The Irish slaves myth is a fringe pseudohistorical narrative that conflates the penal transportation and indentured servitude of Irish people during the 17th and 18th centuries, with the hereditary chattel slavery experienced by the forebears of the African diaspora. Some white nationalists, and others who want to minimize the effects of hereditary chattel slavery on Africans and their descendants, have used this false equivalence to deny racism against African Americans [1] or claim that African Americans are too vocal in seeking justice for historical grievances. [2] It also can hide the facts around Irish involvement in the transatlantic slave trade. [3] The myth has been in circulation since at least the 1990s and has been disseminated in online memes and social media debates. [4] According to historians Jerome S. Handler and Matthew C. Reilly, "it is misleading, if not erroneous, to apply the term 'slave' to Irish and other indentured servants in early Barbados". [5] In 2016, academics and Irish historians wrote to condemn the myth. [6]

Common elements

Common elements to memes that propagate the myth are: [4] [6] [7]

- The conspiracy theory that historians and the media are covering up Irish slavery. [4]

- That all Irish people were enslaved after the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland in 1649. [4]

- Irish slaves were treated worse than African slaves. [4]

- Irish women were forced to reproduce with African men. [4]

- Intending to diminish the discrimination that African-Americans have historically experienced, with memes like "The Irish were slaves, too. We got over it, so why can't you?". [4]

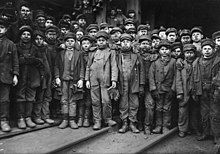

- Using photographs of victims of the Holocaust or 20th century child laborers, claiming that they are Irish slaves. [4]

- A reference to an alleged 1625 declaration by King James II to send thousands of Irish prisoners to the West Indies as slaves. James II had not been even born yet; he was born in 1633 and started his rule in 1685. 1625 saw the end of King James I's rule and the ascension of King Charles I to the throne. [4]

- The substitution of the victims of actual atrocities committed against enslaved Africans with Irish victims. [4]

Background

During British rule in Ireland, and particularly during the Plantations of Ireland and the Cromwellian conquest, the terms "slaves" or "bond slaves" were used to describe the "time-bound" system of servitude of tens of thousands of Irish. [8] [9] The official British legal terminology used was "indentured servants" whether the servants in question had willingly signed the indenture contract to emigrate to the Americas or were forced to go. [9] [1] In any other form, those transported unwillingly were not considered to be indentured. This included political prisoners, vagrants, convicts, prostitutes, [10] or people who had been defined as "undesirable" by the British government. Penal transportation of Irish people was at its height during the 17th century, most was for various felonies such as highway robbery, vagrancy (homelessness), burglary, and horse theft. Penal transportation was a general practice in Great Britain as well as Ireland. These were the offences most often punished with transportation for men in the 1670s, though for women it was theft. [11] They were then subjected to forced labour for a given period when they arrived in the Americas or Australia. [12] [5] [13] During this same period, the Atlantic slave trade was transporting millions of Africans across the Atlantic and bringing them to various European colonies in America (including British America) where they were purchased by European colonists and put to work.

Treatment of Irish indentured servants varied widely, but the transport, physical work, and living conditions have been compared by scholars to the treatment of enslaved Africans. [8] However, the usual period of indenture for an Irish person was from four years to nine years, after which they were free – able to travel freely, own property, and accumulate wealth. Additionally, the formerly indentured Irish person could now marry whom they chose and their children were born free. [8] Unlike Irish indentured servants, enslaved Africans generally were made slaves for life and this perpetual slave status was imposed on their children at birth. [4] [2] Both systematically and legally, enslaved Africans were subjected to a lifelong, inheritable condition of slavery that indentured Irish people never were. [8] Donald Harman Akenson makes the point that in this "white indentured servitude was so very different from black slavery as to be from another galaxy of human experience". [14] Additionally, in terms of numbers, the "most likely exaggerated" high estimates of Irish laborers sent to the Caribbean, along with estimates of total numbers of prisoners and indentured servants in British America, "pales by comparison" to the millions of enslaved Africans who were transported to the Americas." [15]: 56–7 [16]

