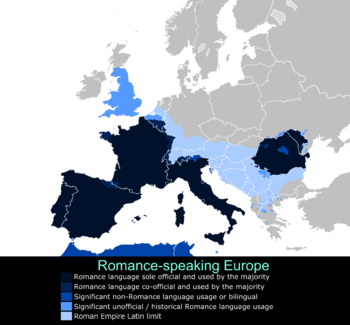

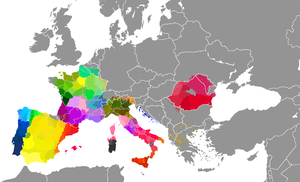

Romance languages in Europe | |

Romance languages across the world Majority native language

Co-official and majority native language

Official but minority native language

Cultural or secondary language | |

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

The Romance languages, also known as the Latin [1] or Neo-Latin [2] languages, are the languages that are directly descended from Vulgar Latin. [3] They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic branch of the Indo-European language family.

The five most widely spoken Romance languages by number of native speakers are Spanish (489 million), Portuguese (240 million), [4] French (80 million), Italian (67 million) and Romanian (24 million), which are all national languages of their respective countries of origin. There are more than 900 million native speakers of Romance languages found worldwide, mainly in the Americas, Europe, and parts of Africa. Portuguese, French and Spanish also have many non-native speakers and are in widespread use as linguae francae. [5] There are also numerous regional Romance languages and dialects.

Name and languages

The term Romance derives from the Vulgar Latin adverb romanice, "in Roman", derived from romanicus: for instance, in the expression romanice loqui, "to speak in Roman" (that is, the Latin vernacular), contrasted with latine loqui, "to speak in Latin" ( Medieval Latin, the conservative version of the language used in writing and formal contexts or as a lingua franca), and with barbarice loqui, "to speak in Barbarian" (the non-Latin languages of the peoples living outside the Roman Empire). [6] From this adverb the noun romance originated, which applied initially to anything written romanice, or "in the Roman vernacular". [7]

Most of the Romance-speaking area in Europe has traditionally been a dialect continuum, where the speech variety of a location differs only slightly from that of a neighboring location, but over a longer distance these differences can accumulate to the point where two remote locations speak what may be unambiguously characterized as separate languages. This makes drawing language boundaries difficult, and as such there is no unambiguous way to divide the Romance varieties into individual languages. Even the criterion of mutual intelligibility can become ambiguous when it comes to determining whether two language varieties belong to the same language or not. [8]

The following is a list of groupings of Romance languages, with some languages and dialects chosen to exemplify each grouping. These groupings should not be interpreted as well-separated genetic clades in a tree model:

- Ibero-Romance: Portuguese, Galician, Asturleonese/ Mirandese, Spanish, Aragonese, Ladino;

- Occitano-Romance: Catalan/ Valencian, Occitan (lenga d'oc), Gascon (sometimes not considered part of Occitan);

- Gallo-Romance: French/ Oïl languages, Franco-Provençal (Arpitan);

- Rhaeto-Romance: Romansh, Ladin, Friulian;

- Gallo-Italic: Piedmontese, Ligurian, Lombard, Emilian, Romagnol;

- Venetan (classification disputed);

- Italo-Dalmatian: Italian ( Tuscan, Corsican, Sassarese, Central Italian), Sicilian/ Extreme Southern Italian, Neapolitan/ Southern Italian, Dalmatian (extinct in 1898), Istriot;

- Eastern Romance: Romanian, Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian, Istro-Romanian;

- Sardinian: Campidanese, Logudorese

Modern status

This section needs additional citations for

verification. (March 2022) |

The Romance language most widely spoken natively today is Spanish, followed by Portuguese, French, Italian and Romanian, which together cover a vast territory in Europe and beyond, and work as official and national languages in dozens of countries. [9]

In Europe, at least one Romance language is official in France, Portugal, Spain, Italy, Switzerland, Belgium, Romania, Moldova, Transnistria, Monaco, Andorra, San Marino and Vatican City. In these countries, French, Portuguese, Italian, Spanish, Romanian, Moldovan, Romansh and Catalan have constitutional official status.

French, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, and Romanian are also official languages of the European Union. [10] Spanish, Portuguese, French, Italian, Romanian, and Catalan were the official languages of the defunct Latin Union; [11] and French and Spanish are two of the six official languages of the United Nations. [12] Outside Europe, French, Portuguese and Spanish are spoken and enjoy official status in various countries that emerged from the respective colonial empires. [13] [14] [15]

Spanish is an official language in Spain and in nine countries of South America, home to about half that continent's population; in six countries of Central America (all except Belize); and in Mexico. In the Caribbean, it is official in Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Puerto Rico. In all these countries, Latin American Spanish is the vernacular language of the majority of the population, giving Spanish the most native speakers of any Romance language. In Africa it is one of the official languages of Equatorial Guinea. Spanish was one of the official languages in the Philippines in Southeast Asia until 1973. During the 1987 constitution, Spanish was de-listed as an official language (replaced with English), and was listed as an optional/voluntary language along with Arabic. It is currently spoken by a minority and taught in the school curriculum.

Portuguese, in its original homeland, Portugal, is spoken by virtually the entire population of 10 million. As the official language of Brazil, it is spoken by more than 200 million people in that country, as well as by neighboring residents of eastern Paraguay and northern Uruguay, accounting for a little more than half the population of South America, thus making Portuguese the most spoken official Romance language in a single country. It is the official language of six African countries ( Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, Equatorial Guinea, and São Tomé and Príncipe), and is spoken as a native language by perhaps 16 million residents of that continent. [16] [ better source needed] In Asia, Portuguese is co-official with other languages in East Timor and Macau, while most Portuguese-speakers in Asia—some 400,000 [17]—are in Japan due to return immigration of Japanese Brazilians. In North America 1,000,000 people speak Portuguese as their home language, mainly immigrants from Brazil, Portugal, and other Portuguese-speaking countries and their descendants. [18] In Oceania, Portuguese is the second most spoken Romance language, after French, due mainly to the number of speakers in East Timor. Its closest relative, Galician, has official status in the autonomous community of Galicia in Spain, together with Spanish.[ citation needed]

Outside Europe, French is spoken natively most in the Canadian province of Quebec, and in parts of New Brunswick and Ontario. Canada is officially bilingual, with French and English being the official languages and government services in French theoretically mandated to be provided nationwide. In parts of the Caribbean, such as Haiti, French has official status, but most people speak creoles such as Haitian Creole as their native language. French also has official status in much of Africa, with relatively few native speakers but larger numbers of second language speakers. French is spoken by around 300 to 450 million people in 2022 according to Ethnologue and the OIF. [19] [20] In Europe, French is spoken by 71 million native speakers and nearly 200 million Europeans can speak French, making French the second most spoken language in Europe after English. [21] French is also the second most studied language in the world behind English, with about 130 million learners in 2017. [22]

Although Italy also had some colonial possessions before World War II, its language did not remain official after the end of the colonial domination. As a result, Italian outside of Italy and Switzerland is now spoken only as a minority language by immigrant communities in North and South America and Australia. In some former Italian colonies in Africa—namely Libya, Eritrea and Somalia—it is spoken by a few educated people in commerce and government.[ citation needed]

Romania did not establish a colonial empire. The native range of Romanian includes not only the Republic of Moldova, where it is the dominant language and spoken by a majority of the population, but neighboring areas in Serbia ( Vojvodina and the Bor District), Bulgaria, Hungary, and Ukraine ( Bukovina, Budjak) and in some villages between the Dniester and Bug rivers. [23] As with Italian, Romanian is spoken outside of its ethnic range by immigrant communities. In Europe, Romanian-speakers form about two percent of the population in Italy, Spain, and Portugal. Romanian is also spoken in Israel by Romanian Jews, [24] where it is the native language of five percent of the population, [25] and is spoken by many more as a secondary language. The Aromanian language is spoken today by Aromanians in Bulgaria, North Macedonia, Albania, Kosovo, and Greece. [26]

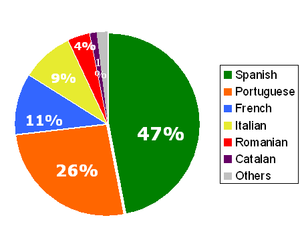

The total of 880 million native speakers of Romance languages (ca. 2020) are divided as follows: [19]

- Spanish 55% (500 million, plus 100 million L2 for 600 million Hispanophones)

- Portuguese 26% (230 million, plus 30 million L2 for 260 million Lusophones)

- French 9% (100 million, plus 350 million L2 for 450 million Francophones)

- Italian 6% (65 million, plus 3 million L2)

- Romanian 3% (24 million)

- Catalan 0.5% (4 million, plus 5 million L2)

- Others 3% (26 million, nearly all bilingual in one of the national languages)

Catalan is the official language of Andorra. In Spain, it is co-official with Spanish in Catalonia, the Valencian Community (under the name Valencian), and the Balearic Islands, and it is recognized, but not official, in an area of Aragon known as La Franja. In addition, it is spoken by many residents of Alghero, on the island of Sardinia, and it is co-official in that city. [27] Galician, with more than a million native speakers, is official together with Spanish in Galicia, and has legal recognition in neighbouring territories in Castilla y León. A few other languages have official recognition on a regional or otherwise limited level; for instance, Asturian and Aragonese in Spain; Mirandese in Portugal; Friulian, Sardinian and Franco-Provençal in Italy; and Romansh in Switzerland.[ This paragraph needs citation(s)]

