The Nue (鵺, 鵼, 恠鳥, or 奴延鳥) is a legendary yōkai or mononoke.

Appearance

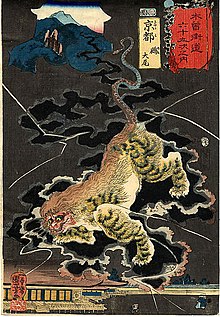

In the Tale of Heike, it is described as a Japanese chimera having the head of a monkey, the limbs of a tiger, the body of a Japanese raccoon dog, and the front half of a snake for a tail. In other writings nothing is stated about its torso, so it is sometimes depicted to have the torso of a tiger. The Genpei Jōsuiki describes it as having the back of a tiger, the limbs of a tanuki, the tail of a fox, the head of a cat, and the torso of a chicken. [1] Due to its appearance, it is sometimes referred to as a Japanese chimera. [2]

It is said to make terribly eerie bird cry "hyoo hyoo" noises that resemble that of the scaly thrush. In the movie Akuryōtō (originally by Seishi Yokomizo), the catchphrase "nights where the nue cry are dreadful" refers to this fact. The nue is also said to have the ability of shape-shifting, often into the form of a black cloud that can fly. The yokai is also thought to be nocturnal as most of its sightings happen at night. Its name written in kanji translates to night and bird. [3]

History

The nue is thought to have started appearing in the late Heian period. For a more precise dating, different sources claim different periods, like the Emperor Nijō period, the Emperor Konoe period, the Emperor Go-Shirakawa period, or the Emperor Toba period. [4]

The visual appearance may be a combination of the animals in the Sexagenary cycle, with a northeast Tiger, a southeast Snake, a southwest Monkey, and a northwest Qian ( Dog and Wild Boar).

Originally, the nue were stated to be a bird that resembles the green pheasant, [5] but their precise identity is unknown. The 夜 within the 鵺 character is phonetic component and thus does not carry a meaning with it. The character 鵼 (kou or kuu) is determined to be a kind of strange bird. [5] Due to the use of Man'yōgana, the historical spelling is known to have been nuye. At this early time, although, it had a different semantic meaning. It referred to a bird known as White's thrush.

In Japan, they are considered a bird that makes cries at night, and the word can be seen in the Kojiki and the Man'yōshū. [4] The owner of this crying voice was traditionally described as a yellow-red bird as big as a Columbidae, [5] but nowadays there is the accepted theory that it is the scaly thrush. [4] Since the people of the Heian Period regarded the sorrowful sounding voices of this bird as an ill omen, they were considered to be a wicked bird, [6] and it is said that when the emperor or nobles heard its crying voice, they would make prayers that nothing disastrous would happen. [4]

The monster in the Heike Monogatari, in the end, was merely "something that cries with the voice of a nue, its true nature unknown", and was not given a name. But nowadays, this particularly famous monster is usually identified as a "nue".

In a derived sense the word "nue" is also used to refer to entities of unknown true form.

The noh play Nue, by Zeami Motokiyo, based on the setsuwa, the Heike Monogatari. They are a regular feature of the Kiri-noh (fifth performance of a noh).

Nue-harai Matsuri ("Nue-warding festival") – a festival performed every year on January 28 at the Izunagaoka Onsen in Izunokuni, Shizuoka Prefecture. Among other things the nue-odori (nue-dance) and the mochi-maki ( mochi-scattering) are performed. [7]

At Osaka Harbor, the Nue is used as a motif in its emblem design. From the legend of Nuezuka, it was selected for its relation to Osaka bay. [8] [9]

The slaying of the Nue

The Heike Monogatari and the Settsu Meisho Zue from the Settsu Province, tell the following tale of the killing of the Nue:

In the closing years of the Heian period, at the place where the emperor ( Emperor Konoe) lived, the Seiryō-den, there appeared a cloud of black smoke along with an eerie resounding crying voice, making Emperor Nijō quite afraid. Subsequently, the emperor fell into illness, and neither medicine nor prayers had any effect.

A close associate remembered Minamoto no Yoshiie using an arrow to put a stop to the mystery case of some bird's cry, and he gave the order to a master of arrows, Minamoto no Yorimasa, to slay the monster.