Irish involvement in the slave trade

According to historian Nini Rodgers, in the 18th century "every group in Ireland [Gaelic, Hiberno-Norman or Anglo-Irish] produced merchants who benefited from the slave trade and the expanding slave colonies." [17] [14] During this same period, the transatlantic slave trade was transporting millions of Africans across the Atlantic and bringing them to various European colonies in the Americas, where they were purchased by European colonists and put to work. Although the Navigation Acts prevented Ireland from participating directly in the slave trade, Irish merchants of different religious and social backgrounds generated significant wealth by exporting goods to overseas plantations and importing slave-produced goods into Ireland as part of the triangular trade. [18] Exports of salted and pickled provisions to slave-colonies were central to economic expansion in Georgian era Cork, Limerick, and Belfast, while imports of West Indian sugar contributed to urban growth and the rise of a Catholic middle class. Rodgers concluded that by the end of the 18th century "Ireland was very much a part of the Black Atlantic World". [19]

Some Irishmen worked as "agents of empire". [20] Jane Ohlmeyer notes that by 1660, Irishmen, both Protestants and Catholics, "were to be found in the French Caribbean, the Portuguese and later Dutch Amazon, Spanish Mexico, and the English colonies in the Atlantic where they... forged commercial networks as they traded calicos, spices, tobacco, sugar, and slaves." [20] The French port of Nantes, in particular, was dominated by a community of exiled Irish Jacobites, and rose to prominence in the 18th century as France's foremost slave trading port. [21]

Irish Catholics made up more than two-thirds of the Anglo-Caribbean island of Montserrat's plantation owners as early as the 17th century, and according to historian Donald Akenson "they knew how to be hard and efficient slave masters." [22]

American historian Brian Kelly cautions against indicting "the country as a whole" as "overwhelmingly the benefits of Ireland’s involvement in transatlantic slavery went to the same class that presided over the misery that culminated in the horrors of famine and mass starvation." [23] [24] [25]

Origins and propagation

According to historian Liam Kennedy, the idea of 'Irish slavery' was popular within the nineteenth-century Irish independence movement Young Ireland. Young Irelander John Mitchel was particularly vocal in his claim that the Irish had been enslaved, although he was a supporter of the Atlantic slave trade in Africans. [26]

An Irish Times article notes that Irish republicans "are intent on drawing direct parallels between the experiences of black people under slavery and of Irish people under British rule", which has in turn been repurposed "by white supremacist groups in the US to attack and denigrate the African-American experience of slavery." [3] According to history professor Ciaran O’Neill of Trinity College Dublin, while those most active in propagating myth – who are often located in Australia and the United States – "want to create false equivalence between the Atlantic slave trade and the phenomenon of indentured Irish labour in the Caribbean" for the purpose of undermining the Black Lives Matter movement, [27] research librarian and independent scholar Liam Hogan "also makes the point that this narrative has been used to help obscure the fact that many Irish people participated in and profited from slavery." [28]

In the Dublin Review of Books, professor Bryan Fanning states: "The popularity of the 'Irish slaves' meme cannot simply be blamed on the online propaganda of white supremacist groups. There are several elements at play beyond the deliberate falsification of the past. Widespread acceptance online of a false equivalence between chattel slavery and the treatment of Irish migrants appears to be rooted in Irish narratives of victimhood that continue to be articulated within Ireland’s cultural and political mainstreams." [1] Irish people's history has embraced both a legacy of identification with the oppressed, and elements of racism in the service of Irish nationalism, according to Fanning. [1]

