| Catalan | |

|---|---|

| Valencian | |

| català, valencià | |

| Pronunciation | [kətəˈla], [valensiˈa] |

| Native to | Andorra, Spain, France, Italy |

| Region | Southern Europe |

| Ethnicity |

Catalans Aragonese from La Franja Balears Valencians |

| Speakers |

L1: 4.1 million (2012)

[1] L2: 5.1 million Total: 9.2 million |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

Standard forms | |

| Dialects |

|

|

Latin (

Catalan alphabet) Catalan Braille | |

| Signed Catalan | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

Andorra Italy |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by |

Institut d'Estudis Catalans Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

ca |

| ISO 639-2 |

cat |

| ISO 639-3 |

cat |

| Glottolog |

stan1289 |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAA-e |

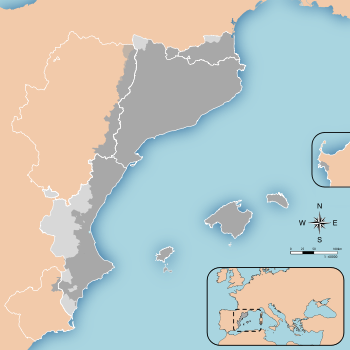

Territories where Catalan/Valencian is spoken and is official Territories where Catalan/Valencian is spoken but is not official Territories where Catalan/Valencian is not historically spoken but is official | |

Standard Catalan is classified as Vulnerable by the UNESCO

Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger

[3] | |

Catalan ( /ˈkætələn, -æn/ KAT-ə-lən, -lan or /ˌkætəˈlæn/ KAT-ə-LAN; [4] [5] autonym: català, Eastern Catalan: [kətəˈla]), known in the Valencian Community and Carche as Valencian ( autonym: valencià), is a Western Romance language. It is the official language of Andorra, [6] and an official language of three autonomous communities in eastern Spain: Catalonia, the Balearic Islands and the Valencian Community, where it is called Valencian. It has semi-official status in the Italian comune of Alghero, [7] and it is spoken in the Pyrénées-Orientales department of France and in two further areas in eastern Spain: the eastern strip of Aragon and the Carche area in the Region of Murcia. The Catalan-speaking territories are often called the Països Catalans or "Catalan Countries". [8]

The language evolved from Vulgar Latin in the Middle Ages around the eastern Pyrenees. Nineteenth-century Spain saw a Catalan literary revival, [9] [10] culminating in the early 1900s.

Etymology and pronunciation

The word Catalan is derived from the territorial name of Catalonia, itself of disputed etymology. The main theory suggests that Catalunya ( Latin Gathia Launia) derives from the name Gothia or Gauthia ("Land of the Goths"), since the origins of the Catalan counts, lords and people were found in the March of Gothia, whence Gothland > Gothlandia > Gothalania > Catalonia theoretically derived. [11] [12]

In English, the term referring to a person first appears in the mid 14th century as Catelaner, followed in the 15th century as Catellain (from French). It is attested a language name since at least 1652. The word Catalan can be pronounced in English as /ˈkætələn/, /ˈkætəlæn/ or /ˌkætəˈlæn/. [13] [5]

The endonym is pronounced [kətəˈla] in the Eastern Catalan dialects, and [kataˈla] in the Western dialects. In the Valencian Community and Carche, the term valencià [valensiˈa, ba-] is frequently used instead. Thus, the name "Valencian", although often employed for referring to the varieties specific to the Valencian Community and Carche, is also used by Valencians as a name for the language as a whole, [14] synonymous with "Catalan". [15] [14] Both uses of the term have their respective entries in the dictionaries by the Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua [note 1] and the Institut d'Estudis Catalans. [note 2] See also status of Valencian below.

History

Middle Ages

By the 9th century, Catalan had evolved from Vulgar Latin on both sides of the eastern end of the Pyrenees, as well as the territories of the Roman province of Hispania Tarraconensis to the south. [10] From the 8th century onwards the Catalan counts extended their territory southwards and westwards at the expense of the Muslims, bringing their language with them. [10] This process was given definitive impetus with the separation of the County of Barcelona from the Carolingian Empire in 988. [10]

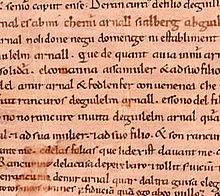

In the 11th century, documents written in macaronic Latin begin to show Catalan elements, [17] with texts written almost completely in Romance appearing by 1080. [17] Old Catalan shared many features with Gallo-Romance, diverging from Old Occitan between the 11th and 14th centuries. [18]

During the 11th and 12th centuries the Catalan rulers expanded southward to the Ebro river, [10] and in the 13th century they conquered the Land of Valencia and the Balearic Islands. [10] The city of Alghero in Sardinia was repopulated with Catalan speakers in the 14th century. The language also reached Murcia, which became Spanish-speaking in the 15th century. [19]

In the Low Middle Ages, Catalan went through a golden age, reaching a peak of maturity and cultural richness. [10] Examples include the work of Majorcan polymath Ramon Llull (1232–1315), the Four Great Chronicles (13th–14th centuries), and the Valencian school of poetry culminating in Ausiàs March (1397–1459). [10] By the 15th century, the city of Valencia had become the sociocultural center of the Crown of Aragon, and Catalan was present all over the Mediterranean world. [10] During this period, the Royal Chancery propagated a highly standardized language. [10] Catalan was widely used as an official language in Sicily until the 15th century, and in Sardinia until the 17th. [19] During this period, the language was what Costa Carreras terms "one of the 'great languages' of medieval Europe". [10]

Martorell's novel of chivalry Tirant lo Blanc (1490) shows a transition from Medieval to Renaissance values, something that can also be seen in Metge's work. [10] The first book produced with movable type in the Iberian Peninsula was printed in Catalan. [20] [10]

Start of the modern era

Spain

With the union of the crowns of Castille and Aragon in 1479, the Spanish kings ruled over different kingdoms, each with its own cultural, linguistic and political particularities, and they had to swear by the laws of each territory before the respective parliaments. But after the War of the Spanish Succession, Spain became an absolute monarchy under Philip V, which led to the assimilation of the Crown of Aragon by the Crown of Castile through the Nueva Planta decrees, as a first step in the creation of the Spanish nation-state; as in other contemporary European states, this meant the imposition of the political and cultural characteristics of the dominant groups. [21] [22] Since the political unification of 1714, Spanish assimilation policies towards national minorities have been a constant. [23] [24] [25] [26] [27][ neutrality is disputed]

The process of assimilation began with secret instructions to the corregidores of the Catalan territory: they "will take the utmost care to introduce the Castilian language, for which purpose he will give the most temperate and disguised measures so that the effect is achieved, without the care being noticed." [28] From there, actions in the service of assimilation, discreet or aggressive, were continued, and reached to the last detail, such as, in 1799, the Royal Certificate forbidding anyone to "represent, sing and dance pieces that were not in Spanish." [28] The use of Spanish gradually became more prestigious [19] and marked the start of the decline of Catalan. [10] [9] Starting in the 16th century, Catalan literature came under the influence of Spanish, and the nobles, part of the urban and literary classes became bilingual. [19]

France

With the Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659), Spain ceded the northern part of Catalonia to France, and soon thereafter the local Catalan varieties came under the influence of French, which in 1700 became the sole official language of the region. [6] [29]

Shortly after the French Revolution (1789), the French First Republic prohibited official use of, and enacted discriminating policies against, the regional languages of France, such as Catalan, Alsatian, Breton, Occitan, Flemish, and Basque.

France: 19th to 20th century

After the French colony of Algeria was established in 1830, many Catalan-speaking settlers moved there. People from the Spanish province of Alicante settled around Oran, while those from French Catalonia and Menorca migrated to Algiers.

By 1911, there were around 100,000 speakers of Patuet, [30] as their speech was called. [31] After the Algerian declaration of independence in 1962, almost all the Pied-Noir Catalan speakers fled to Northern Catalonia [32] or Alicante. [33]

The French government only recognizes French as an official language. Nevertheless, on 10 December 2007, the then General Council of the Pyrénées-Orientales officially recognized Catalan as one of the départment's languages [34] and seeks to further promote it in public life and education.

Spain: 18th to 20th century

In 1807, the Statistics Office of the French Ministry of the Interior asked the prefects for an official survey on the limits of the French language. The survey found that in Roussillon, almost only Catalan was spoken, and since Napoleon wanted to incorporate Catalonia into France, as happened in 1812, the consul in Barcelona was also asked. He declared that Catalan "is taught in schools, it is printed and spoken, not only among the lower class, but also among people of first quality, also in social gatherings, as in visits and congresses", indicating that it was spoken everywhere "with the exception of the royal courts". He also indicated that Catalan was spoken "in the Kingdom of Valencia, in the islands of Mallorca, Menorca, Ibiza, Sardinia, Corsica and much of Sicily, in the Vall d "Aran and Cerdaña". [35]

The defeat of the pro-Habsburg coalition in the War of Spanish Succession (1714) initiated a series of laws which, among other centralizing measures, imposed the use of Spanish in legal documentation all over Spain. Because of this, use of the Catalan language declined into the 18th century.

