| Successor | Jefferson School of Social Science |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1923 |

| Dissolved | 1944 |

| Purpose | Educational, propagandist, indoctrinal |

| Headquarters | 28 E 14th Street, New York City |

| Coordinates | 40°44′7″N 73°59′32.5″W / 40.73528°N 73.992361°W |

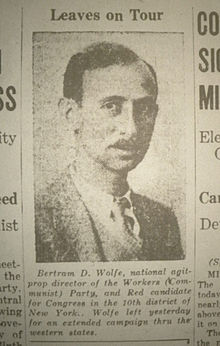

Director | Bertram Wolfe (1923–1929) |

Assistant Director | Ben Davidson (1923–1929) |

Director | Abraham Markoff (1929–1938) |

Director | Will Weinstone (1938–1944) |

| Advisory Board: David Saposs, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Floyd Dell, John Dos Passos | |

| Secessions | New Workers School |

| Affiliations | Communist Party USA |

The New York Workers School, colloquially known as "Workers School", was an ideological training center of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) established in New York City for adult education in October 1923. For more than two decades the facility played an important role in the teaching of party doctrine to the organization's functionaries, as well as offering a more general educational program to trade union activists.

The Workers School was a model for local CPUSA training centers in the area (e.g., the Jewish Workers University, founded in New York City in 1926) [1] and in other American cities (e.g., the Chicago Workers School). [2] It also provided the direct inspiration for the New Workers School, established by the breakaway Communist Party (Majority Group) headed by Jay Lovestone and Benjamin Gitlow (supported by Bertram D. Wolfe and Ben Davidson) after they left the Communist Party in 1929.

The Workers School was dissolved through merger in 1944, becoming part of the CPUSA's Jefferson School of Social Science.

History

Background

Over the course of the spring and summer of 1919, the Socialist Party of America divided into competing Socialist and Communist wings. [3] In the aftermath of this bitter split, the electorally-oriented Socialists retained control of a number of key public institutions of the party, including the Rand School of Social Science, a trade union and party training facility located in New York City. (Historian Marvin E. Gettleman [4] makes clear that the Workers School was seen by the Communists as the "historic successor" of the Socialists' Rand School.) [5]

The revolutionary socialist Communist wing, on the other hand, was rapidly driven underground by successive raids throughout late 1919 and early 1920 conducted at the behest of the Lusk Committee and the Justice Department. [6] With the country in the throes of the First Red Scare, the various organizations of the Communist movement eked out a furtive underground existence.

At the end of 1921 a decision was made by key party leaders, approved and driven ahead by the Communist International, for the Communist Party of America (CPA) to emerge from its underground existence of secret meetings and pseudonyms and to attempt to re-establish itself as a public organization known as the Workers Party of America (WPA). This effort was met with success, as a majority of the Finnish Socialist Federation, the Workers Council group, and others previously opposed to underground political activity flocked to the new organization. Membership soared from barely over 4,000 in the old underground CPA in 1922 to more than 15,000 in the legal WPA in 1923. [7]

The presence of such a large body of new members in the American Communist movement presented a challenge for the group of core cadres, as the understanding of party ideology by many of these new members was seen as defective. With the Rand School firmly in the grasp of the WPA's hated rivals, the need for a new party training school was seen as a pressing order of the day.

Establishment

By October 1923 a new Communist Party training school had been readied — the New York Workers School. [5] The facility was first located at 48–50 East 13th Street. [9] It moved to Communist headquarters at 28 East 14th Street on Union Square. In January 1934, the New Masses magazine advertised its address as 35 East 12th Street. [10] The facility moved yet again to a permanent home located at 35 East 12th Street — a building said by one FBI informant to be so "dingy, makeshift, and old" that it "should have been condemned". [5]

