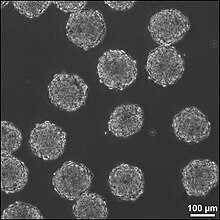

Embryoid bodies (EBs) are three-dimensional aggregates formed by pluripotent stem cells. These include embryonic stem cells (ESC) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC)

EBs are differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into embryoid bodies comprising the three embryonic germ layers. They mimic the characteristics seen in early-stage embryos. They are often used as a model system to conduct research on various aspects of developmental biology. They can also contribute to research focused on tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

Background

The pluripotent cell types that comprise embryoid bodies include embryonic stem cells (ESCs) derived from the blastocyst stage of embryos from mouse (mESC), [1] [2] primate, [3] and human (hESC) [4] sources. Additionally, EBs can be formed from embryonic stem cells derived through alternative techniques, including somatic cell nuclear transfer [5] [6] [7] or the reprogramming of somatic cells to yield induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS). [8] [9] [10] [11] Similar to ESCs cultured in monolayer formats, ESCs within embryoid bodies undergo differentiation and cell specification along the three germ lineages – endoderm, ectoderm, and mesoderm – which comprise all somatic cell types. [12] [13]

In contrast to monolayer cultures, however, the spheroid structures that are formed when ESCs aggregate enables the non-adherent culture of EBs in suspension, making EB cultures inherently scalable, which is useful for bioprocessing approaches, whereby large yields of cells can be produced for potential clinical applications. [14] Additionally, although EBs largely exhibit heterogeneous patterns of differentiated cell types, ESCs are capable of responding to similar cues that direct embryonic development. [15] Therefore, the three-dimensional structure, including the establishment of complex cell adhesions and paracrine signaling within the EB microenvironment, [16] enables differentiation and morphogenesis which yields microtissues that are similar to native tissue structures. Such microtissues are promising to directly [15] or indirectly [17] [18] repair damaged or diseased tissue in regenerative medicine applications, as well as for in vitro testing in the pharmaceutical industry and as a model of embryonic development.

Formation

EBs are formed by the homophilic binding of the Ca2+ dependent adhesion molecule E-cadherin, which is highly expressed on undifferentiated ESCs. [19] [20] [21] When cultured as single cells in the absence of anti-differentiation factors, ESCs spontaneously aggregate to form EBs. [19] [22] [23] [24] Such spontaneous formation is often accomplished in bulk suspension cultures whereby the dish is coated with non-adhesive materials, such as agar or hydrophilic polymers, to promote the preferential adhesion between single cells, rather than to the culture substrate. As hESC undergo apoptosis when cultured as single cells, EB formation often necessitates the use of inhibitors of the rho associated kinase (ROCK) pathway, including the small molecules Y-27632 [25] and 2,4 disubstituted thiazole (Thiazovivin/Tzv). [26] Alternatively, to avoid dissociation into single cells, EBs can be formed from hESCs by manual separation of adherent colonies (or regions of colonies) and subsequently cultured in suspension. Formation of EBs in suspension is amenable to the formation of large quantities of EBs, but provides little control over the size of the resulting aggregates, often leading to large, irregularly shaped EBs. As an alternative, the hydrodynamic forces imparted in mixed culture platforms increase the homogeneity of EB sizes when ESCs are inoculated within bulk suspensions. [27]

Formation of EBs can also be more precisely controlled by the inoculation of known cell densities within single drops (10-20 µL) suspended from the lid of a Petri dish, known as hanging drops. [21] While this method enables control of EB size by altering the number of cells per drop, the formation of hanging drops is labor-intensive and not easily amenable to scalable cultures. Additionally, the media can not be easily exchanged within the traditional hanging drop format, necessitating the transfer of hanging drops into bulk suspension cultures after 2–3 days of formation, whereby individual EBs tend to agglomerate. Recently, new technologies have been developed to enable media exchange within a modified hanging drop format. [28] In addition, technologies have also been developed to physically separate cells by forced aggregation of ESCs within individual wells or confined on adhesive substrates, [29] [30] [31] [32] which enables increased throughput, controlled formation of EBs. Ultimately, the methods used for EB formation may impact the heterogeneity of EB populations, in terms of aggregation kinetics, EB size and yield, as well as differentiation trajectories. [31] [33] [34]