However, the 19th century saw a Catalan literary revival ( Renaixença), which has continued up to the present day. [6] This period starts with Aribau's Ode to the Homeland (1833); followed in the second half of the 19th century, and the early 20th by the work of Verdaguer (poetry), Oller (realist novel), and Guimerà (drama). [36] In the 19th century, the region of Carche, in the province of Murcia was repopulated with Valencian speakers. [37] Catalan spelling was standardized in 1913 and the language became official during the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1939). The Second Spanish Republic saw a brief period of tolerance, with most restrictions against Catalan lifted. [6] The Generalitat (the autonomous government of Catalonia, established during the Republic in 1931) made a normal use of Catalan in its administration and put efforts to promote it at social level, including in schools and the University of Barcelona.

The Catalan language and culture were still vibrant during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), but were crushed at an unprecedented level throughout the subsequent decades due to Francoist dictatorship (1939–1975), which abolished the official status of Catalan and imposed the use of Spanish in schools and in public administration in all of Spain, while banning the use of Catalan in them. [38] [9] Between 1939 and 1943 newspapers and book printing in Catalan almost disappeared. [39] Francisco Franco's desire for a homogenous Spanish population resonated with some Catalans in favor of his regime, primarily members of the upper class, who began to reject the use of Catalan. Despite all of these hardships, Catalan continued to be used privately within households, and it was able to survive Franco's dictatorship. At the end of World War II, however, some of the harsh mesures began to be lifted and, while Spanish language remained the sole promoted one, limited number of Catalan literature began to be tolerated. Several prominent Catalan authors resisted the suppression through literature. [40] Private initiative contests were created to reward works in Catalan, among them Joan Martorell prize (1947), Víctor Català prize (1953) Carles Riba award (1950), or the Honor Award of Catalan Letters (1969). [41] The first Catalan-language TV show was broadcast in 1964. [42] At the same time, oppression of the Catalan language and identity was carried out in schools, through governmental bodies, and in religious centers. [43]

In addition to the loss of prestige for Catalan and its prohibition in schools, migration during the 1950s into Catalonia from other parts of Spain also contributed to the diminished use of the language. These migrants were often unaware of the existence of Catalan, and thus felt no need to learn or use it. Catalonia was the economic powerhouse of Spain, so these migrations continued to occur from all corners of the country. Employment opportunities were reduced for those who were not bilingual. [44] Daily newspapers remained exclusively in Spanish until after Franco's death, when the first one in Catalan since the end of the Civil War, Avui, began to be published in 1976. [45]

Present day

Since the Spanish transition to democracy (1975–1982), Catalan has been institutionalized as an official language, language of education, and language of mass media; all of which have contributed to its increased prestige. [46] In Catalonia, there is an unparalleled large bilingual European non-state linguistic community. [46] The teaching of Catalan is mandatory in all schools, [6] but it is possible to use Spanish for studying in the public education system of Catalonia in two situations – if the teacher assigned to a class chooses to use Spanish, or during the learning process of one or more recently arrived immigrant students. [47] There is also some intergenerational shift towards Catalan. [6]

More recently, several Spanish political forces have tried to increase the use of Spanish in the Catalan educational system. [48] As a result, in May 2022 the Spanish Supreme Court urged the Catalan regional government to enforce a measure by which 25% of all lessons must be taught in Spanish. [49]

According to the Statistical Institute of Catalonia, in 2013 the Catalan language is the second most commonly used in Catalonia, after Spanish, as a native or self-defining language: 7% of the population self-identifies with both Catalan and Spanish equally, 36.4% with Catalan and 47.5% only Spanish. [50] In 2003 the same studies concluded no language preference for self-identification within the population above 15 years old: 5% self-identified with both languages, 44.3% with Catalan and 47.5% with Spanish. [51] To promote use of Catalan, the Generalitat de Catalunya (Catalonia's official Autonomous government) spends part of its annual budget on the promotion of the use of Catalan in Catalonia and in other territories, with entities such as Consorci per a la Normalització Lingüística [ ca; es] (Consortium for Linguistic Normalization) [52] [53]

In Andorra, Catalan has always been the sole official language. [6] Since the promulgation of the 1993 constitution, several policies favoring Catalan have been enforced, like Catalan medium education. [6]

On the other hand, there are several language shift processes currently taking place. In the Northern Catalonia area of France, Catalan has followed the same trend as the other minority languages of France, with most of its native speakers being 60 or older (as of 2004). [6] Catalan is studied as a foreign language by 30% of the primary education students, and by 15% of the secondary. [6] The cultural association La Bressola promotes a network of community-run schools engaged in Catalan language immersion programs.

In Alicante province, Catalan is being replaced by Spanish and in Alghero by Italian. [46] There is also well ingrained diglossia in the Valencian Community, Ibiza, and to a lesser extent, in the rest of the Balearic islands. [6]

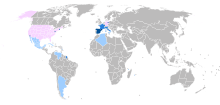

During the 20th century many Catalans emigrated or went into exile to Venezuela, Mexico, Cuba, Argentina, and other South American countries. They formed a large number of Catalan colonies that today continue to maintain the Catalan language. [54] [55] They also founded many Catalan casals (associations). [56]

Classification and relationship with other Romance languages

One classification of Catalan is given by Pèire Bèc:

However, the ascription of Catalan to the Occitano-Romance branch of Gallo-Romance languages is not shared by all linguists and philologists, particularly among Spanish ones, such as Ramón Menéndez Pidal.

Catalan bears varying degrees of similarity to the linguistic varieties subsumed under the cover term Occitan language (see also differences between Occitan and Catalan and Gallo-Romance languages). Thus, as it should be expected from closely related languages, Catalan today shares many traits with other Romance languages.

Relationship with other Romance languages

Some include Catalan in Occitan, as the linguistic distance between this language and some Occitan dialects (such as the Gascon dialect) is similar to the distance among different Occitan dialects. Catalan was considered a dialect of Occitan until the end of the 19th century [57] and still today remains its closest relative. [58]

Catalan shares many traits with the other neighboring Romance languages (Occitan, French, Italian, Sardinian as well as Spanish and Portuguese among others). [37] However, despite being spoken mostly on the Iberian Peninsula, Catalan has marked differences with the Iberian Romance group ( Spanish and Portuguese) in terms of pronunciation, grammar, and especially vocabulary; it shows instead its closest affinity with languages native to France and northern Italy, particularly Occitan [59] [60] [61] and to a lesser extent Gallo-Romance ( Franco-Provençal, French, Gallo-Italian). [62] [63] [64] [65] [59] [60] [61]

According to Ethnologue, the lexical similarity between Catalan and other Romance languages is: 87% with Italian; 85% with Portuguese and Spanish; 76% with Ladin and Romansh; 75% with Sardinian; and 73% with Romanian. [1]

| Gloss | Catalan | Occitan | ( Campidanese) Sardinian | Italian | French | Spanish | Portuguese | Romanian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cousin | cosí | cosin | fradili | cugino | cousin | primo | primo, coirmão | văr |

| brother | germà | fraire | fradi | fratello | frère | hermano | irmão | frate |

| nephew | nebot | nebot | nebodi | nipote | neveu | sobrino | sobrinho | nepot |

| summer | estiu | estiu | istadi | estate | été | verano, estío [66] | verão, estio [66] | vară |

| evening | vespre | ser, vèspre | seru | sera | soir | tarde, noche [67] | tarde, serão [67] | seară |

| morning | matí | matin | mangianu | mattina | matin | mañana | manhã, matina | dimineață |

| frying pan | paella | padena | paella | padella | poêle | sartén | frigideira, fritadeira | tigaie |

| bed | llit | lièch, lèit | letu | letto | lit | cama, lecho | cama, leito | pat |

| bird | ocell, au | aucèl | pilloni | uccello | oiseau | ave, pájaro | ave, pássaro | pasăre |

| dog | gos, ca | gos, canh | cani | cane | chien | perro, can | cão, cachorro | câine |

| plum | pruna | pruna | pruna | prugna | prune | ciruela | ameixa | prună |

| butter | mantega | bodre | burru, butiru | burro | beurre | mantequilla, manteca | manteiga | unt |

| piece | tros | tròç, petaç | arrogu | pezzo | morceau, pièce | pedazo, trozo [68] | pedaço, bocado | bucată |

| gray | gris | gris | canu | grigio | gris | gris, pardo [69] | cinzento, gris | gri, [70] sur, cenușiu |

| hot | calent | caud | callenti | caldo | chaud | caliente | quente | cald |

| too much | massa | tròp | tropu | troppo | trop | demasiado | demais, demasiado | prea |

| to want | voler | vòler | bolli(ri) | volere | vouloir | querer | querer | a vrea |

| to take | prendre | prene, prendre | pigai | prendere | prendre | tomar, prender | apanhar, levar | a lua |

| to pray | pregar | pregar | pregai | pregare | prier | orar | orar, rezar, pregar | a se ruga |

| to ask | demanar/preguntar | demandar | dimandai, preguntai | domandare | demander | pedir, preguntar | pedir, perguntar | a cere, a întreba |

| to search | cercar/buscar | cercar | circai | cercare | chercher | buscar | procurar, buscar | a căuta |

| to arrive | arribar | arribar | arribai | arrivare | arriver | llegar, arribar | chegar | a ajunge |

| to speak | parlar | parlar | chistionnai, fueddai | parlare | parler | hablar, parlar | falar, palrar | a vorbi |

| to eat | menjar | manjar | pappai | mangiare | manger | comer (manyar in lunfardo; papear in slang) | comer (papar in slang), manjar | a mânca |

| Latin | Catalan | Spanish |

|---|---|---|

| accostare | acostar "to bring closer" | acostar "to put to bed" |

| levare |

llevar "to remove; wake up" |

llevar "to take" |

| trahere | traure "to remove" | traer "to bring" |

| circare | cercar "to search" | cercar "to fence" |

| collocare | colgar "to bury" | colgar "to hang" |

| mulier | muller "wife" | mujer "woman or wife" |

During much of its history, and especially during the Francoist dictatorship (1939–1975), the Catalan language was ridiculed as a mere dialect of Spanish. [60] [61] This view, based on political and ideological considerations, has no linguistic validity. [60] [61] Spanish and Catalan have important differences in their sound systems, lexicon, and grammatical features, placing the language in features closer to Occitan (and French). [60] [61]