The remaining Romance languages survive mostly as spoken languages for informal contact. National governments have historically viewed linguistic diversity as an economic, administrative or military liability, as well as a potential source of separatist movements; therefore, they have generally fought to eliminate it, by extensively promoting the use of the official language, restricting the use of the other languages in the media, recognizing them as mere "dialects", or even persecuting them. As a result, all of these languages are considered endangered to varying degrees according to the UNESCO Red Book of Endangered Languages, ranging from "vulnerable" (e.g. Sicilian and Venetian) to "severely endangered" ( Franco-Provençal, most of the Occitan varieties). Since the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, increased sensitivity to the rights of minorities has allowed some of these languages to start recovering their prestige and lost rights. Yet it is unclear whether these political changes will be enough to reverse the decline of minority Romance languages.[ This paragraph needs citation(s)]

History

Between 350 BC and 150 AD, the expansion of the Empire, together with its administrative and educational policies, made Latin the dominant native language in continental Western Europe. Latin also exerted a strong influence in southeastern Britain, the Roman province of Africa, western Germany, Pannonia and the whole Balkans. [28]

During the Empire's decline, and after its fragmentation and the collapse of its Western half in the fifth and sixth centuries, the spoken varieties of Latin became more isolated from each other, with the western dialects coming under heavy Germanic influence (the Goths and Franks in particular) and the eastern dialects coming under Slavic influence. [29] [30] The dialects diverged from Latin at an accelerated rate and eventually evolved into a continuum of recognizably different typologies. The colonial empires established by Portugal, Spain, and France from the fifteenth century onward spread their languages to the other continents to such an extent that about two-thirds of all Romance language speakers today live outside Europe.

Despite other influences (e.g. substratum from pre-Roman languages, especially Continental Celtic languages; and superstratum from later Germanic or Slavic invasions), the phonology, morphology, and lexicon of all Romance languages consist mainly of evolved forms of Vulgar Latin. However, some notable differences occur between today's Romance languages and their Roman ancestor. With only one or two exceptions, Romance languages have lost the declension system of Latin and, as a result, have SVO sentence structure and make extensive use of prepositions. [31] By some measures, Sardinian and Italian are the least divergent languages from Latin, while French has changed the most. [32] However, all Romance languages are closer to each other than to classical Latin. [33] [34]

Vulgar Latin

Documentary evidence about Vulgar Latin for the purposes of comprehensive research is limited, and the literature is often hard to interpret or generalize. Many of its speakers were soldiers, slaves, displaced peoples, and forced resettlers, and more likely to be natives of conquered lands than natives of Rome. In Western Europe, Latin gradually replaced Celtic and other Italic languages, which were related to it by a shared Indo-European origin. Commonalities in syntax and vocabulary facilitated the adoption of Latin. [36] [37] [38]

To some scholars, this suggests the form of Vulgar Latin that evolved into the Romance languages was around during the time of the Roman Empire (from the end of the first century BC), and was spoken alongside the written Classical Latin which was reserved for official and formal occasions. Other scholars argue that the distinctions are more rightly viewed as indicative of sociolinguistic and register differences normally found within any language. With the rise of the Roman Empire, spoken Latin spread first throughout Italy and then through southern, western, central, and southeastern Europe, and northern Africa along parts of western Asia. [39]: 1

Latin reached a stage when innovations became generalised around the sixth and seventh centuries. [40] After that time and within two hundred years, it became a dead language since "the Romanized people of Europe could no longer understand texts that were read aloud or recited to them." [41] By the eighth and ninth centuries Latin gave way to Romance. [42]

Fall of the Western Roman Empire

During the political decline of the Western Roman Empire in the fifth century, there were large-scale migrations into the empire, and the Latin-speaking world was fragmented into several independent states. Central Europe and the Balkans were occupied by Germanic and Slavic tribes, as well as by Huns.

British and African Romance—the forms of Vulgar Latin used in Britain and the Roman province of Africa, where it had been spoken by much of the urban population—disappeared in the Middle Ages (as did Moselle Romance in Germany). But the Germanic tribes that had penetrated Roman Italy, Gaul, and Hispania eventually adopted Latin/Romance and the remnants of the culture of ancient Rome alongside existing inhabitants of those regions, and so Latin remained the dominant language there. In part due to regional dialects of the Latin language and local environments, several languages evolved from it. [39]: 4

Fall of the Eastern Roman empire

Meanwhile, large-scale migrations into the Eastern Roman Empire started with the Goths and continued with Huns, Avars, Bulgars, Slavs, Pechenegs, Hungarians and Cumans. The invasions of Slavs were the most thoroughgoing, and they partially reduced the Romanic element in the Balkans. [43] The invasion of the Turks and conquest of Constantinople in 1453 marked the end of the empire.

The surviving local Romance languages were Dalmatian and Common Romanian. Out of the latter the Eastern Romance languages developed, resulting in four dialects: Daco-Romanian dialect became fully distinct from the southern dialect of Aromanian before the eleventh century, and from Istro-Romanian not before the thirteenth, while the position of Megleno-Romanian is unclear. Romanian emerged as a literary language in the sixteenth century. [44]

Early Romance

Over the course of the fourth to eighth centuries, local changes in phonology, morphology, syntax and lexicon accumulated to the point that the speech of any locale was noticeably different from another. In principle, differences between any two lects increased the more they were separated geographically, reducing easy mutual intelligibility between speakers of distant communities. [45] Clear evidence of some levels of change is found in the Reichenau Glosses, an eighth-century compilation of about 1,200 words from the fourth-century Vulgate of Jerome that had changed in phonological form or were no longer normally used, along with their eighth-century equivalents in proto- Franco-Provençal. [46] The following are some examples with reflexes in several modern Romance languages for comparison:[ citation needed]

| English | Classical / 4th cent. (Vulgate) |

8th cent. (Reichenau) |

Franco-Provençal | French | Romansh | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Romanian | Catalan | Sardinian | Occitan | Ladin | Neapolitan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| once | semel | una vice | una vês / una fês | une fois | (ina giada) | (una volta) | una vez | uma vez | (o dată) | una vegada (un cop, una volta) |

(una borta) | una fes (un còp) |

n iede | na vota |

| children/infants | liberi / infantes | infantes | enfants | enfants | unfants | (bambini) / infanti |

(niños) / infantes |

infantes (crianças) | (copii) / infanți | (nens, etc.) / infants |

(pipius) / (pitzinnos) | enfants | mutons | criature |

| to blow | flare / sofflare | suflare | sofllar | souffler | suflar | soffiare | soplar | soprar | (a) sufla | (bufar) | sulai / sulare | bufar | suflé | sciuscià |

| to sing | canere | cantare | chantar | chanter | chantar | cantare | cantar | cantar | (a) cânta | cantar | cantai / cantare | cantar | cianté | cantà |

| the best (plur.) | optimi / meliores | meliores | los mèlyors | les meilleurs | ils megliers | i migliori | los mejores | os melhores | (optimi, cei mai buni) |

els millors | is mellus / sos menzus | Los/lei melhors | i miëures | 'e meglie |

| beautiful | pulchra / bella | bella | bèla | belle | bella | bella | (hermosa, bonita, linda) / bella |

bela / (formosa, bonita, linda) |

frumoasă | (bonica, polida) / bella |

bella | bèla | bela | bella |

| in the mouth | in ore | in bucca | en la boche | dans la bouche | in la bucca | nella bocca | en la boca | na boca [47] | (în gură) / în bucă [48] (a îmbuca) [49] | a la boca | in sa buca | dins la boca | te la bocia | 'n bocca (/ˈmmokkə/) |

| winter | hiems | hibernus | hivèrn | hiver | inviern | inverno | invierno | inverno | iarnă | hivern | ierru / iberru | ivèrn | inviern | vierno |

In all of the above examples, the words appearing in the fourth century Vulgate are the same words as would have been used in Classical Latin of c. 50 BC. It is likely that some of these words had already disappeared from casual speech by the time of the Glosses; but if so, they may well have been still widely understood, as there is no recorded evidence that the common people of the time had difficulty understanding the language. By the 8th century, the situation was very different. During the late 8th century, Charlemagne, holding that "Latin of his age was by classical standards intolerably corrupt", [45]: 6 successfully imposed Classical Latin as an artificial written vernacular for Western Europe. Unfortunately, this meant that parishioners could no longer understand the sermons of their priests, forcing the Council of Tours in 813 to issue an edict that priests needed to translate their speeches into the rustica romana lingua, an explicit acknowledgement of the reality of the Romance languages as separate languages from Latin. [45]: 6

By this time, and possibly as early as the 6th century according to Price (1984), [45]: 6 the Romance lects had split apart enough to be able to speak of separate Gallo-Romance, Ibero-Romance, Italo-Romance and Eastern Romance languages. Some researchers[ who?] have postulated that the major divergences in the spoken dialects began or accelerated considerably in the 5th century, as the formerly widespread and efficient communication networks of the Western Roman Empire rapidly broke down, leading to the total disappearance of the Western Roman Empire by the end of the century. During the period between the 5th–10th centuries AD Romance vernaculars documentation is scarce as the normal writing language used was Medieval Latin, with vernacular writing only beginning in earnest in the 11th or 12th century. The earliest such texts are the Indovinello Veronese from the eight century and the Oaths of Strasbourg from the second half of the ninth century. [50]

Recognition of the vernaculars

• Early Middle Ages

• Early Twentieth Century

From the 10th [52] century onwards, some local vernaculars developed a written form and began to supplant Latin in many of its roles. In some countries, such as Portugal, this transition was expedited by force of law; whereas in others, such as Italy, many prominent poets and writers used the vernacular of their own accord – some of the most famous in Italy being Giacomo da Lentini and Dante Alighieri. Well before that, the vernacular was also used for practical purposes, such as the testimonies in the Placiti Cassinesi, written 960–963. [53]

Uniformization and standardization

The invention of the printing press brought a tendency towards greater uniformity of standard languages within political boundaries, at the expense of other Romance languages and dialects less favored politically. In France, for instance, the dialect spoken in the region of Paris gradually spread to the entire country, and the Occitan of the south lost ground.