Differentiation within EBs

Within the context of ESC differentiation protocols, EB formation is often used as a method for initiating spontaneous differentiation toward the three germ lineages. EB differentiation begins with the specification of the exterior cells toward the primitive endoderm phenotype. [35] [36] The cells at the exterior then deposit extracellular matrix (ECM), containing collagen IV and laminin, [37] [38] similar to the composition and structure of basement membrane. In response to the ECM deposition, EBs often form a cystic cavity, whereby the cells in contact with the basement membrane remain viable and those at the interior undergo apoptosis, resulting in a fluid-filled cavity surrounded by cells. [39] [40] [41] Subsequent differentiation proceeds to form derivatives of the three germ lineages. In the absence of supplements, the “default” differentiation of ESCs is largely toward ectoderm, and subsequent neural lineages. [42] However, alternative media compositions, including the use of fetal bovine serum as well as defined growth factor additives, have been developed to promote the differentiation toward mesoderm and endoderm lineages. [43] [44] [45]

As a result of the three-dimensional EB structure, complex morphogenesis occurs during EB differentiation, including the appearance of both epithelial- and mesenchymal-like cell populations, as well as the appearance of markers associated with the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). [46] [47] Additionally, the inductive effects resulting from signaling between cell populations in EBs results in spatially and temporally defined changes, which promote complex morphogenesis. [48] Tissue-like structures are often exhibited within EBs, including the appearance of blood islands reminiscent of early blood vessel structures in the developing embryo, as well as the patterning of neurite extensions (indicative of neuron organization) and spontaneous contractile activity (indicative of cardiomyocyte differentiation) when EBs are plated onto adhesive substrates such as gelatin. [13] More recently, complex structures, including optic cup-like structures were created in vitro resulting from EB differentiation. [49]

Parallels with embryonic development

Much of the research central to embryonic stem cell differentiation and morphogenesis is derived from studies in developmental biology and mammalian embryogenesis. [15] For example, immediately after the blastocyst stage of development (from which ESCs are derived), the embryo undergoes differentiation, whereby cell specification of the inner cell mass results in the formation of the hypoblast and epiblast. [50] Later on in postimplantation development, the anterior-posterior axis is formed and the embryo develops a transient structure known as the primitive streak. [51] Much of the spatial patterning that occurs during the formation and migration of the primitive streak results from the secretion of agonists and antagonists by various cell populations, including the growth factors from the Wnt and transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) families (Lefty 1, Nodal), as well as repressors of the same molecules (Dkk-1, Sfrp1, Sfrp5). [52] [53] [54] Due to the similarities between embryogenesis and ESC differentiation, many of the same growth factors are central to directed differentiation approaches.

In addition, advancements of EB culture resulted in the development of embryonic organoids (Gastruloids) which show remarkable parallels to embryonic development [46] [55] [56] [57] [58] [59] such as symmetry-breaking, localised brachyury expression, the formation of the embryonic axes (anteroposterior, dorsoventral and Left-Right) and gastrulation-like movements. [46] [55] [56] [57]

Challenges to directing differentiation

In contrast to the differentiation of ESCs in monolayer cultures, whereby the addition of soluble morphogens and the extracellular microenvironment can be precisely and homogeneously controlled, the three-dimensional structure of EBs poses challenges to directed differentiation. [16] [60] For example, the visceral endoderm population which forms the exterior of EBs, creates an exterior “shell” consisting of tightly connected epithelial-like cells, as well as a dense ECM. [61] [62] Due to such physical restrictions, in combination with EB size, transport limitations occur within EBs, creating gradients of morphogens, metabolites, and nutrients. [60] It has been estimated that oxygen transport is limited in cell aggregates larger than approximately 300 µm in diameter; [63] however, the development of such gradients are also impacted by molecule size and cell uptake rates. Therefore, the delivery of morphogens to EBs results in increased heterogeneity and decreased efficiency of differentiated cell populations compared to monolayer cultures. One method of addressing transport limitations within EBs has been through polymeric delivery of morphogens from within the EB structure. [61] [64] [65] Additionally, EBs can be cultured as individual microtissues and subsequently assembled into larger structures for tissue engineering applications. [66] Although the complexity resulting from the three-dimensional adhesions and signaling may recapitulate more native tissue structures, [67] [68] it also creates challenges for understanding the relative contributions of mechanical, chemical, and physical signals to the resulting cell phenotypes and morphogenesis.