There is evidence that, at least from the 2nd century a.d., the vocabulary and phonology of Roman Tarraconensis was different from the rest of Roman Hispania. [59] Differentiation arose generally because Spanish, Asturian, and Galician-Portuguese share certain peripheral archaisms (Spanish hervir, Asturian and Portuguese ferver vs. Catalan bullir, Occitan bolir "to boil") and innovatory regionalisms (Sp novillo, Ast nuviellu vs. Cat torell, Oc taurèl "bullock"), while Catalan has a shared history with the Western Romance innovative core, especially Occitan. [71] [59]

Like all Romance languages, Catalan has a handful of native words which are unique to it, or rare elsewhere. These include:

- verbs: cōnfīgere 'to fasten; transfix' > confegir 'to compose, write up', congemināre > conjuminar 'to combine, conjugate', de-ex-somnitare > deixondar/-ir 'to wake; awaken', dēnsāre 'to thicken; crowd together' > desar 'to save, keep', īgnōrāre > enyorar 'to miss, yearn, pine for', indāgāre 'to investigate, track' > Old Catalan enagar 'to incite, induce', odiāre > OCat ujar 'to exhaust, fatigue', pācificāre > apaivagar 'to appease, mollify', repudiāre > rebutjar 'to reject, refuse';

- nouns: brīsa > brisa 'pomace', buda > boga 'reedmace', catarrhu > cadarn 'catarrh', congesta > congesta 'snowdrift', dēlīrium > deler 'ardor, passion', fretu > freu 'brake', lābem > (a)llau 'avalanche', ōra > vora 'edge, border', pistrīce 'sawfish' > pestriu > pestiu 'thresher shark, smooth hound; ray', prūna 'live coal' > espurna 'spark', tardātiōnem > tardaó > tardor 'autumn'. [72][ clarification needed]

The Gothic superstrate produced different outcomes in Spanish and Catalan. For example, Catalan fang "mud" and rostir "to roast", of Germanic origin, contrast with Spanish lodo and asar, of Latin origin; whereas Catalan filosa "spinning wheel" and templa "temple", of Latin origin, contrast with Spanish rueca and sien, of Germanic origin. [59]

The same happens with Arabic loanwords. Thus, Catalan alfàbia "large earthenware jar" and rajola "tile", of Arabic origin, contrast with Spanish tinaja and teja, of Latin origin; whereas Catalan oli "oil" and oliva "olive", of Latin origin, contrast with Spanish aceite and aceituna. [59] However, the Arabic element is generally much more prevalent in Spanish. [59]

Situated between two large linguistic blocks (Iberian Romance and Gallo-Romance), Catalan has many unique lexical choices, such as enyorar "to miss somebody", apaivagar "to calm somebody down", and rebutjar "reject". [59]

Geographic distribution

Catalan-speaking territories

Traditionally Catalan-speaking territories are sometimes called the Països Catalans (Catalan Countries), a denomination based on cultural affinity and common heritage, that has also had a subsequent political interpretation but no official status. Various interpretations of the term may include some or all of these regions.

| State | Territory | Catalan name | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Andorra | Andorra | Andorra | A sovereign state where Catalan is the national and the sole official language. The Andorrans speak a Western Catalan variety. [b] |

| France | Northern Catalonia | Catalunya Nord | Roughly corresponding to the département of Pyrénées-Orientales. [37] |

| Spain | Catalonia | Catalunya | In the Aran Valley (northwest corner of Catalonia), in addition to Occitan, which is the local language, Catalan, Spanish and French are also spoken. [37] |

| Valencian Community | Comunitat Valenciana | Excepting some regions in the west and south which have been Aragonese/Spanish-speaking since at least the 18th century. [37] The Western Catalan variety spoken there is known as " Valencian". | |

La Franja |

La Franja | A part of the Autonomous Community of Aragon, specifically a strip bordering Western Catalonia. It comprises the comarques of Ribagorça, Llitera, Baix Cinca, and Matarranya. | |

| Balearic Islands | Illes Balears | Comprising the islands of Mallorca, Menorca, Ibiza and Formentera. | |

| Carche | El Carxe | A small area of the Autonomous Community of Murcia, settled in the 19th century. [37] | |

| Italy | Alghero | L'Alguer | A city in the Province of Sassari, on the island of Sardinia, where the Algherese dialect is spoken. |

Number of speakers

The number of people known to be fluent in Catalan varies depending on the sources used. A 2004 study did not count the total number of speakers, but estimated a total of 9–9.5 million by matching the percentage of speakers to the population of each area where Catalan is spoken. [73] The web site of the Generalitat de Catalunya estimated that as of 2004 there were 9,118,882 speakers of Catalan. [74] These figures only reflect potential speakers; today it is the native language of only 35.6% of the Catalan population. [75] According to Ethnologue, Catalan had 4.1 million native speakers and 5.1 million second-language speakers in 2021. [1]

According to a 2011 study the total number of Catalan speakers was over 9.8 million, with 5.9 million residing in Catalonia. More than half of them spoke Catalan as a second language, with native speakers being about 4.4 million of those (more than 2.8 in Catalonia). [76] Very few Catalan monoglots exist; basically, virtually all of the Catalan speakers in Spain are bilingual speakers of Catalan and Spanish, with a sizable population of Spanish-only speakers of immigrant origin (typically born outside Catalonia or whose parents were both born outside Catalonia) [ citation needed] existing in the major Catalan urban areas as well.

In Roussillon, only a minority of French Catalans speak Catalan nowadays, with French being the majority language for the inhabitants after a continued process of language shift. According to a 2019 survey by the Catalan government, 31.5% of the inhabitants of Catalonia predominantly spoke Catalan at home whereas 52.7% spoke Spanish, 2.8% both Catalan and Spanish and 10.8% other languages. [77]

Spanish was the most spoken language in Barcelona (according to the linguistic census held by the Government of Catalonia in 2013) and it is understood almost universally. According to 2013 census, Catalan was also very commonly spoken in the city of 1,501,262: it was understood by 95% of the population, while 72.3% over the age of two could speak it (1,137,816), 79% could read it (1,246.555), and 53% could write it (835,080). [78] The share of Barcelona residents who could speak it (72.3%) [79] was lower than that of the overall Catalan population, of whom 81.2% over the age of 15 spoke the language. Knowledge of Catalan has increased significantly in recent decades thanks to a language immersion educational system. An important social characteristic of the Catalan language is that all the areas where it is spoken are bilingual in practice: together with French in Roussillon, with Italian in Alghero, with Spanish and French in Andorra, and with Spanish in the rest of the territories.

| Territory | State | Understand 1 [80] | Can speak 2 [80] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalonia | Spain | 6,502,880 | 5,698,400 |

| Valencian Community | Spain | 3,448,780 | 2,407,951 |

| Balearic Islands | Spain | 852,780 | 706,065 |

| Roussillon | France | 203,121 | 125,621 |

| Andorra | Andorra | 75,407 | 61,975 |

| La Franja ( Aragon) | Spain | 47,250 | 45,000 |

| Alghero ( Sardinia) | Italy | 20,000 | 17,625 |

| Carche ( Murcia) | Spain | ~600 | 600 [81] |

| Total Catalan-speaking territories | 11,150,218 | 9,062,637 | |

| Rest of World | No data | 350,000 | |

| Total | 11,150,218 | 9,412,637 | |

- 1. ^ The number of people who understand Catalan includes those who can speak it.

- 2. ^ Figures relate to all self-declared capable speakers, not just native speakers.

Level of knowledge

| Area | Speak | Understand | Read | Write |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catalonia [82] | 81.2 | 94.4 | 85.5 | 65.3 |

| Valencian Community | 57.5 | 78.1 | 54.9 | 32.5 |

| Balearic Islands | 74.6 | 93.1 | 79.6 | 46.9 |

| Roussillon | 37.1 | 65.3 | 31.4 | 10.6 |

| Andorra | 78.9 | 96.0 | 89.7 | 61.1 |

| Franja Oriental of Aragón | 88.8 | 98.5 | 72.9 | 30.3 |

| Alghero | 67.6 | 89.9 | 50.9 | 28.4 |

(% of the population 15 years old and older).