Samples

Lexical and grammatical similarities among the Romance languages, and between Latin and each of them, are apparent from the following examples in various Romance lects, all meaning 'She always closes the window before she dines/before dining'.

Latin (Ea) semper antequam cenat fenestram claudit. Apulian (Ièdde) achiùde sèmbe la fenèstre prime de mangè. Aragonese (Ella) zarra siempre a finestra antes de cenar. Aromanian (Ea/Nâsa) ãncljidi/nkidi totna firida/fireastra ninti di tsinã. Asturian (Ella) pieslla siempres la ventana enantes de cenar. Cantabrian (Ella) tranca siempri la ventana enantis de cenar. Catalan (Ella) sempre/tostemps tanca la finestra abans de sopar. Northern Corsican Ella chjode/chjude sempre lu/u purtellu avanti/nanzu di cenà. Southern Corsican Edda/Idda sarra/serra sempri u purteddu nanzu/prima di cinà. Dalmatian Jala insiara sianpro el balkáun anínč de kenúr. Eastern Lombard (Le) la sàra sèmper la fenèstra prìma de diznà. Emilian ( Reggiano) (Lē) la sèra sèmpar sù la fnèstra prima ad snàr. Emilian ( Bolognese) (Lî) la sèra sänper la fnèstra prémma ed dṡnèr. Emilian ( Placentine) Ad sira lé la sèra seimpar la finéstra prima da seina. Extremaduran (Ella) afecha siempri la ventana antis de cenal. Franco-Provençal (Le) sarre toltin/tojor la fenétra avan de goutâ/dinar/sopar. French Elle ferme toujours la fenêtre avant de dîner/souper. Friulian (Jê) e siere simpri il barcon prin di cenâ. Galician (Ela) pecha/fecha sempre a fiestra/xanela antes de cear. Gallurese Idda chjude sempri lu balconi primma di cinà. Italian (Ella/lei) chiude sempre la finestra prima di cenare. Judaeo-Spanish אֵילייה סֵירּה שֵׂימפּרֵי לה װֵינטאנה אנטֵיז דֵי סֵינאר.

Ella cerra sempre la ventana antes de cenar.Ladin Badiot: Ëra stlüj dagnora la finestra impröma de cenè.

Centro Cadore: La sera sempre la fenestra gnante de disna.

Auronzo di Cadore: La sera sempro la fenestra davoi de disnà.

Gherdëina: Ëila stluj for l viere dan maië da cëina.Leonese (Eilla) pecha siempre la ventana primeiru de cenare. Ligurian (Le) a saera sempre u barcun primma de cenà. Lombard (east.)

(Bergamasque)(Lé) la sèra sèmper sö la finèstra prima de senà. Lombard (west.) (Lee) la sara sù semper la finestra primma de disnà/scenà. Magoua (Elle) à fàrm toujour là fnèt àvan k'à manj. Mirandese (Eilha) cerra siempre la bentana/jinela atrás de jantar. Neapolitan Essa 'nzerra sempe 'a fenesta primma d'a cena / 'e magnà. Norman Lli barre tréjous la crouésie devaunt de daîner. Occitan (Ela) barra/tanca sempre/totjorn la fenèstra abans de sopar. Picard Ale frunme tojours l' croésèe édvint éd souper. Piedmontese Chila a sara sèmper la fnestra dnans ëd fé sin-a/dnans ëd siné. Portuguese (Ela) fecha sempre a janela antes de jantar. Romagnol (Lia) la ciud sëmpra la fnèstra prëma ad magnè. Romanian (Ea) închide întotdeauna fereastra înainte de a cina. Romansh Ella clauda/serra adina la fanestra avant ch'ella tschainia. South Sardinian (Campidanese) Issa serrat semp(i)ri sa bentana in antis de cenai North Sardinian (Logudorese) Issa serrat semper sa bentana in antis de chenàre. Sassarese Edda sarra sempri lu balchoni primma di zinà. Sicilian Iḍḍa ncasa sempri a finesṭṛa prima ’i manciari â sira. Spanish (Ella) siempre cierra la ventana antes de cenar/comer. Tuscan Lei chiude sempre la finestra prima di cenà. Umbrian Lia chiude sempre la finestra prima de cenà. Venetian Eła ła sara/sera senpre ła fenestra vanti de diznar. Walloon Èle sere todi l'fignèsse divant d'soper.

Romance-based creoles and pidgins Haitian Creole Li toujou fèmen fenèt la avan li mange. Mauritian Creole Li touzour ferm lafnet avan (li) manze. Seychellois Creole Y pou touzour ferm lafnet aven y manze. Papiamento E muhe semper ta sera e bentana promé ku e kome. Kriolu Êl fechâ sempre janela antes de jantâ. Chavacano Ta cerrá él siempre con la ventana antes de cená. Palenquero Ele ta cerrá siempre ventana antes de cená.

Some of the divergence comes from semantic change: where the same root words have developed different meanings. For example, the Portuguese word fresta is descended from Latin fenestra "window" (and is thus cognate to French fenêtre, Italian finestra, Romanian fereastră and so on), but now means "skylight" and "slit". Cognates may exist but have become rare, such as hiniestra in Spanish, or dropped out of use entirely. The Spanish and Portuguese terms defenestrar meaning "to throw through a window" and fenestrado meaning "replete with windows" also have the same root, but are later borrowings from Latin.

Likewise, Portuguese also has the word cear, a cognate of Italian cenare and Spanish cenar, but uses it in the sense of "to have a late supper" in most varieties, while the preferred word for "to dine" is jantar (related to archaic Spanish yantar "to eat") because of semantic changes in the 19th century. Galician has both fiestra (from medieval fẽestra, the ancestor of standard Portuguese fresta) and the less frequently used ventá and xanela.

As an alternative to lei (originally the genitive form), Italian has the pronoun ella, a cognate of the other words for "she", but it is hardly ever used in speaking.

Spanish, Asturian, and Leonese ventana and Mirandese and Sardinian bentana come from Latin ventus "wind" (cf. English window, etymologically 'wind eye'), and Portuguese janela, Galician xanela, Mirandese jinela from Latin *ianuella "small opening", a derivative of ianua "door".

Sardinian balcone (alternative for ventàna/bentàna) comes from Old Italian and is similar to other Romance languages such as French balcon (from Italian balcone), Portuguese balcão, Romanian balcon, Spanish balcón, Catalan balcó and Corsican balconi (alternative for purtellu).

Along with Latin and a few extinct languages of ancient Italy, the Romance languages make up the Italic branch of the Indo-European family. [8] Identifying subdivisions of the Romance languages is inherently problematic, because most of the linguistic area is a dialect continuum, and in some cases political biases can come into play. A tree model is often used, but the selection of criteria results in different trees. Most classification schemes are, implicitly or not, historical and geographic, resulting in groupings such as Ibero- and Gallo-Romance. A major division can be drawn between Eastern and Western Romance, separated by the La Spezia-Rimini line.

The main subfamilies that have been proposed by Ethnologue within the various classification schemes for Romance languages are: [54]

- Italo-Western, the largest group, which includes languages such as Galician, Catalan, Portuguese, Italian, Spanish, and French.

- Eastern Romance, which includes Romanian and closely related languages.

- Southern Romance, which includes Sardinian and Corsican. This family is thought to have included the now-vanished Romance languages of North Africa (or at least, they appear to have evolved some phonological features and their vowels in the same way).

Ranking by distance

Another approach involves attempts to rank the distance of Romance languages from each other or from their common ancestor (i.e. ranking languages based on how conservative or innovative they are, although the same language may be conservative in some respects while innovative in others). By most measures, French is the most highly differentiated Romance language, although Romanian has changed the greatest amount of its vocabulary, while Italian [55] [56] [57] and Sardinian have changed the least. Standard Italian can be considered a "central" language, which is generally somewhat easy to understand to speakers of other Romance languages, whereas French and Romanian are peripheral and quite dissimilar from the rest of Romance. [8]

Pidgins, creoles, and mixed languages

Some Romance languages have developed varieties which seem dramatically restructured as to their grammars or to be mixtures with other languages. There are several dozens of creoles of French, Spanish, and Portuguese origin, some of them spoken as national languages and lingua franca in former European colonies.