See also

References

- ^ Martin, G. R. (1981). "Isolation of a pluripotent cell line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem cells". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 78 (12): 7634–7638. Bibcode: 1981PNAS...78.7634M. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7634. PMC 349323. PMID 6950406.

- ^ Evans, M. J.; Kaufman, M. H. (1981). "Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos". Nature. 292 (5819): 154–156. Bibcode: 1981Natur.292..154E. doi: 10.1038/292154a0. PMID 7242681. S2CID 4256553.

- ^ Thomson, J. A.; Kalishman, J.; Golos, T. G.; Durning, M.; Harris, C. P.; Becker, R. A.; Hearn, J. P. (1995). "Isolation of a primate embryonic stem cell line". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 92 (17): 7844–7848. Bibcode: 1995PNAS...92.7844T. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7844. PMC 41242. PMID 7544005.

- ^ Thomson, J. A.; Itskovitz-Eldor, J.; Shapiro, S. S.; Waknitz, M. A.; Swiergiel, J. J.; Marshall, V. S.; Jones, J. M. (1998). "Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts". Science. 282 (5391): 1145–1147. Bibcode: 1998Sci...282.1145T. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. PMID 9804556.

- ^ Briggs, R.; King, T. J. (1952). "Transplantation of Living Nuclei from Blastula Cells into Enucleated Frogs' Eggs". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 38 (5): 455–463. Bibcode: 1952PNAS...38..455B. doi: 10.1073/pnas.38.5.455. PMC 1063586. PMID 16589125.

- ^ Wilmut, I.; Schnieke, A. E.; McWhir, J.; Kind, A. J.; Campbell, K. H. S. (1997). "Viable offspring derived from fetal and adult mammalian cells". Nature. 385 (6619): 810–813. Bibcode: 1997Natur.385..810W. doi: 10.1038/385810a0. PMID 9039911. S2CID 4260518.

- ^ Munsie, M. J.; Michalska, A. E.; O'Brien, C. M.; Trounson, A. O.; Pera, M. F.; Mountford, P. S. (2000). "Isolation of pluripotent embryonic stem cells from reprogrammed adult mouse somatic cell nuclei". Current Biology. 10 (16): 989–992. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00648-5. PMID 10985386.

- ^ Takahashi, K.; Yamanaka, S. (2006). "Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Mouse Embryonic and Adult Fibroblast Cultures by Defined Factors". Cell. 126 (4): 663–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. hdl: 2433/159777. PMID 16904174. S2CID 1565219.

- ^ Takahashi, K.; Tanabe, K.; Ohnuki, M.; Narita, M.; Ichisaka, T.; Tomoda, K.; Yamanaka, S. (2007). "Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Adult Human Fibroblasts by Defined Factors". Cell. 131 (5): 861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. hdl: 2433/49782. PMID 18035408. S2CID 8531539.

- ^ Yu, J.; Vodyanik, M. A.; Smuga-Otto, K.; Antosiewicz-Bourget, J.; Frane, J. L.; Tian, S.; Nie, J.; Jonsdottir, G. A.; Ruotti, V.; Stewart, R.; Slukvin, I. I.; Thomson, J. A. (2007). "Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Lines Derived from Human Somatic Cells". Science. 318 (5858): 1917–1920. Bibcode: 2007Sci...318.1917Y. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. PMID 18029452. S2CID 86129154.

- ^ Park, I. H.; Arora, N.; Huo, H.; Maherali, N.; Ahfeldt, T.; Shimamura, A.; Lensch, M. W.; Cowan, C.; Hochedlinger, K.; Daley, G. Q. (2008). "Disease-Specific Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells". Cell. 134 (5): 877–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.041. PMC 2633781. PMID 18691744.

