This article needs additional citations for

verification. (June 2022) |

The history of local government in England is one of gradual change and evolution since the Middle Ages. England has never possessed a formal written constitution, with the result that modern administration (and the judicial system) is based on precedent, and is derived from administrative powers granted (usually by the Crown) to older systems, such as that of the shires.

The concept of local government in England spans back into the history of Anglo-Saxon England (c. 700-1066), and certain aspects of its modern system are directly derived from this time; particularly the paradigm that towns and the countryside should be administrated separately. In this context, the feudal system introduced by the Normans, and perhaps lasting 300 years, can be seen as a 'blip', before earlier patterns of administration re-emerged.

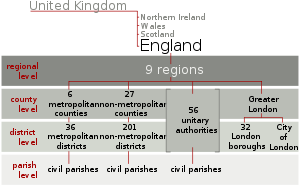

The dramatic increase in population, and change in population distribution caused by the Industrial Revolution necessitated similarly dramatic reform in local administration in England, which was achieved gradually throughout the 19th century. Much of the 20th century was spent searching for an idealised system of local government. The most sweeping change in that period was the Local Government Act 1972, which resulted in a uniform two-tier system of counties and districts being introduced in 1974; however, further waves of reform have led to a more heterogeneous system in use today.

Origins of local government in England

This original research needs additional citations for

verification. (March 2020) |

Much of the basic structure of local government in England is derived directly from the Kingdom of England (which became part of the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707 then later part of the United Kingdom). There are thus aspects of the modern system which are not shared with the other constituent parts of the UK, namely Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The Kingdom of England was by origin an extension of the Saxon Kingdom of Wessex into the other regions, supplanting amongst others the former kingdoms of Mercia, Northumbria and Kingdom of East Anglia, and unifying the Anglo-Saxon peoples of the British Isles. Some of the basic elements of modern local government therefore derive from the ancient system of Wessex.

Anglo-Saxon local government (700–1066 AD)

The Kingdom of Wessex, c. 790 AD, was divided into administrative units known as shires. Each shire was governed by an Ealdorman, a major nobleman of Wessex appointed to the post by the King. The term 'Ealdorman' (meaning 'elder-man') gradually merged with the Scandinavian Eorl/Jarl (designating an important chieftain), to form the modern 'Earl'. However, the Shires were not comparable with later Earldoms, and were not held in the Ealdorman's own right; the position was appointive, rather than a hereditary title of nobility.

The shires of Wessex at this time have essentially survived to the present day, as counties of England (currently ceremonial counties). They included Defnascir ( Devon), Sumorsaete ( Somerset), Dornsaete ( Dorset), Wiltunscir ( Wiltshire), Hamptunscir ( Hampshire). When Wessex conquered the petty kingdoms of southern England, namely Kent and that of the South Saxons, these were simply reconstituted as shires (modern Kent and Sussex respectively).

As Wessex took over progressively larger areas of Mercia, East Anglia and Northumbria, the new lands were divided into shires, usually named after the principal town in the new shire; hence Northamptonshire, Oxfordshire, Derbyshire and so on. Most of the historic counties of England (and modern Ceremonial counties) south of the Mersey and Humber derive directly from this time.

Another important shire official was the shire-reeve; the modern day derivative is a sheriff or high sheriff. The shire-reeve was responsible for upholding the law, and holding civil and criminal courts in the shire. [1] The office of sheriff is still important in some Anglophone countries (e.g. the United States), but now a ceremonial role in England.

Below the level of the shire, the Anglo-Saxon system was very different from the later systems of local government. The shire was divided into an unlimited number of hundreds (or wapentakes in the Danelaw counties of Yorkshire, Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Northamptonshire, Nottinghamshire, Rutland and Lincolnshire). Each hundred consisted of 10 groups of 10 households. A group of 10 households was a tithing and each household held one hide of land. The hide was an arbitrary unit of land which was deemed able to support one household, and thus could vary in size. The whole hundred system was thus both very flexible and fluid, varying with changes in population etc.

Hundreds were led by a 'hundred-man', and had their own 'hundred' courts. The members of the hundreds (or tithings, etc.) were collectively held responsible for each individual's conduct, thereby decentralising the administration of justice upon the people themselves. Hundreds were used as administrative units for the raising of armies, collection of taxes and so forth.

The Norman conquest (1066–1100)

The conquest of England by the Normans in 1066 brought about many changes in the local administration of the country, but some aspects were retained. One of the biggest changes was the introduction of a severe feudal system by the Normans. Although Anglo-Saxon society had also been essentially feudal in character, the Norman system was much more rigid, centralised and thorough. William the Conqueror claimed ultimate possession of virtually all the land in England and asserted the right to dispose of it as he saw fit. Thenceforth, all land was "held" from the King. [2] The country was divided up into fiefs which William distributed amongst his followers. The fiefs were generally small and given out piecemeal, to deprive William's vassals of large power-bases.

Since each fiefdom was governed more or less independently of each other by the feudal lords, the Anglo-Saxon shire system became less important. However, the system did continue in use. The shires (referred to by the Normans as 'counties', in analogy to the system in use in medieval France) remained the major geographical division of England. North of the Humber, the Normans reorganised the shires to form one new large county, that of Yorkshire. Immediately after the conquest the rest of northern England does not seem to have been in Norman hands; as the remainder of England came under Norman rule it too was also constituted into new counties (e.g. Lancashire, Northumberland) In the period immediately after the Norman conquest, hundreds also remained as the basic administrative unit. In the Domesday Book, the great Norman work of bureaucracy, the survey is taken shire by shire, and hundred by hundred. At this time, if not before, hundreds must have become more static units of land, since the more fluid nature of the original system would not have been compatible with the rigid feudal system of the Normans. Although hundreds continued to alter in size and number after the Domesday Book, they became more permanent administrative divisions, rather than groups of households.