Creoles of French:

- Antillean ( French Antilles, Saint Lucia, Dominica; majority native language)

- Haitian (one of Haiti's two official languages and majority native language)

- Louisiana (US)

- Mauritian ( lingua franca of Mauritius)

- Réunion (native language of Réunion)

- Seychellois ( Seychelles' official language)

Creoles of Spanish:

- Chavacano (in part of the Philippines)

- Palenquero (in part of Colombia)

Creoles of Portuguese:

- Angolar (regional language in São Tomé and Principe)

- Cape Verdean ( Cape Verde's national language and lingua franca; includes several distinct varieties)

- Daman and Diu Creole (regional language in India)

- Forro (regional language in São Tomé and Príncipe)

- Kristang ( Malaysia and Singapore)

- Kristi (regional language in India)

- Macanese ( Macau)

- Papiamento ( Dutch Antilles official language, majority native language, and lingua franca)

- Guinea-Bissau Creole ( Guinea-Bissau's national language and lingua franca)

Auxiliary and constructed languages

Latin and the Romance languages have also served as the inspiration and basis of numerous auxiliary and constructed languages, so-called "Neo-Romance languages". [58] [59]

The concept was first developed in 1903 by Italian mathematician Giuseppe Peano, under the title Latino sine flexione. [60] He wanted to create a naturalistic international language, as opposed to an autonomous constructed language like Esperanto or Volapük which were designed for maximal simplicity of lexicon and derivation of words. Peano used Latin as the base of his language because, as he described it, Latin had been the international scientific language until the end of the 18th century. [60] [61]

Other languages developed include Idiom Neutral (1902), Interlingue-Occidental (1922), Interlingua (1951) and Lingua Franca Nova (1998). The most famous and successful of these is Interlingua.[ citation needed] Each of these languages has attempted to varying degrees to achieve a pseudo-Latin vocabulary as common as possible to living Romance languages. Some languages have been constructed specifically for communication among speakers of Romance languages, the Pan-Romance languages.

There are also languages created for artistic purposes only, such as Talossan. Because Latin is a very well attested ancient language, some amateur linguists have even constructed Romance languages that mirror real languages that developed from other ancestral languages. These include Brithenig (which mirrors Welsh), Breathanach [62] (mirrors Irish), Wenedyk (mirrors Polish), Þrjótrunn (mirrors Icelandic), [63] and Helvetian (mirrors German). [64]

Sound changes

This article needs additional citations for

verification. (September 2023) |

Consonants

Significant sound changes affected the consonants of the Romance languages.

Apocope

There was a tendency to eliminate final consonants in Vulgar Latin, either by dropping them ( apocope) or adding a vowel after them ( epenthesis).

Many final consonants were rare, occurring only in certain prepositions (e.g. ad "towards", apud "at, near (a person)"), conjunctions (sed "but"), demonstratives (e.g. illud "that (over there)", hoc "this"), and nominative singular noun forms, especially of neuter nouns (e.g. lac "milk", mel "honey", cor "heart"). Many of these prepositions and conjunctions were replaced by others, while the nouns were regularized into forms based on their oblique stems that avoided the final consonants (e.g. *lacte, *mele, *core).

Final -m was dropped in Vulgar Latin. [65] Even in Classical Latin, final -am, -em, -um ( inflectional suffixes of the accusative case) were often elided in poetic meter, suggesting the m was weakly pronounced, probably marking the nasalisation of the vowel before it. This nasal vowel lost its nasalization in the Romance languages except in monosyllables, where it became /n/ e.g. Spanish quien < quem "whom", [65] French rien "anything" < rem "thing"; [66] note especially French and Catalan mon < meum "my (m.sg.)" which are derived from monosyllabic /meu̯m/ > */meu̯n/, /mun/, whereas Spanish disyllabic mío and Portuguese and Catalan monosyllabic meu are derived from disyllabic /ˈme.um/ > */ˈmeo/. [ citation needed]

As a result, only the following final consonants occurred in Vulgar Latin:

- Final -t in third-person singular verb forms, and -nt (later reduced in many languages to -n) in third-person plural verb forms. [67]

- Final -s (including -x) in a large number of morphological endings (verb endings -ās/-ēs/-īs/-is, -mus, -tis; nominative singular -us/-is; plural -ās/-ōs/-ēs) and certain other words (trēs "three", sex "six", crās "tomorrow", etc.).

- Final -n in some monosyllables (often from earlier -m).

- Final -r, -d in some prepositions (e.g. ad, per), which were clitics[ citation needed] that attached phonologically to the following word.

- Very occasionally, final -c, e.g. Occitan oc "yes" < hoc, Old French avuec "with" < apud hoc (although these instances were possibly protected by a final epenthetic vowel at one point).

Final -t was eventually lost in many languages, although this often occurred several centuries after the Vulgar Latin period. For example, the reflex of -t was dropped in Old French and Old Spanish only around 1100. In Old French, this occurred only when a vowel still preceded the t (generally /ə/ < Latin a). Hence amat "he loves" > Old French aime but venit "he comes" > Old French vient: the /t/ was never dropped and survives into Modern French in liaison, e.g. vient-il? "is he coming?" /vjɛ̃ti(l)/ (the corresponding /t/ in aime-t-il? is analogical, not inherited). Old French also kept the third-person plural ending -nt intact.

In Italo-Romance and the Eastern Romance languages, eventually all final consonants were either lost or protected by an epenthetic vowel, except for some articles and a few monosyllabic prepositions con, per, in. Modern Standard Italian still has very few consonant-final words, although Romanian has resurfaced them through later loss of final /u/ and /i/. For example, amās "you love" > ame > Italian ami; amant "they love" > *aman > Ital. amano. On the evidence of "sloppily written" Lombardic language documents, however, the loss of final /s/ in northern Italy did not occur until the 7th or 8th century, after the Vulgar Latin period, and the presence of many former final consonants is betrayed by the syntactic gemination (raddoppiamento sintattico) that they trigger. It is also thought that after a long vowel /s/ became /j/ rather than simply disappearing: nōs > noi "we", crās > crai "tomorrow" (southern Italy). [68] In unstressed syllables, the resulting diphthongs were simplified: canēs > */ˈkanej/ > cani "dogs"; amīcās > */aˈmikaj/ > amiche /aˈmike/ "(female) friends", where nominative amīcae should produce **amice rather than amiche (note masculine amīcī > amici not *amichi).

Central Western Romance languages eventually regained a large number of final consonants through the general loss of final /e/ and /o/, e.g. Catalan llet "milk" < lactem, foc "fire" < focum, peix "fish" < piscem. In French, most of these secondary final consonants (as well as primary ones) were lost before around 1700, but tertiary final consonants later arose through the loss of /ə/ < -a. Hence masculine frīgidum "cold" > Old French froit /'frwεt/ > froid /fʁwa/, feminine frīgidam > Old French froide /'frwεdə/ > froide /fʁwad/.

Palatalization

In Romance languages the term 'palatalization' is used to describe the phonetic evolution of velar stops preceding a front vowel and of consonant clusters involving yod or of the palatal approximant itself. [69] The process involving gestural blending and articulatory reinforcement, starting from Late Latin and Early Romance, generated a new series of consonants in Romance languages. [70]

Lenition

Stop consonants shifted by lenition in Vulgar Latin in some areas.

The voiced labial consonants /b/ and /w/ (represented by ⟨b⟩ and ⟨v⟩, respectively) both developed a fricative [β] as an intervocalic allophone. [71] This is clear from the orthography; in medieval times, the spelling of a consonantal ⟨v⟩ is often used for what had been a ⟨b⟩ in Classical Latin, or the two spellings were used interchangeably. In many Romance languages (Italian, French, Portuguese, Romanian, etc.), this fricative later developed into a /v/; but in others (Spanish, Galician, some Catalan and Occitan dialects, etc.) reflexes of /b/ and /w/ simply merged into a single phoneme. [72]

Several other consonants were "softened" in intervocalic position in Western Romance (Spanish, Portuguese, French, Northern Italian), but normally not phonemically in the rest of Italy (except some cases of "elegant" or Ecclesiastical words),[ clarification needed] nor apparently at all in Romanian. The dividing line between the two sets of dialects is called the La Spezia–Rimini Line and is one of the most important isogloss bundles of the Romance dialects. [73] The changes (instances of diachronic lenition resulting in phonological restructuring) are as follows: Single voiceless plosives became voiced: -p-, -t-, -c- > -b-, -d-, -g-. Subsequently, in some languages they were further weakened, either becoming fricatives or approximants, [β̞], [ð̞], [ɣ˕] (as in Spanish) or disappearing entirely (such as /t/ and /k/ lost between vowels in French, but /p/ > /v/). The following example shows progressive weakening of original /t/: e.g. vītam > Italian vita [ˈviːta], Portuguese vida [ˈvidɐ] (European Portuguese [ˈviðɐ]), Spanish vida [ˈbiða] (Southern Peninsular Spanish [ˈbi.a]), and French vie [vi]. Some scholars have speculated that these sound changes may be due in part to the influence of Continental Celtic languages, [74] while scholarship of the past few decades has proposed internal motivations. [75]

- The voiced plosives /d/ and /ɡ/ tended to disappear.

- The plain sibilant -s- [s] was also voiced to [z] between vowels, although in many languages its spelling has not changed. (In Spanish, intervocalic [z] was later devoiced back to [s]; [z] is only found as an allophone of /s/ before voiced consonants in Modern Spanish.)

- The double plosives became single: -pp-, -tt-, -cc-, -bb-, -dd-, -gg- > -p-, -t-, -c-, -b-, -d-, -g- in most languages. Subsequently, in some languages the voiced forms were further weakened, either becoming fricatives or approximants, [β̞], [ð̞], [ɣ˕] (as in Spanish). In French spelling, double consonants are merely etymological, except for -ll- after -i (pronounced [ij]), in most cases.

- The double sibilant -ss- [sː] also became phonetically and phonemically single [s], although in many languages its spelling has not changed. Double sibilant remains in some languages of Italy, like Italian, Sardinian, and Sicilian.