- ^ Itskovitz-Eldor, J.; Schuldiner, M.; Karsenti, D.; Eden, A.; Yanuka, O.; Amit, M.; Soreq, H.; Benvenisty, N. (2000). "Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into embryoid bodies compromising the three embryonic germ layers". Molecular Medicine. 6 (2): 88–95. doi: 10.1007/BF03401776. PMC 1949933. PMID 10859025.

- ^ a b Doetschman, T. C.; Eistetter, H.; Katz, M.; Schmidt, W.; Kemler, R. (1985). "The in vitro development of blastocyst-derived embryonic stem cell lines: Formation of visceral yolk sac, blood islands and myocardium". Journal of Embryology and Experimental Morphology. 87: 27–45. PMID 3897439.

- ^ Dang, S. M.; Gerecht-Nir, S.; Chen, J.; Itskovitz-Eldor, J.; Zandstra, P. W. (2004). "Controlled, Scalable Embryonic Stem Cell Differentiation Culture". Stem Cells. 22 (3): 275–282. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-3-275. PMID 15153605.

- ^ a b c Murry, C. E.; Keller, G. (2008). "Differentiation of Embryonic Stem Cells to Clinically Relevant Populations: Lessons from Embryonic Development". Cell. 132 (4): 661–680. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.008. PMID 18295582.

- ^ a b Bratt-Leal, A. S. M.; Carpenedo, R. L.; McDevitt, T. C. (2009). "Engineering the embryoid body microenvironment to direct embryonic stem cell differentiation". Biotechnology Progress. 25 (1): 43–51. doi: 10.1002/btpr.139. PMC 2693014. PMID 19198003.

- ^ Nair, R.; Shukla, S.; McDevitt, T. C. (2008). "Acellular matrices derived from differentiating embryonic stem cells". Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 87A (4): 1075–1085. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31851. hdl: 1853/37170. PMID 18260134.

- ^ Baraniak, P. R.; McDevitt, T. C. (2010). "Stem cell paracrine actions and tissue regeneration". Regenerative Medicine. 5 (1): 121–143. doi: 10.2217/rme.09.74. PMC 2833273. PMID 20017699.

- ^ a b Kurosawa, H. (2007). "Methods for inducing embryoid body formation: In vitro differentiation system of embryonic stem cells". Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering. 103 (5): 389–398. doi: 10.1263/jbb.103.389. PMID 17609152.

- ^ Larue, L.; Antos, C.; Butz, S.; Huber, O.; Delmas, V.; Dominis, M.; Kemler, R. (1996). "A role for cadherins in tissue formation". Development. 122 (10): 3185–3194. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3185. PMID 8898231.

- ^ a b Yoon, B. S.; Yoo, S. J.; Lee, J. E.; You, S.; Lee, H. T.; Yoon, H. S. (2006). "Enhanced differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into cardiomyocytes by combining hanging drop culture and 5-azacytidine treatment". Differentiation. 74 (4): 149–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2006.00063.x. PMID 16683985.

- ^ Park, J. H.; Kim, S. J.; Oh, E. J.; Moon, S. Y.; Roh, S. I.; Kim, C. G.; Yoon, H. S. (2003). "Establishment and Maintenance of Human Embryonic Stem Cells on STO, a Permanently Growing Cell Line". Biology of Reproduction. 69 (6): 2007–2014. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.017467. PMID 12930726.

- ^ Williams, R. L.; Hilton, D. J.; Pease, S.; Willson, T. A.; Stewart, C. L.; Gearing, D. P.; Wagner, E. F.; Metcalf, D.; Nicola, N. A.; Gough, N. M. (1988). "Myeloid leukaemia inhibitory factor maintains the developmental potential of embryonic stem cells". Nature. 336 (6200): 684–687. Bibcode: 1988Natur.336..684W. doi: 10.1038/336684a0. PMID 3143916. S2CID 4346252.

