The Merced Assembly Center, located in Merced, California, was one of sixteen temporary assembly centers hastily constructed in the wake of Executive Order 9066 to incarcerate those of Japanese ancestry beginning in the spring of 1942, following the attack on Pearl Harbor and prior to the construction of more permanent concentration camps to house those forcibly removed from the West Coast. [1] The Merced Assembly Center was located at the Merced County Fairgrounds and operated for 133 days, from May 6, 1942 to September 15, 1942, with a peak population of 4,508. [2] 4,669 Japanese Americans were ultimately incarcerated at the Merced Assembly Center. [3]

Establishment of Merced Assembly Center

Political Climate and Executive Order 9066

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, anti-Asian prejudice rapidly began spreading through the West Coast, mainly affecting the state of California. This prejudice was not new, for it began spreading after Chinese immigration increased during the Gold Rush. At the time, Chinese people began working and began to be perceived as competition by White working-men. Once Japanese people began to immigrate, people started to put up anti-Asian propaganda. White-owned establishments had signs that stated that service would not be given to people of Asian descent. When the attack on Pearl Harbor occurred, most people were in shock, but Japanese-Americans had a feeling it would occur. In actuality, Japanese Americans began to be threatened about being placed in camps beginning in 1937. [4] After the Alien Registration Act of 1940, the FBI made a list of potentially dangerous immigrants who were German, Italian, or Japanese. [4] In November 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt received a secret letter from Curtis B. Munson, which stated that many Japanese-Americans were loyal to the United States, but the West Coast was vulnerable because some Japanese-Americans were still loyal to Japan. [4] After the attack on Pearl Harbor, those considered dangerous by the FBI were arrested. The accounts that they had in American banks that were traced back to Japanese branches were frozen. [4] The attack on Pearl Harbor caused many American citizens to feel afraid and anti-Asian prejudice increased. Therefore, communities began to grow afraid of those of Japanese descent. There were many reports of Asian Americans being harassed by others. Once Executive Order 9066 was issued, some Japanese-Americans fled to Mexico to escape detention camps. [5] The Mexican government did not surrender any of their Japanese-American refugees to the United States. [5]

Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, fear spread regarding national security. In the state of California, the major worry was along the West Coast. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Executive Order 9066. It ordered the immediate forced removal and detention of Japanese Americans, even though they were not directly mentioned within the executive order. [6] As a result of Executive Order 9066, more than 110,000 Japanese Americans were forced to relocate to temporary "assembly centers" primarily located within the Central Valley. [7] A month after Executive Order 9066 was enacted, Public Law 503 was enacted, it allowed federal courts to enforce the orders from Executive Order 9066. Many Japanese Americans were not aware they would be confined, in some cases, for almost four years. The evacuees were not allowed to take a lot of their belongings with them, with only one duffel bag and two suitcases leaving the rest to be sold or stored. Due to everything happening so fast, everything was being sold at unfair prices and people were taking advantage of any items that the Japanese Americans were leaving behind. [8]

Location of the Assembly Centers

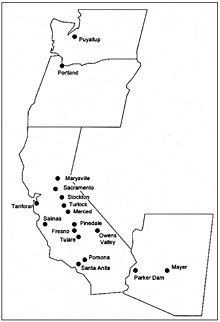

The first phase entailed taking residents from their houses and putting them in military-controlled detention facilities nearby. After Japanese Americans started reporting to collection points near their homes, they were relocated to assembly centers. With a total of seventeen centers, many of them were in California but some were in Arizona, Washington, and Oregon. The locations of these centers in California were: Fresno, Owens Valley, Marysville, Merced, Pinedale, Pomona, Sacramento, Salinas, Santa Anita, Stockton, Tanforan, Tulare, and Turlock. The centers in Arizona were located at Mayer and Parker Darn. One of the centers was in Portland, Oregon. The final center was in Puyallup, Washington.