The sound /h/ was lost but later reintroduced into individual Romance languages. The so-called h aspiré "aspirated h" in French, now completely silent, was a borrowing from Frankish. In Spanish, word-initial /f/ changed to /h/ during its Medieval stage and was lost afterwards (for example farina > harina). [76] Romanian acquired it most likely from the adstrate. [77]

Consonant length is no longer phonemically distinctive in most Romance languages. However some languages of Italy (Italian, Sardinian, Sicilian, and numerous other varieties of central and southern Italy) do have long consonants like /bb/, /dd/, /ɡɡ/, /pp/, /tt/, /kk/, /ll/, /mm/, /nn/, /rr/, /ss/, etc., where the doubling indicates either actual length or, in the case of plosives and affricates, a short hold before the consonant is released, in many cases with distinctive lexical value: e.g. note /ˈnɔte/ (notes) vs. notte /ˈnɔtte/ (night), cade /ˈkade/ (s/he, it falls) vs. cadde /ˈkadde/ (s/he, it fell), caro /ˈkaro/ (dear, expensive) vs. carro /ˈkarro/ (cart, car). They may even occur at the beginning of words in Romanesco, Neapolitan, Sicilian and other southern varieties, and are occasionally indicated in writing, e.g. Sicilian cchiù (more), and ccà (here). In general, the consonants /b/, /ts/, and /dz/ are long at the start of a word, while the archiphoneme |R|[ dubious ] is realised as a trill /r/ in the same position. In much of central and southern Italy, the affricates /tʃ/ and /dʒ/ weaken synchronically to fricative [ʃ] and [ʒ] between vowels, while their geminate congeners do not, e.g. cacio /ˈkatʃo/ → [ˈkaːʃo] (cheese) vs. caccio /ˈkattʃo/ → [ˈkattʃo] (I chase). In Italian the geminates /ʃʃ/, /ɲɲ/, and /ʎʎ/ are pronounced as long [ʃʃ], [ɲɲ], and [ʎʎ] between vowels, but normally reduced to short following pause: lasciare 'let, leave' or la sciarpa 'the scarf' with [ʃʃ], but post-pausal sciarpa with [ʃ].

A few languages have regained secondary geminate consonants. The double consonants of Piedmontese exist only after stressed /ə/, written ë, and are not etymological: vëdde (Latin vidēre, to see), sëcca (Latin sicca, dry, feminine of sech). In standard Catalan and Occitan, there exists a geminate sound /lː/ written l·l (Catalan) or ll (Occitan), but it is usually pronounced as a simple sound in colloquial (and even some formal) speech in both languages.

Vowel prosthesis

In Late Latin a prosthetic vowel /i/ (lowered to /e/ in most languages) was inserted at the beginning of any word that began with /s/ (referred to as s impura) and a voiceless consonant (#sC- > isC-): [78]

- scrībere 'to write' > Sardinian iscribere, Spanish escribir, Portuguese escrever, Catalan escriure, Old French escri(v)re (mod. écrire);

- spatha "sword" > Sard ispada, Sp/Pg espada, Cat espasa, OFr espeḍe (modern épée);

- spiritus "spirit" > Sard ispìritu, Sp espíritu, Pg espírito, Cat esperit, French esprit;

- Stephanum "Stephen" > Sard Istèvene, Sp Esteban, Cat Esteve, Pg Estêvão, OFr Estievne (mod. Étienne);

- status "state" > Sard istadu, Sp/Pg estado, Cat estat, OFr estat (mod. état).

While Western Romance words fused the prosthetic vowel with the word, cognates in Eastern Romance and southern Italo-Romance did not, e.g. Italian scrivere, spada, spirito, Stefano, and stato, Romanian scrie, spată, spirit, Ștefan and stat. In Italian, syllabification rules were preserved instead by vowel-final articles, thus feminine spada as la spada, but instead of rendering the masculine *il stato, lo stato came to be the norm. Though receding at present, Italian once had a prosthetic /i/ maintaining /s/ syllable-final if a consonant preceded such clusters, so that 'in Switzerland' was in [i]Svizzera. Some speakers still use the prothetic [i] productively, and it is fossilized in a few set locutions such as in ispecie 'especially' or per iscritto 'in writing' (a form whose survival may have been buttressed in part by the word iscritto < Latin īnscrīptus).

Stressed vowels

Loss of vowel length, reorientation

| Classical | Sardinian | Eastern Romance | Proto- Romance |

Western Romance | Sicilian | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acad.1 | Roman | IPA | IPA | Acad.1 | IPA | IPA | ||

| ī | long i | /iː/ | /i/ | /i/ | ị | */i/ | /i/ | /i/ |

| ȳ | long y | /yː/ | ||||||

| i (ĭ) | short i | /ɪ/ | /e/ | į | */ɪ/ | /e/ | ||

| y (y̆) | short y | /ʏ/ | ||||||

| ē | long e | /eː/ | /ɛ/ | ẹ | */e/ | |||

| oe | oe | /oj/ > /eː/ | ||||||

| e (ĕ) | short e | /ɛ/ | /ɛ/ | ę | */ɛ/ | /ɛ/ | /ɛ/ | |

| ae | ae | /aj/ > /ɛː/ | ||||||

| ā | long a | /aː/ | /a/ | /a/ | a | */a/ | /a/ | /a/ |

| a (ă) | short a | /a/ | ||||||

| o (ŏ) | short o | /ɔ/ | /ɔ/ | /o/ | ǫ | */ɔ/ | /ɔ/ | /ɔ/ |

| ō | long o | /oː/ | ọ | */o/ | /o/ | /u/ | ||

| au (a few words) |

au | /aw/ > /ɔː/ | ||||||

| u (ŭ) | short u | /ʊ/ | /u/ | /u/ | ų | */ʊ/ | ||

| ū | long u | /uː/ | ụ | */u/ | /u/ | |||

| au (most words) |

au | /aw/ | /aw/ | /aw/ | au | */aw/ | /aw/ | /aw/ |

| 1 Traditional academic transcription in Latin and Romance studies, respectively. | ||||||||

One profound change that affected Vulgar Latin was the reorganisation of its vowel system. [79] Classical Latin had five short vowels, ă, ĕ, ĭ, ŏ, ŭ, and five long vowels, ā, ē, ī, ō, ū, each of which was an individual phoneme (see the table in the right, for their likely pronunciation in IPA), and four diphthongs, ae, oe, au and eu (five according to some authors, including ui). There were also long and short versions of y, representing the rounded vowel /y(ː)/ in Greek borrowings, which however probably came to be pronounced /i(ː)/ even before Romance vowel changes started.

There is evidence that in the imperial period all the short vowels except a differed by quality as well as by length from their long counterparts. [80] So, for example ē was pronounced close-mid /eː/ while ĕ was pronounced open-mid /ɛ/, and ī was pronounced close /iː/ while ĭ was pronounced near-close /ɪ/.

During the Proto-Romance period, phonemic length distinctions were lost. Vowels came to be automatically pronounced long in stressed, open syllables (i.e. when followed by only one consonant), and pronounced short everywhere else. This situation is still maintained in modern Italian: cade [ˈkaːde] "he falls" vs. cadde [ˈkadde] "he fell".

The Proto-Romance loss of phonemic length originally produced a system with nine different quality distinctions in monophthongs, where only original /a aː/ had merged. [81] Soon, however, many of these vowels coalesced:

- The simplest outcome was in Sardinian, [82] where the former long and short vowels in Latin simply coalesced, e.g. /ɛ eː/ > /ɛ/, /ɪ iː/ > /i/: This produced a simple five-vowel system /a ɛ i ɔ u/. [83]

- In most areas, however (technically, the Italo-Western languages), the near-close vowels /ɪ ʊ/ lowered and merged into the high-mid vowels /e o/. As a result, Latin pira "pear" and vēra "true", came to rhyme (e.g. Italian and Spanish pera, vera, and Old French poire, voire). Similarly, Latin nucem (from nux "nut") and vōcem (from vōx "voice") become Italian noce, voce, Portuguese noz, voz, and French noix, voix. This produced a seven-vowel system /a ɛ e i ɔ o u/, still maintained in conservative languages such as Italian and Portuguese, and lightly transformed in Spanish (where /ɛ/ > /je/, /ɔ/ > /we/).

- In the Eastern Romance languages (particularly, Romanian), the front vowels /ĕ ē ĭ ī/ evolved as in the majority of languages, but the back vowels /ɔ oː ʊ uː/ evolved as in Sardinian. This produced an unbalanced six-vowel system: /a ɛ e i o u/. In modern Romanian, this system has been significantly transformed, with /ɛ/ > /je/ and with new vowels /ə ɨ/ evolving, leading to a balanced seven-vowel system with central as well as front and back vowels: /a e i ə ɨ o u/. [84]

- Sicilian is sometimes described as having its own distinct vowel system. In fact, Sicilian passed through the same developments as the main bulk of Italo-Western languages. Subsequently, however, high-mid vowels (but not low-mid vowels) were raised in all syllables, stressed and unstressed; i.e. /e o/ > /i u/. The result is a five-vowel /a ɛ i ɔ u/. [83]

Further variants are found in southern Italy and Corsica, which also boasts a completely distinct system.