- ^ Ludwig, T. E.; Levenstein, M. E.; Jones, J. M.; Berggren, W. T.; Mitchen, E. R.; Frane, J. L.; Crandall, L. J.; Daigh, C. A.; Conard, K. R.; Piekarczyk, M. S.; Llanas, R. A.; Thomson, J. A. (2006). "Derivation of human embryonic stem cells in defined conditions". Nature Biotechnology. 24 (2): 185–187. doi: 10.1038/nbt1177. PMID 16388305. S2CID 11484871.

- ^ Watanabe, K.; Ueno, M.; Kamiya, D.; Nishiyama, A.; Matsumura, M.; Wataya, T.; Takahashi, J. B.; Nishikawa, S.; Nishikawa, S. I.; Muguruma, K.; Sasai, Y. (2007). "A ROCK inhibitor permits survival of dissociated human embryonic stem cells". Nature Biotechnology. 25 (6): 681–686. doi: 10.1038/nbt1310. PMID 17529971. S2CID 8213725.

- ^ Xu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Hahm, H. S.; Wei, W.; Hao, E.; Hayek, A.; Ding, S. (2010). "Revealing a core signaling regulatory mechanism for pluripotent stem cell survival and self-renewal by small molecules". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (18): 8129–8134. Bibcode: 2010PNAS..107.8129X. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002024107. PMC 2889586. PMID 20406903.

- ^ Carpenedo, R. L.; Sargent, C. Y.; McDevitt, T. C. (2007). "Rotary Suspension Culture Enhances the Efficiency, Yield, and Homogeneity of Embryoid Body Differentiation". Stem Cells. 25 (9): 2224–2234. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0523. PMID 17585171. S2CID 25461651.

- ^ Tung, Y. C.; Hsiao, A. Y.; Allen, S. G.; Torisawa, Y. S.; Ho, M.; Takayama, S. (2011). "High-throughput 3D spheroid culture and drug testing using a 384 hanging drop array". The Analyst. 136 (3): 473–478. Bibcode: 2011Ana...136..473T. doi: 10.1039/c0an00609b. PMC 7454010. PMID 20967331. S2CID 35415772.

- ^ Park, J.; Cho, C. H.; Parashurama, N.; Li, Y.; Berthiaume, F. O.; Toner, M.; Tilles, A. W.; Yarmush, M. L. (2007). "Microfabrication-based modulation of embryonic stem cell differentiation". Lab on a Chip. 7 (8): 1018–1028. doi: 10.1039/b704739h. PMID 17653344.

- ^ Mohr, J. C.; De Pablo, J. J.; Palecek, S. P. (2006). "3-D microwell culture of human embryonic stem cells". Biomaterials. 27 (36): 6032–6042. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.07.012. PMID 16884768.

- ^ a b Hwang, Y. -S.; Chung, B. G.; Ortmann, D.; Hattori, N.; Moeller, H. -C.; Khademhosseini, A. (2009). "Microwell-mediated control of embryoid body size regulates embryonic stem cell fate via differential expression of WNT5a and WNT11". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (40): 16978–16983. Bibcode: 2009PNAS..10616978H. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905550106. PMC 2761314. PMID 19805103.

- ^ Ungrin, M. D.; Joshi, C.; Nica, A.; Bauwens, C. L.; Zandstra, P. W. (2008). Callaerts, Patrick (ed.). "Reproducible, Ultra High-Throughput Formation of Multicellular Organization from Single Cell Suspension-Derived Human Embryonic Stem Cell Aggregates". PLOS ONE. 3 (2): e1565. Bibcode: 2008PLoSO...3.1565U. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001565. PMC 2215775. PMID 18270562.

- ^ Sargent, C. Y.; Berguig, G. Y.; McDevitt, T. C. (2009). "Cardiomyogenic Differentiation of Embryoid Bodies is Promoted by Rotary Orbital Suspension Culture". Tissue Engineering Part A. 15 (2): 331–342. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0145. PMID 19193130.