The Early Middle Ages (1100–1300)

During the Middle Ages local administration remained in the hands of the feudal lords, who governed affairs in their fiefs. The enserfment of the population by the Norman system diminished the importance of hundreds as self-regulating social units since law was not imposed from above, and since the population was immobilised. Instead the basic social unit became the parish, manor or township.

The counties remained important as the basis for the legal system. The sheriff remained the paramount legal officer in each county, and each county eventually had its own court system for trials (the quarter sessions). Although the hundred courts continued in use resolving local disputes, they diminished in importance. During the reigns of Henry III, Edward I, and Edward II a new system emerged. Knights in each county were appointed as Conservator of the Peace, being required to help keep the King's Peace. Eventually they were given the right to try petty offences which had formerly been tried in the hundred courts. These officers were the forerunners of the modern magistrates' courts and justices of the peace.

The rise of the town

The feudal system introduced by the Normans was designed to govern rural areas which could easily be controlled by a lord. Since the system was based on the exploitation of the labour and produce of enserfed peasant farmers, the system was unsuited to governing larger towns, which had more complex economies and a greater population of free (non-serf) people. At the time of the Norman conquest true urban centres were few in England, but during the early medieval period a growing population and increased mercantile activity led to an increase in the importance of towns.

London, by far the largest settlement in England during the medieval period, had been marked out for special status as early as the reign of Alfred the Great. William the Conqueror granted London a royal charter in 1075, confirming some of the autonomy and privileges that the city had accumulated during the Saxon period. The charter gave London self-governing status, paying taxes directly to the king in return for remaining outside the feudal system. The citizens were therefore 'burgesses' rather than serfs, and in effect free men. William's son Henry I granted charters to other towns, often to establish market towns.

However, it was Henry II who greatly expanded the separation of towns from the countryside. He granted around 150 royal charters to towns around England, which were thereafter referred to as ' boroughs'. [3] For an annual rent to the crown, the towns were given various privileges, such as the exemption from feudal dues, the right to hold a market and the rights to levy certain taxes. It should be noted however, that not all market towns established during this period were self-governing.

The self-governing boroughs are the first recognisably modern aspect of local government in England. Generally they were run by a town corporation, made up of council aldermen, the town 'elders'. Although each corporation was different, they were usually self-elected, new members being co-opted by the existing members. A mayor was often elected by the council to serve for a given period. The idea of a town council to run the affairs of an individual town remains an important tenet of local government in England today.

Political representation

The English Parliament developed during the 13th century, and would eventually become the de facto governing body for the country. In 1297, it was decreed that the representatives to the House of Commons would be allocated based on the administrative units of counties and boroughs — two knights from each shire, and two burgesses from each borough. This system would remain essentially unchanged (despite massive increases in population in some non-borough areas, and the decreased importance of some boroughs) until the Reform Act of 1832.

The Later Middle Ages (1300–1500)

The decline of the feudal system

By the beginning of the 14th century, the feudal system in England was in decline; the Black Death (1348–1350) causing mass depopulation, is widely held to signal the effective end of feudalism. Thereafter the relationship between lord and vassal become more a relationship between landlord and tenant. The breakdown of the feudal power left the shires without de jure administration. The legal system and sheriffs remained for each county, and what local administration was required was undoubtedly provided by individual parishes or by the local landowners. In an era of very 'small government', the requirement for higher levels of administration was probably minimal. In towns, where more governance would have been required, the town councils continued to manage local affairs.

Counties corporate

A further extension of the borough system occurred in the later medieval period. While borough status gave towns specific rights within counties, some cities petitioned for greater independence. Those cities (or towns) were therefore awarded complete effective independence from the county including their own sheriffs, quarter sessions and other officials, and were sometimes given governing rights over a swath of surrounding countryside. They were referred to in the form "Town and County of ..." or "City and County of ...", and became known as the counties corporate. They included the City and County of York, Bristol, Canterbury and Chester.

Other counties corporate were created to deal with specific local problems, such as border conflict (in the case of Berwick-upon-Tweed) and piracy (in the case of Poole and Haverfordwest).

Later changes in local government (1500–1832)

In the 1540s the office of lord-lieutenant was instituted in each county, effectively replacing feudal lords as the Crown's direct representative in that county. The lieutenants had a military role, previously exercised by the sheriffs, and were made responsible for raising and organising the county militia. The county lieutenancies were subsequently given responsibility for the Volunteer Force. In 1871 the lieutenants lost their position as head of the militia, and the office became largely ceremonial. [4] The Cardwell and Childers Reforms of the British Army linked the recruiting areas of infantry regiments to the counties.

| County Rates Act 1738 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act for the more easy assessing, collecting, and levying, of County Rates. |

| Citation | 12 Geo. 2. c. 29 |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 13 June 1739 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repealed by | Highways Act 1959 |

Status: Repealed | |

From the 16th century the county was increasingly used as a unit of local government. Although 'small government' was still the accepted norm, there were an increasing number of responsibilities which could not be fulfilled by individual communities. The justices of the peace therefore took on various administrative functions known as "county business". This was transacted at the quarter sessions, summoned four times a year by the lord-lieutenant. By the 19th century the county magistrates exercised powers over the licensing of alehouses, the construction of bridges, prisons and asylums, superintendence of main roads, public buildings and charitable institutions, and the regulation of weights and measures. [5] The justices were empowered to levy local taxes to support these activities, and in 1739 under the County Rates Act 1738 ( 12 Geo. 2. c. 29) these were unified as a single "county rate" under the control of a county treasurer. [6] In order to build and maintain roads and bridges, a salaried county surveyor was to be appointed. [7]

These county functions were attached to the legal system, since this was the only body which acted county-wide at that time. However, in this ad hoc system the beginnings of county councils, another central element in modern local government, can be observed. The counties themselves remained more-or-less static between the Law in Wales Acts of 1535–42, and the Reform Act 1832.