| Classical Latin | Proto-Romance | Senisese | Castel-mezzano | Neapolitan | Sicilian | Verbi-carese | Caro-vignese | Nuorese Sardinian | Southern Corsican | Taravo Corsican | Northern Corsican | Cap de Corse |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ā | */a/ | /a/ | /a/ | /a/ | /a/ | /a/ | /a/ | /a/ | /a/ | /a/ | /a/ | /a/ |

| ă | ||||||||||||

| au | */aw/ | /ɔ/? | /o/? | /ɔ/? | /ɔ/? | /ɔ/? | /ɔ/? | /ɔ/ | /o/? | /ɔ/? | /o/? | |

| ĕ, ae | */ɛ/ | /ɛ/ | /e/ | /ɛ/ | /ɛ/ | /ɛ/ | /ɛ/ | /ɛ/ | /e/ | /e/ | /ɛ/ | /e/ (/ɛ/) |

| ē, oe | */e/ | /e/ | /i/ | /ɪ/ (/ɛ/) | /e/ | /e/ | ||||||

| ĭ | */ɪ/ | /i/ | /ɪ/ | /i/ | /i/ | /ɛ/ | ||||||

| ī | */i/ | /i/ | /i/ | /i/ | /i/ | /i/ | /i/ | |||||

| ŏ | */ɔ/ | /ɔ/ | /o/ | /ɔ/ | /ɔ/ | /ɔ/ | /ɔ/ | /ɔ/ | /o/ | /o/ | /ɔ/ | /o/ |

| ō, (au) | */o/ | /o/ | /u/ | /ʊ/ (/ɔ/) | /o/ | |||||||

| ŭ | */ʊ/ | /u/ | /u/ | /ʊ/ | /u/ | /u/ | /ɔ/ | |||||

| ū | */u/ | /u/ | /u/ | /u/ | /u/ | /u/ |

The Sardinian-type vowel system is also found in a small region belonging to the Lausberg area (also known as Lausberg zone; compare Neapolitan language § Distribution) of southern Italy, in southern Basilicata, and there is evidence that the Romanian-type "compromise" vowel system was once characteristic of most of southern Italy, [85] although it is now limited to a small area in western Basilicata centered on the Castelmezzano dialect, the area being known as Vorposten, the German word for 'outpost'. The Sicilian vowel system, now generally thought to be a development based on the Italo-Western system, is also represented in southern Italy, in southern Cilento, Calabria and the southern tip of Apulia, and may have been more widespread in the past. [86]

The greatest variety of vowel systems outside of southern Italy is found in Corsica, where the Italo-Western type is represented in most of the north and center and the Sardinian type in the south, as well as a system resembling the Sicilian vowel system (and even more closely the Carovignese system) in the Cap Corse region; finally, in between the Italo-Western and Sardinian system is found, in the Taravo region, a unique vowel system that cannot be derived from any other system, which has reflexes like Sardinian for the most part, but the short high vowels of Latin are uniquely reflected as mid-low vowels. [87]

The Proto-Romance allophonic vowel-length system was phonemicized in the Gallo-Romance languages as a result of the loss of many final vowels. Some northern Italian languages (e.g. Friulian) still maintain this secondary phonemic length, but most languages dropped it by either diphthongizing or shortening the new long vowels.

French phonemicized a third vowel length system around AD 1300 as a result of the sound change /VsC/ > /VhC/ > /VːC/ (where V is any vowel and C any consonant). This vowel length began to be lost in Early Modern French, but the long vowels are still usually marked with a circumflex (and continue to be distinguished regionally, chiefly in Belgium). A fourth vowel length system, still non-phonemic, has now arisen: All nasal vowels as well as the oral vowels /ɑ o ø/ (which mostly derive from former long vowels) are pronounced long in all stressed closed syllables, and all vowels are pronounced long in syllables closed by the voiced fricatives /v z ʒ ʁ vʁ/. This system in turn has been phonemicized in some varieties (e.g. Haitian Creole), as a result of the loss of final /ʁ/.[ citation needed]

Latin diphthongs

The Latin diphthongs ae and oe, pronounced /aj/ and /oj/ in earlier Latin, were early on monophthongized. [88]

ae became /ɛː/ by[ citation needed] the 1st century a.d. at the latest. Although this sound was still distinct from all existing vowels, the neutralization of Latin vowel length eventually caused its merger with /ɛ/ < short e: e.g. caelum "sky" > French ciel, Spanish/Italian cielo, Portuguese céu /sɛw/, with the same vowel as in mele "honey" > French/Spanish miel, Italian miele, Portuguese mel /mɛl/. Some words show an early merger of ae with /eː/, as in praeda "booty" > *prēda /preːda/ > French proie (vs. expected **priée), Italian preda (not **prieda) "prey"; or faenum "hay" > *fēnum [feːnũ] > Spanish heno, French foin (but Italian fieno /fjɛno/).

oe generally merged with /eː/: poenam "punishment" > Romance */pena/ > Spanish/Italian pena, French peine; foedus "ugly" > Romance */fedo/ > Spanish feo, Portuguese feio. There are relatively few such outcomes, since oe was rare in Classical Latin (most original instances had become Classical ū, as in Old Latin oinos "one" > Classical ūnus [89]) and so oe was mostly limited to Greek loanwords, which were typically learned (high-register) terms.

au merged with ō /oː/ in the popular speech of Rome already by the 1st century b.c.[ citation needed] A number of authors remarked on this explicitly, e.g. Cicero's taunt that the populist politician Publius Clodius Pulcher had changed his name from Claudius to ingratiate himself with the masses. This change never penetrated far from Rome, however, and the pronunciation /au/ was maintained for centuries in the vast majority of Latin-speaking areas, although it eventually developed into some variety of o in many languages. For example, Italian and French have /ɔ/ as the usual reflex, but this post-dates diphthongization of /ɔ/ and the French-specific palatalization /ka/ > /tʃa/ (hence causa > French chose, Italian cosa /kɔza/ not **cuosa). Spanish has /o/, but Portuguese spelling maintains ⟨ou⟩, which has developed to /o/ (and still remains as /ou/ in some dialects, and /oi/ in others). [90] Occitan, Dalmatian, Sardinian, and many other minority Romance languages still have /au/ while in Romanian it underwent diaresis like in aurum > aur (a-ur). [91] A few common words, however, show an early merger with ō /oː/, evidently reflecting a generalization of the popular Roman pronunciation:[ citation needed] e.g. French queue, Italian coda /koda/, Occitan co(d)a, Romanian coadă (all meaning "tail") must all derive from cōda rather than Classical cauda. [92] Similarly, Spanish oreja, Portuguese orelha, French oreille, Romanian ureche, and Sardinian olícra, orícla "ear" must derive from ōric(u)la rather than Classical auris (Occitan aurelha was probably influenced by the unrelated ausir < audīre "to hear"), and the form oricla is in fact reflected in the Appendix Probi.

Further developments

Metaphony

An early process that operated in all Romance languages to varying degrees was metaphony (vowel mutation), conceptually similar to the umlaut process so characteristic of the Germanic languages. Depending on the language, certain stressed vowels were raised (or sometimes diphthongized) either by a final /i/ or /u/ or by a directly following /j/. Metaphony is most extensive in the Italo-Romance languages, and applies to nearly all languages in Italy; however, it is absent from Tuscan, and hence from standard Italian. In many languages affected by metaphony, a distinction exists between final /u/ (from most cases of Latin -um) and final /o/ (from Latin -ō, -ud and some cases of -um, esp. masculine "mass" nouns), and only the former triggers metaphony.

Some examples:

- In Servigliano in the Marche of Italy, stressed /ɛ e ɔ o/ are raised to /e i o u/ before final /i/ or /u/: [93] /ˈmetto/ "I put" vs. /ˈmitti/ "you put" (< *metti < *mettes < Latin mittis); /moˈdɛsta/ "modest (fem.)" vs. /moˈdestu/ "modest (masc.)"; /ˈkwesto/ "this (neut.)" (< Latin eccum istud) vs. /ˈkwistu/ "this (masc.)" (< Latin eccum istum).

- Calvallo in Basilicata, southern Italy, is similar, but the low-mid vowels /ɛ ɔ/ are diphthongized to /je wo/ rather than raised: [94] /ˈmette/ "he puts" vs. /ˈmitti/ "you put", but /ˈpɛnʒo/ "I think" vs. /ˈpjenʒi/ "you think".

- Metaphony also occurs in most northern Italian dialects, but only by (usually lost) final *i; apparently, final *u was lowered to *o (usually lost) before metaphony could take effect.

- Some of the Astur-Leonese languages in northern Spain have the same distinction between final /o/ and /u/ [95] as in the Central-Southern Italian languages, [96] with /u/ triggering metaphony. [97] The plural of masculine nouns in these dialects ends in -os, which does not trigger metaphony, unlike in the singular (vs. Italian plural -i, which does trigger metaphony).

- Sardinian has allophonic raising of mid vowels /ɛ ɔ/ to [e o] before final /i/ or /u/. This has been phonemicized in the Campidanese dialect as a result of the subsequent raising of final /e o/ to /i u/.

- Raising of /ɔ/ to /o/ occurs sporadically in Portuguese in the masculine singular, e.g. porco /ˈporku/ "pig" vs. porcos /ˈpɔrkus/ "pig". It is thought that Galician-Portuguese at one point had singular /u/ vs. plural /os/, exactly as in modern Astur-Leonese. [96]

- In all of the Western Romance languages, final /i/ (primarily occurring in the first-person singular of the preterite) raised mid-high /e o/ to /i u/, e.g. Portuguese fiz "I did" (< *fidzi < *fedzi < Latin fēcī) vs. fez "he did" (< *fedze < Latin fēcit). Old Spanish similarly had fize "I did" vs. fezo "he did" (-o by analogy with amó "he loved"), but subsequently generalized stressed /i/, producing modern hice "I did" vs. hizo "he did". The same thing happened prehistorically in Old French, yielding fis "I did", fist "he did" (< *feist < Latin fēcit).

Diphthongization

A number of languages diphthongized some of the free vowels, especially the open-mid vowels /ɛ ɔ/: [98]

- Spanish consistently diphthongized all open-mid vowels /ɛ ɔ/ > /je we/ except for before certain palatal consonants (which raised the vowels to close-mid before diphthongization took place).