Social use

| Area | At home | Outside home |

|---|---|---|

| Catalonia | 45 | 51 |

| Valencian Community | 37 | 32 |

| Balearic Islands | 44 | 41 |

| Roussillon | 1 | 1 |

| Andorra | 38 | 51 |

| Franja Oriental of Aragón | 70 | 61 |

| Alghero | 8 | 4 |

(% of the population 15 years old and older).

Native language

| Area | People | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Catalonia | 2,813,000 | 38.5% |

| Valencian Community | 1,047,000 | 21.1% |

| Balearic Islands | 392,000 | 36.1% |

| Andorra | 26,000 | 33.8% |

| Franja Oriental of Aragon | 33,000 | 70.2% |

| Roussillon | 35,000 | 8.5% |

| Alghero | 8,000 | 20% |

| TOTAL | 4,353,000 | 31.2% |

Phonology

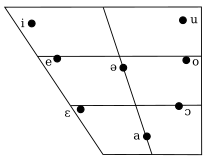

Catalan phonology varies by dialect. Notable features include: [86]

- Marked contrast of the vowel pairs /ɛ e/ and /ɔ o/, as in other Western Romance languages, other than Spanish. [86]

- Lack of diphthongization of Latin short ĕ, ŏ, as in Galician and Portuguese, but unlike French, Spanish, or Italian. [86]

- Abundance of diphthongs containing /w/, as in Galician and Portuguese. [86]

In contrast to other Romance languages, Catalan has many monosyllabic words, and these may end in a wide variety of consonants, including some consonant clusters. [86] Additionally, Catalan has final obstruent devoicing, which gives rise to an abundance of such couplets as amic ("male friend") vs. amiga ("female friend"). [86]

Central Catalan pronunciation is considered to be standard for the language. [87] The descriptions below are mostly representative of this variety. [88] For the differences in pronunciation between the different dialects, see the section on pronunciation of dialects in this article.

Vowels

Catalan has inherited the typical vowel system of Vulgar Latin, with seven stressed phonemes: /a ɛ e i ɔ o u/, a common feature in Western Romance, with the exception of Spanish. [86] Balearic also has instances of stressed /ə/. [90] Dialects differ in the different degrees of vowel reduction, [91] and the incidence of the pair /ɛ e/. [92]

In Central Catalan, unstressed vowels reduce to three: /a e ɛ/ > [ə]; /o ɔ u/ > [u]; /i/ remains distinct. [93] The other dialects have different vowel reduction processes (see the section pronunciation of dialects in this article).

| Front vowels | Back vowels | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Word pair |

gel ("ice") gelat ("ice cream") |

pedra ("stone") pedrera ("quarry") |

banya ("he bathes") banyem ("we bathe") |

cosa ("thing") coseta ("little thing") |

tot ("everything") total ("total") |

| IPA transcription |

[ˈʒɛl] [ʒəˈlat] |

[ˈpeðɾə] [pəˈðɾeɾə] |

[ˈbaɲə] [bəˈɲɛm] |

[ˈkɔzə] [kuˈzɛtə] |

[ˈtot] [tuˈtal] |

Consonants

| Bilabial |

Alveolar / Dental |

Palatal | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | |

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | c ~ k | |

| voiced | b | d | ɟ ~ ɡ | ||

| Affricate | voiceless | ts | tʃ | ||

| voiced | dz | dʒ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | |

| voiced | ( v) | z | ʒ | ||

| Approximant | central | j | w | ||

| lateral | l | ʎ | |||

| Tap | ɾ | ||||

| Trill | r | ||||

The consonant system of Catalan is rather conservative.

- /l/ has a velarized allophone in syllable coda position in most dialects. [96] However, /l/ is velarized irrespective of position in Eastern dialects like Majorcan [97] and standard Eastern Catalan.

- /v/ occurs in Balearic, [98] Algherese, standard Valencian and some areas in southern Catalonia. [99] It has merged with /b/ elsewhere. [100]

- Voiced obstruents undergo final-obstruent devoicing: /b/ > [p], /d/ > [t], /ɡ/ > [k]. [101]

- Voiced stops become lenited to approximants in syllable onsets, after continuants: /b/ > [ β], /d/ > [ ð], /ɡ/ > [ ɣ]. [102] Exceptions include /d/ after lateral consonants, and /b/ after /f/. In coda position, these sounds are realized as stops, [103] except in some Valencian dialects where they are lenited. [104]

- There is some confusion in the literature about the precise phonetic characteristics of /ʃ/, /ʒ/, /tʃ/, /dʒ/. Some sources [98] describe them as "postalveolar". Others [105] [106] as "back alveolo-palatal", implying that the characters ⟨ɕ ʑ tɕ dʑ⟩ would be more accurate. However, in all literature only the characters for palato-alveolar affricates and fricatives are used, even when the same sources use ⟨ɕ ʑ⟩ for other languages like Polish and Chinese. [107] [108] [106]

- The distribution of the two rhotics /r/ and /ɾ/ closely parallels that of Spanish. Between vowels, the two contrast, but they are otherwise in complementary distribution: in the onset of the first syllable in a word, [ r] appears unless preceded by a consonant. Dialects vary in regards to rhotics in the coda with Western Catalan generally featuring [ ɾ] and Central Catalan dialects featuring a weakly trilled [ r] unless it precedes a vowel-initial word in the same prosodic unit, in which case [ ɾ] appears. [109]

- In careful speech, /n/, /m/, /l/ may be geminated. Geminated /ʎ/ may also occur. [98] Some analyze intervocalic [r] as the result of gemination of a single rhotic phoneme. [110] This is similar to the common analysis of Spanish and Portuguese rhotics. [111]

Phonological evolution

Sociolinguistics

Catalan sociolinguistics studies the situation of Catalan in the world and the different varieties that this language presents. It is a subdiscipline of Catalan philology and other affine studies and has as an objective to analyze the relation between the Catalan language, the speakers and the close reality (including the one of other languages in contact).

Preferential subjects of study

- Dialects of Catalan

- Variations of Catalan by class, gender, profession, age and level of studies

- Process of linguistic normalization

- Relations between Catalan and Spanish or French

- Perception on the language of Catalan speakers and non-speakers

- Presence of Catalan in several fields: tagging, public function, media, professional sectors

Dialects

Overview

The dialects of the Catalan language feature a relative uniformity, especially when compared to other Romance languages; [65] both in terms of vocabulary, semantics, syntax, morphology, and phonology. [115] Mutual intelligibility between dialects is very high, [37] [116] [87] estimates ranging from 90% to 95%. [1] The only exception is the isolated idiosyncratic Algherese dialect. [65]

Catalan is split in two major dialectal blocks: Eastern and Western. [87] [115] The main difference lies in the treatment of unstressed a and e; which have merged to /ə/ in Eastern dialects, but which remain distinct as /a/ and /e/ in Western dialects. [65] [87] There are a few other differences in pronunciation, verbal morphology, and vocabulary. [37]

Western Catalan comprises the two dialects of Northwestern Catalan and Valencian; the Eastern block comprises four dialects: Central Catalan, Balearic, Rossellonese, and Algherese. [87] Each dialect can be further subdivided in several subdialects. The terms "Catalan" and " Valencian" (respectively used in Catalonia and the Valencian Community) refer to two varieties of the same language. [117] There are two institutions regulating the two standard varieties, the Institute of Catalan Studies in Catalonia and the Valencian Academy of the Language in the Valencian Community.

Central Catalan is considered the standard pronunciation of the language and has the largest number of speakers. [87] It is spoken in the densely populated regions of the Barcelona province, the eastern half of the province of Tarragona, and most of the province of Girona. [87]

Catalan has an inflectional grammar. Nouns have two genders (masculine, feminine), and two numbers (singular, plural). Pronouns additionally can have a neuter gender, and some are also inflected for case and politeness, and can be combined in very complex ways. Verbs are split in several paradigms and are inflected for person, number, tense, aspect, mood, and gender. In terms of pronunciation, Catalan has many words ending in a wide variety of consonants and some consonant clusters, in contrast with many other Romance languages. [86]

| Block | Western Catalan | Eastern Catalan | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dialect | Northwestern | Valencian | Central | Balearic | Northern/Rossellonese | Algherese |

| Area | Spain, Andorra | Spain | France | Italy | ||

| Andorra, Provinces of Lleida, western half of Tarragona, La Franja | Autonomous community of Valencia, Carche | Provinces of Barcelona, eastern half of Tarragona, most of Girona | Balearic islands | Roussillon/ Northern Catalonia | City of Alghero in Sardinia | |

Pronunciation

Vowels

Catalan has inherited the typical vowel system of Vulgar Latin, with seven stressed phonemes: /a ɛ e i ɔ o u/, a common feature in Western Romance, except Spanish. [86] Balearic has also instances of stressed /ə/. [90] Dialects differ in the different degrees of vowel reduction, [91] and the incidence of the pair /ɛ e/. [92]

In Eastern Catalan (except Majorcan), unstressed vowels reduce to three: /a e ɛ/ > [ə]; /o ɔ u/ > [u]; /i/ remains distinct. [93] There are a few instances of unreduced [e], [o] in some words. [93] Algherese has lowered [ə] to [a].