The largest assembly center was in Santa Anita. Eleven of the assembly centers were at racetracks and fairgrounds. [9] The others were: unsuitable facilities, migrant workers camps, abandoned corps, and a former mill site. The owners of eleven racetracks and fairgrounds signed leases with the government. The mess halls of the centers became potential breeding sites for epidemic outbreaks, compounding the health dangers of the unsanitary living quarters. All of them were staffed by inexperienced personnel who lacked basic hygiene and food-handling skills. The army was aware and concerned with the assembly centers: “Assembly Centers are not and cannot, without the expenditure of tremendous sums of money for space and facilities in duplication of those which will be provided on relocation sites, be designed to permit the development and maintenance of a vocational, educational, recreational and social program. Long residence in an assembly center is bound to have a demoralizing effect” (52). [10]

Forced Relocation to Merced

The Western Defense Command put out 108 Civilian Exclusion Orders to forcibly relocate people of Japanese ancestry who lived on the West Coast. The purpose in doing this was to transfer them to temporary detention centers. Those closest to army areas were evacuated first and an effort was put in to send them to camps close to their homes. The first order went out on March 24, 1942 for 55 families closest to the attack on Pearl Harbor, who would eventually be sent to Manzanar and Minidoka internment camps. [11] Those forcibly relocated to Merced came from mostly rural farming communities, including 1,600 people from Colusa County and Yolo County. Around 1,400 came from nearby regions of Modesto, Merced, and Turlock. 1,000 more came from northern coastal towns. [12] Many owned land and while most were forced to sell or lost their property, but evacuees from Cortez, Cressey, and Livingston were part of collective farming organizations that ensured that they could keep their farms and homes. [13]

Amidst this chaotic process, civilians experienced anxiousness and excitement at the same time. The main order they had to follow was in regards to what they were allowed to bring, amongst vaccination and tag requirements. Families were only allowed to have what they could carry. They were required to have: bedding and linens, toiletries, clothing, dining utensils, and necessary personal hygiene products. Prior to being evacuated, civilians had to get their affairs in order, such as owned and rented properties. Due to the unknown duration of time of being away, most people lost leases and had to get rid of their homes and businesses. Few had the opportunity to store their belongings safely for recovery post liberation. [14]

Dorothea Lange's Censored Images

This forced relocation process was documented by Dorothea Lange, an American photographer hired by the government to show how well the Japanese internees were being treated in the camps. While she was hired to do this job, 97% of her images were censored by the government and not seen until many years later. The existence of the images to the public today is mainly due to their transmission into the National Archives and their presence in the traveling exhibition, Executive Order 9066, by Richard Conrad, Lange’s assistant, and his wife. In order to justify the perception that the government wanted to show, Lange was told not to make sure barbed wire, watchtowers, and armed soldiers were not depicted in any of the images. To enforce this, she was constantly tracked and followed by members of the WRA. In addition, she was always trying to be caught in breeches of agreement by U.S Army Major Beasley who was never successful.

Lange did not agree with the internment of Japanese people. By taking on this job, she hoped to show the truth of what these civilians were going through, which could ultimately help them. Despite her beliefs, captions of the images aligned with government language. [15] It is believed that she did this to satisfy the federal government and the idea that this event in history was to protect Japanese civilians. She thought that the words would be censored as were her images. During this time, another photographer, Ansel Adams, was taking photographs of the Manzanar Internment Camp under his own direction. While Lange’s images were being censored, she urged him to release the truth through his photographs and create change. Adams declined to do this and only showed a “make the best of it” approach through his project. [16]

Her images challenged the ideas that were being pushed that the Japanese were traitors. She showed their common experience through her specialty, portraits, as well as through landscape and close up shots, like of piles of luggage. [17]

Gallery of Lange's Images

Assembly Center Conditions & Facilities

Security

Security at the detention center was not unlike a prison. As Bob Fuchigami, who was incarcerated at the Merced Assembly Center as a child, remembers, "Merced was like a prison camp, surrounded by barbed wire, guard towers manned by military. I'm sure they had rifles and machine guns or whatever. And they had jeep patrol coming around the perimeter of the camp and they would come fairly often. At night the search lights were there and criss-crossed the camp....We were told, you go beyond that fence you're going to get shot." [18] A twice-daily roll call was held, in the mornings and evenings. One civilian policeman was assigned for every two hundred inmates. The police were authorized to enter and search any and all facilities in the detention center without a warrant. The police also screened all visitors and incoming luggage and parcels for contraband, though mail remained protected from surveillance and censorship. [19]