- Eastern Romance languages similarly diphthongized /ɛ/ to /je/ (the corresponding vowel /ɔ/ did not develop from Proto-Romance).

- Italian diphthongized /ɛ/ > /jɛ/ and /ɔ/ > /wɔ/ in open syllables (in the situations where vowels were lengthened in Proto-Romance), the most salient exception being /ˈbɛne/ bene 'well', perhaps due to the high frequency of apocopated ben (e.g. ben difficile 'quite difficult', ben fatto 'well made' etc.).

- French similarly diphthongized /ɛ ɔ/ in open syllables (when lengthened), along with /a e o/: /aː ɛː eː ɔː oː/ > /aɛ iɛ ei uɔ ou/ > middle OF /e je ɔi we eu/ > modern /e je wa œ ~ ø œ ~ ø/.

- French also diphthongized /ɛ ɔ/ before palatalized consonants, especially /j/. Further development was as follows: /ɛj/ > /iej/ > /i/; /ɔj/ > /uoj/ > early OF /uj/ > modern /ɥi/.

- Catalan diphthongized /ɛ ɔ/ before /j/ from palatalized consonants, just like French, with similar results: /ɛj/ > /i/, /ɔj/ > /uj/.

These diphthongization had the effect of reducing or eliminating the distinctions between open-mid and close-mid vowels in many languages. In Spanish and Romanian, all open-mid vowels were diphthongized, and the distinction disappeared entirely. [99] Portuguese is the most conservative in this respect, keeping the seven-vowel system more or less unchanged (but with changes in particular circumstances, e.g. due to metaphony). Other than before palatalized consonants, Catalan keeps /ɔ o/ intact, but /ɛ e/ split in a complex fashion into /ɛ e ə/ and then coalesced again in the standard dialect ( Eastern Catalan) in such a way that most original /ɛ e/ have reversed their quality to become /e ɛ/.

In French and Italian, the distinction between open-mid and close-mid vowels occurred only in closed syllables. Standard Italian more or less maintains this. In French, /e/ and /ɛ/ merged by the twelfth century or so, and the distinction between /ɔ/ and /o/ was eliminated without merging by the sound changes /u/ > /y/, /o/ > /u/. Generally this led to a situation where both [e,o] and [ɛ,ɔ] occur allophonically, with the close-mid vowels in open syllables and the open-mid vowels in closed syllables. In French, both [e/ɛ] and [o/ɔ] were partly rephonemicized: Both /e/ and /ɛ/ occur in open syllables as a result of /aj/ > /ɛ/, and both /o/ and /ɔ/ occur in closed syllables as a result of /al/ > /au/ > /o/.

Old French also had numerous falling diphthongs resulting from diphthongization before palatal consonants or from a fronted /j/ originally following palatal consonants in Proto-Romance or later: e.g. pācem /patsʲe/ "peace" > PWR */padzʲe/ (lenition) > OF paiz /pajts/; *punctum "point" > Gallo-Romance */ponʲto/ > */pojɲto/ (fronting) > OF point /põjnt/. During the Old French period, preconsonantal /l/ [ɫ] vocalized to /w/, producing many new falling diphthongs: e.g. dulcem "sweet" > PWR */doltsʲe/ > OF dolz /duɫts/ > douz /duts/; fallet "fails, is deficient" > OF falt > faut "is needed"; bellus "beautiful" > OF bels [bɛɫs] > beaus [bɛaws]. By the end of the Middle French period, all falling diphthongs either monophthongized or switched to rising diphthongs: proto-OF /aj ɛj jɛj ej jej wɔj oj uj al ɛl el il ɔl ol ul/ > early OF /aj ɛj i ej yj oj yj aw ɛaw ew i ɔw ow y/ > modern spelling ⟨ai ei i oi ui oi ui au eau eu i ou ou u⟩ > mod. French /ɛ ɛ i wa ɥi wa ɥi o o ø i u u y/.[ citation needed]

Nasalization

In both French and Portuguese, nasal vowels eventually developed from sequences of a vowel followed by a nasal consonant (/m/ or /n/). Originally, all vowels in both languages were nasalized before any nasal consonants, and nasal consonants not immediately followed by a vowel were eventually dropped. In French, nasal vowels before remaining nasal consonants were subsequently denasalized, but not before causing the vowels to lower somewhat, e.g. dōnat "he gives" > OF dune /dunə/ > donne /dɔn/, fēminam > femme /fam/. Other vowels remained nasalized, and were dramatically lowered: fīnem "end" > fin /fɛ̃/ (often pronounced [fæ̃]); linguam "tongue" > langue /lɑ̃ɡ/; ūnum "one" > un /œ̃/, /ɛ̃/.

In Portuguese, /n/ between vowels was dropped, and the resulting hiatus eliminated through vowel contraction of various sorts, often producing diphthongs: manum, *manōs > PWR *manu, ˈmanos "hand(s)" > mão, mãos /mɐ̃w̃, mɐ̃w̃s/; canem, canēs "dog(s)" > PWR *kane, ˈkanes > *can, ˈcanes > cão, cães /kɐ̃w̃, kɐ̃j̃s/; ratiōnem, ratiōnēs "reason(s)" > PWR *raˈdʲzʲone, raˈdʲzʲones > *raˈdzon, raˈdzones > razão, razões /χaˈzɐ̃w̃, χaˈzõj̃s/ (Brazil), /ʁaˈzɐ̃ũ, ʁɐˈzõj̃ʃ/ (Portugal). Sometimes the nasalization was eliminated: lūna "moon" > Galician-Portuguese lũa > lua; vēna "vein" > Galician-Portuguese vẽa > veia. Nasal vowels that remained actually tend to be raised (rather than lowered, as in French): fīnem "end" > fim /fĩ/; centum "hundred" > PWR tʲsʲɛnto > cento /ˈsẽtu/; pontem "bridge" > PWR pɔnte > ponte /ˈpõtʃi/ (Brazil), /ˈpõtɨ/ (Portugal). [100]

Romanian shows evidence of past nasalization phenomena, the loss of palatal nasal [ɲ] in vie < Lat. vinia, and the rhotacism of intervocalic /n/ in words like mărunt < Lat. minutu for example. The effect of nasalization is observed in vowel closing to /i ɨ u/ before single /n/ and nasal+consonant clusters. Latin /nn/ and /m/ did not cause the same effect. [101]

Front-rounded vowels

Characteristic of the Gallo-Romance and Rhaeto-Romance languages are the front rounded vowels /y ø œ/. All of these languages, with the exception of Catalan, show an unconditional change /u/ > /y/, e.g. lūnam > French lune /lyn/, Occitan /ˈlyno/. Many of the languages in Switzerland and Italy show the further change /y/ > /i/. Also very common is some variation of the French development /ɔː oː/ (lengthened in open syllables) > /we ew/ > /œ œ/, with mid back vowels diphthongizing in some circumstances and then re-monophthongizing into mid-front rounded vowels. (French has both /ø/ and /œ/, with /ø/ developing from /œ/ in certain circumstances.)

Unstressed vowels

| Latin | Proto- Romance |

Stressed | Non-final unstressed |

Final-unstressed | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | Later Italo- Romance |

Later Western- Romance |

Gallo- Romance |

Primitive French | |||||

| Acad.1 | IPA | IPA | |||||||

| a, ā | a | */a/ | /a/ | /a/ | /a/ | /ə/ | |||

| e, ae | ę | */ɛ/ | /ɛ/ | /e/ | /e/ | /e/ | /e/ | ∅; /e/ (prop) | ∅; /ə/ (prop) |

| ē, oe | ẹ | */e/ | /e/ | ||||||

| i, y | į | */ɪ/ | |||||||

| ī, ȳ | ị | */i/ | /i/ | /i/ | /i/ | ||||

| o | ǫ | */ɔ/ | /ɔ/ | /o/ | /o/ | /o/ | |||

| ō, (au) | ọ | */o/ | /o/ | ||||||

| u | ų | */ʊ/ | /u/ | ||||||

| ū | ụ | */u/ | /u/ | ||||||

| au (most words) |

au | */aw/ | /aw/ | N/A | |||||

| 1 Traditional academic transcription in Romance studies. | |||||||||

There was more variability in the result of the unstressed vowels. Originally in Proto-Romance, the same nine vowels developed in unstressed as stressed syllables, and in Sardinian, they coalesced into the same five vowels in the same way.

In Italo-Western Romance, however, vowels in unstressed syllables were significantly different from stressed vowels, with yet a third outcome for final unstressed syllables. In non-final unstressed syllables, the seven-vowel system of stressed syllables developed, but then the low-mid vowels /ɛ ɔ/ merged into the high-mid vowels /e o/. This system is still preserved, largely or completely, in all of the conservative Romance languages (e.g. Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan).

In final unstressed syllables, results were somewhat complex. One of the more difficult issues is the development of final short -u, which appears to have been raised to /u/ rather than lowered to /o/, as happened in all other syllables. However, it is possible that in reality, final /u/ comes from long *-ū < -um, where original final -m caused vowel lengthening as well as nasalization. Evidence of this comes from Rhaeto-Romance, in particular Sursilvan, which preserves reflexes of both final -us and -um, and where the latter, but not the former, triggers metaphony. This suggests the development -us > /ʊs/ > /os/, but -um > /ũː/ > /u/. [102]

The original five-vowel system in final unstressed syllables was preserved as-is in some of the more conservative central Italian languages, but in most languages there was further coalescence:

- In Tuscan (including standard Italian), final /u/ merged into /o/.