In Majorcan, unstressed vowels reduce to four: /a e ɛ/ follow the Eastern Catalan reduction pattern; however /o ɔ/ reduce to [o], with /u/ remaining distinct, as in Western Catalan. [119]

In Western Catalan, unstressed vowels reduce to five: /e ɛ/ > [e]; /o ɔ/ > [o]; /a u i/ remain distinct. [120] [121] This reduction pattern, inherited from Proto-Romance, is also found in Italian and Portuguese. [120] Some Western dialects present further reduction or vowel harmony in some cases. [120] [122]

Central, Western, and Balearic differ in the lexical incidence of stressed /e/ and /ɛ/. [92] Usually, words with /ɛ/ in Central Catalan correspond to /ə/ in Balearic and /e/ in Western Catalan. [92] Words with /e/ in Balearic almost always have /e/ in Central and Western Catalan as well.[ vague] [92] As a result, Central Catalan has a much higher incidence of /ɛ/. [92]

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Word pairs: the first with stressed root, the second with unstressed root |

Western | Eastern | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Majorcan | Central | Northern | |||

| Front vowels |

gel ("ice") gelat ("ice cream") |

[ˈdʒɛl] [dʒeˈlat] |

[ˈʒɛl] [ʒəˈlat] |

[ˈʒel] [ʒəˈlat] | |

| pera ("pear") perera ("pear tree") |

[ˈpeɾa] [peˈɾeɾa] |

[ˈpəɾə] [pəˈɾeɾə] |

[ˈpɛɾə] [pəˈɾeɾə] |

[ˈpeɾə] [pəˈɾeɾə] | |

| pedra ("stone") pedrera ("quarry") |

[ˈpeðɾa] [peˈðɾeɾa] |

[ˈpeðɾə] [pəˈðɾeɾə] | |||

| banya ("he bathes") banyem ("we bathe") Majorcan: banyam ("we bathe") |

[ˈbaɲa] [baˈɲem] |

[ˈbaɲə] [bəˈɲam] |

[ˈbaɲə] [bəˈɲɛm] |

[ˈbaɲə] [bəˈɲem] | |

| Back vowels |

cosa ("thing") coseta ("little thing") |

[ˈkɔza] [koˈzeta] |

[ˈkɔzə] [koˈzətə] |

[ˈkɔzə] [kuˈzɛtə] |

[ˈkozə] [kuˈzetə] |

| tot ("everything") total ("total") |

[ˈtot] [toˈtal] |

[ˈtot] [tuˈtal] |

[ˈtut] [tuˈtal] | ||

Consonants

|

| This section needs expansion. You can help by

adding to it. (March 2014) |

Morphology

Western Catalan: In verbs, the ending for 1st-person present indicative is -e in verbs of the 1st conjugation and -∅ in verbs of the 2nd and 3rd conjugations in most of the Valencian Community, or -o in all verb conjugations in the Northern Valencian Community and Western Catalonia.

E.g. parle, tem, sent (Valencian); parlo, temo, sento (Northwestern Catalan).

Eastern Catalan: In verbs, the ending for 1st-person present indicative is -o, -i, or -∅ in all conjugations.

E.g. parlo (Central), parl (Balearic), and parli (Northern), all meaning ('I speak').

| Conjugation | Eastern Catalan | Western Catalan | Gloss | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central | Northern | Balearic | Valencian | Northwestern | ||||

| 1st | parlo | parli | parl | parle | parlo | 'I speak' | ||

| 2nd | temo | temi | tem | tem | temo | 'I fear' | ||

| 3rd | pure | sento | senti | sent | sent | sento | 'I feel', 'I hear' | |

| inchoative | poleixo | poleixi | poleix or polesc | polisc or polesc | pol(e)ixo | 'I polish' | ||

Western Catalan: In verbs, the inchoative endings are -isc/-esc, -ix, -ixen, -isca/-esca.

Eastern Catalan: In verbs, the inchoative endings are -eixo, -eix, -eixen, -eixi.

Western Catalan: In nouns and adjectives, maintenance of /n/ of medieval plurals in

proparoxytone words.

E.g. hòmens 'men', jóvens 'youth'.

Eastern Catalan: In nouns and adjectives, loss of /n/ of medieval plurals in proparoxytone words.

E.g. homes 'men', joves 'youth' (Ibicencan, however, follows the model of Western Catalan in this case

[124]).

Vocabulary

Despite its relative lexical unity, the two dialectal blocks of Catalan (Eastern and Western) show some differences in word choices. [59] Any lexical divergence within any of the two groups can be explained as an archaism. Also, usually Central Catalan acts as an innovative element. [59]

| Gloss | "mirror" | "boy" | "broom" | "navel" | "to exit" |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern Catalan | mirall | noi | escombra | llombrígol | sortir |

| Western Catalan | espill | xiquet | granera | melic | eixir |

Standards

| Catalan (IEC) | Valencian (AVL) | gloss |

|---|---|---|

| anglès | anglés | English |

| conèixer | conéixer | to know |

| treure | traure | take out |

| néixer | nàixer | to be born |

| càntir | cànter | pitcher |

| rodó | redó | round |

| meva | meua | my, mine |

| ametlla | ametla | almond |

| estrella | estrela | star |

| cop | colp | hit |

| llagosta | llangosta | lobster |

| homes | hòmens | men |

| servei | servici | service |

Standard Catalan, virtually accepted by all speakers, [46] is mostly based on Eastern Catalan, [87] [125] which is the most widely used dialect. Nevertheless, the standards of the Valencian Community and the Balearics admit alternative forms, mostly traditional ones, which are not current in eastern Catalonia. [125]

The most notable difference between both standards is some tonic ⟨e⟩ accentuation, for instance: francès, anglès (IEC) – francés, anglés (AVL). Nevertheless, AVL's standard keeps the grave accent ⟨è⟩, while pronouncing it as /e/ rather than /ɛ/, in some words like: què ('what'), or València. Other divergences include the use of ⟨tl⟩ (AVL) in some words instead of ⟨tll⟩ like in ametla/ametlla ('almond'), espatla/espatlla ('back'), the use of elided demonstratives (este 'this', eixe 'that') in the same level as reinforced ones (aquest, aqueix) or the use of many verbal forms common in Valencian, and some of these common in the rest of Western Catalan too, like subjunctive mood or inchoative conjugation in -ix- at the same level as -eix- or the priority use of -e morpheme in 1st person singular in present indicative (-ar verbs): jo compre instead of jo compro ('I buy').

In the Balearic Islands, IEC's standard is used but adapted for the Balearic dialect by the University of the Balearic Islands's philological section. In this way, for instance, IEC says it is correct writing cantam as much as cantem ('we sing'), but the university says that the priority form in the Balearic Islands must be cantam in all fields. Another feature of the Balearic standard is the non-ending in the 1st person singular present indicative: jo compr ('I buy'), jo tem ('I fear'), jo dorm ('I sleep').

In Alghero, the IEC has adapted its standard to the Algherese dialect. In this standard one can find, among other features: the definite article lo instead of el, special possessive pronouns and determinants la mia ('mine'), lo sou/la sua ('his/her'), lo tou/la tua ('yours'), and so on, the use of -v- /v/ in the imperfect tense in all conjugations: cantava, creixiva, llegiva; the use of many archaic words, usual words in Algherese: manco instead of menys ('less'), calqui u instead of algú ('someone'), qual/quala instead of quin/quina ('which'), and so on; and the adaptation of weak pronouns. In 1999, Catalan ( Algherese dialect) was among the twelve minority languages officially recognized as Italy's " historical linguistic minorities" by the Italian State under Law No. 482/1999. [126]

In 2011, [127] the Aragonese government passed a decree approving the statutes of a new language regulator of Catalan in La Franja (the so-called Catalan-speaking areas of Aragon) as originally provided for by Law 10/2009. [128] The new entity, designated as Institut Aragonès del Català, shall allow a facultative education in Catalan and a standardization of the Catalan language in La Franja.

Status of Valencian

Valencian is classified as a Western dialect, along with the northwestern varieties spoken in Western Catalonia (provinces of Lleida and the western half of Tarragona). [87] [118] Central Catalan has 90% to 95% inherent intelligibility for speakers of Valencian. [1]

Linguists, including Valencian scholars, deal with Catalan and Valencian as the same language. The official regulating body of the language of the Valencian Community, the Valencian Academy of Language (Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua, AVL) declares the linguistic unity between Valencian and Catalan varieties. [14]

[T]he historical patrimonial language of the Valencian people, from a philological standpoint, is the same shared by the autonomous communities of Catalonia and Balearic islands, and Principality of Andorra. Additionally, it is the patrimonial historical language of other territories of the ancient Crown of Aragon [...] The different varieties of these territories constitute a language, that is, a "linguistic system" [...] From this group of varieties, Valencian has the same hierarchy and dignity as any other dialectal modality of that linguistic system [...]