One night, Yorimasa went out to slay the monster with his servant Ino Hayata (written as 猪早太 or 井早太 [10]), and an arrow made from an arrowhead he had inherited from his ancestor Minamoto no Yorimitsu and the tailfeathers of a mountain bird. An uncanny black smoke started to cover the Seiryō-den. Yorimasa shot his arrow into it, there was a shriek, and a nue fell down around the northern parts of Nijō Castle. Instantly Ino Hayata seized it and finished it off. [11] [12]

In the skies above the imperial court, two or three cries of the common cuckoo could be heard, and it is thus said that peace had returned. [11] After this, the emperor's health instantly recovered, [13] and Yorimasa was given the sword Shishiō as a reward.

The Nue's Remains

There are several accounts of what was done to the nue's corpse. According to some legends, like the Heike Monogatari, as the people in Kyoto were fearful of the curse of the nue, they put its corpse in a boat and floated it down the Kamo River. After the boat floated down the Yodo River and temporarily drifted upon the shore of Higashinari County, Osaka, it then floated into the sea and washed up on the shore between Ashiya River and Sumiyoshi River. It is said that the people in Ashiya courteously gave the corpse a burial service, and built a commemorating mound over its tomb, the Nuezuka. [11] The Settsu Meisho Zue states that "the Nuezuka is between Ashiya River and Sumiyoshi River." [11]

According to the Ashiwake bune, a geography book from the Edo period, a nue drifted down and washed ashore on the Yodo River, and when the villagers, fearful of a curse, notified the head priest of Boon-ji about it, it was courteously mourned over, buried, and had a mound built for it. [4] [8] It is further said that as the mound was torn down at the beginning of the Meiji period, the vengeful spirit of the nue started tormenting the people who lived nearby, and so the mound was hastily rebuilt. [12]

According to the Genpei Seisuiki and the Kandenjihitsu the nue was said to be buried at the Kiyomizu-dera in Kyoto Prefecture, and it is said that a curse resulted from digging it up in the Edo period. [4]

Another legend relates the spirit of the dead nue turning into a horse, which was raised by Yorimasa and named Kinoshita. As this horse was a good horse, it was stolen by Taira no Munemori, so Yorimasa raised an army against the Taira family. As this resulted in Yorimasa's ruin, it is said that the nue had taken its revenge in this way. [4]

Another legend says that the nue's corpse fell in the western part of Lake Hamana in Shizuoka Prefecture, and the legend of the names of places in Mikkabi of Kita-ku, Hamamatsu, such as Nueshiro, Dozaki ("torso"-zaki), Hanehira ("wing"-hira), and Ona ("tail"-na) come from the legend that the nue's head, torso, wings, and tail respectively fell in those locations. [14]

In Kumakōgen, Kamiukena District, Ehime Prefecture, there is the legend that the true identity of the nue is Yorimasa's mother. In the past, in the era when the Taira clan was at its peak, Yorimasa's mother lived in hiding in this place that was her home land, and at a pond called Azoga-ike within a mountains region, she prayed to the guardian dragon of the pond for her son's good fortune in battle and the revival of the Genji (Minamoto clan), and thus the mother's body turned into that of a nue due to this prayer and hatred against the Taira family, and then she flew towards Kyoto. The nue, who represented the mother, upon making the emperor ill, thus had her own son, Yorimasa, accomplish something triumphant by being slayed by him. The nue that was pierced by Yorimasa's arrow then came back to Azoga-ike and became the guardian of the pond, but lost her life due to wounds from the arrow. [15]: 337

Landmarks

- Nuezuka (Near Hashin Ashiya Station, at Matsuhama Park, Hyōgo Prefecture)

- The mound where the nue that floated down the river in the Heike Monogatari was buried. [11] The name of a nearby bridge, the Nuezuka-bashi originated from this Nuezuka. [13]

- Nuezuka ( Miyakojima-ku, Osaka)

- The mound where the nue that floated down Yado river in the Ashiwakebune was buried. The present mound was, as previously described, repaired in 1870 by Osaka Prefecture, and the small shrine was repaired in 1957 by the locals. [16]

- Nuezuka ( Kyoto Prefecture)

- Near the athletic field at Okazaki park. It is unknown how this is related to the legend of how the nue was buried at the Kiyomizu-deru in Kyoto. [4] [17]

- Nue pond ( Kyoto Prefecture)