- In the Western Romance languages, final /i/ eventually merged into /e/ (although final /i/ triggered metaphony before that, e.g. Spanish hice, Portuguese fiz "I did" < *fize < Latin fēcī). Conservative languages like Spanish largely maintain that system, but drop final /e/ after certain single consonants, e.g. /r/, /l/, /n/, /d/, /z/ (< palatalized c). The same situation happened in final /u/ that merged into /o/ in Spanish.

- In the Gallo-Romance languages (part of Western Romance), final /o/ and /e/ were dropped entirely unless that produced an impossible final cluster (e.g. /tr/), in which case a "prop vowel" /e/ was added. This left only two final vowels: /a/ and prop vowel /e/. Catalan preserves this system.

- Loss of final stressless vowels in Venetian shows a pattern intermediate between Central Italian and the Gallo-Italic branch, and the environments for vowel deletion vary considerably depending on the dialect. In the table above, final /e/ is uniformly absent in mar, absent in some dialects in part(e) /part(e)/ and set(e) /sɛt(e)/, but retained in mare (< Latin mātrem) as a relic of the earlier cluster *dr.

- In primitive Old French (one of the Gallo-Romance languages), these two remaining vowels merged into /ə/.

Various later changes happened in individual languages, e.g.:

- In French, most final consonants were dropped, and then final /ə/ was also dropped. The /ə/ is still preserved in spelling as a final silent -e, whose main purpose is to signal that the previous consonant is pronounced, e.g. port "port" /pɔʁ/ vs. porte "door" /pɔʁt/. These changes also eliminated the difference between singular and plural in most words: ports "ports" (still /pɔʁ/), portes "doors" (still /pɔʁt/). Final consonants reappear in liaison contexts (in close connection with a following vowel-initial word), e.g. nous [nu] "we" vs. nous avons [nu.za.ˈvɔ̃] "we have", il fait [il.fɛ] "he does" vs. fait-il ? [fɛ.til] "does he?".

- In Portuguese, final unstressed /o/ and /u/ were apparently preserved intact for a while, since final unstressed /u/, but not /o/ or /os/, triggered metaphony (see above). Final-syllable unstressed /o/ was raised in preliterary times to /u/, but always still written ⟨o⟩. At some point (perhaps in late Galician-Portuguese), final-syllable unstressed /e/ was raised to /i/ (but still written ⟨e⟩); this remains in Brazilian Portuguese, but has developed to /ɨ/ in northern and central European Portuguese.

- In Catalan, final unstressed /as/ > /es/. In many dialects, unstressed /o/ and /u/ merge into /u/ as in Portuguese, and unstressed /a/ and /e/ merge into /ə/. However, some dialects preserve the original five-vowel system, most notably standard Valencian.

| English | Latin | Proto-Italo- Western1 |

Conservative Central Italian1 |

Italian | Portuguese | Spanish | Catalan | Old French | Modern French |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a, e, i, o, u | a, e, i, o, u | a, e, i, o | a, e/-, o | a, -/e | e, -/e | ||||

| one (fem.) | ūnam | [ˈuna] | una | uma | una | une | |||

| door | portam | [ˈpɔrta] | porta | puerta | porta | porte | |||

| seven | septem | [ˈsɛtte] | sette | sete | siete | set | sept | ||

| sea | mare | [ˈmare] | mare | mar | mer | ||||

| peace | pācem | [ˈpatʃe] | pace | paz | pau | paiz | paix | ||

| part | partem | [ˈparte] | parte | part | |||||

| truth | veritātem | [veriˈtate] | verità | verdade | verdad | veritat | verité | vérité | |

| mother | mātrem | [ˈmatre] | matre | madre | mãe | madre | mare | meḍre | mère |

| twenty | vīgintī | [veˈenti] | vinti | venti | vinte | veinte | vint | vingt | |

| four | quattuor | [ˈkwattro] | quattro | quatro | cuatro | quatre | |||

| eight | octō | [ˈɔkto] | otto | oito | ocho | vuit | huit | ||

| when | quandō | [ˈkwando] | quando | cuando | quan | quant | quand | ||

| fourth | quartum | [ˈkwartu] | quartu | quarto | cuarto | quart | |||

| one (masc.) | ūnum | [ˈunu] | unu | uno | um | uno | un | ||

| port | portum | [ˈpɔrtu] | portu | porto | puerto | port | |||

Intertonic vowels

The so-called intertonic vowels are word-internal unstressed vowels, i.e. not in the initial, final, or tonic (i.e. stressed) syllable, hence intertonic. Intertonic vowels were the most subject to loss or modification. Already in Vulgar Latin intertonic vowels between a single consonant and a following /r/ or /l/ tended to drop: vétulum "old" > veclum > Dalmatian vieklo, Sicilian vecchiu, Portuguese velho. But many languages ultimately dropped almost all intertonic vowels.

Generally, those languages south and east of the La Spezia–Rimini Line (Romanian and Central-Southern Italian) maintained intertonic vowels, while those to the north and west (Western Romance) dropped all except /a/. Standard Italian generally maintained intertonic vowels, but typically raised unstressed /e/ > /i/. Examples:

- septimā́nam "week" > Italian settimana, Romanian săptămână vs. Spanish/Portuguese semana, French semaine, Occitan/Catalan setmana, Piedmontese sman-a

- quattuórdecim "fourteen" > Italian quattordici, Venetian cuatòrdexe, Lombard/Piedmontese quatòrdes, vs. Spanish catorce, Portuguese/French quatorze

- metipsissimus [103] > medipsimus /medíssimos/ ~ /medéssimos/ "self" [104] > Italian medésimo vs. Venetian medemo, Lombard medemm, Old Spanish meísmo, meesmo (> modern mismo), Galician-Portuguese meesmo (> modern mesmo), Old French meḍisme (> later meïsme > MF mesme > modern même) [105]

- bonitā́tem "goodness" > Italian bonità ~ bontà, Romanian bunătate but Spanish bondad, Portuguese bondade, French bonté

- collocā́re "to position, arrange" > Italian coricare vs. Spanish colgar "to hang", Romanian culca "to lie down", French coucher "to lay sth on its side; put s.o. to bed"

- commūnicā́re "to take communion" > Romanian cumineca vs. Portuguese comungar, Spanish comulgar, Old French comungier

- carricā́re "to load (onto a wagon, cart)" > Portuguese/Catalan carregar vs. Spanish/Occitan cargar "to load", French charger, Lombard cargà/caregà, Venetian carigar/cargar(e) "to load", Romanian încărca

- fábricam "forge" > /*fawrɡa/ > Spanish fragua, Portuguese frágua, Occitan/Catalan farga, French forge

- disjējūnā́re "to break a fast" > *disjūnā́re > Old French disner "to have lunch" > French dîner "to dine" (but *disjū́nat > Old French desjune "he has lunch" > French (il) déjeune "he has lunch")

- adjūtā́re "to help" > Italian aiutare, Romanian ajuta but French aider, Lombard aidà/aiuttà (Spanish ayudar, Portuguese ajudar based on stressed forms, e.g. ayuda/ajuda "he helps"; cf. Old French aidier "to help" vs. aiue "he helps")

Portuguese is more conservative in maintaining some intertonic vowels other than /a/: e.g. *offerḗscere "to offer" > Portuguese oferecer vs. Spanish ofrecer, French offrir (< *offerīre). French, on the other hand, drops even intertonic /a/ after the stress: Stéphanum "Stephen" > Spanish Esteban but Old French Estievne > French Étienne. Many cases of /a/ before the stress also ultimately dropped in French: sacraméntum "sacrament" > Old French sairement > French serment "oath".

Writing systems

The Romance languages for the most part have continued to use the Latin alphabet while adapting it to their evolution. One exception was Romanian, where before the nineteenth century, the Romanian Cyrillic alphabet was used due to Slavic influence after the Roman retreat. A Cyrillic alphabet was also used for Romanian (then called Moldovan) in the USSR. The non-Christian populations of Spain also used the scripts of their religions ( Arabic and Hebrew) to write Romance languages such as Judaeo-Spanish and Mozarabic in aljamiado.

Letters

The classical Latin alphabet of 23 letters – A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, V, X, Y, Z – was modified and augmented in various ways to yield the spelling systems of the Romance languages. In particular, the single Latin letter V split into V (consonant) and U (vowel), and the letter I split into I and J. The Latin letter K and the new letter W, which came to be widely used in Germanic languages, are seldom used in most Romance languages – mostly for unassimilated foreign names and words. Indeed, in Italian prose kilometro is properly chilometro. Portuguese and Catalan eschew importation of "foreign" letters more than most languages. Thus Wikipedia is Viquipèdia in Catalan but Wikipedia in Spanish; chikungunya, sandwich, kiwi are chicungunha, sanduíche, quiuí in Portuguese but chikunguña, sándwich, kiwi in Spanish.

While most of the 23 basic Latin letters have maintained their phonetic value, for some of them it has diverged considerably; and the new letters added since the Middle Ages have been put to different uses in different scripts. Some letters, notably H and Q, have been variously combined in digraphs or trigraphs (see below) to represent phonetic phenomena that could not be recorded with the basic Latin alphabet, or to get around previously established spelling conventions. Most languages added auxiliary marks ( diacritics) to some letters, for these and other purposes.

The spelling systems of most Romance languages are fairly simple, and consistent within any language. Spelling rules are typically phonemic (as opposed to being strictly phonetic); as a result of this, the actual pronunciation of standard written forms can vary substantially according to the speaker's accent (which may differ by region) or the position of a sound in the word or utterance ( allophony).