Parishes

The ecclesiastical parishes of the Church of England also came to play a de jure roles in local government from this time. It is probable that this merely confirmed the status quo — people of rural communities would have taken care of what local administration was required. Although the parishes were in no sense governmental organisations, laws were passed requiring parishes to carry out certain responsibilities. From 1555, parishes were responsible for the upkeep of nearby roads. From 1605 parishes were responsible for administering the Poor Law, and were required to collect money for their own poor. The parishes were run by parish councils, known as Select Vestries. Some such councils were elective, while others were sustained by co-option (existing members filling vacancies by invitation).

The evolution of modern local government (1832-1974)

The Great Reform Act 1832

The development of modern government in England began with the Great Reform Act of 1832. The impetus for this act was provided by corrupt practices in the House of Commons, and by the massive increase in population occurring during the Industrial Revolution. Boroughs and counties were generally able to send two representatives to the Commons. Theoretically, the honour of electing members of Parliament belonged to the wealthiest and most flourishing towns in the kingdom, thus, boroughs that ceased to be successful could be disenfranchised by the Crown. [8] In practice, however, many tiny hamlets became boroughs, especially between the reigns of Henry VIII and Charles II. Likewise, boroughs that had flourished during the Middle Ages, but had since fallen into decay, were allowed to continue sending representatives to Parliament. The royal prerogative of enfranchising and disfranchising boroughs fell into disuse after the reign of Charles II; as a result, these historical anomalies became set in stone. [9]

In addition, only male owners of freehold property or land worth at least forty shillings in a particular county were entitled to vote in that county; but those who owned property in multiple constituencies could vote in every constituency for which he owned sufficiently valuable property; there was normally no requirement for an individual to actually inhabit a constituency in order to vote there. The size of the English county electorate in 1831 has been estimated at only 200,000. [10] This meant that the very wealthy formed the majority of the electorate and could often vote multiple times. In small boroughs that had fallen into decay, there were often only a handful of eligible voters; these “rotten” boroughs were therefore effectively controlled by the local aristocracy.

The Reform Act (and its successors) attempted to address these issues, by abolishing rotten boroughs (as both constituencies and administrative units), enfranchising the industrial towns as new parliamentary boroughs, increasing the proportion of the population eligible to vote, and ending corrupt practices in parliament. Although this did not directly affect local government, it provided impetus to reform outdated, obsolete and unfair practices elsewhere in government.

The Municipal Corporations Act 1835

After the reform of parliamentary constituencies the boroughs established by royal charter during the previous seven centuries were reformed by the Municipal Corporations Act 1835. The Act required members of town councils ( municipal corporations) in England and Wales to be elected by ratepayers and councils to publish their financial accounts.

Before the passing of the Act, the municipal boroughs varied depending upon their charters. In some boroughs, corporations had become self-perpetuating oligarchies, with membership of the corporation being for life, and vacancies filled by co-option.

The Act reformed 178 boroughs immediately; there remained more than one hundred unreformed boroughs, which generally either fell into desuetude or were replaced later under the terms of the Act. The last of these were not reformed or abolished until 1886. The City of London remains unreformed to the present day. The Act allowed unincorporated towns to petition for incorporation. The industrial towns of the Midlands and North quickly took advantage of this, with Birmingham and Manchester becoming boroughs as soon as 1838. Altogether, 62 additional boroughs were incorporated under the act. With this Act, the boroughs (thereafter “municipal boroughs”) began to take a more noticeably modern and democratic form.

Public welfare reforms

During the industrial revolution there were massive population increases, massively increased urbanisation (especially in previously unimportant towns), and the creation of an urban poor, who had no means of subsistence. This created many new problems that the small-scale local government apparatus existing in England could not cope with. Between 1832 and 1888, several laws were passed to try and address these problems.

In 1837 laws were passed allowing rural parishes to group together as poor law unions, in order to administer the Poor Law more effectively; these unions were able to collect taxes (“rates”) in order to carry out poor-relief. Each union was run by a Board of Guardians, partly elected but also including local justice of the peace. In 1866, all land which was not part of ecclesiastical parishes was formed into Civil Parishes for administration of the poor law. In the municipal boroughs the poor law was administered by the town corporation.

The Public Health Act 1848 was passed, establishing a local board of health in towns, to regulate sewerage and the spread of diseases. In municipal boroughs, the town corporation selected the board; in other urban areas, the rate-payers elected the boards. Although the boards had legal powers, they were non-governmental organisations.

In 1873 and 1875, further Public Health Acts (the Public Health Act 1873 and Public Health Act 1875 ( 38 & 39 Vict. c. 55)) were passed, which established new quasi-governmental organisations to administer both the poor law, and public health and sanitation. Urban sanitary districts were created from the local boards of health, and continued to be run by in similar fashion. Rural sanitary districts were created from the Poor Law Unions, and, again were similarly governed.

Expansion of the franchise

In local government elections, unmarried women ratepayers received the right to vote in the Municipal Franchise Act 1869. This right was confirmed in the Local Government Act 1894 ( 56 & 57 Vict. c. 73) and extended to include some married women. [11] [12] [13] By 1900, more than 1 million women were registered to vote in local government elections in England. [14]

The Local Government Acts 1888 and 1894, and the London Government Act 1899

By 1888 it was clear that the piecemeal system that had developed over the previous century in response to the vastly increased need for local administration could no longer cope. The sanitary districts and parish councils had legal status, but were not parts of the mechanism of government. They were run by volunteers, and often there was no-one who could be held responsible for the failure to undertake the required duties. The increased "county business" could not be handled by the Quarter Sessions, nor was it appropriate to do so. Finally, there was a desire to see local administration performed by elected officials, as in the reformed municipal boroughs. The Local Government Act was therefore the first systematic attempt to impose a standardised system of local government in England.