- ^ Bauwens, C. L. L.; Peerani, R.; Niebruegge, S.; Woodhouse, K. A.; Kumacheva, E.; Husain, M.; Zandstra, P. W. (2008). "Control of Human Embryonic Stem Cell Colony and Aggregate Size Heterogeneity Influences Differentiation Trajectories". Stem Cells. 26 (9): 2300–2310. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0183. PMID 18583540.

- ^ Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Eswarakumar, V. P.; Seger, R.; Lonai, P. (2000). "Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling through PI 3-kinase and Akt/PKB is required for embryoid body differentiation". Oncogene. 19 (33): 3750–3756. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203726. PMID 10949929.

- ^ Esner, M.; Pachernik, J.; Hampl, A.; Dvorak, P. (2002). "Targeted disruption of fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 blocks maturation of visceral endoderm and cavitation in mouse embryoid bodies". The International Journal of Developmental Biology. 46 (6): 817–825. PMID 12382948.

- ^ Wan, Y. J.; Wu, T. C.; Chung, A. E.; Damjanov, I. (1984). "Monoclonal antibodies to laminin reveal the heterogeneity of basement membranes in the developing and adult mouse tissues". The Journal of Cell Biology. 98 (3): 971–979. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.3.971. PMC 2113154. PMID 6365932.

- ^ Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Schéele, S.; Arman, E.; Haffner-Krausz, R.; Ekblom, P.; Lonai, P. (2001). "Fibroblast growth factor signaling and basement membrane assembly are connected during epithelial morphogenesis of the embryoid body". The Journal of Cell Biology. 153 (4): 811–822. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.4.811. PMC 2192393. PMID 11352941.

- ^ Coucouvanis, E.; Martin, G. R. (1995). "Signals for death and survival: A two-step mechanism for cavitation in the vertebrate embryo". Cell. 83 (2): 279–287. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90169-8. PMID 7585945.

- ^ Smyth, N.; Vatansever, H. S.; Murray, P.; Meyer, M.; Frie, C.; Paulsson, M.; Edgar, D. (1999). "Absence of basement membranes after targeting the LAMC1 gene results in embryonic lethality due to failure of endoderm differentiation". The Journal of Cell Biology. 144 (1): 151–160. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.1.151. PMC 2148127. PMID 9885251.

- ^ Murray, P.; Edgar, D. (2000). "Regulation of programmed cell death by basement membranes in embryonic development". The Journal of Cell Biology. 150 (5): 1215–1221. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.5.1215. PMC 2175256. PMID 10974008.

- ^ Ying, Q. L.; Smith, A. G. (2003). "Defined Conditions for Neural Commitment and Differentiation". Differentiation of Embryonic Stem Cells. Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 365. pp. 327–341. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(03)65023-8. ISBN 9780121822682. PMID 14696356.

- ^ Wiles, M. V.; Keller, G. (1991). "Multiple hematopoietic lineages develop from embryonic stem (ES) cells in culture". Development. 111 (2): 259–267. doi: 10.1242/dev.111.2.259. PMID 1893864.

- ^ Purpura, K. A.; Morin, J.; Zandstra, P. W. (2008). "Analysis of the temporal and concentration-dependent effects of BMP-4, VEGF, and TPO on development of embryonic stem cell–derived mesoderm and blood progenitors in a defined, serum-free media". Experimental Hematology. 36 (9): 1186–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.04.003. PMID 18550259.

- ^ Nostro, M. C.; Cheng, X.; Keller, G. M.; Gadue, P. (2008). "Wnt, Activin, and BMP Signaling Regulate Distinct Stages in the Developmental Pathway from Embryonic Stem Cells to Blood". Cell Stem Cell. 2 (1): 60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.011. PMC 2533280. PMID 18371422.

- ^ a b c Ten Berge, D.; Koole, W.; Fuerer, C.; Fish, M.; Eroglu, E.; Nusse, R. (2008). "Wnt Signaling Mediates Self-Organization and Axis Formation in Embryoid Bodies". Cell Stem Cell. 3 (5): 508–518. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.09.013. PMC 2683270. PMID 18983966.

