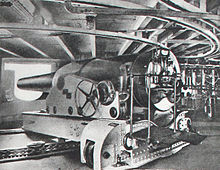

The central battery ship, also known as a centre battery ship in the United Kingdom and as a casemate ship in European continental navies, was a development of the (high- freeboard) broadside ironclad of the 1860s, given a substantial boost due to the inspiration gained from the Battle of Hampton Roads, the first battle between ironclads fought in 1862 during the American Civil War. One of the participants was the Confederate casemate ironclad CSS Virginia, essentially a central battery ship herself, albeit a low-freeboard one. The central battery ships had their main guns concentrated in the middle of the ship in an armoured citadel. [1] The concentration of armament amidships meant the ship could be shorter and handier than a broadside type like previous warships. In this manner the design could maximize the thickness of armour in a limited area while still carrying a significant broadside. These ships meant the end of the armoured frigates with their full-length gun decks.

In the UK, the man behind the design was the newly appointed Chief Constructor of the Royal Navy, Edward James Reed. The previous Royal Navy ironclad designs, represented by HMS Warrior, had proven to be seaworthy, fast under power and sail, but their armour could be easily penetrated by more modern guns. The first central battery ship was HMS Bellerophon of 1865. Great Britain built a total of 18 central battery ships before turrets became common on high-freeboard ships in the 1880s. [2]

The second British central battery ship, HMS Hercules, served as model for the Austrian navy, starting with their first design SMS Lissa (6,100 tons) designed by Josef von Romako and launched in 1871. The Austrian SMS Kaiser—not to be confused with German Kaiser—was built along a similar design, although the hull had been converted from a wooden ship, and it was slightly smaller (5,800 tons). The Austrian central battery design was pushed further with SMS Custoza (7,100 tons) and SMS Erzherzog Albrecht (5,900 tons), which had double-decked casemates; after studying the Battle of Lissa, Romako designed these so more guns could shoot forward. Three older broadside ironclads of the Kaiser Max class (3600 tons: Kaiser Max, Don Juan D'Austria and Prinz Eugen) were also officially "converted" to casemate design, although they were mostly built from scratch. The largest design yet was Tegetthoff, later renamed to Mars when the new dreadnought battleship Tegetthoff was commissioned. [2] [3] The Austrian records distinguish between the category of older broadside ironclads and the newer designs using the words Panzerfregatten (armoured frigates) and respectively Casemattschiffe (casemate ships). [4] [5]

The Imperial Russian Navy had built one central battery ironclad, Kniaz Pozharsky ( Russian: Князь Пожарский), in 1864. It carried eight Obukhov 9-inch (229 mm) breech-loading guns, and was the first Russian armoured ship to venture out to the Pacific.

The German navy had two large casemate ships (about 8800 tons) of the Kaiser class built in UK shipyards. [6] The first ironclad of the Greek navy, Vasilefs Georgios (1867), was also built in the UK; at 1700 tons, it was a minimalist casemate design having only two large 9in guns, and two small 20-pounders. The Italians had three casemate ships built, Venezia, converted from broadside during construction, and the two Principe Amedeo-class ironclads. [7] Chile also bought two from the United Kingdom: Blanco Encalada and Almirante Cochrane.

The disadvantage of the centre-battery was that, while more flexible than the broadside, each gun still had a relatively restricted field of fire and few guns could fire directly ahead. The centre-battery ships were soon succeeded by turreted warships.

See also

Notes

- ^ Sondhaus (1994), p. 44.

- ^ a b Sondhaus (1994), pp. 44–47.

- ^ Gardiner (1979), pp. 269–270.

- ^ Statistisches Jahrbuch der Oesterreichischen Monarchie. K. K. Statistische Central-Commission. 1875. pp. 74–75.

- ^ von Zvolenszky, Alfred (1887). Handbuch über die k. k. Kriegs-Marine. A. Hartleben's Verlag. p. 13.

- ^ Gardiner (1979), p. 245.

- ^ Gardiner (1979), pp. 339–340.

References

- Brown, David K., RCNC. Warrior to Dreadnought: Warship Design 1860–1905, London: Chatham, 1997 (reprinted 2003) ISBN 1-84067-529-2

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918: Navalism, Industrial Development, and the Politics of Dualism. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-034-9.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4.