The Act established county councils as well as newly created areas for those councils, to be known as administrative counties. These new administrative counties were based on the historic counties, [15] which had been used in the local government structure until then. These statutory administrative counties were also to be used for non-administrative functions: " sheriff, lieutenant, custos rotulorum, justices, militia, coroner, or other". With the advent of elected councils, the offices of lord lieutenant and sheriff became largely ceremonial.

The statutory counties formed the basis for the so-called “administrative counties”. However, it was felt that large cities and primarily rural areas in the same county could not be well administered by the same body. Thus 59 “counties in themselves”, or “county boroughs”, were created to administer the urban centres of England. These were parts of the statutory counties, but not parts of the administrative counties. The qualifying limit for county borough status was a population of 50,000, although some historic towns, such as Canterbury and Oxford, were given county borough status despite having lower populations. Each administrative county and county borough was governed by an elected county or borough council, providing services specifically for its own area.

The Act also created a new County of London from the urban areas of London, which was a full statutory county by itself with no historical basis. Its new county council absorbed the Metropolitan Board of Works, which had been established in 1855 specifically to maintain the infrastructure of London.

By this time many towns possessed liberties and franchises from royal charters and grants that were anomalous, obsolete or otherwise irrelevant, but nevertheless often cherished by the townspeople. Some of these towns were municipal boroughs, in which case the powers remained with the municipal corporation. However, there were others, such as the Cinque Ports, which were not boroughs. Rather than abolish these rights and powers, the Act directed that the powers should be taken over by the new county councils or county borough councils. Although counties corporate were not abolished by the act, their administration was taken over by their parent administrative county or county borough. The act therefore abolished them in all but name, though they still appointed their own sheriffs, and each continued to described itself, for purely ceremonial purposes, as a "county and city".

A second act in 1894, the Local Government Act 1894 ( 56 & 57 Vict. c. 73), created a second tier of local government by dividing all administrative counties into either rural or urban districts, allowing more localised administration. (The county boroughs were never divided in this way.) The municipal boroughs reformed after 1835 were brought into this system as special cases of urban districts. The urban and rural districts were based on, and incorporated, the sanitary districts created in 1875, with adjustments so that districts did not cross any county boundaries.

The act of 1894[ which?] also provided for the establishment of civil parishes, separated from the ecclesiastical parishes, to carry on some of their responsibilities, others being transferred to the district or county councils. However, the civil parishes were not a complete third tier of local government, since they were established only for smaller rural settlements with 100 residents or more, while the older urban parish councils were absorbed into the new urban districts.

A final relevant piece of legislation, the London Government Act 1899, divided the new County of London into districts, known (rather confusingly) as Metropolitan Boroughs.

Attempts at reform (1945-1974)

Initially the new administrative system worked quite well, and several more county boroughs were created in the next decades. However, from 1926 the population requirement increased to 75,000. There was also some concern about the viability of some county boroughs which had declined since 1888. For instance, viability of the county borough of Merthyr Tydfil came into question in the 1930s. Due to a decline in the heavy industries of the town, by 1932 more than half the male population was unemployed, resulting in very high municipal rates in order to make public assistance payments. At the same time the population of the borough was lower than when it had been created in 1908. [16] A royal commission was appointed in May 1935 to "investigate whether the existing status of Merthyr Tydfil as a county borough should be continued, and if not, what other arrangements should be made". [17] The commission reported the following November, and recommended that Merthyr should revert to the status of a non-county borough, and that public assistance should be taken over by central government. In the event county borough status was retained by the town, with the chairman of the Welsh Board of Health appointed as administrative adviser in 1936. [18]

Local governments across the United Kingdom lost power after the Labour Party won the 1945 general election and formed its first majority government under Clement Attlee. Under Labour's postwar social and economic reforms functions traditionally operated by local governments such as gas, electricity, and hospitals were nationalized under regional boards or national government institutions such as the National Health Service. [19] After the Second World War the creation of new county boroughs in England and Wales was effectively suspended, pending a local government review. A government white paper published in 1945 stated that "it is expected that there will be a number of Bills for extending or creating county boroughs" and proposed the creation of a boundary commission to bring coordination to local government reform. The policy in the paper also ruled out the creation of new county boroughs in Middlesex "owing to its special problems". [20] The Local Government Boundary Commission was appointed on 26 October 1945, under the chairmanship of Sir Malcolm Trustram Eve, [21] delivering its report in 1947. [22] The Commission recommended that towns with a population of 200,000 or more should become one-tier "new counties", with "new county boroughs" having a population of 60,000 - 200,000 being "most-purpose authorities", with the county council of the administrative county providing certain limited services. The report envisaged the creation of 47 two-tiered "new counties", 21 one-tiered "new counties" and 63 "new county boroughs". The recommendations of the Commission extended to a review of the division of functions between different tiers of local government, and thus fell outside its terms of reference, and its report was not acted upon.

The next attempt at reform was by the Local Government Act 1958, which established the Local Government Commission for England and the Local Government Commission for Wales to carry out reviews of existing local government structures and recommend reforms. Although the Commissions did not complete their work before being dissolved, a few new county boroughs were constituted between 1964 and 1968. Luton, Torbay, and Solihull gained county borough status. Additionally, Teesside county borough was formed from the merger of the existing county borough of Middlesbrough, and the non-county boroughs of Stockton-on-Tees and Redcar; Warley was formed from the county borough of Smethwick and the non-county boroughs of Oldbury and Rowley Regis; and West Hartlepool was merged with Hartlepool. Following these changes, there were a total of 79 county boroughs in England. The Commission also recommended the downgrading of Barnsley to be a non-county borough, but this was not carried out. The commission did succeed in merging two pairs of small administrative counties to form Huntingdon and Peterborough and Cambridgeshire and Isle of Ely.