- ^ Shukla, S.; Nair, R.; Rolle, M. W.; Braun, K. R.; Chan, C. K.; Johnson, P. Y.; Wight, T. N.; McDevitt, T. C. (2009). "Synthesis and Organization of Hyaluronan and Versican by Embryonic Stem Cells Undergoing Embryoid Body Differentiation". Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 58 (4): 345–358. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2009.954826. PMC 2842597. PMID 20026669.

- ^ Bauwens, C. L.; Song, H.; Thavandiran, N.; Ungrin, M.; Massé, S. P.; Nanthakumar, K.; Seguin, C.; Zandstra, P. W. (2011). "Geometric Control of Cardiomyogenic Induction in Human Pluripotent Stem Cells". Tissue Engineering Part A. 17 (15–16): 1901–1909. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2010.0563. hdl: 1807/33799. PMID 21417693. S2CID 22010083.

- ^ Eiraku, M.; Takata, N.; Ishibashi, H.; Kawada, M.; Sakakura, E.; Okuda, S.; Sekiguchi, K.; Adachi, T.; Sasai, Y. (2011). "Self-organizing optic-cup morphogenesis in three-dimensional culture". Nature. 472 (7341): 51–56. Bibcode: 2011Natur.472...51E. doi: 10.1038/nature09941. PMID 21475194. S2CID 4421136.

- ^ Bielinska, M.; Narita, N.; Wilson, D. B. (1999). "Distinct roles for visceral endoderm during embryonic mouse development". The International Journal of Developmental Biology. 43 (3): 183–205. PMID 10410899.

- ^ Burdsal, C. A.; Damsky, C. H.; Pedersen, R. A. (1993). "The role of E-cadherin and integrins in mesoderm differentiation and migration at the mammalian primitive streak". Development. 118 (3): 829–844. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.3.829. PMID 7521282.

- ^ Finley, K. R.; Tennessen, J.; Shawlot, W. (2003). "The mouse secreted frizzled-related protein 5 gene is expressed in the anterior visceral endoderm and foregut endoderm during early post-implantation development". Gene Expression Patterns. 3 (5): 681–684. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(03)00091-7. PMID 12972006.

- ^ Kemp, C.; Willems, E.; Abdo, S.; Lambiv, L.; Leyns, L. (2005). "Expression of all Wnt genes and their secreted antagonists during mouse blastocyst and postimplantation development". Developmental Dynamics. 233 (3): 1064–1075. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20408. PMID 15880404. S2CID 20596850.

- ^ Rivera-Pérez, J. A.; Magnuson, T. (2005). "Primitive streak formation in mice is preceded by localized activation of Brachyury and Wnt3". Developmental Biology. 288 (2): 363–371. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.09.012. PMID 16289026.

- ^ a b Turner, David; Alonso-Crisostomo, Luz; Girgin, Mehmet; Baillie-Johnson, Peter; Glodowski, Cherise R.; Hayward, Penelope C.; Collignon, Jérôme; Gustavsen, Carsten; Serup, Palle (2017-01-31). "Gastruloids develop the three body axes in the absence of extraembryonic tissues and spatially localised signalling". bioRxiv 10.1101/104539.

- ^ a b Turner, David Andrew; Glodowski, Cherise R.; Luz, Alonso-Crisostomo; Baillie-Johnson, Peter; Hayward, Penny C.; Collignon, Jérôme; Gustavsen, Carsten; Serup, Palle; Schröter, Christian (2016-05-13). "Interactions between Nodal and Wnt signalling Drive Robust Symmetry Breaking and Axial Organisation in Gastruloids (Embryonic Organoids)". bioRxiv 10.1101/051722.

- ^ a b Baillie-Johnson, Peter; Brink, Susanne Carina van den; Balayo, Tina; Turner, David Andrew; Arias, Alfonso Martinez (2015-11-24). "Generation of Aggregates of Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells that Show Symmetry Breaking, Polarization and Emergent Collective Behaviour In Vitro". Journal of Visualized Experiments (105): e53252. doi: 10.3791/53252. ISSN 1940-087X. PMC 4692741. PMID 26650833.