In print

A number of books have been written on the subject, including White Cargo: The Forgotten History of Britain's White Slaves in America; and The Irish Slaves: Slavery, Indenture and Contract Labor Among Irish Immigrants. According to Hogan, the most influential book to assert the myth was They Were White and They Were Slaves: The Untold History of the Enslavement of Whites in Early America, self-published in the US in 1993 by conspiracy theorist and Holocaust denier [29] Michael A. Hoffman II (who blamed Jews for the Atlantic slave trade). [30]

To Hell Or Barbados: The Ethnic Cleansing of Ireland (2000), by Irish writer Sean O'Callaghan, is advertised as "a vivid account of the Irish slave trade: the previously untold story of over 50,000 Irish men, women and children who were transported to Barbados and Virginia." [31] [4] [32] The book continued the same themes as Hoffman, and introduced the concept of Irish women being forcibly bred with Africans. [33] Other authors repeated these lurid descriptions of Irish women being compelled to have sex with African men. [34] [35] The book has been described as shoddily researched. [4] Brian Kelly calls the book "highly problematic" and writes: "The careless blurring of the lines between slavery and indenture in O’Callaghan’s work, rooted in sentimental nationalism than a commitment to white supremacy – provided an aura of credibility for the ‘Irish slaves’ meme that it would not have otherwise enjoyed." [36] According to The New York Times, "In America, [O'Callaghan's] book connected the white slave narrative to an influential ethnic group [ Irish-Americans] of over 34 million people, many of whom had been raised on stories of Irish rebellion against Britain and tales of anti-Irish bias in America at the turn of the 20th century. From there, it took off." [4]

Online

O'Callaghan's claims were repeated on Irish genealogy websites, the Canadian conspiracy theory website GlobalResearch.ca, and Niall O'Dowd's IrishCentral. The 2008 article on GlobalResearch.ca has been a significant online source for the myth, having been shared almost a million times by March 2016. [37] The myth has been spread on white nationalist message boards, neo-Nazi websites, the far-right conspiracy website InfoWars, and has been shared millions of times on Facebook. [4]

The myth was shared in the form of a meme, frequently used historical paintings or photographs purposefully misidentified via historical falsifications. For example, images of child labourers, paintings of Roman-era slaves, and photographs of prisoners of war were all falsely captioned as evidence of Irish slaves. [38]

"Almost all of the popular 'Irish slaves' articles are promoted by websites or Facebook groups based in the U.S. So it’s predominantly a social media phenomenon of white America." [33] The myth is especially popular with apologists for the Confederate States of America, the secessionist slave states of the South during the American Civil War. [33]

The myth has been a common trope on the white supremacist website Stormfront since 2003. [39] [40] It has circulated widely in the United States, and has recently begun to become common in Ireland after the "Irish slaves" meme went viral on social media in 2013. [41] [33] After the 2014 arrival of the Black Lives Matter movement, the myth was frequently referenced by right-wing white Americans attempting to undermine it [42] and other African-American civil rights issues, according to Aidan McQuade, director of Anti-Slavery International. [43]

In August 2015, the meme was referred to in the context of debates about the continued flying of the Confederate flag, following the Charleston church shooting. [44] [45]

In May 2016, it was referenced by prominent members of Sinn Féin, after their leader Gerry Adams, "while seeking to compare the treatment of African Americans with Catholics in Northern Ireland", [46] became involved in a controversy over his use of the word " nigger" in a false-equivalence reference to Irish nationalists in Northern Ireland. [3]

Irish Times columnist Donald Clarke criticises the myth as being racist, writing that "more commonly we see racists using the myth to belittle the suffering visited on black slaves and to siphon some sympathy towards their own clan." [47] According to The New York Times, the myth is "often politically motivated" and has been used to create "racist barbs" against African-Americans. [4]