In 1965 a major reform in London was undertaken in reflection of the size and specific problems of the city. The administrative counties of London and Middlesex were abolished, and their area were joined with parts of Essex, Surrey and Kent to form into a new county of Greater London. Greater London was divided into 32 London Boroughs, replacing both the old Metropolitan Boroughs of Inner London (the area of the old London County Council) and the county boroughs and urban districts of Outer London.

The Local Government Commission was wound up in 1966, and replaced with a Royal Commission (known as the Redcliffe-Maud commission). In 1969 it recommended a system of single-tier unitary authorities for the whole of England, apart from three metropolitan areas of Merseyside, Selnec (Greater Manchester) and West Midlands ( Birmingham and the Black Country), which were to have both a metropolitan council and district councils. This report was accepted by the Labour Party government of the time despite considerable opposition, but the Conservative Party won the June 1970 general election, and on a manifesto that committed them to a two-tier structure.

The Local Government Act 1972

The reforms arising from the Local Government Act of 1972 resulted in the most uniform and simplified system of local government used in England so far. They effectively wiped away everything that had gone before and built an administrative system from scratch. All previous administrative districts - statutory counties, administrative counties, county boroughs, municipal boroughs, counties corporate, civil parishes - were abolished, with the exceptions of Greater London and the Isles of Scilly.

The aim of the Act was to establish a uniform two-tier system across the country. New counties were created to cover the entire country. Many of these were based on the historic counties, but there were some major changes, especially in the North. The tiny county of Rutland was joined with Leicestershire; Cumberland, Westmorland and the Furness exclave of Lancashire were fused into the new county of Cumbria; Herefordshire and Worcestershire were joined to form Hereford & Worcester; the three ridings of Yorkshire were replaced by North, South and West Yorkshire, along with Humberside. The Act also created six new metropolitan counties, modelled on Greater London, to address the problems of administering large conurbations; these were Greater Manchester, Merseyside, Tyne & Wear, West Yorkshire, South Yorkshire and the West Midlands. The new counties of Avon (the city of Bristol, North Somerset and South Gloucestershire), Cleveland (the Teesside area) and Humberside were designed with the idea of uniting areas based on river estuaries.

Each of the new counties was then endowed with a county council to provide certain county-wide services such as policing, social services and public transport. The Act substituted the new counties "for counties of any other description" for purposes of law. [23] The new counties therefore replaced the statutory counties created in 1888 for judicial and ceremonial purposes (such as lieutenancy, custodes rotulorum, shrievalty, commissions of the peace and magistrates' courts); [24] [25] and replaced administrative counties and county boroughs for administrative purposes.

The second tier of the local government varied between the metropolitan and non-metropolitan counties. The metropolitan counties were divided into metropolitan boroughs, whilst the non-metropolitan counties were divided into districts. The metropolitan boroughs had greater powers than the districts, sharing some of the county council responsibilities with the metropolitan county councils, and having control of others that districts did not (e.g. education was administered by the non-metropolitan county councils, but by the metropolitan borough councils). The metropolitan boroughs were supposed to have a minimum population of 250,000 and districts 40,000; in practice some exceptions were allowed for the sake of convenience.

Where municipal boroughs still existed, they were dissolved. However, the charter grants made to those boroughs (where transfer had not already occurred), were generally transferred to the district or metropolitan borough which contained area in question. Districts which succeeded to such powers were permitted to style themselves 'borough councils' as opposed to 'district councils' - however, the difference was purely ceremonial. The powers of some municipal boroughs were transferred to either civil parish councils, or to charter trustees; see Borough status in the United Kingdom for details.

The act also dealt with civil parishes. These were maintained in rural areas, but those existing in large urban areas were abolished. Conversely, the Act actually provided the legislation such that the whole country could be divided into parishes if this was desirable at some point in the future. However, at the time urban parishes were strongly discouraged. However, since 1974, several urban areas have applied for and received parish councils. Much of the country remains unparished, since the parish councils are not a necessary part of local government, but exist to give civic identity to smaller settlements.

The new system of local government came into force on 1 April 1974, but in the event the uniformity proved to be short lived.

Further reform (1974-)

Abolition of the metropolitan county councils

This uniform two-tier system lasted only 12 years. In 1986, the metropolitan county councils and Greater London were abolished under the Local Government Act 1985. This restored autonomy (in effect the old county borough status) to the metropolitan and London boroughs. While the abolition of the Greater London Council was highly controversial, the abolition of the MCCs was less so. The government's stated reason for the abolition of the MCCs, in its 1983 white paper Streamlining the cities, was based on efficiency and their overspending. However the fact that all of the county councils were controlled at the time by the opposition Labour Party led to accusations that their abolition was motivated by party politics: the general secretary of NALGO described it as a "completely cynical manoeuvre". [26] [27] This created an unusual situation where seven counties had, administratively, ceased to exist, but the area had not been annexed to any other county. The metropolitan counties thus continued to exist as geographical entities, and lived a shadowy semi-existence, since services such as the police force continued to call themselves e.g. 'Greater Manchester Police'. This gave rise to the concept of the ' ceremonial county'. From a geographical and ceremonial point of view, England continues to be made up of the counties established in 1974, with one or two exceptions (see below). These counties still have a lord lieutenant and sheriff, and are therefore usually referred to as ceremonial counties.