As with the rival Rand School of Social Science, the Workers School attempted to train trade union activists as well as key party cadres as part of what Gettleman has called "a systematic effort to mobilize learning to support the workers' side in the class struggle". [5] The teaching staff took pains to stress a close connection between learning and action, with a view to a hastening of the overthrow of capitalism. [5]

Dissolution

The Workers School was absorbed by the Jefferson School of Social Science in 1944 — a parallel Communist Party adult educational institution. [5] [9]

Organization

Curriculum

Each term at the school began with publication of an "Announcement of Classes". [5] The school launched in the fall of 1923 with a total of 12 courses as part of its curriculum, including Marxism, the history of international workers' movement, tactics of the Communist International, as well as " Biologic and Social Evolution." [5] In addition, courses in elementary and advanced English were offered for the benefit of the Communist movement's largely immigrant membership, as well as courses on "speech improvement" (the elimination of accents) and " platform speaking". [5]

Courses were conducted at night so that workers could remain on the job without interruption of their lives and financial loss. Workers School class announcements from the 1930s indicate that two successive class blocks ran each night, one running from 7:00 pm to 8:30 pm, followed by another group of classes meeting from 8:40 pm to 10:10 pm. [11] Classes were offered at the Workers School every weekday evening although most met only once or twice per week, with Tuesday being the night of the lightest course offerings. [11]

By 1927 the number of courses offered by the school had tripled, including courses on "Citizenship and Naturalization", labor journalism, and the creation and operation of shop newspapers, among others. [5] The school's "core course", entitled "Fundamentals of Communism", was taught in six different classes, including a day course for workers on the night shift. [5] By the middle 1930s, as many as 50 sections in this key course were offered at the Workers School and in satellite classrooms around New York City. [5]

The school occasionally published its own cheap editions of Marxist "classics" or issued its own textbooks, including one by leading Yiddish-language Communist Moissaye Olgin. [5]

Teaching method

By the time of its 15th anniversary in 1938, the Workers School had developed its own pedagogic method, forsaking the traditional academic format of lecture and recitation for a variation of the Socratic method in which short lectures were made with a view to posing of key questions for joint discussion by students. [12] This teaching method, borrowed from a small set of elite liberal arts colleges in the New England region, [13] was intended to shift the responsibility for learning to the students themselves. [12]

People

Joseph R. Brodsky had an as-yet-undefined affiliation with the school. [14]

Directors

- 1923–1929: Bertram D. Wolfe, assisted by Ben Davidson (politician) (better known by his "party name", D. Benjamin). [5] (Both of these taught at the Workers School in a full-time capacity, and both would leave the Communist Party with expelled leader Jay Lovestone in 1929, taking up work at the so-called New Workers School established by the rival Communist political organization which they helped found.)

- 1929–1939: Abraham Markoff, a New York pharmacist who died in 1938 [15]

- 1938–1944: Will Weinstone [15]

Advisory Council

Members of the advisory council [5] included:

- David Saposs: labor historian

- Elizabeth Gurley Flynn: former IWW organizer

- Floyd Dell: editor of The Masses

- John Dos Passos: left-wing novelist [5]

Teachers

Many prominent leftists taught there, including:

- Herbert Aptheker [5]

- Alexander Bittelman (on Tactics of the Third International) [15]

- Earl Browder (on the Chinese Revolution) [5]

- Arthur W. Calhoun (on American Labor history) [15]

- Whittaker Chambers (on "Workers Correspondence") [5]

- William Z. Foster (on trade union issues) [5]

- Sender Garlin (on "Workers Correspondence") [5]

- Benjamin Gitlow [5]

- Mike Gold (on proletarian writing) [15]

- Elizabeth Lawson [5]

- Ludwig Lore [5]

- William Mandel [2]

- Frank Meyer [2]

- Scott Nearing (on Economics and contemporary Europe) [5]

- Harvey O'Connor [15]

- Juliet Poyntz [5]

- Morris Schappes [16]

- Doxey A. Wilkerson [5]

Students

- David Jenkins (later director of the California Labor School [16]