Several online articles about "Irish slaves" substituted the 132 African victims of the 1781 Zong massacre with Irish victims. GlobalResearch.ca and InfoWars, both conspiracy websites, inflated the number from 132 victims to 1,302 during such substitutions. In 2015, independent scholar Liam Hogan theorized that the juxtaposing of the Zong massacre with Irish penal labourers originated with a 2002 article, by James Mullin, then chair of the New Jersey-based Irish Famine Curriculum Committee and Education Fund, titled, "Out of Africa". Though Mullin did not misidentify the victims of the Zong Massacre, his article nevertheless blurred the line between the history of African slavery in colonial America with the history of Irish indentured servants sent to English colonies in North America. [4] [48]

Academic criticism and responses

The Irish Examiner removed an article that cited John Martin's 'Globalresearch.ca' piece from its website in early 2016 after 82 writers, historians and academics wrote an open letter condemning the myth. [49] [4] Scientific American published a blog post in 2015, which was also debunked in the open letter, and later heavily revised the blog to remove the incorrect historical material. [50]

Writing in The New York Times, Liam Stack noted that inaccurate "Irish slavery" claims "also appeared on IrishCentral, a leading Irish-American news website." [51] In 2017 IrishCentral's publisher Niall O'Dowd then wrote an op-ed in which he states that "there is no way the Irish slave experience mirrored the extent or level of centuries-long degradation that African slaves went through." [52] In 2020, the website said that propagation of false social media about Irish slaves are "attempts to trivialize and deny centuries institutionalized, race-based slavery." [53]

Sean O'Callaghan's book To Hell or Barbados in particular has been criticised by, among others, Nini Rodgers, who stated that his narrative appeared to arise from his horror at seeing white people being treated on the same social level with blacks. [54] Bryan Fanning notes the book ignored scholarly research. [1] Anthropologist Mark Auslander states in a 2017 article that the current racial climate is leaning toward denial of certain events in history: "There is a strange war on memory that's going on right now, denying the facts of chattel slavery, or claiming to have learned on Facebook or social media that, say, Irish slavery was worse, that white people were enslaved as well. Not true." [55]

Historians note that unlike slaves, many indentured servants willingly entered into contracts, served for a finite period, did not pass their unfree status on to their children, and were still considered fully human. [4] [56] In Jezebel, Matthew Reilly states clearly: "The Irish slave myth is not supported by the historical evidence. Thousands of Irish were sent to colonies like Barbados against their will, never to return. Upon their arrival, however, they were socially and legally distinct from the enslaved Africans with whom they often labored. While not denying the vast hardships endured by indentured servants, it is necessary to recognize the differences between forms of labor in order to understand the depths of the inhumane system of chattel slavery that endured in the region for several centuries, as well as the legacies of race-based slavery in our own times." [56] According to Hogan, the debate over the exact definition of slavery allowed for a grey area in historical discourse that was then seized upon as a political weapon by white supremacists. [41] [33]

References

- ^ a b c d e Fanning, Bryan (November 1, 2017). "Slaves to a Myth". Irish Review of Books (article). 102. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- ^ a b O'Carroll, Eoin (March 16, 2018). "No, the Irish were not slaves in the Americas". Christian Science Monitor. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ a b c Linehan, Hugh (May 11, 2016). "Sinn Féin Not Allowing Facts Derail Good 'Irish Slaves' Yarn". The Irish Times. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Stack, Liam (March 17, 2017). "Debunking a Myth: The Irish Were Not Slaves, Too". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- ^ a b Handler, Jerome S.; Reilly, Matthew C. (January 1, 2017). "Contesting "White Slavery" in the Caribbean". New West Indian Guide. 91 (1–2): 30–55. doi: 10.1163/22134360-09101056. Archived from the original on June 25, 2020. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- ^ a b Pogachnik, Shawn (March 16, 2017). "AP FACT CHECK: Irish "slavery" a St. Patrick's Day myth". Dublin. Associated Press. Retrieved April 14, 2017 – via The Seattle Times.