Local Government Act (1992)

By the 1990s, it was apparent that the 'one-size fits all' approach of the 1974 reforms did not work equally well in all cases. The consequent loss of education, social services and libraries to county control, was strongly regretted by the larger towns outside the new metropolitan counties, such as Bristol, Plymouth, Stoke, Leicester and Nottingham. [28] [29] The abolition of metropolitan county councils in 1986 had left the metropolitan boroughs operating as 'unitary' (i.e., only one tier) authorities, and other large cities (and former county boroughs) wished for a return to unitary governance.

The Local Government Act (1992) established a commission ( Local Government Commission for England) to examine the issues, and make recommendations on where unitary authorities should be established. It was considered too expensive to make the system entirely unitary, and also there would doubtlessly be cases where the two-tier system functioned well. The commission recommended that many counties be moved to completely unitary systems; that some cities become unitary authorities, but that the remainder of their parent counties remain two-tier; and that in some counties the status quo should remain.

The first major changes to be recommended were for unpopular new counties created in 1974. Three of these had artificially united the areas around rivers/estuaries ( Cleveland, Humberside and Avon), and the commission recommended that they be split into four new unitary authorities. This effectively gave a 'metropolitan borough-like' status to the cities of Hull, Bristol and Middlesbrough. It also restored the East Riding of Yorkshire as a de facto county. Rutland was reestablished as a unitary authority, thus regaining its cherished 'independence' from Leicestershire. The merged county of Hereford & Worcester was restored to Herefordshire (as a unitary authority) and Worcestershire (as a two-tier authority).

The only other county to be moved to a wholly unitary system was Berkshire; the county council was abolished and 6 unitary authorities established in its place. In County Durham, North Yorkshire, Lancashire, Cheshire, Staffordshire, Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Cambridgeshire, Wiltshire, Hampshire, Devon, Dorset, East Sussex, Shropshire, Kent, Essex, Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire, one or two major towns/cities were established as unitary authorities, with the rest of the county remaining two tier. All other counties were unaffected.

Whilst these reforms had removed unpopular new counties, they created a rather haphazard situation, which was for the most part like the old counties & county borough system; but in which areas taken to make the abolished new counties was not returned to the historic county. Thus, for instance, the non-urban unitary authority of, e.g., Cleveland & Redcar was not, administratively, in any county. In recognition of these problems, the Lieutenancies Act 1997 was passed. This firmly separated all local authority areas (whether unitary or two-tier), from the geographical concept of a county as high level spatial unit. The lieutenancies it established became known as ceremonial counties, since they were no longer administrative divisions. The counties represent a compromise between the historic counties and the counties established in 1974. They are as 1974 except that; north Lincolnshire returned to Lincolnshire and the remainder of Humberside became East Riding of Yorkshire; Bristol is established as a county; the remainder of Avon returned to Somerset and Gloucestershire; Cleveland was split between County Durham and North Yorkshire; Herefordshire and Worcestershire were separated; and Rutland was re-established as a county.

Creation of additional unitary authorities after 2000

The years after 2000 saw further substantial changes, leading to a still more varied (some might say haphazard) system. Various counties were unitarised: some by abolition of districts (e.g. Cornwall, Northumberland), others by geographical division into two or more unitary authorities (e.g. Bedfordshire).

The Labour governments of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown (1997–2010) had planned to introduce eight regional assemblies around England, to devolve power to the English regions. This would have sat alongside the devolved Welsh, Scottish and Northern Irish Assemblies. In the event, only a London Assembly (and directly elected Mayor) was established. The rejection of a referendum on the creation of a North East England Assembly in 2004 led to those plans being scrapped.

Local enterprise partnerships and local authority leaders' boards

The abolition of regional development agencies and the creation of local enterprise partnerships were announced as part of the June 2010 United Kingdom budget. [30] On 29 June 2010 a letter was sent from the Department of Communities and Local Government and the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills to local authority and business leaders, inviting proposals to replace regional development agencies in their areas by 6 September 2010. [31]

Many of the regional development agencies were transferred to the unelected Local authority leaders' boards following abolition in March 2010, but funding was also cut for them by the Government in July 2010. These boards now act as voluntary regional associations for local authority leaders, funded by local authorities and its membership consisting of the leaders of local authorities.

On 7 September 2010, details were released of 56 proposals for local enterprise partnerships that had been received. [32] On 6 October 2010, during the Conservative Party Conference, it was revealed that 22 had been given the provisional 'green light' to proceed and others may later be accepted with amendments. [33] 24 bids were announced as successful on 28 October 2010. This later increased to 39, as of 2012.

Combined authorities

The abolition of metropolitan county councils and regional development agencies meant that there were no local government bodies with strategic authority over the major urban areas England. In 2010 the Government accepted a proposal from the Association of Greater Manchester Authorities to establish a Greater Manchester Combined Authority as an indirectly elected, top tier, strategic authority for Greater Manchester. Following the unsuccessful English mayoral referendums in 2012 combined authorities have been used as an alternative means to receive additional powers and funding as part of 'city deals' to metropolitan areas. In 2014 indirectly elected combined authorities were established for the metropolitan counties of South Yorkshire and West Yorkshire, and two combined authorities were established which each covered a metropolitan county and adjacent non-metropolitan districts: the Liverpool City Region Combined Authority for Merseyside and the Borough of Halton unitary authority, and the North East Combined Authority for Tyne and Wear and the unitary authorities of County Durham and Northumberland. Further combined authorities are proposed for a number of areas.

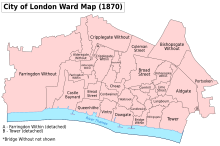

The City of London

The one exception to the general trends in the development of local government in England has been (and remains) the City of London. This refers only to the actual City of London (as distinct from the Greater London area, and the nearby City of Westminster). In the UK, city status is granted by royal charter; whilst in common parlance 'city' (lower case) is used to mean a large urban area, 'City' refers specifically to a specific legal entity. Thus, what might be considered the 'city of London' contains both the 'City of London' and 'City of Westminster'. The City of London, covering a relatively small area, (often called 'The Square Mile' or just 'The City') is the main financial district of London, and only houses c.7,200 permanent residents.