Medical

Medical facilities included doctor’s offices, hospital wards, a pharmacy, a dental clinic, and a dietician's unit. The dental clinic used a homemade dental chair made out of a barber chair. [20] In a 1942 letter from Mr. Henry Fujita to his boss, Mr. H.A. Strong of Electrolux Corporation, he writes that “there has been a number of unnecessary deaths” due to lack of medical resources and attention. He goes on to describe an incident on July 13, 1942, where he went to see the camp doctor because his children fell seriously ill and the doctor brushed it off as a common cold. Fujita’s letter further details the kind of conditions that Japanese Americans were forced to endure during this time period that may have contributed to the 10 deaths that occurred at the detention center. [21]

Housing and Barracks

Since the government did not have the resources at the time to incarcerate 110,000 people adequately, most of the assembly centers were repurposed from existing race tracks or fairgrounds, including at Merced. Cattle stalls on racetracks were cleared out and made to fit families of six. Since the Merced Assembly Center had to be built in a very short amount of time, facilities were often built poorly out of crude materials and were not able to withstand rain and wind. Floods would often occur as well as insects invading housing due to the doors not being screened and properly built. [22] The living areas were extremely crowded which contributed to a lack of privacy. As Marion Michiko Bernardo, who was incarcerated at the Merced Assembly Center as a young girl, remembers, "The rooftops were at this angle and there was no ceiling in between the whole building. People could hear me crying and everything. I remember that." [23] Buildings included housing, laundry facilities, communal restrooms, and mess halls. There was very little space available for recreation.

Sanitation

Sanitation in the detention center was poor. The barracks were poorly constructed, with no indoor plumbing and inadequate communal bathrooms and showers that lacked partitions. Ruth Ihara, who was incarcerated at the Merced Assembly Center, described the conditions she encountered in a letter: "When we first saw our living quarters we were so sick we couldn't, eat, walk, or talk. We couldn't even cry till later." She continued, "... but gee—you should see the —er—latrines. There is absolutely no privacy or sanitation—10 seats lined up (hard, fresh-sawed, un-sandpapered wood) and it flushes automatically about every 15 minutes." [24]

Food

The barracks did not have kitchens and meals were served in a central mess hall, staffed by Japanese American cooks incarcerated at the detention center. The food was of poor quality, unfamiliar and unappetizing to Japanese Americans, and the cooks struggled to prepare edible meals. [25] Some of the incarcerated established their own victory gardens around the barracks. [25]

Climate

Because the detention center operated from the late spring through the early fall in a region that routinely experiences triple-digit temperatures, those incarcerated at Merced had to cope with extreme heat. [12] As Harry Fujita, who was incarcerated at Merced, wrote in a letter at the time, "In the prevailing hot weather our rooms are just like ovens. There is no escape because there isn't any artificial or natural shade except for a few scattered trees in inconvenient places." [21]

Life at Merced Assembly Center

Government

Like the other temporary detention centers, the Merced Assembly Center was administered by the Wartime Civil Control Administration. [26] There were limited efforts at self-government, with both appointed and elected representatives to advise camp authorities. However, the WCCA prohibited Issei from participating and eventually abolished these advisory committees altogether. [27] Other platforms for residents of the Merced Assembly Center still remained. These included sending in concerns to the Mercedian or verbally participating in forums held in the center’s town hall.