- ^ Varner, Natasha (March 16, 2017). "The curious origins of the 'Irish slaves' myth". Public Radio International. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Donaghue, John (July–August 2017). "The curse of Cromwell: revisiting the Irish slavery debate". History Ireland. 25 (4). Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- ^ a b Michael Davitt (May 1904) [begun 1883]. "CHAPTER II. Section I. TORIES AND OUTLAWS". The Fall of Feudalism in Ireland (full text). Retrieved November 11, 2018 – via archive.org.

- ^ "Prostitution". www.femaleconvicts.org.au. Retrieved November 10, 2021.

- ^ Beattie, J.M. (1986), Crime and the Courts in England 1660–1800, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 474, ISBN 0-19-820058-7

- ^ Bartlett, Thomas. "'This famous island set in a Virginian sea': Ireland in the British Empire, 1690–1801." In The Oxford History of the British Empire. Volume II: The Eighteenth Century, by Marshall, P.J., Alaine Low, and Wm. Roger Louis, edited by P.J. Marshall and Alaine Low. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. p. 256.

- ^ "Transportation records (Ireland to Australia) held by the National Archives of Ireland (as filmed by the AJCP)". Trove. Retrieved November 10, 2021.

- ^ a b "'Irish slaves': the convenient myth". openDemocracy. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ Monahan, Michael J. (2011). The Creolizing Subject: Race, Reason, and the Politics of Purity (1st ed.). Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0823234509.

- ^ Christopher Tomlins, "Reconsidering Indentured Servitude: European Migration and the Early American Labor Force, 1600–1775," Labor History (2001) 42#1 pp. 5–43

- ^ Rodgers, Nini (February 28, 2013). "The Irish and the Atlantic slave trade". History Ireland. 15 (3: May/June 2007). Dublin: History Publications, Ltd.

-

^ Hogan, Liam (March 17, 2018).

"No, The Irish Were Not Slaves Too". Pacific Standard. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

In Ireland it was mainly indirect via the provisions trade. It primarily benefited the Protestant Ascendancy, the Catholic elites, and the Catholic middle class who dominated trade in the cities. Many of our merchants (whether Catholic, Protestant, Huguenot, or Quaker) made fortunes trading with all of the slavocracies in the Caribbean.

-

^ Rodgers, Nini (May 1, 2007).

"The Irish and the Atlantic slave trade". History Ireland. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

The eighteenth-century economies of Cork, Limerick and Belfast expanded on the back of salted and pickled provisions specially designed to survive high temperatures. These were exported to the West Indies to feed slaves and planters, British, French, Spanish and Dutch. Products grown on slave plantations, sugar in the Caribbean and tobacco from the North American colonies, poured into eighteenth-century Ireland. Commercial interests throughout the island, and the parliament in Dublin, were vividly aware of how much wealth and revenue could be made from the imports.

- ^

a

b Ohlmeyer, Jane (March 12, 2021).

"Ireland, Empire, and the Early Modern World: watch the lectures". RTE. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

By 1660 Irish people, mostly men, were to be found in the French Caribbean, the Portuguese and later Dutch Amazon, Spanish Mexico, and the English colonies in the Atlantic and Asia where they joined colonial settlements, served as soldiers and clergymen, forged commercial networks as they traded calicos, spices, tobacco, sugar, and slaves.

-

^ Rodgers, Nini (2007).

"The Irish in the Caribbean 1641 -1837: An Overview" (PDF). Irish Migration Studies in Latin America. 5 (3): 150. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

To make this journey in reverse became more common as the Irish merchant community on the Atlantic coast found itself at the centre of France's slave trade and sugar imports. Back in France, money from the slave trade and plantations helped to fund the Irish college in Nantes and Walsh's regiment in the Irish brigade, which received its name from Antoine's nephew, coming from a new generation determined to put trade behind them. Despite enormous losses in both areas during the upheavals of the Revolution, these families survive today in France as titled and chateaux-owning.

- ^ Akenson, Donald (1997). If the Irish Ran the World: Montserrat, 1630-1730. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0773516304.

- ^ Kelly, Brian (January–February 2021). "Empire, inequality, and Irish complicity in slavery". History Ireland: 14–15 – via academia.edu.