For a variety of reasons, including a singular relationship with the Crown, the City of London has remained an archaic oddity within the English system of local government. As discussed above, the City of London was administered separately from the reign of Alfred the Great onwards, and was very quickly granted self-governance after the Norman conquest. Until 1835, the City of London was a fairly normal (municipal) borough, run by the Lord Mayor and Corporation of London, which had also received county corporate status (and thus was technically 'The County and City of London'). However, unlike most other cities and boroughs of the time, London was not reformed by the Municipal Corporations Act 1835; and unlike the other unreformed cities and boroughs of the time, never has been.

In the major local government reforms of 1888 the City of London, unlike other municipal boroughs and counties corporate, was not made into either a county borough or a district within an administrative county. Nor indeed was it placed within a statutory county at that time, remaining administratively separate from the County of London (though within it geographically). Nor was the status of the City of London as a county corporate abolished in 1974, unlike the (by then ceremonial) status of the other counties corporate, nor was the City of London included in any of the London boroughs created in 1965; although at that time it did become included within the Greater London county, as a de facto 33rd borough in the second tier of local government. The City of London has continued in name and administration to be a municipal borough and county corporate since 1888, whilst acting as a de facto county borough until 1965, and since 1965 as a de facto London borough.

When Greater London Council was abolished in 1986, the City of London reverted to being a unitary authority (like the London boroughs). Under the terms of the Lieutenancies Act 1997, it is now classed as a ceremonial county by itself, separate from the Greater London ceremonial county (in to which the 32 London Boroughs are grouped). However, the City of London does now form part of the new Greater London region (which is the modern Greater London ceremonial county, plus the City of London; i.e., the post-1965 Greater London administrative area), and as such falls under the strategic management of the Greater London Authority.

The current system retains non-democratic elements to the election of the local government. The primary justification for this is that the services provided by the City of London are used by approximately 450,000 workers who dwell outside the City, and only by 7200 residents (a ratio not found elsewhere in the UK). In reflection of this, businesses based in the City can vote in the local elections, a practice abolished elsewhere in England in 1969. [34]

The City of London has a different type of ward to those used elsewhere in the country - another remnant of ancient local government found in the "square mile" of the City. The wards are permanent entities that constitute the City and are more than just electoral districts.

Table: The local government status of the City of London

| Division | pre-1835 | 1835 | 1888 | 1965 | 1986 | 1997 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Region (from 1997) |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | Greater London |

| Geographical County (including Statutory County (1888–1974)) |

Middlesex | Middlesex | County of London | Greater London | Greater London | Greater London |

|

Ceremonial County (from 1986) |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

Greater London de facto |

City of London de jure |

|

County Council (from 1888) |

n/a | n/a | none | Greater London | none (unitary authority) |

none (unitary authority) |

|

County Borough (from 1888–1974) |

n/a | n/a |

City of London (de facto) |

none | n/a | n/a |

|

District Council or Metropolitan Borough |

n/a | n/a | none |

City of London de facto |

City of London de facto unitary authority |

City of London de facto unitary authority |

|

Municipal Borough (theoretically obsolete from 1974) |

City of London | City of London | City of London | City of London | City of London | City of London |

|

County Corporate (theoretically obsolete from 1888) |

City of London | City of London | City of London | City of London | City of London | City of London |

Summary

| Date | Class | Division | Responsibility | Officials | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 700–1066 | First tier | Shire | Judiciary, militia (the Fyrd), maintenance of roads | Ealdorman, Shire-reeve ( Sheriff) | |

| Second tier | Hundred | Collective responsibility for behaviour | Hundred-man | ||

| 1066–1350 | First tier (de jure) |

County | Judiciary | Sheriff | |

| Second tier (de jure) |

Hundred | Theoretically responsible for maintenance of law and order | Effectively obsolete after Norman conquest | ||

| First tier (parallel, de facto) |

Fief | Actual control of population, raising of military forces | Baron, Duke, Earl, etc. | Land held "from The Crown" | |

| Second tier (parallel, de facto) |

Parish or manor |

Local administration | Sub-divisions of fiefs | ||

| Independent town | Borough | Administration of town | Mayor, Town Corporation | Granted by Charter from The Crown | |

| 1350–1540 | First tier | County County Corporate |

Judiciary, Keeping the peace | Sheriff, Justice of the Peace | County corporate status granted by The Crown |

| Second tier (unofficial) |

Parish | No official roles | |||

| Independent town | Borough | Administration of town | Mayor, Town Corporation | ||

| 1540–1832 | First tier | County County Corporate |

Judiciary, 'County business' (primarily through judiciary) | Sheriff, Justice of the Peace, Lord Lieutenant | |

| Second tier (non-governmental) |

Parish | Maintenance of roads (from 1555); administering the Poor Law (from 1605) | Vestry | Functions supervised by unpaid officials (e.g. Surveyor of Highways) | |

| Independent town | Borough | Administration of town | Mayor, Town Corporation | ||

| 1832–1888 | First tier | County County Corporate |

Sheriff, Justice of the Peace, Lord Lieutenant | ||

| Second tier (non-governmental) |

Parish | Maintenance of roads (until 1855); administration of the Poor Law (see below). | |||

| Second tier (non-governmental) |

Poor Law Unions from 1837 Sanitary districts from 1875 |

Administration of the Poor Law, public health and sanitation, | Poor Law Guardians, Town Corporations | Poor law unions formed by unions of parish councils; Rural sanitary districts formed from Poor law unions; Urban sanitary districts formed by municipal boroughs or Local Health Boards | |

| Independent town | Municipal Borough | Mayor, Town Corporation, elected councillors | Reformed from 1835 on | ||

| 1888–1974 (to 1965 in London) |

Super tier | Statutory county | Judiciary, Ceremonial | Sheriff, Justice of the Peace, Lord Lieutenant | Based on the historic counties of England |

| First tier |

Administrative county (incorporating counties corporate) |

County Councillor | Counties corporate retained their own ceremonial officials, but no other powers | ||

| First tier |

County boroughs (Towns with popn. over 50000) (incorporating counties corporate) |