Ruling of the Valencian Language Academy of 9 February 2005, extract of point 1. [14] [129]

The AVL, created by the Valencian parliament, is in charge of dictating the official rules governing the use of Valencian, and its standard is based on the Norms of Castelló ( Normes de Castelló). Currently, everyone who writes in Valencian uses this standard, except the Royal Academy of Valencian Culture (Acadèmia de Cultura Valenciana, RACV), which uses an independent standard for Valencian.

Despite the position of the official organizations, an opinion poll carried out between 2001 and 2004 [130] showed that the majority of the Valencian people consider Valencian different from Catalan. This position is promoted by people who do not use Valencian regularly. [46] Furthermore, the data indicates that younger generations educated in Valencian are much less likely to hold these views. A minority of Valencian scholars active in fields other than linguistics defends the position of the Royal Academy of Valencian Culture (Acadèmia de Cultura Valenciana, RACV), which uses for Valencian a standard independent from Catalan. [131]

This clash of opinions has sparked much controversy. For example, during the drafting of the European Constitution in 2004, the Spanish government supplied the EU with translations of the text into Basque, Galician, Catalan, and Valencian, but the latter two were identical. [132]

Vocabulary

Word choices

Despite its relative lexical unity, the two dialectal blocks of Catalan (Eastern and Western) show some differences in word choices. [59] Any lexical divergence within any of the two groups can be explained as an archaism. Also, usually Central Catalan acts as an innovative element. [59]

Literary Catalan allows the use of words from different dialects, except those of very restricted use. [59] However, from the 19th century onwards, there has been a tendency towards favoring words of Northern dialects to the detriment of others, even though nowadays there is a greater freedom of choice.[ clarify] [59]

Latin and Greek loanwords

Like other languages, Catalan has a large list of loanwords from Greek and Latin. This process started very early, and one can find such examples in Ramon Llull's work. [59] In the 14th and 15th centuries Catalan had a far greater number of Greco-Latin loanwords than other Romance languages, as is attested for example in Roís de Corella's writings. [59] The incorporation of learned, or "bookish" words from its own ancestor language, Latin, into Catalan is arguably another form of lexical borrowing through the influence of written language and the liturgical language of the Church. Throughout the Middle Ages and into the early modern period, most literate Catalan speakers were also literate in Latin; and thus they easily adopted Latin words into their writing—and eventually speech—in Catalan.

Word formation

The process of morphological derivation in Catalan follows the same principles as the other Romance languages, [133] where agglutination is common. Many times, several affixes are appended to a preexisting lexeme, and some sound alternations can occur, for example elèctric [əˈlɛktrik ("electrical") vs. electricitat [ələktrisiˈtat]. Prefixes are usually appended to verbs, as in preveure ("foresee"). [133]

There is greater regularity in the process of word-compounding, where one can find compounded words formed much like those in English. [133]

| Type | Example | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| two nouns, the second assimilated to the first | paper moneda | "banknote paper" |

| noun delimited by an adjective | estat major | "military staff" |

| noun delimited by another noun and a preposition | màquina d'escriure | "typewriter" |

| verb radical with a nominal object | paracaigudes | "parachute" |

| noun delimited by an adjective, with adjectival value | pit-roig | "robin" (bird) |

Writing system

| Main forms | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modified forms | À | Ç | É È | Í Ï | L·L | Ó Ò | Ú Ü | |||||||||||||||||||

Catalan uses the Latin script, with some added symbols and digraphs. [134] The Catalan orthography is systematic and largely phonologically based. [134] Standardization of Catalan was among the topics discussed during the First International Congress of the Catalan Language, held in Barcelona October 1906. Subsequently, the Philological Section of the Institut d'Estudis Catalans (IEC, founded in 1911) published the Normes ortogràfiques in 1913 under the direction of Antoni Maria Alcover and Pompeu Fabra. In 1932, Valencian writers and intellectuals gathered in Castelló de la Plana to make a formal adoption of the so-called Normes de Castelló, a set of guidelines following Pompeu Fabra's Catalan language norms. [135]

| Pronunciation | Examples [136] | |

|---|---|---|

| ç | /s/ | feliç [fəˈlis] ("happy") |

| gu | /ɡ/ ([ɡ~ɣ]) before i and e | guerra [ˈɡɛrə] ("war") |

| /ɡw/ elsewhere | guant [ˈɡwan] ("glove") | |

| ig | [tʃ] in final position | raig [ˈratʃ] ("trickle") |

| ix | /ʃ/ ([jʃ] in some dialects) | caixa [ˈkaʃə] ("box") |

| ll | /ʎ/ | lloc [ʎɔk] ("place") |

| l·l | Normatively /l:/, but usually /l/ | novel·la [nuˈβɛlə] ("novel") |

| ny | /ɲ/ | Catalunya [kətəˈɫuɲə] (" Catalonia") |

| qu | /k/ before i and e | qui [ˈki] ("who") |

| /kw/ before other vowels | quatre [ˈkwatrə] ("four") | |

| ss | /s/ Intervocalic s is pronounced /z/ |

grossa [ˈɡɾɔsə] ("big-feminine)" casa [ˈkazə] ("house") |

| tg, tj | [ddʒ] | fetge [ˈfeddʒə] ("liver"), mitjó [midˈdʒo] ("sock") |

| tx | [tʃ] | despatx [dəsˈpatʃ] ("office") |

| tz | [ddz] | dotze [ˈdoddzə] ("twelve") |

| Notes | Examples [136] | |

|---|---|---|

| c | /s/ before i and e corresponds to ç in other contexts |

feliç ("happy-masculine-singular") - felices ("happy-feminine-plural") caço ("I hunt") - caces ("you hunt") |

| g | /ʒ/ before e and i corresponds to j in other positions |

envejar ("to envy") - envegen ("they envy") |

| final g + stressed i, and final ig before other vowels, are pronounced [tʃ] corresponds to j~g or tj~tg in other positions |

boig ['bɔtʃ] ("mad-masculine") - boja ['bɔʒə] ("mad-feminine") -boges ['bɔʒəs] ("mad-feminine plural") desig [də'zitʃ] ("wish") - desitjar ("to wish") - desitgem ("we wish") | |

| gu | /ɡ/ before e and i corresponds to g in other positions |

botiga ("shop") - botigues ("shops") |

| gü | /ɡw/ before e and i corresponds to gu in other positions |

llengua ("language") - llengües ("languages") |

| qu | /k/ before e and i corresponds to c in other positions |

vaca ("cow") - vaques ("cows") |

| qü | /kw/ before e and i corresponds to qu in other positions |

obliqua ("oblique-feminine") - obliqües ("oblique-feminine plural") |

| x | [ʃ~tʃ] initially and in onsets after a consonant [ʃ] after i otherwise, [ɡz] before stress, [ks] after |

xarxa [ˈʃarʃə] ("net") guix [ˈɡiʃ] ("chalk") exacte [əɡˈzaktə] ("exact"), fax [ˈfaks] ("fax") |

Grammar

The grammar of Catalan is similar to other Romance languages. Features include: [137]

- Use of definite and indefinite articles. [137]

- Nouns, adjectives, pronouns, and articles are inflected for gender (masculine and feminine), and number (singular and plural). There is no case inflexion, except in pronouns. [137]

- Verbs are highly inflected for person, number, tense, aspect, and mood (including a subjunctive). [137]

- There are no modal auxiliaries. [137]

- Word order is freer than in English. [137]

Gender and number inflection

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In gender inflection, the most notable feature is (compared to Portuguese, Spanish or Italian), the loss of the typical masculine suffix -o. Thus, the alternance of -o/-a, has been replaced by ø/-a. [86] There are only a few exceptions, like minso/minsa ("scarce"). [86] Many not completely predictable morphological alternations may occur, such as: [86]

- Affrication: boig/boja ("insane") vs. lleig/lletja ("ugly")

- Loss of n: pla/plana ("flat") vs. segon/segona ("second")

- Final obstruent devoicing: sentit/sentida ("felt") vs. dit/dita ("said")

Catalan has few suppletive couplets, like Italian and Spanish, and unlike French. Thus, Catalan has noi/noia ("boy"/"girl") and gall/gallina ("cock"/"hen"), whereas French has garçon/fille and coq/poule. [86]

There is a tendency to abandon traditionally gender-invariable adjectives in favor of marked ones, something prevalent in Occitan and French. Thus, one can find bullent/bullenta ("boiling") in contrast with traditional bullent/bullent. [86]

As in the other Western Romance languages, the main plural expression is the suffix -s, which may create morphological alternations similar to the ones found in gender inflection, albeit more rarely. [86] The most important one is the addition of -o- before certain consonant groups, a phonetic phenomenon that does not affect feminine forms: el pols/els polsos ("the pulse"/"the pulses") vs. la pols/les pols ("the dust"/"the dusts"). [138]

Determiners

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The inflection of determinatives is complex, specially because of the high number of elisions, but is similar to the neighboring languages. [133] Catalan has more contractions of preposition + article than Spanish, like dels ("of + the [plural]"), but not as many as Italian (which has sul, col, nel, etc.). [133]

Central Catalan has abandoned almost completely unstressed possessives (mon, etc.) in favor of constructions of article + stressed forms (el meu, etc.), a feature shared with Italian. [133]

Personal pronouns

| singular | plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | jo, mi | nosaltres | |

| 2nd person | informal | tu | vosaltres |

| formal | vostè | vostès | |

| respectful | (vós) [141] | ||

| 3rd person | masculine | ell | ells |

| feminine | ella | elles | |

The morphology of Catalan personal pronouns is complex, especially in unstressed forms, which are numerous (13 distinct forms, compared to 11 in Spanish or 9 in Italian). [133] Features include the gender-neutral ho and the great degree of freedom when combining different unstressed pronouns (65 combinations). [133]

Catalan pronouns exhibit T–V distinction, like all other Romance languages (and most European languages, but not Modern English). This feature implies the use of a different set of second person pronouns for formality.