The Mercedian Newspaper

Like the other assembly centers, the Merced Assembly Center printed its own newspaper to inform people of current events taking place in the camp. The Mercedian published two issues per week between June 9, 1942 and August 29, 1942. [28] Articles were written by incarcerated Japanese Americans, though the Mercedian, like other assembly center newsletters, was only written in English and subject to surveillance and censorship by the WCCA. [29] [30] Mercedian staff included managing editor Oski Taniwaki and editor Tsugime Akaki. [31] Taniwaki had previously been the English language editor of Shin Sekai, a popular Japanese language newspaper based in San Francisco. [32]

Evidence of Censorship

Censorship in both the WCCA and WRA-administered concentration camps was deeply rooted, as these camps never intended for there to be “free speech” critiquing the government, which kept these newspapers running. [33] Presence of censorship was oftentimes blatant as in the example of the WCCA camps, which had an internal document titled "Report of Operations" which describes the basic procedures of censorship. One of the highlights of the “Report of Operations” was that every copy of the assembly center newsletter had to be edited and approved by the Public Relations representative which was then handed to the center manager. [34]

Education / Schooling

Non-compulsory education programs were offered to elementary, middle, and high school students, along with some adult classes. There were twenty teachers at the assembly center, all of them Japanese American volunteers. Classes ran from June 10, 1942 to August 21, 1942, enrolling roughly 330 elementary students, 450 middle and high school students, and 100 adults. Elementary subjects included arithmetic, reading, spelling, choir, dancing, story-telling, drawing, and crafts. High school subjects included English, Algebra, Geometry, Trigonometry, Gen.Science, Chemistry, American History, Government, Bookkeeping, and Business Training. Adult classes offered English instruction to incarcerated Issei, along with assorted other subjects. The school lacked adequate space and supplies, with some classes held in grandstands and empty barracks with students sitting on the floor for lack of desks. The detention center also held a ceremony for students who missed their high school graduation due to their forced relocation. [35] [36]

Employments / Jobs

To keep operating costs low, the WCCA employed the incarcerated in the everyday work of running the assembly centers. [37] Employment was voluntary and, depending on their classification, they were paid $8 for unskilled work, $12 for skilled work, and $16 for professional work, far below the prevailing wage for American GIs. [13] Beginning in June 1942, the WCCA also provided the incarcerated with monthly allowances to purchase basic necessities such as food, hygiene items, and clothing. [38] Men and women incarcerated at the Merced Assembly Center were employed throughout the detention center, including in the improvement of the hastily constructed facilities and even as an internal police unit known as the "Green Peas." [13]

Family Life

There were a total of 21 births and 10 deaths at the Merced Assembly Center. The first birth at the detention center was a girl born to Mrs. Haruko Agatsuma. [12] There were a total of four weddings administered at Merced Assembly Center. Under the watch of a security guard, the couples were permitted to go to Merced in order to apply for a marriage license, find a wedding dress, and have a wedding picture captured. The weddings were held at Merced Fairground Exhibit Hall with a guest limit of 200. Families at Merced Assembly Center shared a lot of their time together since most were crammed into one small room. There was very little privacy between families as the room partitions did not extend from the floor to the ceilings. It was said that greetings, cries, and screams could be heard from one room to the next. [39]

Recreation

Life was made more tolerable at the Merced Assembly Center through recreation. [40] There were various competitions, including kite flying contests and talent shows. [41] Music appreciation hour was also held to give the incarcerated some relief off of the daily stress of their new lives. [41] Surprisingly, school was not mandatory for students. [40] Many kids, especially the older ones, took advantage of the opportunity to use their time for recreational activities. [40] Many found this time to be more fun and fulfilling. [40] Recreational activities were centered around baseball and sumo wrestling. [42] Other commonly known sports were played as well, including basketball, badminton, football, and ping pong. [42] Other activities consisted of boy scouts, girl scouts, dances, and craft shows. [42] The first month, however, had minimal recreation due to limited space for activities and facilities. [42] Originally, activities were only held on the inside of a racetrack field. [42] Camp management was able to expand the barbed wire fence to the outside of the racetrack and bleachers. Everyone was excited to utilize the extra space for entertainment. [42]

Closure

Relocation to Amache (Colorado)