- A pond at Nijō park, Chikara Town, Kamigyō-ku to the northwest of Nijō Castle. It is said that in this pond Yorimasa washed the blood-smeared arrow that went through the nue and killed it. [18] Presently, the remains of this pond has been remodeled into a water garden. [15]: 229–230 [19]

- Shinmei-jinja

- Shimogyō-ku, Kyoto. It is said that Yorimasa made a prayer here before killing the nue and subsequently donated the head of the lethal arrow as thanks. The arrowhead is kept as the treasure of the shrine. A photo is permanently exhibited, with the actual arrowhead shown to the public during an annual festival in September. [15]

- Yane-jizō

- Kameoka, Kyoto Prefecture. When Yorimasa prepared to kill the nue, he offered a prayer to his proctive god, Jizō Bodhisattva. Jizō promptly appeared in his dream and instructed him to make an arrow with the feathers of swans at Mt. Tori in Yada. Related to this legend, Jizō has the appearance of holding an arrowhead, but it is usually not exhibited to the public. [4] [13]

- Chōmyō-ji

- Nishiwaki, Hyōgo Prefecture. This land was originally the territory of Yorimasa. The temple features a statue of Yorimasa killing the nue. The nearby bamboo grove Ya-takeyabu (lit. "arrow bamboo grove") is said to be the place where Yorimasa picked the bamboo used for the lethal arrow. [15]

Other than these, in Beppu, Ōita Prefecture, it is said that there was a mummy of the nue in a theme park, the "Monster House (Kaibutsu-kan)" at the Hachiman Jigoku (one of the no-longer presently existing hot springs at the Hells of Beppu), and it was also said to be a precious treasure without parallel, but this theme park no longer presently exists, and the mummy's present whereabouts are unclear. [20]

References

- ^ 水木, しげる (1991). 日本妖怪大全. 講談社. pp. 324頁. ISBN 978-4-06-313210-6.

- ^ Cavallaro, Dani. (2010). Magic as Metaphor in Anime: A Critical Study. McFarland. p.88. ISBN 0-7864-4744-3. Google Books.

- ^ "Nue | Yokai.com". Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i 村上健司 (2007). 京都妖怪紀行 - 地図でめぐる不思議・伝説地案内. 角川oneテーマ21. 角川書店. pp. 12–17頁. ISBN 978-4-04-710108-1.

- ^ a b c 角川書店『角川漢和中辞典』「鵺」「鵼」

- ^ Rosen, Brenda. (2009). The Mythical Creatures Bible: The Definitive Guide to Legendary Beings. Sterling Pub. p. 107. ISBN 1-4027-6536-3. Google Books.

- ^ "鵺払い祭". 伊豆の国市役所. 2005. Archived from the original on 2012-04-15. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ a b "大阪市市政 大阪港紋章について". 大阪市役所. 2009-03-16. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ The Port of Osaka's Coat of Arms

- ^ 梶原正昭・山下宏明校注 (1991). 平家物語 上. 新日本古典文学大系. 岩波書店. pp. 256頁. ISBN 978-4-00-240044-0.

- ^ a b c d e 田辺眞人 (1998). 神戸の伝説. 神戸新聞総合出版センター. pp. 88–89頁. ISBN 978-4-87521-076-4.

- ^ a b 多田, 克己 (1990). 幻想世界の住人たち IV 日本編. Truth in fantasy. 新紀元社. pp. 319–323頁. ISBN 978-4-915146-44-2.

- ^ a b c 村上健司 (2002). 妖怪ウォーカー. Kwai books. 角川書店. pp. 64–76頁. ISBN 978-4-04-883760-6.

- ^ 村上健司 (2008). 日本妖怪散歩. 角川文庫. 角川書店. pp. 182–183頁. ISBN 978-4-04-391001-4.

- ^ a b c d 日本妖怪散歩.

- ^ "鵺塚". miyakojimaku.com. 2002. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ^ "鵺塚(京都)". kwai.org. 角川書店. Archived from the original on 2010-05-02. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ^ "KA068 鵺池碑". www2.city.kyoto.lg.jp. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ "上京区の史蹟百選/鵺池". 上京区役所総務課. 2008-10-21. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ 山口敏太郎・天野ミチヒロ (2007). 決定版! 本当にいる日本・世界の「未知生物」案内. 笠倉出版社. pp. 138–139頁. ISBN 978-4-7730-0364-2.