This flexibility allows Catalan to use extraposition extensively, much more than French or Spanish. Thus, Catalan can have m'hi recomanaren ("they recommended me to him"), whereas in French one must say ils m'ont recommandé à lui, and Spanish me recomendaron a él. [133] This allows the placement of almost any nominal term as a sentence topic, without having to use so often the passive voice (as in French or English), or identifying the direct object with a preposition (as in Spanish). [133]

Verbs

| Non-finite | Form | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infinitive | portar | |||||

| Gerund | portant | |||||

| Past participle | portat (portat, portada, portats, portades) | |||||

| Indicative | jo | tu | ell / ella vostè |

nosaltres | vosaltres vós |

ells / elles vostès] |

| Present | porto | portes | porta | portem | porteu | porten |

| Imperfect | portava | portaves | portava | portàvem | portàveu | portaven |

| Preterite (archaic) | portí | portares | portà | portàrem | portàreu | portaren |

| Future | portaré | portaràs | portarà | portarem | portareu | portaran |

| Conditional | portaria | portaries | portaria | portaríem | portaríeu | portarien |

| Subjunctive | jo | tu | ell / ella vostè |

nosaltres | vosaltres vós |

ells / elles vostès] |

| Present | porti | portis | porti | portem | porteu | portin |

| Imperfect | portés | portéssis | portés | portéssim | portéssiu | portessin |

| Imperative | jo | tu | ell / ella vostè |

nosaltres | vosaltres vós |

ells / elles vostès] |

| — | — | porta | porti | portem | porteu | portin |

Like all the Romance languages, Catalan verbal inflection is more complex than the nominal. Suffixation is omnipresent, whereas morphological alternations play a secondary role. [133] Vowel alternances are active, as well as infixation and suppletion. However, these are not as productive as in Spanish, and are mostly restricted to irregular verbs. [133]

The Catalan verbal system is basically common to all Western Romance, except that most dialects have replaced the synthetic indicative perfect with a periphrastic form of anar ("to go") + infinitive. [133]

Catalan verbs are traditionally divided into three conjugations, with vowel themes -a-, -e-, -i-, the last two being split into two subtypes. However, this division is mostly theoretical. [133] Only the first conjugation is nowadays productive (with about 3500 common verbs), whereas the third (the subtype of servir, with about 700 common verbs) is semiproductive. The verbs of the second conjugation are fewer than 100, and it is not possible to create new ones, except by compounding. [133]

Syntax

The grammar of Catalan follows the general pattern of Western Romance languages. The primary word order is subject–verb–object. [143] However, word order is very flexible. Commonly, verb-subject constructions are used to achieve a semantic effect. The sentence "The train has arrived" could be translated as Ha arribat el tren or El tren ha arribat. Both sentences mean "the train has arrived", but the former puts a focus on the train, while the latter puts a focus on the arrival. This subtle distinction is described as "what you might say while waiting in the station" versus "what you might say on the train." [144]

Catalan names

In Spain, every person officially has two surnames, one of which is the father's first surname and the other is the mother's first surname. [145] The law contemplates the possibility of joining both surnames with the Catalan conjunction i ("and"). [145] [146]

Sample text

Selected text [147] from Manuel de Pedrolo's 1970 novel Un amor fora ciutat ("A love affair outside the city").

| Original | Word-for-word translation [147] | Free translation |

|---|---|---|

| Tenia prop de divuit anys quan vaig conèixer | I was having close to eighteen years, when I go [past auxiliary] know (=I met) | I was about eighteen years old when I met |

| en Raül, a l'estació de Manresa. | the Raül, at the station of (=in) Manresa. | Raül, at Manresa railway station. |

| El meu pare havia mort, inesperadament i encara jove, | The my father had died, unexpectedly and still young, | My father had died, unexpectedly and still young, |

| un parell d'anys abans, i d'aquells temps | a couple of years before, and of those times | a couple of years before; and from that time |

| conservo un record de punyent solitud. | I keep a memory of acute loneliness | I still harbor memories of great loneliness. |

| Les meves relacions amb la mare | The my relations with the mother | My relationship with my mother |

| no havien pas millorat, tot el contrari, | not had at all improved, all the contrary, | had not improved; quite the contrary, |

| potser fins i tot empitjoraven | perhaps even they were worsening | and arguably it was getting even worse |

| a mesura que em feia gran. | at step that (=in proportion as) myself I was making big (=I was growing up). | as I grew up. |

| No existia, no existí mai entre nosaltres, | Not it was existing, not it existed never between us, | There did not exist, at no point had there ever existed between us |

| una comunitat d'interessos, d'afeccions. | a community of interests, of affections. | shared interests or affection. |

| Cal creure que cercava... una persona | It is necessary to believe that I was seeking... a person | I guess I was seeking... a person |

| en qui centrar la meva vida afectiva. | in whom to center the my life affective. | in whom I could center my emotional life. |

See also

- Organizations

- Institut d'Estudis Catalans (Catalan Studies Institute)

- Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua (Valencian Academy of the Language)

- Òmnium Cultural

- Plataforma per la Llengua

- Scholars

- Other

Notes

- ^ The Valencian Normative Dictionary of the Valencian Academy of the Language states that Valencian is a "Romance language spoken in the Valencian Community, as well as in Catalonia, the Balearic Islands, the French department of the Pyrénées-Orientales, the Principality of Andorra, the eastern flank of Aragon and the Sardinian town of Alghero (unique in Italy), where it receives the name of 'Catalan'."

- ^ The Catalan Language Dictionary of the Institut d'Estudis Catalans states in the sixth definition of "Valencian" that, in the Valencian Community, it is equivalent to Catalan language.

- ^ a b Some Iberian scholars may alternatively classify Catalan as Iberian Romance.

- ^ Although in business and daily life other languages are common, and due to immigration Catalan mother-tongue speakers are only 35.7% of the population. See Languages of Andorra.

References

- ^

a

b

c

d

e

Catalan at

Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- ^ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian (24 May 2022). "Glottolog 4.8 - Shifted Western Romance". Glottolog. Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Archived from the original on 27 November 2023. Retrieved 11 November 2023.

- ^ "World Atlas of Languages: Standard Catalan". en.wal.unesco.org. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ "Definition of CATALAN". 16 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Definition of Catalan | Dictionary.com". www.dictionary.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Wheeler 2010, p. 191.

- ^ Minder, Raphael (21 November 2016). "Italy's Last Bastion of Catalan Language Struggles to Keep It Alive". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ "els Països Catalans". enciclopèdia.cat (in Catalan). Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- ^ a b c Wheeler 2010, pp. 190–191.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Costa Carreras & Yates 2009, pp. 6–7.

- ^ García Venero 2006.

- ^ Burke 1900, p. 154.

- ^ "Definition of CATALAN". 16 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua (9 February 2005). "Acord de l'Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua (AVL), adoptat en la reunió plenària del 9 de febrer del 2005, pel qual s'aprova el dictamen sobre els principis i criteris per a la defensa de la denominació i l'entitat del valencià" (PDF) (in Valencian). p. 52. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ Lledó 2011, pp. 334–337.

- ^ Veny 1997, pp. 9–18.

- ^ a b c Moran 2004, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Riquer 1964.

- ^ a b c d Wheeler 2010, p. 190.

- ^ Trobes en llaors de la Verge Maria ("Poems of praise of the Virgin Mary") 1474.

- ^ Sales Vives, Pere (22 September 2020). L'Espanyolització de Mallorca: 1808–1932 (in Catalan). El Gall editor. p. 422. ISBN 9788416416707.

- ^ Antoni Simon, Els orígens històrics de l'anticatalanisme, páginas 45-46, L'Espill, nº 24, Universitat de València

- ^ Mayans Balcells, Pere (2019). Cròniques Negres del Català A L'Escola (in Catalan) (del 1979 ed.). Edicions del 1979. p. 230. ISBN 978-84-947201-4-7.

- ^ Lluís, García Sevilla (2021). Recopilació d'accions genocides contra la nació catalana (in Catalan). Base. p. 300. ISBN 9788418434983.

- ^ Bea Seguí, Ignaci (2013). En cristiano! Policia i Guàrdia Civil contra la llengua catalana (in Catalan). Cossetània. p. 216. ISBN 9788490341339.

- ^ "Enllaç al Manifest Galeusca on en l'article 3 es denuncia l'asimetria entre el castellà i les altres llengües de l'Estat Espanyol, inclosa el català". Archived from the original on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- ^ Radatz, Hans-Ingo (8 October 2020). "Spain in the 19th century: Spanish Nation Building and Catalonia's attempt at becoming an Iberian Prussia". ResearchGate.