An advanced group of 212 Japanese Americans were transferred from the Merced Assembly Center on August 25 to help set up a more permanent concentration camp located in Amache, Colorado, also known as the Granada War Relocation Center. Amache was much more spacious, containing about 8000 acres of land for irrigation and having facilities big enough to house about 6,500 to 7,000 evacuees. [43] Initially, authorities planned to send groups of 500 from Merced to Amache daily, but they soon realized that they would need more time because the camp was not ready to hold that many people. [44] The pace slowed to a group of roughly 500 every other day, then they took a 5 day break and sent the last three groups out, with the last group being transferred on September 15, 1942. In addition to those from Merced, 2,000 evacuees from other assembly centers were also relocated to Amache. [43] By the time the Amache concentration camp closed in 1945, 10,000 people had been incarcerated in the camp. [45]

Preservation & Remembrance

California Historical Landmark

A historical marker was placed in 1982 to honor the history behind the assembly centers. [46] This marker, located at the former location at the Merced County Fairgrounds, is marker number 934, one of ten historical markers that are placed to honor other temporary detention centers and those who were forcibly removed to these centers. [47]

Merced Assembly Center Memorial

The Merced Assembly Center Memorial is located at the Merced County Fairgrounds. The 2008 Fair Board was hesitant to place the Memorial, but once the space was granted, there was fundraising which led to the Memorial being open to the public in 2010. [48] The memorial consists of the names of those incarcerated at the assembly center, along with a statue of families waiting with their luggage in front of the wall and a reflection pool behind it. There are several additional plaques with more information about the Merced Assembly Center and what the memorial represents.

See also

- Anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States

- Internment of Japanese Americans

- Executive Order 9066

- Amache National Historic Site

External links

- WWII Japanese American Assembly Center newsletters, UC Merced Library and Special Collections

- The Merced Assembly Center Documentary Interviews, UC Merced Library and Special Collections

- The Merced Assembly Center: Injustice Immortalized, Valley PBS

Further reading

- Gordon, L. & Okihiro, G.Y. (Eds.). (2008). Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment. W.W. Norton & Company.

- Matsumoto, V.J. (1993). Farming the Home Place: A Japanese Community in California,1919-1982. Cornell University Press.

References

- ^ "Sites of incarceration | Densho Encyclopedia". encyclopedia.densho.org. Retrieved 2022-07-11.

- ^ "Merced (detention facility) | Densho Encyclopedia". encyclopedia.densho.org. Retrieved 2022-07-11.

- ^ Matsumoto, Valerie J. Farming the Home Place : A Japanese Community in California, 1919-1982. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-5017-1191-6. OCLC 1130275772.

- ^ a b c d "National Park Service: Confinement and Ethnicity (Chapter 3)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ^ a b "Japanese Mexican removal | Densho Encyclopedia". encyclopedia.densho.org. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ^ "Executive Order 9066 | Densho Encyclopedia". encyclopedia.densho.org. Retrieved 2022-04-25.

- ^ "Executive Order 9066: Resulting in Japanese-American Incarceration (1942)". National Archives. 2021-09-22. Retrieved 2022-04-25.

- ^ "A Guide to the War in the Pacific: The First Year". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ^ "National Park Service: Confinement and Ethnicity (Chapter 3)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ^ Fiset, Louis (1999). "Public Health in World War II Assembly Centers for Japanese Americans". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 73 (4): 565–584. doi: 10.1353/bhm.1999.0162. ISSN 1086-3176. PMID 10615766. S2CID 30044369.

- ^ "Assembly Centers: Roundup".

- ^ a b c "Merced (detention facility) | Densho Encyclopedia". encyclopedia.densho.org. Retrieved 2022-04-25.

- ^ a b c Matsumoto, Valerie J. (1993). Farming the Home Place : A Japanese Community in California, 1919-1982. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. pp. 106–107. ISBN 978-1-5017-1191-6. OCLC 1130275772.

- ^ Matsumoto, Valerie. Farming The Home Place. Cornell University Press. pp. 87–118.

- ^ "Lange Photographs Japanese American Incarceration".

- ^ Lange, Dorothea (February 17, 2008). Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the censored images of Japanese American internment. W. W. Norton & Company.