- Murray Bookchin, communalist (1921—2006)

Tuition and participation

In the estimation of the leading academic expert on the New York Workers School, the institution was largely self-supporting, with student tuition providing funds for the payment of modest salaries to the part-time teaching staff. [5] The cost of a 12-week course meeting once a week at the time of the Workers School's launch in 1923 was $3.50. [5] This fee was raised to $4 in 1927, with twice-weekly classes in English-language instruction priced at $6 for the 12 week term. [5] Reduced fees were available to trade unions and various other fraternal organizations seeking to sponsor students on scholarship. [5]

A core teaching staff taught between 10 and 15 classes a week in exchange for a weekly salary of $12 — an amount which was insufficient to cover the costs of life in New York City. [5] Pressure was placed upon instructors to maintain enrollment in the school by conducting classes in a lively style as for both political and economic reasons high enrollment levels by the Workers School's administration. [5]

Admission to the New York Workers School was not limited to members of the Communist Party and its youth section, the Young Communist League, but also included non-party students. [15] Indeed, the Workers School was envisioned not only as a training center but as a means of recruiting talented and sympathetic individuals into the Communist Party. [15] Students at the school were mostly of working-class origin and were often immigrants to the United States. [15] Workers in shoe, garment, and jewelry manufacturing as well as the building trades were particularly well represented, as were students having jobs in restaurants and retail shops. [15]

Participation topped the 1,000 student mark in the fall of 1926. [5] Annual attendance at the peak of the CPUSA's educational effort was approximately 5,000 students. [17] Eventually the Workers School would open up satellite schools in the Bronx, Harlem, Brooklyn, and in several New Jersey industrial towns across from New York City on the other side of the Hudson River. [15]

The school launched its own magazine, The Student-Worker, in February 1927, with members of the Student Council serving as the editorial staff of the publication. [18] Content of the magazine's first issue included a contribution by Bertram D. Wolfe, Director of the Workers School, as well as material produced by students on the aims of the school, teaching methods, and the selection of course topics. [18]

In the fall of 1929 participation was estimated at "over 1200", of whom about 20 percent were enrolled in basic English classes and the rest taking courses in history, politics, or other party training courses. [19] This represented a new record enrollment for the institution. [20]

It was noted in October 1929 that the New York Workers School also maintained a Ruthenberg Library and reading room, which was open nightly from 6:30 until 9:30 pm. [19] A campus newspaper was also launched at that date, Workers' School Journal, which was to be run under student management and to publish contributions made by students at the school. [20]

Branch campuses

Branches opened in the New York City area: the Bronx, Harlem, Brooklyn, and towns in New Jersey. [15]

Although the bulk of the New York Workers School's operations were conducted at its main facility, small branch campuses were periodically added in order to improve accessibility. In the fall of 1929 the Communist Party operated a "Bronx Branch of the Workers' School", located at 2700 Bronx Park East. [19] A total of 60 students began the fall term at that location. [19]

Impact

In the late 1920s, the Workers School advocated for issues including the Sacco and Vanzetti trials, "Hands-Off-China" (for Shanghai Massacre), and "Passaic Relief" (for the Passaic Textile Strike). [15]

In 1949, FBI undercover agent/informer Angela Calomiris testified during the Foley Square trial that she took "educational courses" on communism at the Jefferson School of Social Service and the New York Workers School. [21] [22]

In the 1950s, the Workers School remained part of discussion of Communist infiltration in America. For example, in 1959, Frank Meyer, then anti-communist editor at National Review magazine, formerly a communist educator, testified to three phases of Communist training operations: 1) public agitation and propaganda, 2) molding of hard-core Communists, and 3) inner party training schools, the last of which, as he explains was:

... for the purpose of putting a final hardness, understanding from the party's point of view, toughness, on the Communist who is already approaching top leadership positions ...