Borough Councillor | |||

| Second tier |

Urban district (Called metropolitan boroughs in London) (Both) |

District Councillor | |||

| Second tier |

Rural district (Only in administrative counties) |

District Councillor | |||

| Second tier | Municipal Borough (Both) |

Administration of town business | Mayor, Town corporation | Effectively urban districts with a royal charter | |

| Third tier |

Civil parish (Rural districts only) |

Variable, generally 'upkeep of the town' | Parish Councillor | ||

| Sui generis | City of London | All local government functions | Lord Mayor of London | Technically a county corporate and municipal borough; effectively a county borough | |

| 1974–1997 | First tier | County (metropolitan or non-metropolitan) |

Sheriff, Justice of the Peace, Lord Lieutenant, County Councillor | Counties redrawn; generally based on historic counties | |

| Second tier | District or Metropolitan Borough |

District Councillor | |||

| Third tier | Civil Parish (rural areas only) |

Variable, generally 'upkeep of the town' | |||

| Sui generis | City of London | Lord Mayor of London | Technically a County Corporate and Municipal borough; effectively a London borough | ||

| 1997– | Super tier | Region | Strategic direction | Mayor of London (only London) | |

| Ceremonial |

Ceremonial county |

Ceremonial | Sheriff, Justice of the Peace, Lord Lieutenant | Compromise between counties of 1888 and 1974 | |

| First tier | (Administrative) County | County Councillor | |||

| Second tier | District | District Councillor | |||

| Joint tier |

Unitary Authority Metropolitan borough |

All local government administration | Councillor | ||

| Third tier | Civil Parish | Variable, generally 'upkeep of the town' | Parish Councillor | ||

| Sui generis | City of London | All local government administration | Lord Mayor of London | Technically a County Corporate and Municipal borough; effectively a unitary authority |

See also

References

- ^ W. Blackstone, COMMENTARIES ON THE LAWS OF ENGLAND 339, 343 (1541)

- ^ Carpenter, D. (2004) The Struggle for Mastery: Britain 1066-1284, Penguin history of Britain, London : Penguin, ISBN 0-14-014824-8 pp. 81, 84, 86.

- ^ The Royal Charter

- ^ Regulation of Forces Act 1871

- ^ Carl H. E. Zangerl, The Social Composition of the County Magistracy in England and Wales, 1831–1887, The Journal of British Studies, Vol. 11, No. 1. (November 1971), pp. 113–25.

- ^ An Act for the more easy assessing, collecting and levying of County Rates, ( 12 Geo. 2. c. 29)

- ^ Bridges Act 1803 ( 43 Geo. 3. c. 59) and Grand Jury (Ireland) Act 1833 ( 3 & 4 Will. 4. c. 78)

- ^ Blackstone (1765), p. 168.

- ^ May (1896), vol. I, p. 329.

- ^ Phillips and Wetherell (1995), p. 413.

- ^ Heater, Derek (2006). Citizenship in Britain: A History. Edinburgh University Press. p. 136. ISBN 9780748626724.

- ^ "Women's rights". The National Archives. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ "Which Act Gave Women the Right to Vote in Britain?". Synonym. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Johnston, Neil (1 March 2013), "Female Suffrage before 1918", The History of the Parliamentary Franchise, House of Commons Library, pp. 37–39, retrieved 16 March 2016

- ^ Cross, Charles (July 1973). "The Local Government Act 1972". Anglo-American Law Review. 2 (3): 351. doi: 10.1177/147377957300200305. S2CID 167576090.

- ^ Census data on population of Merthyr Tydfil

- ^ London Gazette, 1 May 1935

- ^ Report of the Royal Commission on the status of the County Borough of Merthyr Tydfil (Cmd.5039)

- ^ Thorpe, Andrew (1997). A History of the British Labour Party. London: Macmillan Education UK. pp. 125–126. doi: 10.1007/978-1-349-25305-0. ISBN 978-0-333-56081-5.

- ^ Local government in England and Wales during the period of reconstruction (Cmd.6579)

- ^ London Gazette, 26 October 1945

- ^ Report of the Local Government Boundary Commission for the year 1947

- ^ Local Government Act 1972 (c.70), s.216

- ^ Elcock, H., Local Government, (1994)

- ^ Her Majesty's Stationery Office, Aspects of Britain: Local Government, (1996)

- ^ Angry reaction to councils White Paper. The Times. 8 October 1983.

- ^ politics.co.uk Issue Brief Archived 13 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine and Jonathan Rawle's website refer.

- ^ Redcliffe-Maud, Lord (1974). English Local Government Reformed. Wood, Bruce. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-888091-X.

- ^ Wood, Bruce (1976). The Process of Local Government Reform: 1966-1974. George Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-04-350052-8.

- ^ Mark Hoban (22 June 2010). Budget 2010 (PDF). HM Treasury. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ "Local enterprise partnerships". Department of Communities and Local Government. 29 June 2010. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

-

^ Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (7 September 2010).

"New Local Enterprise Partnerships criss-cross the country". News Distribution Service. Archived from

the original on 13 September 2010. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

{{ cite news}}:|author=has generic name ( help) - ^ Allister Hayman (6 October 2010). "LEPs: 22 bald men fighting over a comb?". Local Government Chronicle. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ "Elections: City of London". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Lords. 25 May 2006. col. 91WS–92WS.