- ^ "How One Woman Shaped the Collective Memory of Japanese American Removal".

- ^ "Bob Fuchigami remembers thinking about sneaking u… (en-denshovh-fbob-01-0015-1) | Primary Sources | Densho Encyclopedia". encyclopedia.densho.org. Retrieved 2022-07-11.

- ^ "Assembly centers | Densho Encyclopedia". encyclopedia.densho.org. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ^ "Merced (detention facility) | Densho Encyclopedia". encyclopedia.densho.org. Retrieved 2022-04-25.

- ^ a b Fujita, Henry Katsumi (1942-08-09), Letter from Henry [Katsumi] Fujita to Mr. H. A. Strong, Electrolux Corporation, August 9, 1942, retrieved 2022-04-25

- ^ "Merced (detention facility) | Densho Encyclopedia". encyclopedia.densho.org. Retrieved 2022-05-08.

- ^ "Marion Michiko Bernardo talks about having a diff… (en-denshovh-bmarion-01-0011-1) | Primary Sources | Densho Encyclopedia". encyclopedia.densho.org. Retrieved 2022-07-11.

- ^ "Merced (detention facility) | Densho Encyclopedia". encyclopedia.densho.org. Retrieved 2022-07-12.

- ^ a b Matsumoto, Valerie J. Farming the Home Place. Valerie J. Matsumoto. p. 106. ISBN 9781501711923. OCLC 1139484870.

- ^ "Wartime Civil Control Administration | Densho Encyclopedia". encyclopedia.densho.org. Retrieved 2022-07-11.

- ^ "Assembly centers | Densho Encyclopedia". encyclopedia.densho.org. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ "Merced (detention facility) | Densho Encyclopedia". encyclopedia.densho.org. Retrieved 2022-07-12.

- ^ "Assembly centers | Densho Encyclopedia". encyclopedia.densho.org. Retrieved 2022-07-12.

- ^ Mizuno, Takeya (2003-10-01). "Journalism Under Military Guards and Searchlights: Newspaper Censorship at Japanese American Assembly Camps during World War II". Journalism History. 29 (3): 98–106. doi: 10.1080/00947679.2003.12062627. ISSN 0094-7679. S2CID 141262573.

- ^ "Merced (detention facility) | Densho Encyclopedia". encyclopedia.densho.org. Retrieved 2022-07-12.

- ^ "Shin Sekai (newspaper) | Densho Encyclopedia". encyclopedia.densho.org. Retrieved 2022-07-12.

- ^ "Newspapers in camp | Densho Encyclopedia". encyclopedia.densho.org. Retrieved 2022-12-07.

- ^ "Newspapers in camp | Densho Encyclopedia". encyclopedia.densho.org. Retrieved 2022-12-07.

- ^ "Merced (detention facility) | Densho Encyclopedia". encyclopedia.densho.org. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ^ History of Merced Assembly Center Schools, retrieved 2022-04-27

- ^ "Assembly centers | Densho Encyclopedia". encyclopedia.densho.org. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ "Assembly centers | Densho Encyclopedia". encyclopedia.densho.org. Retrieved 2022-07-12.

- ^ Matsumoto, Valerie (2019). Farming the Home Place. Cornell University Press. pp. 87–118. ISBN 9781501711923.

- ^ a b c d Viewcontent.cgi

- ^ a b at Merced Assembly Center, Writers (August 4, 1942). ""The Mercedian, Vol. 1 No. 15"". The Mercedian. p. 1. Retrieved May 2, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Merced_(detention_facility)

- ^ a b "Souvenir Edition". The Mercedian. August 29, 1942. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

- ^ "Merced (detention facility) | Densho Encyclopedia". encyclopedia.densho.org. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ^ "Granada Relocation Center, CO (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2022-05-02.

- ^ "Merced Assembly Center Historical Marker". www.hmdb.org. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ^ "Related Historical Markers". www.hmdb.org. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ^ "Merced's Japan Internment Memorial now 10 Years Old". Merced County Events. Retrieved 2022-04-27.