The third type of training consists of a network of schools, full-time party schools, from the local level — section schools — through district schools, to national schools, and finally to the international schools that have been run over the years under various names by the international Communist movement. [23]

Legacy

In the estimation of one historian, for all its advocacy of political militance by the staff of the New York Workers School, the actual outcome was mild:

Anticommunist ideologues entertained lurid fantasies of party cadres stepping right out from a classroom discussion of one of Lenin's pamphlets and violently assaulting the U.S. Government. But, despite the rhetoric of direct action, and student-staff willingness to apply communist doctrines on the streets, on picket lines, or in union struggles, there is no evidence that would suggest that the Workers School, or any other party educational enterprise, was some U.S. equivalent of the Smolny Institute, the academy from which the Russian Bolsheviks made their successful armed seizure of state power in 1917." [5]

The New York Workers School was emulated by the Communist Party on a smaller scale in other key American industrial cities during the period of its greatest strength, the late 1930s and early 1940s. [24]

Former Soviet spy Whittaker Chambers mentioned the Workers School (which he called the "Workers Center") in his memoirs:

Behind Comrade Angelica sat Comrade Tom O'Flaherty. He was a big, unhappy Irishman, who lived sadly in the shadow of his celebrated brother, Liam, the author of The Informer and The Assassin. He drank heavily, and I have sometimes seen him lying, stiff and foul, in front of the Workers Center on Union Square. [25]

See also

- Rand School of Social Science (1906)

- Work People's College (1907)

- Brookwood Labor College (1921)

- New York Workers School (1923):

- New Workers School (1929)

- Jefferson School of Social Science (1944)

-

Highlander Research and Education Center (formerly Highlander Folk School) (1932)

- Southern Appalachian Labor School (since 1977)

-

San Francisco Workers' School (1934)

-

California Labor School (formerly

Tom Mooney Labor School) (1942)

- Seattle Labor School (1946–1949) [26]

-

California Labor School (formerly

Tom Mooney Labor School) (1942)

- Los Angeles People's Education Center [27]

- Continuing education

Footnotes

- ^ Michaels, Tony (2011), "The New York Workers School, 1923-1944: Communist Education in American Society", in Lederhendler, Eli (ed.), Communism and the Problem of Ethnicity in the 1920s, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 40, ISBN 9780199842353

- ^ a b c Hunt, Jonathan (2015). "Communists and the Classroom: Radicals in U.S. Education, 1930–1960". Composition Studies. 43 (2). Cincinnati, OH: University of Cincinnati: 22–45. Retrieved February 7, 2016.

- ^ The most accessible treatment of this sometimes confusing factional war remains Theodore Draper, The Roots of American Communism. New York: Viking Press, 1957.

- ^ "Marvin E. Gettleman papers". New York Public Library. Retrieved February 7, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai Gettleman, Marvin E. (1993). "The New York Workers School, 1923-1944: Communist Education in American Society". In Brown, Michael E.; Martin, Randy; Rosengarten, Frank; Snedeker, George (eds.). New Studies in the Politics and Culture of U.S. Communism (paperback ed.). New York: Monthly Review Press. pp. 261–280. ISBN 9780853458524.

- ^ See: Draper, The Roots of American Communism, passim.

- ^ Davenport, Tim, "The Communist Party of America (1919-1946): Membership Figures", Early American Marxism website, www.marxisthistory.org/

- ^ "Red Squad - A2001-074.120 : Samuel Dardeck". City of Portland Archives. August 6, 1941. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ^ a b Turner, Adrian (2001). "Guide to the New York Workers School Materials". Special Collections and Archives.

- ^ "New Masses". New Masses. January 2, 1934. p. 3. Retrieved March 14, 2017.

- ^ a b American Legion, Isms. Second Edition. Indianapolis, IN: American Legion, 1937. Reproduced in Gettleman, "The New York Workers School, 1923-1944", p. 269.

- ^ a b Richard H. Rovere, "School for Workers", The New Masses, vol. 29, no. 12 (December 13, 1938), p. 18.