- ^ Brink, Susanne C. van den; Baillie-Johnson, Peter; Balayo, Tina; Hadjantonakis, Anna-Katerina; Nowotschin, Sonja; Turner, David A.; Arias, Alfonso Martinez (2014-11-15). "Symmetry breaking, germ layer specification and axial organisation in aggregates of mouse embryonic stem cells". Development. 141 (22): 4231–4242. doi: 10.1242/dev.113001. ISSN 0950-1991. PMC 4302915. PMID 25371360.

- ^ Turner, David A.; Hayward, Penelope C.; Baillie-Johnson, Peter; Rué, Pau; Broome, Rebecca; Faunes, Fernando; Arias, Alfonso Martinez (2014-11-15). "Wnt/β-catenin and FGF signalling direct the specification and maintenance of a neuromesodermal axial progenitor in ensembles of mouse embryonic stem cells". Development. 141 (22): 4243–4253. doi: 10.1242/dev.112979. ISSN 0950-1991. PMC 4302903. PMID 25371361.

- ^ a b Kinney, M. A.; Sargent, C. Y.; McDevitt, T. C. (2011). "The Multiparametric Effects of Hydrodynamic Environments on Stem Cell Culture". Tissue Engineering Part B: Reviews. 17 (4): 249–262. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEB.2011.0040. PMC 3142632. PMID 21491967.

- ^ a b Carpenedo, R. L.; Bratt-Leal, A. S. M.; Marklein, R. A.; Seaman, S. A.; Bowen, N. J.; McDonald, J. F.; McDevitt, T. C. (2009). "Homogeneous and organized differentiation within embryoid bodies induced by microsphere-mediated delivery of small molecules". Biomaterials. 30 (13): 2507–2515. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.01.007. PMC 2921510. PMID 19162317.

- ^ Sachlos, E.; Auguste, D. T. (2008). "Embryoid body morphology influences diffusive transport of inductive biochemicals: A strategy for stem cell differentiation". Biomaterials. 29 (34): 4471–4480. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.08.012. PMID 18793799.

- ^ Van Winkle, A. P.; Gates, I. D.; Kallos, M. S. (2012). "Mass Transfer Limitations in Embryoid Bodies during Human Embryonic Stem Cell Differentiation". Cells Tissues Organs. 196 (1): 34–47. doi: 10.1159/000330691. PMID 22249133. S2CID 42754482.

- ^ Bratt-Leal, A. S. M.; Carpenedo, R. L.; Ungrin, M. D.; Zandstra, P. W.; McDevitt, T. C. (2011). "Incorporation of biomaterials in multicellular aggregates modulates pluripotent stem cell differentiation". Biomaterials. 32 (1): 48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.113. PMC 2987521. PMID 20864164.

- ^ Purpura, K. A.; Bratt-Leal, A. S. M.; Hammersmith, K. A.; McDevitt, T. C.; Zandstra, P. W. (2012). "Systematic engineering of 3D pluripotent stem cell niches to guide blood development". Biomaterials. 33 (5): 1271–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.10.051. PMC 4280365. PMID 22079776.

- ^ Bratt-Leal, A. S. M.; Kepple, K. L.; Carpenedo, R. L.; Cooke, M. T.; McDevitt, T. C. (2011). "Magnetic manipulation and spatial patterning of multi-cellular stem cell aggregates". Integrative Biology. 3 (12): 1224–1232. doi: 10.1039/c1ib00064k. PMC 4633527. PMID 22076329.

- ^ Akins, R. E.; Rockwood, D.; Robinson, K. G.; Sandusky, D.; Rabolt, J.; Pizarro, C. (2010). "Three-Dimensional Culture Alters Primary Cardiac Cell Phenotype". Tissue Engineering Part A. 16 (2): 629–641. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0458. PMC 2813151. PMID 20001738.

- ^ Chang, T. T.; Hughes-Fulford, M. (2009). "Monolayer and Spheroid Culture of Human Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cell Line Cells Demonstrate Distinct Global Gene Expression Patterns and Functional Phenotypes". Tissue Engineering Part A. 15 (3): 559–567. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0434. PMC 6468949. PMID 18724832.