- ^ "Ireland and Slavery: Framing Irish Complicity in the Slave Trade". CounterPunch.org. August 7, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ "Framing Irish Complicity in the Slave Trade". REBEL. July 13, 2020. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ Kennedy, Liam (2015). Unhappy the Land: The Most Oppressed People Ever, the Irish?. Dublin: Irish Academic Press. p. 19. ISBN 9781785370472.

- ^ Carroll, Rory (March 7, 2021). "Trinity College reckons with slavery links as Ireland confronts collusion with empire". The Guardian. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved March 25, 2021.

- ^ Linehan, Hugh. "Sinn Féin not allowing facts derail good 'Irish slaves' yarn". The Irish Times. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

-

^

Barkun, Michael (2003).

"Millennialism, Conspiracy, and Stigmatized Knowledge".

A Culture of Conspiracy: Apocalyptic Visions in Contemporary America. University of California Press. p. 34.

ISBN

9780520238053. Retrieved March 15, 2013.

Michael A. Hoffman II, a Holocaust denier and exponent of multiple conspiracy theories

- ^ "Ernst Zundel interviews Michael A. Hoffman author of They Were White and They Were Slaves". DavidDuke.com. April 20, 2008.

- ^ Hogan, Liam; McAtackney, Laura; Reilly, Matthew C. (February 29, 2016). "The Irish in the Anglo-Caribbean: Servants or Slaves?". History Ireland.

- ^ "The O'Brien Press - To Hell or Barbados - The ethnic cleansing of Ireland By Sean O'Callaghan". www.obrien.ie. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Amend, Alex. "How the Myth of the "Irish slaves" Became a Favorite Meme of Racists Online". Hatewatch (blog). Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

-

^ Kelleher, Lawrence R. (January 15, 2001).

To Shed a Tear: A Story of Irish Slavery in the British West Indies. Writers Club Press. p. 73.

ISBN

0595169260.

Some of the physically larger blacks were made guards and were given certain privileges, namely Irish women. There had been several Irish killed trying to protect the Irish women from being assaulted by these savage blacks.

-

^ Nixon, Guy (2011).

Slavery in the West: The Untold Story of the Slavery of Native Americans in the West. Xlibris Corporation. p. 12.

ISBN

9781462865253.

This African would serve as a stud for the inexpensive Irish women slaves…[these breeding programs were stopped] because it was reducing the profits of the Royal African Company…[but] due to the profitability of these breeding programs the practice continued until well after the end of Ireland's 'Potato Famine'.

- ^ "Ireland and Slavery: Debating the 'Irish Slaves Myth'". CounterPunch.org. August 6, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ Costello, Norma (March 17, 2016). "Black Lives Matter and the 'Irish slave' Myth". aljazeera.com. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- ^ "Debunking the Imagery of the 'Irish Slaves' Meme". ShowerOfKunst.com. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ Riley, Ricky (March 18, 2016). "Myth Busted: Scholars Fire Back Against Memes Pushing Narrative of Irish Slaves in the Americas". atlantablackstar.com. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- ^ Deignan, Tom (May 7, 2016). "Racial Tensions of 2016 and the Myth of Irish Slavery - Opinion". nj.com. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- ^ a b Hogan, Liam (January 12, 2015). "'Irish Slaves': The Convenient Myth". opendemocracy.net. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- ^ Kireini, Douglas (March 8, 2018). "Any attempts to rewrite history must be rebuffed". Business Daily. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ Ferguson, Amanda (May 2, 2016). "Adams Comparing US Slavery with Nationalist Plight 'Overblown'". The Irish Times. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- ^ Tucker, Neely (August 18, 2015). "In Mississippi, Defenders of State's Confederate-Themed Flag Dig In". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

-

^ Hogan, Liam; McAtackney, Laura; Reilly, Matthew Connor (October 6, 2015).