- ^ a b de la Cierva, Ricardo (1981). Historia general de España: Llegada y apogeo de los Borbones (in Catalan). Planeta. p. 78. ISBN 8485753003.

- ^ "L'interdiction de la langue catalane en Roussillon par Louis XIV" (PDF). "CRDP, Académie de Montpellier. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 December 2010.

- ^ Àngela-Rosa Menages, Joan-Lluís Monjo. "El patuet valencià, un reflex lingüístic de la societat algeriana colonial (1830–1962)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2013.

- ^ Plataforma per la llengua. "The Catalan Language" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 March 2022.

- ^ Marfany, Marta; Simó, Marta Marfany (2002). Els menorquins d'Algèria (in Catalan). L'Abadia de Montserrat. ISBN 978-84-8415-366-5.

- ^ Marfany 2002.

- ^ "Charte en faveur du Catalan". Archived from the original on 22 December 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2010. "La catalanitat a la Catalunya Nord". Archived from the original on 9 March 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ Merle, René (5 January 2010). Visions de "l'idiome natal" à travers l'enquête impériale sur les patois 1807–1812 (in French). Perpinyà: Editorial Trabucaire. p. 223. ISBN 978-2849741078.

- ^ Costa Carreras & Yates 2009, pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Wheeler 2005, p. 1.

- ^ Burgen, Stephen (22 November 2012). "Catalan: a language that has survived against the odds". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ Manent, Albert; Crexell, Joan (1988). Bibliografia catalana dels anys més difícils (1939-1943). Barcelona: Publicacions de l'Abadia de Montserrat, S.A. p. 14. ISBN 8472029379.

- ^ CORNELLÀ-DETRELL, JORDI (2011). Literature as a Response to Cultural and Political Repression in Franco's Catalonia. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1-85566-201-8. JSTOR 10.7722/j.cttn346z.

- ^ "Una polèmica literària sota el franquisme". Palavracomum (in Catalan). 20 July 2015.

- ^ "Primera emisión de un programa en catalán". RTVE (in European Spanish). 30 July 2018.

- ^ Casademont, Enric Pujol (2020). "Culture, language and politics. The Catalan cultural resistance during the Franco regime (1939–1977)" (PDF). Catalan Historical Review. 13: 69–84. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Rendon, Sílvio (2007). "The Catalan premium: language and employment in Catalonia". Journal of Population Economics. 20 (3): 669–686. doi: 10.1007/s00148-005-0048-5. hdl: 10016/291. ISSN 0933-1433. JSTOR 20730773. S2CID 29009762.

- ^ Katrin Voltmer (2006). Mass Media and Political Communication in New Democracies. Psychology Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-415-33779-3.

- ^ a b c d e Wheeler 2003, p. 207.

- ^ Armora, Esther (9 September 2013). "Cataluña ordena incumplir las sentencias sobre el castellano en las escuelas" [Catalonia orders violate the judgments on the Castilian in schools]. ABC (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ^ Wong, Alia (3 November 2017). "Is Catalonia Using Schools as a Political Weapon?". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 3 November 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ^ "You are here: ANSAmed. Catalonia: Supreme Court, 25% of lessons must be in Spanish". 21 January 2022. Archived from the original on 22 January 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ "Idescat. Annual indicators. Language uses. First language, language of identification and habitual language. Results". Institut d'Estadística de Catalunya.

- ^ "Idescat. Demographics and quality of life. Language uses. First language, language of identification and habitual language. 2003. Results". Institut d'Estadística de Catalunya. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ "2010 Language Policy Report". Generalitat de Catalunya. Archived from the original on 15 April 2014.

- ^ CPNL, Consorci per a la Normalització Lingüística-. "Consorci per a la Normalització Lingüística". Consorci per a la Normalització Lingüística – CPNL.

- ^ "Catalan language resources | Joshua Project". joshuaproject.net. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ Philip D. Rasico. "La llengua dels mallorquins de San Pedro (Argentina)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020.

- ^ "COMUNITATS CATALANES A L'EXTERIOR – index". catalansalmon.com. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ Friend, Julius W. (2012). Stateless Nations: Western European Regional Nationalisms and the Old Nations. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-230-36179-9. Retrieved 5 March 2016.[ permanent dead link]

- ^ Smith, Nathaniel B.; Bergin, Thomas Goddard (1984). An Old Provençal Primer. New York: Garland. p. 9. ISBN 0-8240-9030-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Enciclopèdia Catalana, p. 632.

- ^ a b c d e Feldhausen 2010, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e Schlösser 2005, p. 60f.

- ^ Ross, Marc Howard (2007). Cultural Contestation in Ethnic Conflict. Cambridge University Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-139-46307-2.

- ^ a b Jud 1925.

- ^ a b Colón 1993, pp. 33–35.

- ^ a b c d e Moll 2006, p. 47.

- ^ a b Portuguese and Spanish have estiagem and estiaje, respectively, for drought, dry season or low water levels.

- ^ a b Portuguese and Spanish have véspera and víspera, respectively, for eve, or the day before.

- ^ Spanish also has trozo, and it is actually a borrowing from Catalan tros. Colón 1993, p 39. Portuguese has troço, but aside from also being a loanword, it has a very different meaning: "thing", "gadget", "tool", "paraphernalia".

- ^ Modern Spanish also has gris, but it is a modern borrowing from Occitan. The original word was pardo, which stands for "reddish, yellow-orange, medium-dark and of moderate to weak saturation. It also can mean ochre, pale ochre, dark ohre, brownish, tan, greyish, grey, desaturated, dirty, dark, or opaque." Gallego, Rosa; Sanz, Juan Carlos (2001). Diccionario Akal del color (in Spanish). Akal. ISBN 978-84-460-1083-8.

- ^ A 20th century introduction from French.

- ^ Colón 1993, p. 55.

- ^ Bruguera 2008, p. 3046.

- ^ "Sociolinguistic situation in Catalan-speaking areas. Tables. Official data about the sociolinguistic situation in Catalan-speaking areas: Catalonia (2003), Andorra (2004), the Balearic Islands (2004), Aragonese Border (2004), Northern Catalonia (2004), Alghero (2004) and Valencian Community (2004)". Generalitat of Catalonia. 7 August 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- ^ Catalan, language of Europe (PDF), Generalitat of Catalonia, archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2012, retrieved 13 March 2012

- ^ Población según lengua habitual. Datos comparados 2003–2008. Cataluña. Año 2008, Encuesta de Usos Lingüísticos de la población (2003 y 2008), Instituto de Estadística de Cataluña

- ^ Informe sobre la situació de la llengua catalana [Report on the situation of the Catalan language] (PDF) (in Catalan), Xarxa CRUSCAT, 2011, archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2013

- ^ Geli, Carles (8 July 2019). "El uso del catalán crece: lo entiende el 94,4% y lo habla el 81,2%". El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Departament d'Estadística. Ajuntament de Barcelona (2011). "Coneixement del català: Evolució de les característiques de la població de Barcelona (Knowledge of Catalan in Barcelona)". Ajuntament de Barcelona (in Catalan). Archived from the original on 31 December 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- ^ "Coneixement del català: Evolució de les característiques de la població de Barcelona (Knowledge of Catalan in Barcelona)". Ajuntament de Barcelona (in Catalan). 2011. Archived from the original on 31 December 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- ^

a

b Sources:

- Catalonia: Statistic data of 2001 census, from Institut d'Estadística de Catalunya, Generalitat de Catalunya [1].

- Land of Valencia: Statistical data from 2001 census, from Institut Valencià d'Estadística, Generalitat Valenciana "Població" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2005. Retrieved 23 June 2005..

- Land of Valencia: Statistical data from 2001 census, from Institut Valencià d'Estadística, Generalitat Valenciana [2] Archived 16 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- Balearic Islands: Statistical data from 2001 census, from Institut Balear d'Estadística, Govern de les Illes Balears [3] Archived 1 January 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- Northern Catalonia: Media Pluriel Survey commissioned by Prefecture of Languedoc-Roussillon Region done in October 1997 and published in January 1998 "Information_catalan". Archived from the original on 14 April 2005. Retrieved 23 June 2005..

- Andorra: Sociolinguistic data from Andorran Government, 1999.

- Aragon: Sociolinguistic data from Euromosaic [4].

- Alguer: Sociolinguistic data from Euromosaic [5].

- Rest of World: Estimate for 1999 by the Federació d'Entitats Catalanes outside the Catalan Countries.

- ^ Martínez, D. (26 November 2011). "Una isla valenciana en Murcia" [A Valencian island in Murcia]. ABC (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ^ "Enquesta d'usos lingüístics de la població. 2018" [Survey of the linguistic usage of the population. 2018]. IDESCAT/Generalitat de Catalunya (in Catalan). 2019.

- ^ Red Cruscat del Instituto de Estudios Catalanes

- ^ "Tv3 – Telediario: La salud del catalán – YouTube". YouTube. Archived from the original on 16 May 2015.

- ^ "El català no avança en la incorporació de nous parlants" [Catalan is not progressing in the incorporation of new speakers]. Telenotícies (in Catalan). 23 October 2007. Archived from the original on 24 November 2007.