- ^ These included Sarah Lawrence College, Bennington College, the New College at Columbia University, and some courses at Yale and Harvard. See: Rovere, "School for Workers", p. 18.

- ^ Hearings of the United States Congress House Committee on Un-American Activities. US GPO. 1950. p. 2979 (Lowenthal), 2988 (death), 2992. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Gettleman, Marvin E. (1990), "Workers School", in Buhle, Mari Jo; Buhle, Paul; Georgakas, Dan (eds.), Encyclopedia of the American Left, New York: Garland Publishing Co., pp. 853–854, ISBN 9780824037130

- ^ a b Jenkins, David (1993). "The Union Movement, the California Labor School, and San Francisco Politics, 1926-1988" (PDF). University of California, Berkeley. p. 31. Retrieved July 10, 2016.

- ^ Filardo, Peter, "Guide to the Jefferson School of Social Science (New York, N.Y.) Records and Indexes," Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University, New York City, 2009.

- ^ a b "Workers' School Students Have Magazine; Interesting Article in First Issue", Daily Worker, vol. 4, no. 35 (February 23, 1927), p. 4.

- ^ a b c d "1200 Attend Workers School", Daily Worker, vol. 6, no. 188 (October 14, 1929), p. 2.

- ^ a b "Workers School Starts Second Week Tonight", Daily Worker, vol. 6, no. 189 (October 15, 1929), p. 2.

- ^ Porter, Russell (April 27, 1949). "Communist Drive in Industry Bared: Girl Aide of FBI Testifies of 7 Years as Communist". The New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved April 2, 2017.

- ^ Porter, Russell (April 29, 1949). "Communist Drive in Industry Bared: Girl Aide of FBI Testifies Her Efforts on Waterfront Found Workers Cool". The New York Times. p. 11.

- ^ Meyer, Frank (July 21–22, 1959). "Communist Training Operations". Hearings Before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Washington, DC: U.S. House of Representatives (Eighty-Sixth Congress): 1007–1025, 1037, 1040–1041. Retrieved February 7, 2016.

- ^ Harvey Klehr, The Heyday of American Communism: The Depression Decade. New York: Basic Books, 1984; p. 372.

- ^ Chambers, Whittaker (1952). Witness. New York: Random House. pp. 222–223. LCCN 52005149.

- ^ Burnett, Lucy Marie. "Pacific Northwest Labor School: Educating Seattle's Labor Left". University of Washington. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ^ "Re: Workmen's Educational Association - San Francisco". July 26, 2000. Archived from the original on August 7, 2016. Retrieved February 7, 2016.

Further reading

- "Workers’ School in New York City Opens Second Term", Daily Worker [Chicago] vol. 1, whole no. 331 (February 5, 1924), p. 3.

- Gettleman, Marvin E. (1993). "The New York Workers School, 1923-1944: Communist Education in American Society". In Brown, Michael E.; Martin, Randy; Rosengarten, Frank; Snedeker, George (eds.). New Studies in the Politics and Culture of U.S. Communism (paperback ed.). New York: Monthly Review Press. pp. 261–280. ISBN 9780853458524.

- Gettleman, Marvin E. (1990), "Workers School", in Buhle, Mari Jo; Buhle, Paul; Georgakas, Dan (eds.), Encyclopedia of the American Left, New York: Garland Publishing Co., pp. 853–854

External links

- Peter Filardo, "Guide to the Jefferson School of Social Science (New York, N.Y.) Records and Indexes," Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University, New York City, 2009.

- Turner, Adrian (2001). "Guide to the New York Workers School Materials". Special Collections and Archives.

- Meyer, Frank (July 21–22, 1959). "Communist Training Operations". Hearings Before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Washington, DC: U.S. House of Representatives (Eighty-Sixth Congress): 1007–1025, 1037, 1040–1041. Retrieved February 7, 2016.