"The Unfree Irish in the Caribbean Were Indentured Servants, Not Slaves". Yahoo News. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

Inevitably the myth gained prominence in the wake of Dylann Roof's terrorist attack in Charleston and the subsequent debate about the Confederate flag.

- ^ "Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams apologises for racial slur". www.yahoo.com. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ Clarke, Donald (July 30, 2016). "Free Us From Myth of US Irish Slavery". The Irish Times. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ Mullin, James. "Out of Africa, Out of Ireland". Archived from the original on October 27, 2002.

- ^ Dempsey, James (March 9, 2016). "Irish Historians Add Their Names to Open Letter Criticising the "Racist Propaganda" of 'Irish slavery'". Newstalk. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- ^ D'Costa, Krystal (March 17, 2015). "It's True: We're Probably All a Little Irish—Especially in the Caribbean". blogs.scientificamerican.com. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

-

^ Stack, Liam (March 17, 2017).

"Debunking a Myth: The Irish Were Not Slaves, Too". NY Times. Retrieved July 29, 2018.

Mr. O'Callaghan's work was repeated or repackaged on Irish genealogy websites, in a popular online essay, and in articles in publications like Scientific American and The Daily Kos. The claims also appeared on IrishCentral, a leading Irish-American news website.

-

^ O'Dowd, Niall (March 30, 2017).

"Why the Irish were both slaves and indentured servants in colonial America". Irish Central. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

The controversy has arisen because some far-right groups have claimed that the experience of Irish slaves was interchangeable with (or even in some cases worse than) the experience of black slaves, and have used that as justification for an array of abhorrent racist statements and ideas. To be clear, there is no way the Irish slave experience mirrored the extent or level of centuries-long degradation that African slaves went through. But the Irish did suffer tremendously and there is a clear tendency to undermine that truth. Adults and children were torn from their homes, transported to the colonies in bondage against their will, and sold into a system of prolonged servitude. Some would even call it slavery.

- ^ O'Brien, Shane (July 2, 2020). "Facebook post falsely claiming Irish were slaves shared one million times". IrishCentral.com. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ Rodgers, Nini (January 31, 2007). Ireland, Slavery and Anti-Slavery. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-77099-3.

- ^ Eversley, Melanie (February 17, 2017). "Slavery-Era Embroidery Excites Historians, Evokes Heartbreak of Its Time". USA Today. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- ^ a b Davies, Madeleine (March 17, 2016). "Let's Squash the Myth That the Irish Were Ever American Slaves". jezebel.com.

Further reading

- Brown, Matthew (June 16, 2020). "Fact check: The Irish were indentured servants, not slaves". USA Today. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- Cadier, Alex (July 7, 2020). "More false claims about 'Irish slaves' spread on social media". AFP Fact Check. Agence France-Presse. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- Johnson, Robert (2018). "What to Do about the Irish in the Caribbean?". Caribbean Quarterly. 64 (3–4): 409–433. doi: 10.1080/00086495.2018.1531554. S2CID 165509275.

- Johnson, Robert Allen (2019). "The Irish as Caribbean Slaves? Meme, Internet Meme and Intervention". Imaginaires (22): 159–176. doi: 10.34929/imaginaires.vi22.12. ISSN 2780-1896.

- "Fact check: 'Irish slaves' meme repeats discredited article". Reuters. June 19, 2020. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- "Fact check: First slaves in North American colonies were not "100 white children from Ireland"". Reuters. June 19, 2020. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

External links

- The Irish Slaves Myth, The Irish Passport podcast.

- Anti-black racism in Europe

- Anti-black racism in the United States

- Historiography of Ireland

- History of slavery

- Indentured servitude in the Americas

- Irish-American history

- Irish diaspora in the Caribbean

- Irish diaspora in North America

- Irish nationalism

- Penal labour

- Propaganda in the United States

- Pseudohistory

- White nationalism in the United States

- White supremacy

- Victimology